Quadratic formula

In elementary algebra, the quadratic formula is a formula that provides the solution(s) to a quadratic equation. There are other ways of solving a quadratic equation instead of using the quadratic formula, such as factoring (direct factoring, grouping, AC method), completing the square, graphing and others.[1]

Given a general quadratic equation of the form

with x representing an unknown, a, b and c representing constants with a ≠ 0, the quadratic formula is:

where the plus-minus symbol "±" indicates that the quadratic equation has two solutions.[2] Written separately, they become:

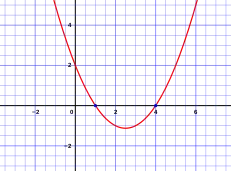

Each of these two solutions is also called a root (or zero) of the quadratic equation. Geometrically, these roots represent the x-values at which any parabola, explicitly given as y = ax2 + bx + c, crosses the x-axis.[3]

As well as being a formula that yields the zeros of any parabola, the quadratic formula can also be used to identify the axis of symmetry of the parabola,[4] and the number of real zeros the quadratic equation contains.[5]

Equivalent formulations

The quadratic formula may also be written as:

which may be simplified to:

This version of the formula is convenient when complex roots are involved, in which case the expression outside the square root will be the real part—and the square root expression the imaginary part. The expression inside the square root is a discriminant. The complex expression will be:

Muller's method

A lesser known quadratic formula, which is used in Muller's method and which can be found from Vieta's formulas, provides the same roots via the equation:

Formulations based on alternative parametrizations

The standard parametrization of the quadratic equation is

Some sources, particularly older ones, use alternative parameterizations of the quadratic equation such as

- , where ,[6]

or

- , where .[7]

These alternative parametrizations result in slightly different forms for the solution, but which are otherwise equivalent to the standard parametrization.

Derivations of the formula

Many different methods to derive the quadratic formula are available in the literature. The standard one is a simple application of the completing the square technique.[8][9][10][11] Alternative methods are sometimes simpler than completing the square, and may offer interesting insight into other areas of mathematics.

Standard method

Divide the quadratic equation by , which is allowed because is non-zero:

Subtract c/a from both sides of the equation, yielding:

The quadratic equation is now in a form to which the method of completing the square is applicable. In fact, by adding a constant to both sides of the equation such that the left hand side becomes a complete square, the quadratic equation becomes:

which produces:

Accordingly, after rearranging the terms on the right hand side to have a common denominator, we obtain:

The square has thus been completed. Taking the square root of both sides yields the following equation:

In which case, isolating the would give the quadratic formula:

There are many alternatives of this derivation with minor differences, mostly concerning the manipulation of .

Method 2

The majority of algebra texts published over the last several decades teach completing the square using the sequence presented earlier:

- Divide each side by to make the polynomial monic.

- Rearrange.

- Add to both sides to complete the square.

- Rearrange the terms in the right side to have a common denominator.

- Take the square root of both sides.

- Isolate .

Completing the square can also be accomplished by a sometimes shorter and simpler sequence:[12]

- Multiply each side by ,

- Rearrange.

- Add to both sides to complete the square.

- Take the square root of both sides.

- Isolate .

In which case, the quadratic formula can also be derived as follows:

This derivation of the quadratic formula is ancient and was known in India at least as far back as 1025.[13] Compared with the derivation in standard usage, this alternate derivation avoids fractions and squared fractions until the last step and hence does not require a rearrangement after step 3 to obtain a common denominator in the right side.[12]

Method 3

Similar to Method 1, divide each side by to make left-hand-side polynomial monic (i.e., the coefficient of becomes 1).

Write the equation in a more compact and easier-to-handle format:

where and .

Complete the square by adding to the first two terms and subtracting it from the third term:

Rearrange the left side into a difference of two squares:

and factor it:

which implies that either

or

Each of these two equations is linear and can be solved for , obtaining:

or

By re-expressing and back into and , respectively, the quadratic formula can then be obtained.

By substitution

Another technique is solution by substitution.[14] In this technique, we substitute into the quadratic to get:

Expanding the result and then collecting the powers of produces:

We have not yet imposed a second condition on and , so we now choose so that the middle term vanishes. That is, or . Subtracting the constant term from both sides of the equation (to move it to the right hand side) and then dividing by gives:

Substituting for gives:

Therefore,

By re-expressing in terms of using the formula , the usual quadratic formula can then be obtained:

By using algebraic identities

The following method was used by many historical mathematicians:[15]

Let the roots of the standard quadratic equation be r1 and r2. The derivation starts by recalling the identity:

Taking the square root on both sides, we get:

Since the coefficient a ≠ 0, we can divide the standard equation by a to obtain a quadratic polynomial having the same roots. Namely,

From this we can see that the sum of the roots of the standard quadratic equation is given by −b/a, and the product of those roots is given by c/a. Hence the identity can be rewritten as:

Now,

Since r2 = −r1 − b/a, if we take

then we obtain

and if we instead take

then we calculate that

Combining these results by using the standard shorthand ±, we have that the solutions of the quadratic equation are given by:

By Lagrange resolvents

An alternative way of deriving the quadratic formula is via the method of Lagrange resolvents,[16] which is an early part of Galois theory.[17] This method can be generalized to give the roots of cubic polynomials and quartic polynomials, and leads to Galois theory, which allows one to understand the solution of algebraic equations of any degree in terms of the symmetry group of their roots, the Galois group.

