Roland W. Reed

Roland (Royal Jr.) W. Reed (June 22, 1864 – December 14, 1934), an American artist and photographer, was part of an early 20th century group of photographers of Native Americans known as pictorialists.

Pictorialists were influenced by the late 19th Century art movement, Impressionism, and their photography was characterized by an emphasis on lighting and focus. Rather than record an image as it was, pictorialists were more interested in re-creating an image as they thought it might have been. Part artist and part scientist, they endeavored to have their re-creations reflect not only the highest artistic value, but unquestioned ethnological accuracy as well. At the beginning of the 20th century a number of pictorialists, noticing the extremely deleterious impact of reservation life on Native Americans, wanted to recreate in photographs the Indian's life and ways as they had been in better times, rather than record how it had actually become.[1]

Early life

Roland Reed was born near Omro, Wisconsin about eight miles west of Oshkosh. His father, Royal Sr. (1827-1907), was a farmer and Civil War veteran. His mother, Mary Jane Hammond (1834-1904), was a homemaker. Roland was the fourth of six children. He and his youngest sibling, Mabel, were the only two to survive to adulthood.

Reed developed an early affinity for Native Americans through associations he had with neighboring Indians while growing up. He also fostered a thirst for adventure that would stay with him throughout his life.[2][3]

Reed left home at about the age of 18. He journeyed to Minnesota where he worked in a sawmill for a period of time. In 1885 he had his first exposure to the Plains Indians while working for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Shortly afterward, he returned to Minnesota, where he began a five-year period of exploration and adventure. Traveling down the Mississippi River to Memphis, TN, he then headed through the west across Arkansas, Texas, and New Mexico, finally winding up in Montana in 1890. There he went to work for the Great Northern Railway. He also employed the artistic skills that had been fostered by his mother doing portrait sketches of Piegan and Blackfeet Indians as well as landscape sketches and watercolors in various towns along the Great Northern route.

In 1893 he met Daniel Dutro, a Civil War veteran and photographer in Havre, MT. Reed apprenticed with Dutro, and shortly thereafter became Dutro's partner. They furnished Indian photographs to the news department of the Great Northern Railway as well as doing studio portrait photography. For a short time in 1897, Reed worked for the Associated Press in Alaska photographing the Klondike Gold Rush, but soon returned to Havre, MT.[3][4]

Career

Reed left Montana in 1899 and opened his own photo studio in Ortonville, MN, where his sister Mabel lived with her husband Ova Chamberlin.[5] He quickly developed a multi-state reputation as an excellent portrait photographer, especially of children, and a photographer of local landscapes.[6] As his business grew, he opened a second studio about 250 miles away in Bemidji, MN. After a few years, he began to periodically venture from his Bemidji Studio to photograph the Ojibwe Indians on nearby reservations.[3] In 1907 he sold his Ortonville and Bemidji studios and went to live near the Ojibwe Red Lake Reservation to begin his pursuit of portraying the North American Indian.[7] This task became his full-time mission for the next two years.

In 1909 Reed returned to Montana. He opened a studio in Kalispell, MT, near what would become the western entrance to Glacier National Park. In addition to portrait photography work, he sold copies of his Indian photographs and Native pottery, baskets, and rugs. He also began what would become over the next six years an extensive project of photographing the Plains Indians of Northern Montana and Southern Alberta, Canada—the Blackfeet, Piegan, Blood, Flathead, and Cheyenne.[8]

Much of Reed's effort was spent in and around Glacier National Park against the stunning majesty of the Rocky Mountains. In addition, he began to work with Louis Hill and the Great Northern Railroad on a number of different promotional and photographic projects. Many of his images were used in the Railroad's "See America First" campaign, which encouraged people to experience the grandeur of the Rocky Mountains by traveling via the Great Northern Railroad and staying at their grand lodges in and around Glacier National Park, rather than traveling to Europe to see the Alps.[9]

Reed also provided the Great Northern with large reprints of a number of his photos to decorate various stations along their line as well as their building at the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, CA.[10] During his time in Montana, Reed became part of a community of artists and writers in the area, many of whom also had associations with the Great Northern Railroad and Glacier National Park. Among these were artists Charlie Russell, Julius Seyler, Johannes Andersen, and writer Mary Roberts Rinehart. A number of other authors used Reed's images (although unattributed) in their books, including The White Quiver by Helen Fitzgerald Sanders; Enchanted Trails of Glacier National Park by Agnes Christina Laut, and Blackfeet Tales of Glacier National Park by James Willard Schultz.[11][12][13]

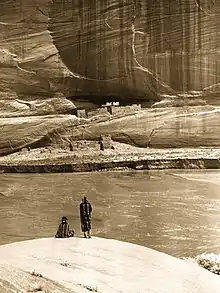

In 1913 Reed spent a number of months in Arizona photographing the Navajo and Hopi. Many of these photographs are against the extraordinary backdrop of Canyon de Chelly. During this time he developed a relationship with John Hubbell and his sons.[14] The Hubbells had various commercial enterprises throughout the Southwest.

