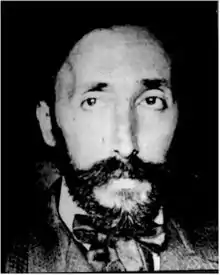

Rafael Barrett

Rafael Barrett, complete name Rafael Ángel Jorge Julián Barrett y Álvarez de Toledo, (Torrelavega, Spain, January 7, 1876 – Arcachon, France, December 17, 1910) was a Spanish writer, narrator, essayist and journalist, who developed most of his literary production in Paraguay, becoming an important figure of the Paraguayan literature during the twentieth century. He is particularly known for his stories and essays with profound philosophical content that exposed a vitalism that in some way anticipated existentialism. His philosophical and political statements in favor of anarchism are also well known.

Rafael Barrett | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Rafael Barrett January 7, 1876 |

| Died | December 17, 1910 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Known for | Journalist, narrator |

Notable work | El postulado de Euclídes (The Postulate of Euclides) Las voces del Ticino (The Voices of the Ticino) |

Youth

Barrett was born in Torrelavega in the year 1876, with the name of Rafael Ángel Jorge Julián Barrett y Álvarez de Toledo, in the bosom of a wealthy Spanish-English family, with his parents George Barret Clarke, natural from Coventry (England) and María del Carmen Álvarez de Toledo y Toraño, from Villafranca del Bierzo, province of León. At the age of twenty he moved to Madrid, to study engineering, there he became friends with Valle-Inclán, Ramiro de Maeztu and other members of the generation of ’98. In Madrid, he lived rebel boy, going from casino to casino and from woman to woman, alternating with visits to important literary gatherings in Paris and Madrid.

His constants attacks of rage lead him to confront with a member of the nobility, the duke of Arión, who agreed to a fight in middle of a function of the Circo de Pari. The duke of Arión was president of the Court of Honor that had disqualified him to duel with the attorney José María Azopardo, who had slandered him. All this made a big scandal in just six months.

This situation led him, in 1903, with his honor seriously damaged, to travel first to Argentina – where he started to write for different newspapers – and later to Paraguay, where he settled at the age of 29. In 1904 in October, he arrived to Villeta as a correspondent for the Argentine newspaper “El Tiempo” to report about the liberal revolution that was occurring at the moment, he immediately contacted the young intellectual that had adhered to the revolution. In Paraguay he formed a family and is where, according to his own words, he became “good”. Years later, he moved to Brazil as a result of a forced exile and then to Uruguay.

Life in Paraguay

Barrett settled in Asunción in December and started to work in the Statistic Office. In 1905 he married Francisca López Maíz, participated in the creation of the literary group “La Colmena” and manifests the first symptoms of tuberculosis.

In 1906, because of an argument originated by the presence of Ricardo Fuente in Buenos Aires, a duel between Barrett and Juan de Urquía was arranged. But Juan de Urquía eluded the duel with Barrett alleging his disqualification in Madrid. Days Later, Barrett beat a man called Pomés because he confused him with Juan de Urquía in a hotel in Buenos Aires.

In 1907, in Areguá is born his only son, Alejandro Rafael. In July 1908, Albino Jara organized a military insurrection. Barrett organized the attention to the wounded in the streets of Asunción. On October 3 of the same year, Barrett was arrested because of denounces about tortures and abuse that he published in Germinal (an anarchist newspaper that he owned) and on October 13, thanks to the help of the English Consul, he was released. He was exiled to Corumbá in the Brazilian Mato Grosso do Sul.

In February 1909 the political situation got better. Barret received warranties of his safety and established in San Bernardino, near Asunción. The Paraguayan journals open again their pages for him. In September he traveled to France. He had been maintaining correspondence with the doctor Quinton and decided to continue the treatment against the tuberculosis.

Career

His journeys through Argentina, Uruguay and particularly Paraguay defined him as a literate while developing his journalistic work. Ruined as he was, he never doubted in embracing the cause of the weaker holding his plume against the social injustice. In a certain manner, his time living in the misery made that he could liberate from a false life and to start living for the others.

The incidence of the miserable life conditions in a great part of South America reflected on his writings that were insistently turning into complaining journalism. His turn to a definitively anarchic not only carried problems with the more upper classes and the Paraguayan government (being imprisoned many times), but also many Paraguayan intellectuals gave him the back.