This approach focuses on the roots more than on rearranging the original equation. Given a monic quadratic polynomial

assume that it factors as

Expanding yields

where p = −(α + β) and q = αβ.

Since the order of multiplication does not matter, one can switch α and β and the values of p and q will not change: one can say that p and q are symmetric polynomials in α and β. In fact, they are the elementary symmetric polynomials – any symmetric polynomial in α and β can be expressed in terms of α + β and αβ The Galois theory approach to analyzing and solving polynomials is: given the coefficients of a polynomial, which are symmetric functions in the roots, can one "break the symmetry" and recover the roots? Thus solving a polynomial of degree n is related to the ways of rearranging ("permuting") n terms, which is called the symmetric group on n letters, and denoted Sn. For the quadratic polynomial, the only way to rearrange two terms is to swap them ("transpose" them), and thus solving a quadratic polynomial is simple.

To find the roots α and β, consider their sum and difference:

These are called the Lagrange resolvents of the polynomial; notice that one of these depends on the order of the roots, which is the key point. One can recover the roots from the resolvents by inverting the above equations:

Thus, solving for the resolvents gives the original roots.

Now r1 = α + β is a symmetric function in α and β, so it can be expressed in terms of p and q, and in fact r1 = −p as noted above. But r2 = α − β is not symmetric, since switching α and β yields −r2 = β − α (formally, this is termed a group action of the symmetric group of the roots). Since r2 is not symmetric, it cannot be expressed in terms of the coefficients p and q, as these are symmetric in the roots and thus so is any polynomial expression involving them. Changing the order of the roots only changes r2 by a factor of −1, and thus the square r22 = (α − β)2 is symmetric in the roots, and thus expressible in terms of p and q. Using the equation

yields

and thus

If one takes the positive root, breaking symmetry, one obtains:

and thus

Thus the roots are

which is the quadratic formula. Substituting p = b/a, q = c/a yields the usual form for when a quadratic is not monic. The resolvents can be recognized as r1/2 = −p/2 = −b/2a being the vertex, and r22 = p2 − 4q is the discriminant (of a monic polynomial).

A similar but more complicated method works for cubic equations, where one has three resolvents and a quadratic equation (the "resolving polynomial") relating r2 and r3, which one can solve by the quadratic equation, and similarly for a quartic equation (degree 4), whose resolving polynomial is a cubic, which can in turn be solved.[16] The same method for a quintic equation yields a polynomial of degree 24, which does not simplify the problem, and, in fact, solutions to quintic equations in general cannot be expressed using only roots.

Historical development

The earliest methods for solving quadratic equations were geometric. Babylonian cuneiform tablets contain problems reducible to solving quadratic equations.[18] The Egyptian Berlin Papyrus, dating back to the Middle Kingdom (2050 BC to 1650 BC), contains the solution to a two-term quadratic equation.[19]

The Greek mathematician Euclid (circa 300 BC) used geometric methods to solve quadratic equations in Book 2 of his Elements, an influential mathematical treatise.[20] Rules for quadratic equations appear in the Chinese The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art circa 200 BC.[21][22] In his work Arithmetica, the Greek mathematician Diophantus (circa 250 AD) solved quadratic equations with a method more recognizably algebraic than the geometric algebra of Euclid.[20] His solution gives only one root, even when both roots are positive.[23]

The Indian mathematician Brahmagupta (597–668 AD) explicitly described the quadratic formula in his treatise Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta published in 628 AD,[24] but written in words instead of symbols.[25] His solution of the quadratic equation ax2 + bx = c was as follows: "To the absolute number multiplied by four times the [coefficient of the] square, add the square of the [coefficient of the] middle term; the square root of the same, less the [coefficient of the] middle term, being divided by twice the [coefficient of the] square is the value."[26] This is equivalent to:

The 9th-century Persian mathematician Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī solved quadratic equations algebraically.[27] The quadratic formula covering all cases was first obtained by Simon Stevin in 1594.[28] In 1637 René Descartes published La Géométrie containing special cases of the quadratic formula in the form we know today.[29]

Significant uses

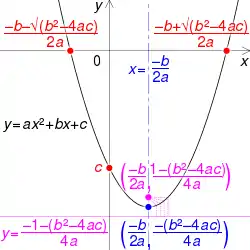

Geometric significance

- Roots and y-intercept in red

- Vertex and axis of symmetry in blue

- Focus and directrix in pink

In terms of coordinate geometry, a parabola is a curve whose (x, y)-coordinates are described by a second-degree polynomial, i.e. any equation of the form:

where p represents the polynomial of degree 2 and a0, a1, and a2 ≠ 0 are constant coefficients whose subscripts correspond to their respective term's degree. The geometrical interpretation of the quadratic formula is that it defines the points on the x-axis where the parabola will cross the axis. Additionally, if the quadratic formula was looked at as two terms,

the axis of symmetry appears as the line x = −b/2a. The other term, √b2 − 4ac/2a, gives the distance the zeros are away from the axis of symmetry, where the plus sign represents the distance to the right, and the minus sign represents the distance to the left.

