Railcar

A railcar, (not to be confused with a railway car) is a self-propelled railway vehicle designed to transport passengers. The term "railcar" is usually used in reference to a train consisting of a single coach (carriage, car), with a driver's cab at one or both ends. Some railway companies, such as the Great Western, termed such vehicles "railmotors" (or "rail motors").

Self-propelled passenger vehicles also capable of hauling a train are, in technical rail usage, more usually called "rail motor coaches" or "motor cars" (not to be confused with the motor cars, otherwise known as automobiles, that operate on roads).[1]

The term is sometimes also used as an alternative name for the small types of multiple unit which consist of more than one coach. That is the general usage nowadays in Ireland when referring to any diesel multiple unit (DMU), or in some cases electric multiple unit (EMU).

In North America the term "railcar" has a much broader sense and can be used (as an abbreviated form of "railroad car") to refer to any item of hauled rolling-stock, whether passenger coaches or goods wagons (freight cars).[2][3][4] Self-powered railcars were once common in North America; see Doodlebug (rail car).

In its simplest form, a "railcar" may also be little more than a motorized railway handcar or draisine, otherwise known as a speeder.

Uses

Railcars are economic to run for light passenger loads because of their small size, and in many countries are often used to run passenger services on minor railway lines, such as rural railway lines where passenger traffic is sparse, and where the use of a longer train would not be cost effective. A famous example of this in the United States was the Galloping Goose railcars of the Rio Grande Southern Railroad, whose introduction allowed the discontinuance of steam passenger service on the line and prolonged its life considerably.

Railcars have also been employed on premier services. In New Zealand, although railcars were primarily used on regional services, the Blue Streak and Silver Fern railcars were used on the North Island Main Trunk between Wellington and Auckland and offered a higher standard of service than previous carriage trains.

In Australia, the Savannahlander operates a tourist service from the coastal town of Cairns to Forsayth, and Traveltrain operates the Gulflander between Normanton and Croydon in the Gulf Country of northern Queensland.

Propulsion systems

Steam

.jpg.webp)

William Bridges Adams built steam railcars at Bow, London in the 1840s. Many British railway companies tried steam railcars but they were not very successful and were often replaced by push-pull trains. Sentinel Waggon Works was one British builder of steam railcars.

In Belgium, M. A. Cabany of Mechelen designed steam railcars. His first was built in 1877 and exhibited at a Paris exhibition. This may have been the Exposition Universelle (1878). The steam boiler was supplied by the Boussu Works and there was accommodation for First, Second and Third-class passengers and their luggage. There was also a locker for dogs underneath. Fifteen were built and they worked mainly in the Hainaut and Antwerp districts.

The Austro-Hungarian Ganz Works built steam trams prior to the First World War. The Santa Fe Railway built a steam powered rail car using a body by American Car and Foundry, a Jacobs-Schupert boiler and a Ganz power truck in 1911. Numbered M-104, the experiment was a failure, and was not repeated.[5]

Petrol

In 1904 the Automotor Journal reported that one railway after another had been realising that motor coaches could be used to handle light traffic on their less important lines.[6] The North-Eastern railways had been experimenting “for some time” in this direction, and Wolseley provided them with a flat-four engine capable of up to 100 bhp (75 kW) for this purpose. The engine drove a main dynamo to power two electric drive motors, and a smaller dynamo to charge accumulators to power the interior lighting and allow electric starting of the engine. The controls for the dynamo allowed the coach to be driven from either end. For further details see 1903 Petrol Electric Autocar.

Another early railcar in the UK was designed by James Sidney Drewry and made by the Drewry Car Co. in 1906. In 1908 the manufacture was contracted out to the Birmingham Small Arms Company.

By the 1930s, railcars were often adapted from truck or automobiles; examples of this include the Buick- and Pierce-Arrow-based Galloping Geese of the Rio Grande Southern Railroad, and the Mack Truck-based "Super Skunk" of the California Western Railroad.

Diesel

While early railcars were propelled by steam and petrol engines, modern railcars are usually propelled by a diesel engine mounted underneath the floor of the coach. Diesel railcars may have mechanical (fluid coupling and gearbox), hydraulic (torque converter) or electric (generator and traction motors) transmission.

Electric

Electric railcars and mainline electric systems are rare, since electrification normally implies heavy usage where single cars or short trains would not be economic. Exceptions to this rule are or were found for example in Sweden or Switzerland. Some vehicles on tram and interurban systems, like the Red Car of the Pacific Electric Railway, can also be seen as railcars.