Work

The work of Rafael Barret is not too known. Short and not systematic, it was published almost entirely in journals of Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina. However, his thoughts notably influenced in Latin America and especially at the zone of De la Plata River. Although this influence wasn’t so deep, it was enough to be mentioned by Ramiro de Maeztu as a “figure in the history of America”.

Some of his central literary ideas are framed and defined in the regenerationist style. Is evident that, in this short examples, the coincidence of Barret with the characteristic tone of the regenerationist wave that flooded the Spanish thoughts because of the “disaster” of the ’98 and that have its main exponents in Costa, Picavea, Isern, and others, and its algid points in the press with the famous article published in “El tiempo”, a journal of the conservationist opposition, August 16 of 1898. The constant medical metaphors, the perception of Spain as a gravely injured country, the conviction that the military defeat was just a symptom of more deeper problems, the diagnosis of a progressive fall and the need of its “salvation”.

In “the Paraguayan pain” of Barret we see reflected the deep love that he felt to the Paraguayan people. The writings of Barret are from a notable intrinsic quality. In the opinion of José María Fernández Vázquez, if he would have had more time to develop his work, literary style and ideological strength, together would have formed one of the most interesting textual corpus of America.

Last years

It was in the new continent, more specifically in the Paraguay, where he made himself as a writer, discovered the true love and the paternity. However, once he reached these goals, he fell gravely ill. The historical circumstances of the Paraguay wasn’t good for receiving positively neither his radically critic ideas nor his questioning thoughts. With the publishing a series of articles What the Paraguayan yerba fields are, in which he reveals the almost slavish oppression of the mensús by the companies, Barret is faced to many powerful economic and politic interests. The pages of the journals where he used to publish were now closing and also he begins to feel the rejection of the local intellectuals, driving him to the isolation. As he bitterly confesses, "the custom of thinking at every single moment has some of shameful vice to the eyes of the common people and has made me a useful, even noxious, and hated being".

Because of his anarchic political ideas and his complaining about the social injustice he is imprisoned and banished first to the Brazilian Mato Grosso do Sul and finally to Montevideo. Being there he got in touch with the Uruguayan intellectual vanguards. But, the tuberculosis oppresses him and returns to the Paraguay as soon as the authorities allow it, and the local journals open their pages again to him.

He traveled to France in 1910 to try a new treatment for the tuberculosis. He died December 17 of 1910 at the age of 34 in the Regina Forèt Hotel in Arcachon, assisted by his aunt Susana Barret. He died away from his family and away from the only place that he considered as his fatherland, Paraguay, and without a single mention in the country from where he escaped: Spain.

During his life only saw published one book: "Actual Moralities", that was successful in Uruguay, a place where the intellectuals always connected with Barret. The luminous star of Rafael Barrett dimly reappears over the sky of Madrid when the America Editorial edits some of his work.

The relevance of Barrett

Three of the greatest writers from South America have expressed their deep admiration for the work of Barrett and his influence on them. In Paraguay, Augusto Roa Bastos said:

Barrett taught to us, the Paraguayan writers, to write. He introduced us in the grazing light and in the almost phantasmagoric nebulous of the reality that is delirious of its historical, social and cultural myths and counter-myths.

In Argentina, Jorge Luis Borges says in a letter of 1917 to his friend, Roberto Godel:

Now that we are talking about literary subjects I ask you if you know a great writer, Rafael Barrett, with a free and bold spirit. With tears in my eyes and on my knees I beg you that when you have a national or two to spend, go straight to Mendesky's, or any other library- and ask for a copy of "Looking the life" of this author. I think that it was published in Montevideo. Is a great book, and reading it soothed me from the foolishness of Giusti, Soiza, O'Reilly and my cousin Alvarito Melián Lafinur.

In Uruguay, José Enrique Rodó was amazed by his press articles. He wrote:

[...] It’s been a long time since that when I step out with someone I could ask about this kind of things, whether is or not the subject, I ask: Do you read La Razón? Have you noticed some articles signed by Rafael Barrett?

The work from Barrett, besides of the singular commitment with his time and circumstance, contains a beauty and an exceptional aesthetic value. In Paraguay is thought that Barrett begins from the conception of the critic realism in the vision of the narrative matter, and his short stories reveal great part of his notable aesthetic gift for the construction of the tale. The author that, through his work, with skill, sensitivity and beauty, gives exuberance to his work doesn’t forget the irony and the paradox, essentially intellectual resources.

