Realization (figured bass)

Realization is the art of creating music, typically an accompaniment, from a figured bass, whether by improvisation in real time, or as a detained exercise in writing. It is most commonly associated with Baroque music.

Competent performers of the era were expected to realize a stylistically appropriate accompaniment from a mere harmonic sketch, called a figured bass, and to do it at sight. A system that allowed much flexibility, it became a lost art, but was revived in the 20th century by scholar-performers.

To realize a figured bass by writing down the actual notes to be played was (and is) a traditional exercise for students learning harmony and composition, and is used by music editors to make perfonrming editions.

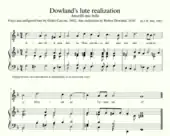

It was rare for established composers of the Baroque era to write down realizations. With few exceptions, those that have survived are short teaching demonstrations, or else student exercises. From this exiguous material must present-day scholars seek to recover the styles of the period, which varied considerably from time to time and place to place.

Concept

Composers of the Baroque era seldom wrote out the musical accompaniment (called the basso continuo, or simply continuo). Performers were expected to realize[9] one to suit the occasion, guided by no more than a bare sketch called a figured bass (or thorough bass). The figured bass consisted of a bass line written in normal staff notation, but marked with numerals or other symbols to indicate the harmony (see Ex. 1, first line). Indeed the entire Baroque period is sometimes referred to as the Figured Bass period.[10]

A basso continuo is analogous to the rhythm section of present-day jazz and popular bands; the figured bass, to the lead sheets used by such bands. However, realizing a figured bass has a challenging extra dimension. It is not enough that the correct harmonies (regarded as vertically stacked notes) be played: the notes must succeed each other horizontally according to certain voice leading rules, which in the Baroque era were quite strict.[11][12]

Execution

The realizer, while usually following the harmonic scheme indicated in the figuring, has a choice on such matters as rhythmic effect, chordal spacing, ornamentation, arpeggiation, imitation and counterpoint,[13] limited only by sound judgement and good taste,[14][15] and adherence to the genre's voice leading rules and stylistic conventions — ideally, those of the composer's time and place. Ex. 2 shows four realizations of the same figured bass by the Baroque composer Francesco Geminiani.

In early Baroque the bass was usually unfigured. However, by also considering the solo part the realizer could usually guess the harmonies ( Ex. 5).

Baroque era scores were riddled with copyist's or printer's errors, and sometimes an error of judgement by the composer himself. Accordingly, the realizer had (and has) to be ready to spot these and correct them. Thus, not only the figured harmonies, but even the written bass line can occasionally be altered.[16] Said C.P.E. Bach:

When the continuo is not doubled by other instruments, and the nature of the piece permits it, the accompanist may make impromptu modifications in the bass line with a view to securing correct and smooth progressions of the inner parts, just as he would modify faulty figuring. And how often has this to be done!'[17]

Benefits

John Butt has argued that figured bass is an instance of "purposely incomplete" notation conferring a positive advantage.[18] Accompaniments improvised from a figured bass line can be made to suit varying circumstances e.g. tempi, instrumentation, and even the hall acoustics.[19][20] Further, wrote Robert Donington:

It was not from mere casualness that baroque composers preferred to trust their performers with figured bass ... It was from the high value they set on spontaneity. They believed, and modern experience confirms, that it is better to be accompanied with buoyancy than with polished workmanship. An accompanist who can give rhythmic impetus to his part, adapt it to the momentary requirements of balance and sonority, thicken it here and thin it there, and keep every bar alive, can stimulate his colleagues and help to carry the entire ensemble along. This is not merely to fill in the harmony; nor is it merely to make the harmony into an interesting part; it is to share in the creative urgency of the actual performance.[19]

Drawbacks

Since few realizations were written down, except by pupils, not many have survived;[21] (A sonata movement by Bach — Ex. 4 — is believed to be a rare exception for this major composer.)[22] Where one has survived, it is precious evidence on the style of that particular time and place.[23][24] The notation "had this inherent defect — that no one who had not heard a composer play from his own figured bass parts could know the precise effects he produced or intended"[25] or contemplated (for styles and performing conventions varied much, not only from country to country, but from time to time).[26][27][28] So when these realizing traditions were lost, a passage in figured bass was a dead letter,[29] unless it could be somehow be revived by scholarship (see below). Writing as late as 1959 Benjamin Britten said:

[I]n England ... the music of Purcell is still shockingly unknown. It is unknown because so much of it is unobtainable in print, and so much of what is available is in realizations which are frankly dull and out of date. Because all Purcell's solo songs... have to be realized. We have these wonderful vocal parts, and fine strong basses, but nothing in between (even the figures for the harmony are often missing). If the tradition of improvisation from a figured bass were not lost, this would not be so serious, but to most people now, until a worked-out edition is available, these cold, unfilled-in lines mean nothing, and the incredible beauty and vitality, and infinite variety of these hundreds of songs go undiscovered.[30]