If this distance term were to decrease to zero, the value of the axis of symmetry would be the x value of the only zero, that is, there is only one possible solution to the quadratic equation. Algebraically, this means that √b2 − 4ac = 0, or simply b2 − 4ac = 0 (where the left-hand side is referred to as the discriminant). This is one of three cases, where the discriminant indicates how many zeros the parabola will have. If the discriminant is positive, the distance would be non-zero, and there will be two solutions. However, there is also the case where the discriminant is less than zero, and this indicates the distance will be imaginary – or some multiple of the complex unit i, where i = √−1 – and the parabola's zeros will be complex numbers. The complex roots will be complex conjugates, where the real part of the complex roots will be the value of the axis of symmetry. There will be no real values of x where the parabola crosses the x-axis.

Dimensional analysis

If the constants a, b, and/or c are not unitless, then the units of x must be equal to the units of b/a, due to the requirement that ax2 and bx agree on their units. Furthermore, by the same logic, the units of c must be equal to the units of b2/a, which can be verified without solving for x. This can be a powerful tool for verifying that a quadratic expression of physical quantities has been set up correctly, prior to solving this.

References

- "Quadratic Factorisation: The Complete Guide". Math Vault. 2016-03-13. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Sterling, Mary Jane (2010), Algebra I For Dummies, Wiley Publishing, p. 219, ISBN 978-0-470-55964-2

- "Understanding the quadratic formula". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "Axis of Symmetry of a Parabola. How to find axis from equation or from a graph. To find the axis of symmetry ..." www.mathwarehouse.com. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "Discriminant review". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Kahan, Willian (November 20, 2004), On the Cost of Floating-Point Computation Without Extra-Precise Arithmetic (PDF), retrieved 2012-12-25

- "Quadratic Formula", Proof Wiki, retrieved 2016-10-08

- Rich, Barnett; Schmidt, Philip (2004), Schaum's Outline of Theory and Problems of Elementary Algebra, The McGraw–Hill Companies, ISBN 0-07-141083-X, Chapter 13 §4.4, p. 291

- Li, Xuhui. An Investigation of Secondary School Algebra Teachers' Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching Algebraic Equation Solving, p. 56 (ProQuest, 2007): "The quadratic formula is the most general method for solving quadratic equations and is derived from another general method: completing the square."

- Rockswold, Gary. College algebra and trigonometry and precalculus, p. 178 (Addison Wesley, 2002).

- Beckenbach, Edwin et al. Modern college algebra and trigonometry, p. 81 (Wadsworth Pub. Co., 1986).

- Hoehn, Larry (1975). "A More Elegant Method of Deriving the Quadratic Formula". The Mathematics Teacher. 68 (5): 442–443. doi:10.5951/MT.68.5.0442.

- Smith, David E. (1958). History of Mathematics, Vol. II. Dover Publications. p. 446. ISBN 0486204308.

- Joseph J. Rotman. (2010). Advanced modern algebra (Vol. 114). American Mathematical Soc. Section 1.1

- Debnath, Lokenath (2009). "The legacy of Leonhard Euler – a tricentennial tribute". International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 40 (3): 353–388. doi:10.1080/00207390802642237. S2CID 123048345.

- Clark, A. (1984). Elements of abstract algebra. Courier Corporation. p. 146.

- Prasolov, Viktor; Solovyev, Yuri (1997), Elliptic functions and elliptic integrals, AMS Bookstore, ISBN 978-0-8218-0587-9, §6.2, p. 134

- Irving, Ron (2013). Beyond the Quadratic Formula. MAA. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-88385-783-0.

- The Cambridge Ancient History Part 2 Early History of the Middle East. Cambridge University Press. 1971. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-521-07791-0.

- Irving, Ron (2013). Beyond the Quadratic Formula. MAA. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-88385-783-0.

- Aitken, Wayne. "A Chinese Classic: The Nine Chapters" (PDF). Mathematics Department, California State University. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- Smith, David Eugene (1958). History of Mathematics. Courier Dover Publications. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-486-20430-7.

- Smith, David Eugene (1958). History of Mathematics. Courier Dover Publications. p. 134. ISBN 0-486-20429-4.

- Bradley, Michael. The Birth of Mathematics: Ancient Times to 1300, p. 86 (Infobase Publishing 2006).

- Mackenzie, Dana. The Universe in Zero Words: The Story of Mathematics as Told through Equations, p. 61 (Princeton University Press, 2012).

- Stillwell, John (2004). Mathematics and Its History (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 87. ISBN 0-387-95336-1.

- Irving, Ron (2013). Beyond the Quadratic Formula. MAA. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-88385-783-0.

- Struik, D. J.; Stevin, Simon (1958), The Principal Works of Simon Stevin, Mathematics (PDF), II–B, C. V. Swets & Zeitlinger, p. 470

- Rene Descartes. The Geometry.