Battery-electric

Experiments with battery-electric railcars were conducted from around 1890 in Belgium, France, Germany and Italy. In the US, railcars of the Edison-Beach type, with nickel-iron batteries were used from 1911. In New Zealand, a battery-electric Edison railcar operated from 1926 to 1934. The Drumm nickel-zinc battery was used on four 2-car sets between 1932 and 1946 on the Harcourt Street Line in Ireland and British Railways used lead–acid batteries in a railcar in 1958. Between 1955 and 1995 DB railways successfully operated 232 DB Class ETA 150 railcars utilising lead–acid batteries.

As with any other battery electric vehicle, the drawback is the limited range (this can be solved using overhead wires to recharge for use in places where there are not wires), weight, and/or expense of the battery.

An example of a new application for zero emission vehicles for rail environments such as subways is the Cater MetroTrolley which carries ultrasonic flaw detection instrumentation.

Old-generation railcars

Steam railcar for the narrow gauge Niederösterreichische Landesbahnen (DE), built by Komarek of Vienna in 1903

Steam railcar for the narrow gauge Niederösterreichische Landesbahnen (DE), built by Komarek of Vienna in 1903 An early petrol-engined rail omnibus on the New York Central railroad

An early petrol-engined rail omnibus on the New York Central railroad Weitzer petrol electric railcar, 1903, French & German components, Austrian producer in Hungarian, now Romanian Arad

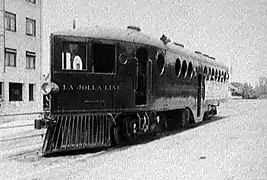

Weitzer petrol electric railcar, 1903, French & German components, Austrian producer in Hungarian, now Romanian Arad McKeen railmotor, 1904, futuristic design, early international success, unsolvable gear problems

McKeen railmotor, 1904, futuristic design, early international success, unsolvable gear problems

White Motor Company railcar in the collection of the Railtown 1897 State Historic Park. Jamestown, California

White Motor Company railcar in the collection of the Railtown 1897 State Historic Park. Jamestown, California.jpg.webp)

ČSD Class M 131.1

ČSD Class M 131.1

New-generation DMU and EMU railcars

A new breed of modern lightweight aerodynamically designed diesel or electric regional railcars that can operate as single vehicles or in trains (or, in “multiple units”) are becoming very popular in Europe and Japan, replacing the first-generation railbuses and second-generation DMU railcars, usually running on lesser-used main-line railways and in some cases in exclusive lanes in urban areas. Like many high-end DMUs, these vehicles are made of two or three connected units that are semi-permanently coupled as “married pairs or triplets” and operate as a single unit. Passengers may walk between the married pair units without having to open or pass through doors. Unit capacities range from 70 to over 300 seated passengers. The equipment is highly customisable with a wide variety of engine, transmission, coupler systems, and car lengths.

Institutional/regulatory Issues

Contrary to other parts of the world, in the United States these vehicles generally do not comply with Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) regulations and, therefore, can only operate on dedicated rights-of-way with complete separation from other railroad activities. This restriction makes it virtually impossible to operate them on existing rail corridors with conventional passenger rail service. Nevertheless, such vehicles may soon operate in the United States as manufacturers such as Siemens, Alstom and ADtranz affirm they may be able to produce FRA-compliant versions of their European equipment.

Existing systems

Light regional railcars are used by a number of railroads in Germany, and also in the Netherlands, Denmark, Italy, United States and Spain.

- Sprinter in San Diego, California

- Trillium Line in Ottawa, Canada

- Capital MetroRail in Austin, Texas

- A-train in Denton County, Texas

- SEPTA Cynwyd Line in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Ferrovia Trento-Malè in the region of Trento, Italy

- Ferrovia della Val Venosta in the province of South Tyrol, Italy (→ Italian language version)

- Ramal Talca-Constitución in the region of Maule, Chile

Manufacturers

Models of new-generation multiple-unit and articulated railcars include:

Multiple-unit and articulated railcars

When there are enough passengers to justify it, single-unit powered railcars can be joined in a multiple-unit form, with one driver controlling all engines. However, it has previously been the practice for a railcar to tow a carriage or second, unpowered railcar. It is possible for several railcars to run together, each with its own driver (as practised on the former County Donegal Railway). The reason for this was to keep costs down, since small railcars were not always fitted with multiple-unit control.

There are also articulated railcars, in which the ends of two adjacent coupled carriages are carried on a single joint bogie (see Jacobs bogie).