In actual performance

Baroque era

Keyboard accompaniments (e.g. harpsichord or organ) were meant to be spontaneously realized from the figured bass notation, the performer filling in the harmonic sketch as he went along.[31][32] J.S. Bach wrote:

Figured bass is the most perfect foundation of music. It is executed with both hands in such a manner that the left hand plays the notes that are written, while the right adds consonances and dissonances thereto, making an agreeable harmony for the glory of God and the justifiable gratification of the soul.[33]

Though keyboards have received most attention in the literature, there is abundant evidence the harmony was often realized by hand-plucked instruments e.g. lute, theorbo, guitar or harp (Exs. 1, 3, 5).[34] Further, it was played chordally on the same cello that supplied the bassline;[35][36] or even on the solo violin itself — by double stopping (Ex. 7).[6] Praetorius recommended a judicious selection of trombones, regals, flutes, violins, cornetts, recorders, "or a boy may sing the top line of all".[37]

Early operas were produced from a score containing, mostly, just the vocal parts and figured bass (as in Ex. 6, without keyboard realization); these were elaborated and ornamented by the performers .

The resulting performance might relate to the score rather as a great jazz performance might relate to the melody and chords indicated in a fake book.[38]

The harmonic sketch in figured bass was only meant to be a suggestion, wrote Marc Pincherle, adding:

Vivaldi, under the figured bass of one of the concertos dedicated to Pisendel, specifies, in three words, per li coglione (for the.... fools). This means that an intelligent accompanist does not need figures — and also signifies that no limits are imposed on his harmonic or contrapuntal invention, since it is assumed that he knows his profession and that he has taste and discretion.[39]

In Georg Philipp Telemann's understanding, "There are occasions when the accompanist may not wish to sound all the notes shown in the figuring. He is just as much within his rights in leaving out part of what is figured as he is in adding to what is figured."[40]

Professionals

To realize a figured bass at sight was an expected accomplishment for any professional accompanist,[41] an essential part of his musical training.[42] In 1761 the nine-year old Muzio Clementi, to qualify for an organ post in Rome, passed a test where candidates were given a figured bass and told to perform an accompaniment, after which they were obliged to transpose it into various keys.[43] A top realizer had to be a master of composition, insisted Roger North (1710):

Altho a man may attain the art to strike the accords true to a thro-base [thorough bass] prescribed him according as it is figured, yet he may not pretend to be master of his part, without being a master of composition in general, for there is occasion of so much management in ye manner of play, sometimes striking only by accords, sometimes arpeggiando, sometimes touching ye air, and perpetually observing the emphatick places, to fill, forbear, or adorne, with a just favour, that a thro-base master, and not an ayerist, is but an abecedarian.[44]

Even more demanding was partimento, in which composers were taught to improvise not just an accompaniment but a fully-fledged composition.

Amateurs

In the 18th century not just professionals were expected to accompany from a figured bass. Music handbooks for amateurs proliferated, and most of these contained figured bass instructions.[45] Handel wrote a course in realization for the daughters of George II. It taught, not only how to improvise accompaniments, but even fugues. It is on sale today. [46]

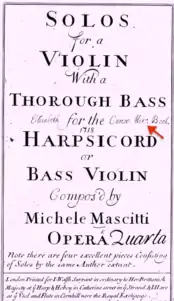

Music publishing originated in 18th century Europe, and it did so to cater for a growing army of cultivated amateurs. "Everybody sang or played, and the experience of teaming up with others was enormous fun. Composers were more than happy to oblige by writing music that was within the grasp of these amateurs".[47] The London publisher John Walsh — who sometimes passed off spurious pieces as and for the works of Corelli, Handel or Telemann — routinely issued his productions with figured basses. "Indeed, the chief consumers of the sonatas of Corelli and his imitators were not professional musicians but rather the gentlemen members of amateur music clubs. Walsh would have been able to count on a public of aristocratic and middle-class amateurs".[48]

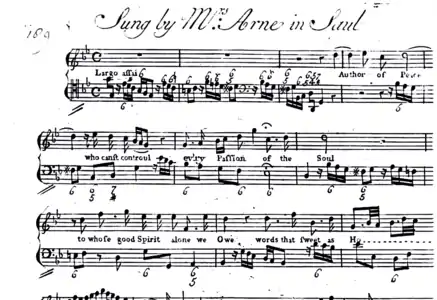

Walsh's Handel for amateurs, 1740

Walsh's Handel for amateurs, 1740 (Inside) Vocal part, with nothing but figured bass

(Inside) Vocal part, with nothing but figured bass The property of a lady, 1718

The property of a lady, 1718

Some amateurs were outstanding, wrote Mary Cyr:

David Hennebelle's recent research has shown that the status of 'amateur' was itself a broad one, defined principally as a group of both listeners and practitioners, united by the fact that they did not make their living in musical employment. They were, nevertheless, often astute musicians, some of whom sponsored concerts or were collectors of music, and their ranks also included composers and theorists. Hennebelle concluded that the skill of some amateurs exceeded that of professional musicians in some cases, and that among them figured a number of women who, despite having a different education in music (often in convents or from private music masters), excelled at several instruments and were multi-talented at several instruments.[49]

