REGN-EB3

REGN-EB3 is an experimental biopharmaceutical treatment comprising three monoclonal antibodies under development by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals to treat Ebola virus disease. In August 2019, Congolese health officials announced that REGN-EB3 and a similar monoclonal antibody treatment, mAb114, were more effective than two other treatments being used at the time.

Chemistry

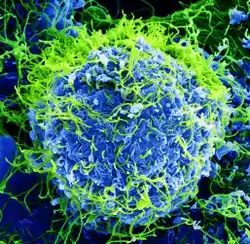

REGN-EB3 is a cocktail of three monoclonal antibodies, REGN3470, 3471, and 3479. It was invented by Regeneron using its VelociSuite technologies.[1] Using three antibodies targets the Ebola virus at multiple points since the virus is known to mutate in different outbreaks.[2]

Mechanism of action

Monoclonal antibodies are antibodies that are made by identical immune cells that are all clones of a unique parent cell. Monoclonal antibodies can have monovalent affinity, in that they bind to the same epitope (the part of an antigen that is recognized by the antibody).

Development

The 2014 Ebola outbreak killed more than 11,300 people. Regeneron used its VelociGene, VelocImmune and VelociMab antibody discovery and production technologies and coordinated with the U.S. government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA).[2] The therapy was developed in six months and a Phase 1 trial in healthy humans was completed in 2015.[2]

REGN-EB3 has received orphan drug designation from both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency.[1] REGN-EB3 is being developed, tested, and manufactured as part of an agreement established in 2015 with BARDA, part of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).[1]REGN-EB3 is currently under clinical development and its safety and efficacy have not been fully evaluated by any regulatory authority.[1]It was developed against the Zaire species of Ebola virus, but the Sudan and Bundibugyo strains have also caused outbreaks and it is unlikely that EB3 would be effective against these strains.[3]

In October 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb, formerly REGN-EB3) with an indication for the treatment of infection caused by Zaire ebolavirus.[4]

Dosage

EB3 is administered in a single dose and is stable enough to not need to be stored in a deep freezer.[2]

Clinical trial in the Democratic Republic of Congo

During the 2018 Équateur province Ebola outbreak, a similar monoclonal antibody treatment, mAb114, was requested by the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) Ministry of Public Health. mAb114 was approved for compassionate use by the World Health Organization MEURI ethical protocol and at DRC ethics board. mAb114 was sent along with other therapeutic agents to the outbreak sites.[5][6][7] However, the outbreak came to a conclusion before any therapeutic agents were given to patients.[7]

Approximately one month following the conclusion of the Équateur province outbreak, a distinct outbreak was noted in Kivu in the DRC (2018–20 Kivu Ebola outbreak). Once again, mAb114 received approval for compassionate use by WHO MEURI and DRC ethic boards and has been given to many patients under these protocols.[7] In November 2018, the Pamoja Tulinde Maisha (PALM [together save lives]) open-label randomized clinical control trial was begun at multiple treatment units testing mAb114, REGN-EB3 and remdesivir to ZMapp. Despite the difficulty of running a clinical trial in a conflict zone, investigators have enrolled 681 patients towards their goal of 725.

This is the second largest outbreak with (as of January 2020) over 3,400 confirmed or probable cases, including more than 2,200 who have died.[8][9]

An interim analysis by the Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) of the first 499 patient found that mAb114 and REGN-EB3 were superior to the comparator ZMapp. Overall mortality of patients in the ZMapp and Remdesivir groups were 49% and 53% compared to 34% and 29% for mAb114 and REGN-EB3. When looking at patients who arrived early after disease symptoms appeared, survival was 89% for mAB114 and 94% for REGN-EB3. While the study was not powered to determine whether there is any difference between REGN-EB3 and mAb114, the survival difference between those two therapies and ZMapp was significant. This led to the DSMB halting the study and PALM investigators dropping the remdesivir and ZMapp arms from the clinical trial. All patients in the outbreak who elect to participate in the trial will now be given either mAb114 or REGN-EB3.[10][11][12][13]

In August 2019, Congolese health officials announced it was more effective compared to two other treatments being used at the time.[14][12][15]

Among patients treated with it, 34% died; the mortality rate improved if the drug was administered soon after infection, in a timely diagnosis – critical for those infected with diseases like Ebola that can cause sepsis and, eventually, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, more quickly than other diseases.[16] The survival rate if the drug was administered shortly after the infection was 89%.[8]

References

- "Palm Ebola Clinical Trial Stopped Early As Regeneron's REGN-EB3 Therapy Shows Superiority to ZMAPP in Preventing Ebola Deaths". Regeneron. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Stahl, Niel. "Making a Drug You Hope No One Will Ever Need Harnessing the Power of Technology for Good". Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Ebola Treatment Massively Cuts Death Rate, But It's No Cure". Futurity. 2019-08-16. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "FDA Approves First Treatment for Ebola Virus". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 14 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Check Hayden, Erika (May 2018). "Experimental drugs poised for use in Ebola outbreak". Nature. 557 (7706): 475–476. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..475C. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-05205-x. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 29789732.

- WHO: Consultation on Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered and Investigational Interventions for Ebola virus Disease. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ebola/MEURI-Ebola.pdf

- "NIH VideoCast - CC Grand Rounds: Response to an Outbreak: Ebola Virus Monoclonal Antibody (mAb114) Rapid Clinical Development". videocast.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- "Two Ebola drugs show promise amid ongoing outbreak". Nature. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo". WHO. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Mole, Beth (2019-08-13). "Two Ebola drugs boost survival rates, according to early trial data". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- "Independent monitoring board recommends early termination of Ebola therapeutics trial in DRC because of favorable results with two of four candidates". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2019-08-12. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- McNeil, Jr., Donald G. (12 August 2019). "A Cure for Ebola? Two New Treatments Prove Highly Effective in Congo". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- Kingsley-Hall A. "Congo's experimental mAb114 Ebola treatment appears successful: authorities | Central Africa". www.theafricareport.com. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- "Ebola Treatment Trials Launched In Democratic Republic Of The Congo Amid Outbreak". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- Molteni, Megan (12 August 2019). "Ebola is Now Curable. Here's How The New Treatments Work". Wired. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "'Ebola is Now a Disease We Can Treat.' How a Cure Emerged from a War Zone".