My Anarchism

The social and political thoughts of Rafael Barret experiments, in the course of his seven years of expression, a clear transformation that goes from an individualism that converges vitalists Nietzsche-like features, to a fully assumed, mutual anarchism.

The inflection point in that evolution is produced between the end of 1906 and beginnings of 1907. On those dates, his concern about social subjects is becoming bigger and his critic position becoming more radical. Possibly it was the time required to assimilate the tough American reality ("the Paraguayan pain"), after of contact it, Barret enriches his spirit. The exuberant and conflictive American vitality filled the hole that the European intellectual ambient could have left on him. Is from 1908 that Barret begins to self-define as anarchist in his famous pamphlet My Anarchism.

The etymological sense of "absence of government" is enough for me. We have to destroy the spirit of authority and the prestige of the laws. That's it. That would be the work of the free exam. The fools think that anarchy is disorder and that without government the society will always end in chaos. They don't conceive other order that the one imposed from the exterior by the terror of the weapons. The anarchism, as I understand it, is reduced to the free political exam. [...] ¿So what we must do? Educate the others and us. Everything is resumed in the free exam. That our children examine our laws and despise them!

Published work

- "El postulado de Euclides" (The postulate of Euclides). Two articles of scientific divulgation published in the Contemporary Magazine. (5/30/1897)

- "Sobre el espesor y la rigidez de la corteza terrestre" (Of the thickness and rigidness of the Earth's surface). The only two articles of Barret published in Spain. (2/28/1898).

- In 1904, he wrote in The Spanish Mail of Buenos Aires and acted as secretary of the Spanish Republican League of the city.

- In 1905, he wrote regularly for El Diario of Asunción. He began to work at the department of engineers and the train.

- In 1906, his journalistic labor was increasing progressively. he wrote for Los Sucesos, La tarde, Alón, El Paraguay, El Cívico. At the same time, their work became closer to the social problems with a deep critic vision.

- In June 1908, he published in El Diario What the Paraguayan yerba fields are, complaining about the slavish situation of the mensús (the pawns of the yerba fields) in the Alto Paraná. The pressure of the companies made that the journals close their doors to him.

- In 1909, his book "Actual Moralities" had a big success.

Bibliography

- Rafael Barrett, "The Woman in Love" (english version of "La Enamorada")

- Rafael Barrett, A partir de ahora el combate será libre. Recopilación de artículos prologados por Santiago Alba Rico, Madrid, Ladinamo Libros, ISBN 84-607-6754-X

- Rafael Barrett "La Rebelión", Asunción del Paraguay, 15 de marzo de 1909

- Texto extraído por Philía de ANARKOS Literaturas libertarias de América del Sur. 1900; Compiladores: Jean Andreu, Maurice Fraysse, Eva Golluscio de Montoya; Ediciones CORREGIDOR, Buenos Aires, 1990.

- Francisco Corral "Vida y pensamiento de Rafael Barrett", Universidad Complutense, Madrid 2000. ISBN 84-8466-209-8

- Francisco Corral El pensamiento cautivo de Rafael Barrett. Crisis de fin de siglo, juventud del 98 y anarquismo. Editorial Siglo XXI. Madrid 1994. ISBN 978-84-323-0845-1

- Gregorio Moran "Asombro y búsqueda de Rafael Barrett", Anagrama, Barcelona 2007. ISBN 978-84-339-0790-5

- Catriel Etcheverri "Rafael Barrett, una leyenda anarquista", Capital intelectual, Buenos Aires 2007. Con prólogo de Abelardo Castillo.ISBN 978-987-614-021-8

- Asombro y búsqueda de Rafael Barrett, por Francisco Corral – ABC Digital

- ¿Descubrir a Barrett?, por Guillermo Rendueles

- Rafael Barrett, un anarquista brillante, falseado, algunos artículos de opinión

External links

- "My Anarchism" by Rafael Barrett

- RafaelBarrett.net, obras de Rafael Barrett

- Barrett, estudio, biografía, bibliografía y textos selectos de Barrett

- Rafael Barrett y la condición humana, estudio del pensamiento de Barrett por Francisco Corral

- Obra

- Evocación de Rafael Barrett Álvarez de Toledo

- A partir de ahora el combate será libre, recopilación de artículos de Rafael Barrett prologados por Santiago Alba Rico

- El pensamiento de Rafael Barrett: un "joven del 98" en el Río de la Plata, por Francisco Corral

- Rafael Barrett, textos de y sobre