One such woman was the unusually gifted Princess Anne, Handel's lifelong friend,[50] whose continuo realizations impressed.[51]

For fashionable young ladies who only wanted to acquire the art as a social skill, there were tutors that taught a quick pragmatic way to play a continuo — of sorts.[52] Although not considered very elegant, a player could usually get by by arpeggiation,[53] (illustrated in Ex. 9). The ability of some amateurs to play from figured bass, and even direct an orchestra from the keyboard, persisted into the early Classical period.[54] In the United States, familiarity persisted farther. Not only could amateurs be found who could play from figured bass,[55] but briskly selling tune books — of popular music — were routinely published with figured bass parts, until the middle of the 19th century.[56]

Disuse

After the Baroque era the art died out.[57] By the time of the popular revival of J.S. Bach's music (by Mendelssohn, 1829) the performing traditions had been forgotten;[58] musicians took no account of Bach's figured basses; they played him without a continuo realization — sometimes with grotesque results.[59][60] Here and there a Brahms could be found who was adept at continuo improvisation but the ordinary competent musician demanded a realized score.[61]

In 1949 William J. Mitchell wrote: "The extemporaneous realization of a figured bass is a dead art. We have left behind us the period of the basso continuo and with it all the unwritten law, the axioms, the things that were taken for granted; in a word, the spirit of the time".[62] That year American harpsichordist and musicologist Putnam Aldrich tried to revive the practice at a Pierre Monteux rehearsal of "absolutely authentic" Bach:

I began straightaway realizing the figured bass of the opening tutti. The conductor interrupted: 'What are those chords you are playing? Bach wrote no chords here!" I tried to explain that the figures under the cembalo part stood for chords, but he said, "If Bach wanted chords he would have written chords. This is to be an authentic performance. We shall play only what Bach wrote". And as an aside to the other musicians he said. "You see, musicologists always have their noses in books and forget to look at what Bach wrote".[63]

But a revival of the art of live realization was underway.

Modern revival

Already in 1935 the highly successful[64] recordings of the Brandenburg Concertos by the Busch Chamber Players had a continuo realization. Their 1948 Kingsway Hall concerts were the highlights of the London season; audiences, reported Adolf Aber, felt here, at last, was the music of Bach and Handel as it was meant to be performed.

To come straight to the point: the fundamental difference between a Busch performance and a 'normal' modern performance lies in the treatment of that one line, the basso continuo[65]

even though it had no pretence to be historically informed[66] — just plain, unobtrusive chords on a grand piano sounded by Rudolf Serkin[67] which may or may not have been written down in advance.

Interest in improvising historically informed realizations of figured bass was first revived by amateurs in England.[68][69] The early music pioneer Arnold Dolmetsch's The Interpretation of the Music of the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries (1915) had a chapter on realizing figured bass, richly illustrated with historical examples. Dolmetsch advocated spontaneity before academic pedantry. Thus, a "noble" specimen by Michael Praetorius was "just right for effect; but it would not get a high number of points in a musical examination".

[The old books] for the most part ... only teach how to build the chords in four parts from the figures and how to connect them faultlessly together. They hardly say anything about the practical and artistic sides of the question, which depend upon a more or less conventional freedom of treatment, and which constitute the life and beauty of the accompaniment.[70]

In 1931 Franck Thomas Arnold, who like Dolmetsch was a self-taught scholar,[72] published his pioneeringThe Art of Accompaniment from a Thorough-bass: As Practised in the XVIIth & XVIIIth Centuries. Wrote Arnold:

[N]o one who has once tasted the delight of playing an ex tempore accompaniment from the figures, as the composer intended it to be played, could ever again become reconciled to dependence on the taste of a [a modern] 'arranger'.[73]

Highly acclaimed by scholars and critics[74] — Ernest Newman said it was "the finest piece of musicography ever produced" in England[75] — Arnold's book was studied by a new breed of historically informed scholar-performers, including American Ralph Kirkpatrick[76] and Janny van Wering[77] and Ton Koopman[78] in the Netherlands. Other works were Thurston Dart, The interpretation of music (London, 1954);[79] Robert Donington, The interpretation of early music (London, 1963);[80] and Peter Williams, Figured Bass Accompaniment (Edinburgh, 1970), of which a reviewer wrote, "So far as any sense can be made of a subject the essence of which is that it be not written down, Dr Williams has done it".[26]

By the end of the 20th century the scene had been transformed. Wrote American harpsichordist and editor Doris Ornstein: "[Thurston] Dart lived long enough to see his book, teaching, and personal example create a whole new breed of scholar-performers who can create stylish realizations. (In England, continuo playing is practically a cottage industry!)" .[81] Already by the late 1960s the lost art had been recovered by a number of harpsichord players, of which Gustav Leonhardt was the most prominent.[82] Under his direction the Conservatorium van Amsterdam abolished the written paper requiring the realization of a figured bass line, in favour of a practical one.[83] By 2013 the Conservatorium was offering a degree course in Basso Continuo Specialization, the first institute in the world to do so; a Master's degree was available.[82]