Railbuses

A variation of the railcar is the railbus: a very lightweight type of vehicle designed for use specifically on lightly-used railway lines and, as the name suggests, sharing many aspects of their construction with those of a road bus. They usually have a bus, or modified bus, body and four wheels on a fixed base, instead of running on bogies. Railbuses have been commonly used in such countries as the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

A type of railbus known as a Pacer based on the Leyland National bus is still widely used in the United Kingdom. New Zealand railcars that more closely resembled railbuses were the Leyland diesel railcars and the Wairarapa railcars that were specially designed to operate over the Rimutaka Incline between Wellington and the Wairarapa region. In Australia, where they were often called Rail Motors, railcars were often used for passenger services on lightly-used lines. In France they are known as autorails. Once very common, their use died out as local lines were closed. However, a new model has been introduced for lesser-used lines.

In Canada, after the cessation of their mainline passenger service, BC Rail started operating a pair of railbuses to some settlements not easily accessible otherwise.

In Russia, the Mytishchi-based Metrowagonmash firm manufactures the RA-1 railbus, equipped with a Mercedes engine. As of summer 2006, the Gorky Railway planned to start using them on its commuter line between Nizhny Novgorod and Bor.[7]

Uerdingen railbus in Germany

Uerdingen railbus in Germany Two axle British Rail Railbus in York, England

Two axle British Rail Railbus in York, England An Argentine TecnoTren railbus

An Argentine TecnoTren railbus

Road–rail vehicles

The term railbus also refers to a dual-mode bus that can run on streets with rubber tires and on tracks with retractable train wheels.

The term rail bus is also used at times to refer to a road bus that replaces or supplements rail services on low-patronage railway lines or a bus that terminates at a railway station (also called a train bus). This process is sometimes called bustitution.

Parry People Movers

A UK company currently promoting the railbus concept is Parry People Movers. Locomotive power is from the energy stored in a flywheel. The first production vehicles, designated as British Rail Class 139, have a small onboard LPG motor to bring the flywheel up to speed. In practice, this could be an electric motor that need only connect to the power supply at stopping points. Alternatively, a motor at the stopping points could wind up the flywheel of each car as it stops.

Draisine

The term "railcar" has also been used to refer to a lightweight rail inspection vehicle (or draisine).

Battery electric MetroTrolley for rail use (for ultrasonic rail flaw detection)

Battery electric MetroTrolley for rail use (for ultrasonic rail flaw detection) In its simplest form, an American speeder - with motor unit detachable by hand

In its simplest form, an American speeder - with motor unit detachable by hand With some weather protection, including mountable canvas side curtains

With some weather protection, including mountable canvas side curtains

See also

Categories

General

- Air brake (rail)

- Autorail

- British Rail BEMU

- British Rail Railbuses

- Budd Rail Diesel Car

- Budd SPV-2000

- Cater MetroTrolley

- CPH railmotor

- DEB railcar

- Diesel multiple unit

- Doodlebug (rail car)

- Draisine

- EIKON International

- Edwards Rail Car Company

- GWR railcars

- GWR steam rail motors

- Handcar

- Luxtorpeda

- McKeen Motor Car Company

- Railmotor

- Railroad car

- Railway brakes

- Road-rail vehicle

- Rail car mover- some of which

resemble HiRail trucks. - Schienenzeppelin

- Railroad speeder

- Stadler GTW

- Unimog

References

- www.parrypeoplemovers.com Archived 2009-01-06 at the Wayback Machine Light Railcars and Railbuses - Retrieved on 2008-06-09

- Brinckman, Jonathan (March 6, 2009). "Railcar orders, jobs in jeopardy". The Oregonian. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- "Trinity Eyes Stimulus". The Journal of Commerce. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- "Bill address railcar storage". Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- Worley, E.D. (1965). Iron Horses of the Santa Fe Trail. US: Southwest Railroad Historical Society. ASIN B0007EIUWE.

- "Motor Coaches for Railways", The Automotor Journal, January 23, 1904

- "Railbus RA-1 in Nizhny Novgorod", on the site "Public Transportation in Nizhny Novgorod" (in Russian)

External links

![]() The dictionary definition of railcar at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of railcar at Wiktionary

- Fleet Body Equipment

- Rail-Gear (Boatright Enterprises, Inc)

- The Road Rail Bus, an experimental bus for road and rail in the 1970s

- North Central Railcar Association (in Pennsylvania)

- Rail Motor Society (NSW, Australia)

- Stadler Rail

- North American Railcar Operators Association

- Search site for railcar for photos of 1930s European and New Zealand Railcars