It was objected, however, that practitioners had evolved a 'generic' basso continuo style[84] characteristic of the late-20th century. Described by Lars Ulrik Mortensen as modest, discreet and unobtrusive, it was not what Baroque practitioners necessarily did.[85] Some would have played a "full-voiced" (thicker) style, for example (Exs. 8, 11)[86][87] or an embellished style (Ex. 10).[88] No real Baroque-era musician could have managed the diversity of styles and idioms that flourished in different lands and at different times in the period,[26] concerning which specific knowledge is patchy.[89] These required a new generation of specialist scholar-performers.

In writing

As a detained exercise in writing, figured bass has been realized when performers could not improvise, or as a teaching exercise, or when music publishers wanted to supply a pre-realised product.

Towards the end of the Baroque era, wrote Ernio Stipčević

the performance of the basso continuo became increasingly demanding with time, [and] the players were expected to possess more and more improvisational competence. The very peak of performing practices also marked their end, since the need for increasingly complex and precise harmonic accompaniment simultaneously contributed to the eradication of improvisational practices. [90]

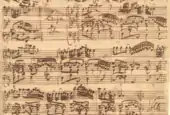

Bach's BWV 1097 was composed at the end of the Baroque era. Though it has a figured bass, its harmonies are demanding. Ex. 12 contains a written out realization by Bach's former pupil Johann Kirnberger .[91]

Music publishing

Figured basses are realized by editors of performing editions when performers cannot or do not wish to do it by themselves.

The early music revival in mid 19th century Germany, which by now had the most sophisticated music publishing industry in the world, created a demand for editions with pre-realized continuos since most performers did not know how to realize figured bass any more. As to that, two philosophical schools were bitter rivals, and nowhere did they clash more fiercely than on how to realize figured bass.[94]

The 'Romantic' school venerated the past, revering it for its own sake. Adherents included Friedrich Chrysander, Philipp Spitta, and Heinrich Bellermann. Their most impressive achievement was the Bach-Gesellschaft complete edition of J.S. Bach's works, "based on the original sources and with no changes, cuts, or additions"[95] — hence, with figured basses, but no realizations. They were jeered by the rival school for being mere musicologists with no artistic creativity.[96] To refute this, in 1870 Chrysander published an edition of Handel songs in which the figured basses were realized by indisputably talented musicians, including Johannes Brahms — one of their supporters.

The contending 'Hegelian' school believed that deep historical laws ensured that art manifested itself in increasingly perfect forms, and so early music ought to be modernised for present-day audiences. They sincerely believed they owed it to the music, since they were only doing what Bach, Handel, and so forth, would have done themselves, had they been alive to do it. Members of this school included Robert Franz, Selmar Bagge and Julius Schaeffer.[97] The Handel songs edition attracted their scorn. Franz penned a highly critical open letter in which, amongst other things, he caught out Brahms in the sin of writing a number of parallel fifths and octaves ("Handel's style allows for no schoolboy mistakes", he mocked) — which touched Brahms on a raw nerve.[98] In 1882 Franz himself brought out an edition of some of the same Handel songs. Unlike Brahms, Franz's realizations were florid and obtrusive (Exs. 13a vs. 13b).[99]

This dichotomy meant that, for generations after its revival, either Bach's music was published without any realizations,[58] — often being performed with no continuo at all, therefore[59] — or else with historically inauthentic realizations, criticised for being "purely fantastic",[100] "strangely unreal",[58] "ruthlessly corrupted",[101] "heavy, pianistic, and with a strangely nineteenth-century flavour", [102] just "a few dull chords",[23] or as conceited, pushy, usurping the composer's function.[103]

Modern editorial realizations, when they are provided at all, depend for their success on sound judgement and careful scholarship. There may be a dilemma. Said one modern editor: "A good realization depends on scholarship, imagination, sympathy with the soloist, familiarity with every nuance of the text, and consideration of the varying circumstances of performance"; and, for her eidition, she went to the extent of imagining a specific performance with a particular singer and the sonorities of a particular harpsichord,[81] which, logically, could have implied a single performance and a single sale. Already this dilemma had been faced by Brahms, who believed that "[ideally] each individual realization should be made with a view to a particular performance, taking into account specific forces, instruments, and location.[104]

Teaching and exams

J.S. Bach's pupils were routinely given a single melody line with a figured bass and told to realize a four-part chorale.[106] Or he made them realise figured basses by Italian composers (Ex. 14).[107] Only when they had mastered these exercises were they allowed to compose their own bass lines and harmonies.[106]

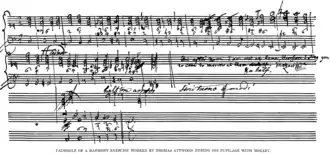

Such pedagogical methods were commonplace in the 18th century. Thomas Attwood, while Mozart's pupil, was made to realize figured basses. Once Attwood had acquired confidence, Mozart challenged him with a very chromatic figured bass — it swiftly progressed from the key of C to C#. (Back in England, these papers were passed on reverently from master to favourite pupil for several generations.)[108]

However, after the Baroque era — when basso continuo was employed no longer — the original purpose was lost sight of, since these educational methods had acquired a momentum of their own, carried on anyway by sheer inertia. Realization of figured bass became a puzzle-solving skill in its own right, bearing no relation to practical musicianship.[109] Realizing a figured bass was a routine exam question;[109] marks were impartially deducted for academic faults regardless of their artistic significance, if any.[110]

George Bernard Shaw recalled having to do those exercises:

"Seventy years ago I filled up the figured basses in Stainer's textbook of harmony[111] quite correctly. Any fool could, even though he were deafer than Beethoven".[112]

By 1932 R.O. Morris could say "Figured Bass as a means of teaching harmony is now universally discredited."[113]

See also

References and notes

- Dolmetsch 1915, p. 348.

- Dolmetsch 1915, pp. 358–9. (Francesco Geminiani, The art of Accompaniment, or A new and well digested method to learn to perform the Thorough Bass on the Harpsichord, 1753)

- Congleton 1981, p. 369.

- p repeat on the lute stop.

- Hill 1983, p. 200. "No modern editor would dare to write the parallel 5ths and octaves that confront us..." [See the red parallel lines.] Yet Florentine composers of the time stoutly defended the practice: ibid, 202-3.

- Whittaker 2012, p. 22.

- Mortensen 1996, p. 675.

- The piece was designed for two viols and harpsichord, or any two of those: Dolmetsch 1915, p. 352

- The word is thus spelled in both British and American English.

- Miller 1947, p. 69.

- Dolmetsch 1915, p. 344.

- Performers are supposed to avoid consecutive fifths and octaves, duplication of the leading note, and many other pitfalls.

- Donington 1965, pp. 223–4.

- Arnold 1931, p. 439.

- Pincherle 1958, p. 155.

- Donington 1965, pp. 242, 246. "It is occasionally desirable not merely to add to or subtract from the intervals shown by the figuring, but actually to contravene them in order to improve an awkward corner, such as may occur by oversight even in the best composers. Copyist's or printer's errors in the figuring are very common indeed; and, of course, if such an error is suspected, an intelligent performer will do his best not to be misled."

- Donington 1965, p. 246.

- Butt 2002, p. 106.

- Donington 1965, p. 223.

- Tyler 2011, p. 27.

- Arnold 1931, pp. 374 and n.3, 789.

- Collins & Seletsky 2014. "Two of Bach's accompaniments are thought to be examples of his own realizations in written-out form, since they are marked ‘cembalo obligato’ and are not in the same style as his usual composed harpsichord parts: they are [one aria and] the second movement of the Sonata in B minor for flute and harpsichord BWV 1030."

- Rose 1966, p. 29.

- Hill 1983, p. 194.

- Abdy Williams 1903, p. 184.

- Dalton 1971, p. 122.

- "... the vast terrain encompassed by the periods of Monteverdi and Mozart, the national styles of Italy, France, Germany and England, and the many different types of music that flourished in these lands in the 17th and 18th centuries. Well, of course no continuo player of the Baroque ever reckoned on having to manage all this; his style already existed where he lived, as did the musical idiom of the day, and all he had to be aware of ... was, whether he was in church, opera house or court concert": (Dalton, 1971).

- Mortensen 1996, p. 666.

- Aber 1948, pp. 169, 171.

- Britten 2003, p. 166.

- Dobbins 1980, p. 41.

- Donington & Buelow 1968, pp. 178–9.

- Schweitzer 1923a, p. 167.

- Garnsey 1966, p. 136.

- Whittaker 2012, p. 53 and passim. "For some reason the tradition of cello chordal accompaniment has been dismissed, ignored, or forgotten by most scholars and musicians. However, the practice of realization on the cello was a staple of the musical culture throughout Europe, especially during the Baroque period."

- Watkin 1996, pp. 645–6, 649-650, 653-4, 657-663.

- Dart 1967, pp. 105–7.

- Gould & Keaton 2000, p. 143.

- Pincherle 1958, pp. 154–5.

- Hammel 1978, p. 31.

- Donington 1982, p. 146.

- Dart 1965, p. 348.

- Sainsbury & Choron 1827, pp. 160–1.

- Donington & Buelow 1968, p. 179.

- Johnson 1989, p. 71.

- Handel & Ledbetter 1990, pp. 1, 2.

- Sturm 2000, p. 625.

- Swack 1993, p. 233.

- Cyr 2015, p. 26.

- Handel & Ledbetter 1990, pp. 1.

- Johnson 1989, p. 73.

- Johnson 1989, pp. 72–73.

- Revitt 1968, pp. 94–98.

- Ferguson 1984, p. 438.

- Barnes-Ostrander 1982, p. 363, 370.

- Karpf 2011, pp. 124, 128, 132-7, 140.

- Except among some English cathedral organists who continued to practise it up to the early 20th century: Abdy Williams 1903, p. 184; Arnold 1931, p. viii; Bergmann 1961, p. 31.

- Aber 1948, p. 171.

- Schweitzer 1923b, p. 445-6.

- "The public was treated to a dialogue between a contrabass and a flute, or even to a contrabass monologue" (Schweitzer, 1923b).

- Kelly 2006, pp. 194–5.

- Mortensen 1996, p. 665.

- Aldrich 1971, p. 466. "[In the second movement] even Monteux began to suspect that something was wrong. At the dress rehearsal he said to me in a whisper, 'In this movement you may add a few discreet chords'."

- Gutmann 2008. "One of the most important recordings ever made".

- Aber 1948, p. 169.

- Zaslaw 2001, p. 11.

- Best heard in e.g. the 2nd movement of Brandenburg Concerto No.2 in F.

- Leppard 1993, p. 27.

- Zaslaw 2001, p. 5-6.

- Dolmetsch 1915, pp. 342–344.

- Mortensen 1996, p. 668.

- Wakeling 1945, p. 156. Arnold's daytime job was lecturing in German language and literature at a Welsh university college.

- Arnold 1931, p. vii.

- See the main article F. T. Arnold

- Newman 1944, p. 2.

- Kirkpatrick 2014, pp. 44, 48.

- Wirth 2007, p. 22.

- Koopman 2019, p. 5.

- Dart 1967, p. ii.

- Zaslaw 2001, p. 6 n.2.

- Ornstein 1998, p. 13.

- de Goede 2018.

- Koopman 2019.

- Mangsen 1992, p. 499.

- Mortensen 1996, p. 665-8.

- Buelow 1963.

- Mortensen 1996, p. 666-8.

- Rose 1966, p. 2 9.

- Herissone 2006, p. 1.

- Stipčević 2009, p. 361.

- Arnold 1931, p. 789.

- Quoted in Kelly 2006, p. 192.

- Quoted in Kelly 2006, p. 193.

- Kelly 2006, p. 184.

- Kelly 2006, p. 182-83s.

- Kelly 2006, pp. 185–6.

- Kelly 2006, pp. 183–4.

- Kelly 2006, pp. 187–8. Brahms himself was making a collection of similar lapses by other composers.

- Kelly 2006, pp. 192–3.

- Schweitzer 1923b, p. 446.

- Dolmetsch 1915, p. 361.

- Donington 1965, p. 224.

- Bergmann 1961, p. 32.

- Kelly 2006, p. 197.

- F.G.E. 1900, p. 794a.

- Remeš 2017, p. 32.

- Spitta 1899, p. 293.

- Heartz 1973, p. 177.

- Orrey 1956, p. 298.

- Morris 1932, p. 147.

- Stainer 1872, pp. 126 et seq.

- Shaw 1948, p. 5.

- Morris 1932, p. 143.

Sources

- Abdy Williams, C.F. (1903). The Story of Notation. London: Walter Scott. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Aber, Adolf (1948). "On the Continuo in Bach". The Musical Times. 89 (1264): 169–171. doi:10.2307/933719. JSTOR 933719.

- Aldrich, Putnam (1971). "Wanda Landowska's Musique Ancienne". Notes. Music Library Association. 27 (3): 461–468. doi:10.2307/896554. JSTOR 896554.

- Arnold, F. T. (1931). The Art of Accompaniment from a Thorough-Bass as Practised in the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries. London: Oxford University Press, Humphrey Milford. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Barnes-Ostrander, M. E. (1982). "Domestic Music Making in Early New York State: Music in the Lives of Three Amateurs Author(s)". The Musical Quarterly. Oxford University Press. 68 (3): 353–372. doi:10.1093/mq/LXVIII.3.353. JSTOR 742006.

- Bergmann, Walter (1961). "Some Old and New Problems of Playing the Basso Continuo". Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 87th Sess. Taylor & Francis. 87: 31–43. doi:10.1093/jrma/87.1.31. JSTOR 765986.

- Britten, Benjamin (2003). Kildea, Paul (ed.). On Music. N.Y.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816714-8.

- Buelow, George J. (1963). "The Full-Voiced Style of Thorough-Bass Realization". Acta Musicologica. International Musicological Society. 35 (4): 159–171. doi:10.2307/932533. JSTOR 932533.

- Butt, John (2002). Playing With History: The Historical Approach to Musical Performance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01-3585.

- Collins, Michael; Seletsky, Robert E. (2014). "Improvisation - II. Western art music - 3. The Baroque period - (viii) Continuo realization". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- Cyr, Mary (2015). "Origins and performance of accompanied keyboard music in France". The Musical Times. 156 (1932): 7–26. JSTOR 24615806.

- Congleton, Jennie (October 1981). "The False Consonances of Musick". Early Music. 9 (4, Plucked-String Issue 2): 463–469. doi:10.1093/earlyj/9.4.463. JSTOR 3126689.

- Dalton, James (1971). "Review: Figured Bass Accompaniment by Peter Williams". The Galpin Society Journal. 24: 122–123. doi:10.2307/842026. JSTOR 842026.

- Dart, Thurston (1967). The Interpretation of Music (4 ed.). London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-031684-3.

- Dart, Thurston (1965). "Handel and the Continuo". The Musical Times. 106 (1467): 348–350. doi:10.2307/948713. JSTOR 948713.

- de Goede, Thérèse (2018). "About". theresedegoude.com. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Dobbins, Bill (1980). "Improvisation: An Essential Element of Musical Proficiency". Music Educators Journal. Sage. 66 (5): 40. doi:10.2307/3395774. JSTOR 3395774. S2CID 144282138.

- Dolmetsch, Arnold (1915). The Interpretation of the Music of the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries Revealed by Contemporary Evidence. London: Novello. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Donington, Robert (1965). The Interpretation of Early Music (2 ed.). London: Faber and Faber. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Donington, Robert; Buelow, George J. (1968). "Figured Bass as Improvisation". Acta Musicologica. International Musicological Society. 40 (2/3): 178–179. doi:10.2307/932411. JSTOR 932411.

- Donington, Robert (1982). Baroque Music: Style and Performance. A Handbook. New York: Norton. ISBN 0393300528.

- Ferguson, Faye (1984). "The Classical Keyboard Concerto: Some Thoughts on Authentic Performance". Early Music. Oxford University Press. 12 (4, The Early Piano I): 437–445. doi:10.1093/earlyj/12.4.437. JSTOR 3137973.

- F.G.E. (1900). "Thomas Attwood. (1765-1838)". The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. 41 (694): 788–794. doi:10.2307/3368298. JSTOR 3368298.

- Garnsey, Sylvia (1966). "The Use of Hand-Plucked Instruments in the Continuo Body: Nicola Matteis". Music & Letters. Oxford University Press. 47 (2): 135–140. doi:10.1093/ml/47.2.135. JSTOR 731202.

- Gould, Carol S.; Keaton, Kenneth (2000). "The Essential Role of Improvisation in Musical Performance". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Wiley. 58 (2): 143=148. doi:10.2307/432093. JSTOR 432093.

- Gutmann, Peter (2008). "Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concertos". Classical Notes. Retrieved 18 April 2020..

- Hammel, Maria (1978). "The Figured-bass Accompaniment in Bach's Time: A Brief Summary of Its Development and An Examination of Its Use, Together With a Sample Realization, Part II". Bach. Riemenschneider Bach Institute. 9 (1): 30–36. JSTOR 41640045.

- Handel, George Frideric; Ledbetter, David (1990). Continuo Playing According to Handel: His Figured Bass Exercises. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-318433-6.

- Haskell, Harry (1996). The Early Music Revival: A History. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-29162-6.

- Herissone, Rebecca (2006). 'To Fill, Forebear, Or Adorne': The Organ Accompaniment of Restoration Sacred Music. Ashgate; Royal Music Association. ISBN 0754641503.

- Heartz, Daniel (1973). "Thomas Attwood's Lessons in Composition with Mozart". Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association. 100: 175–183. doi:10.1093/jrma/100.1.175. JSTOR 766182.

- Hill, John Walter (1983). "Realized Continuo Accompaniments from Florence c1600". Early Music. Oxford University Press. 11 (2): 194–208. doi:10.1093/earlyj/11.2.194. JSTOR 3137832.

- Johnson, Jane Troy (1989). "The Rules for 'Through Bass' and for Tuning Attributed to Handel". Early Music. Oxford University Press. 17 (1): 70–74+77. doi:10.1093/earlyj/XVII.1.70. JSTOR 3127262.

- Karpf, Juanita (2011). ""In an Easy and Familiar Style:" Music Education and Improvised Accompaniment Practices in the U.S., 1820-80". Journal of Historical Research in Music Education. Sage. 32 (2): 122–144. doi:10.1177/153660061103200204. JSTOR 41300417. S2CID 141832388.

- Kelly, Elaine (2006). "Evolution versus Authenticity: Johannes Brahms, Robert Franz, and Continuo Practice in the Late Nineteenth Century" (PDF). 19th-Century Music. University of California Press. 30 (2): 182–204. doi:10.1525/ncm.2006.30.2.182. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2006.30.2.182.

- Kirkpatrick, Ralph (2014). Kirkpatrick, Meredith (ed.). Ralph Kirkpatrick: Letters of the American Harpsichorist and Scholar. University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-501-4.

- Koopman, Ton (2019). Translated by Dobbin, Elizabeth. "Editorial". Eighteentb Century Music. Cambridge University Press. 16 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1017/S1478570618000313.

- Leppard, Raymond (1993). Lewsi, Thomas P. (ed.). Leppard on Music: An Anthology of Critical and Personal Writings. New York: Pro/Am Music Resources.

- Mangsen, Sandra (1992). "Review: Continuo Playing According to Handel: His Figured Bass Exercises by David Ledbetter". Journal of the American Musicological Society. University of California Press. 45 (3): 498–506. doi:10.2307/831716. JSTOR 831716.

- Miller, Hugh Milton (1947). An Outline-History of Music. New York: Barnes and Noble. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Morris, R.O. (1932). Foundations of Practical Harmony & Counterpoint. II. London: Macmillan. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Mortensen, Lars Ulrik (1996). "'Unerringly Tasteful'?: Harpsichord Continuo in Corelli's Op.5 Sonatas Author(s)". Early Music. Oxford University Press. 24 (4): 665–679. doi:10.1093/em/24.4.665. JSTOR 3128062.

- Newman, Ernest (2 July 1944). "A Job for a Dictator?". Sunday Times.

- Ornstein, Doris (1998). "On Preparing A Performing Edition Of Handel's Cantata: Mi Palpita il Cor". Bach. Riemenschneider Bach Institute. 29 (1, AN ISSUE IN TRIBUTE TO THE WORK OF DORIS ORNSTEIN (1930-1992)): 9–37. JSTOR 41640445.

- Orrey, Leslie (1956). "Music as a University Study". The Musical Times. 97 (1360): 298–299. doi:10.2307/937874. JSTOR 937874.

- Pincherle, Marc (1958). Translated by Cazeau, Isabelle. "On the Rights of the Interpreter in the Performance of 17th- and 18th-Century Music Author(s)". The Musical Quarterly. Oxford University Press. 44 (2): 145–166. JSTOR 740448.

- Remeš, Derek (2017). "J. S. Bach's Chorales: Reconstructing Eighteenth-Century German Figured-Bass Pedagogy in Light of a New Source". Theory and Practice. Music Theory Society of New York State. 42: 29–53. JSTOR 26477743.

- Revitt, Paul J. (1968). "Domenico Corri's 'New System' for Reading Thorough-Bass". Journal of the American Musicological Society. University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society. 21 (1): 93–98. doi:10.2307/830388. JSTOR 830388.

- Rose, Gloria (1966). "A Fresh Clue from Gasparini on Embellished Figured-Bass Accompaniment". The Musical Times. 107 (1475): 28–29. doi:10.2307/953678. JSTOR 953678.

- Sainsbury, John S.; Choron, Alexandre (1827). A dictionary of musicians, from the earliest ages to the present time. I (2 ed.). London: Sainsbury & Co. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Shaw, Bernard (25 October 1948). "Basso Continuo". The Times.

- Schweitzer, Albert (1923a). J.S. Bach. I. Translated by Newman, Ernest. London: A & C Black. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Schweitzer, Albert (1923b). J.S. Bach. II. Translated by Newman, Ernest. London: A & C Black. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Stainer, John (1872). A Theory of Harmony (2 ed.). London: Rivington's. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Spitta, Philipp (1899). Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany. II. Translated by Bell, Clara; Maitland, J.A. Fuller. London: Novello. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Stipčević, Ennio (2009). "Review: The Performance of Italian Basso Continuo. Style in Keyboard Accompaniment in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries by Giulia NUTI". International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music. Croatian Musicological Society. 40 (2): 360–361. JSTOR 20696547.

- Sturm, George (2000). "Music Publishing". Notes, Second Series. Music Library Association. 56 (3): 628–634. JSTOR 899647.

- Swack, Jeanne (1993). "John Walsh's Publications of Telemann's Sonatas and the Authenticity of 'Op. 2'". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 118 (2): 223–245. doi:10.1093/jrma/118.2.223. JSTOR 766306.

- Tyler, James (2011). A Guide to Playing the Baroque Guitar. Indiana University Press.

- Wakeling, Donald R. (1945). "An Interesting Music Collection". Music & Letters. Oxford University Press. 26 (3): 159–161. doi:10.1093/ml/26.3.159. JSTOR 727649.

- Watkin, David (1996). "Corelli's Op.5 Sonatas: 'Violino e violone o cimbalo'?". Early Music. Oxford University Press. 24 (4): 645–663. doi:10.1093/em/24.4.645. JSTOR 3128061.

- Whittaker, Nathan H. (2012). Chordal Cello Accompaniment: The Proof and Practice of Figured Bass Realization on the Violoncello from 1660-1850 (DMA). Retrieved 12 April 2020 – via ProQuest.

- Wirth, Henriëtte (2007). Janny van Wering: 'onze Nederlandsche claveciniste' (DMA) (in Dutch). University of Utrecht. hdl:1874/23232.

- Zaslaw, Neal (2001). "Reflections on 50 Years of Early Music". Early Music. Oxford University Press. 29 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1093/em/29.1.5. JSTOR 3519085.