Reed returned to Montana in 1913, and then opened a branch studio in San Diego, CA. Actually more of a souvenir shop than photo studio, he used the new location primarily to sell Indian pottery, baskets and rugs as well as prints of his photographs.[15] During his time in southern California, Reed became acquainted with a number of influential individuals, such as Hector Alliot and Charles Fletcher Lummis, who were deeply involved in preserving the culture of the Southwest Indians. They recommended that his photographs be prominently displayed at the 1915 Panama-California Exposition held at Balboa Park in San Diego.[16] His work was exhibited in the Indian Arts Building (later known as the House of Charm), and was awarded the Gold Medal for "pictures of an educational and historic value".[17] By this time he had also moved his studio to Coronado, but soon sold it to his assistant, Lou Bigelow. He returned to Kalispell to conclude any outstanding business, then began a period of semi-retirement, returning to Ortonville, MN where his sister Mabel still lived.[18]

Later life

Once back in Ortonville, Reed settled into a more quiet life that did not include studio photography work. He produced a catalog featuring 48 of his images that were for sale as prints in various sizes.

In 1916 he purchased land and built a cabin on Lower Bass Lake near Cable, WI, and for the next 5 years he divided his mostly leisure time between the two locations.[19]

In 1920, he relocated to Denver, CO, where he opened a new studio. Reed worked there until 1927, doing some studio and commercial photography as well as continuing to sell copies of his photographs.[20]

Wanderlust again set in. Reed returned for a short time to Minnesota, but then soon began work on yet another studio in San Diego. This venture never actually materialized and by 1930 he had fully retired to San Diego. In the early 1930s, Reed began to work on a book of his photographs under the working title Reed's Photographic Art Studies of the North American Indian.[21]

In 1934 he spent most of the year in St. Paul, MN collaborating with his cousin Roy Williams on another new project. The idea was to create a vehicle for selling copies of Reed photographs. They planned to develop a series of lectures in which various photographs would be presented via lantern slides and the pictured Native American life would be explained and detailed. A broad audience of different groups and organizations was anticipated. Copies of the photographs and lantern slides could then be purchased at the lectures.[22] Late that year, while returning to San Diego, he stopped to visit friends in Colorado Springs. While there, he suffered a fatal accident and died on December 14, 1934. Roland W. Reed was buried in Evergreen Cemetery, Colorado Springs, CO.[23]

After Reed's death his cousin, Roy Williams, was his primary beneficiary. Williams would go on to deliver the lectures they had been working on more than 3,000 times throughout the Upper Midwest. He continued to sell prints and photogravures of Reed's photographs until his death in 1949.[24] Since Reed's death, his work has remained largely unknown. The few photos that are published are generally either unattributed or misattributed. During his life, his efforts were mostly solitary and self-funded. Other than his work with the Great Northern Railroad, he had little interest in exploiting commercial or promotional items such as calendars.[25][26] At one point he turned down $15,000 for approximately 200 negatives to prevent them from being used in advertising for which he would have no input or control.[27] In 1915 National Geographic Magazine licensed the rights to about 40 of his photographs, but fewer than eight were actually published between 1916 and 1988.[28][29]

Image gallery

Ojibwe

Everywind, Roland W. Reed, 1907

Everywind, Roland W. Reed, 1907 Chief's Daughters, Roland W. Reed, 1908

Chief's Daughters, Roland W. Reed, 1908 Ojibwe woman tapping for sugar maple syrup

Ojibwe woman tapping for sugar maple syrup End Of The Chase, Roland W. Reed, 1908

End Of The Chase, Roland W. Reed, 1908 Nature's Mirror, Roland W. Reed, 1908

Nature's Mirror, Roland W. Reed, 1908 Ogamah, Roland W. Reed, 1907

Ogamah, Roland W. Reed, 1907 Papoose Pack-a-Back, Roland W. Reed, 1908

Papoose Pack-a-Back, Roland W. Reed, 1908 Ponemah, Roland W. Reed, 1908

Ponemah, Roland W. Reed, 1908 The Wooing, Roland W. Reed, 1908

The Wooing, Roland W. Reed, 1908 Solitary Man, Roland W. Reed

Solitary Man, Roland W. Reed The Colors, Roland W. Reed, 1907

The Colors, Roland W. Reed, 1907 The Hunters, Roland W. Reed, 1907

The Hunters, Roland W. Reed, 1907 The Moose Call, Roland W. Reed, 1908

The Moose Call, Roland W. Reed, 1908 The Old Trapper, Roland W. Reed, 1908

The Old Trapper, Roland W. Reed, 1908 The Parting, Roland W. Reed

The Parting, Roland W. Reed The Old Trappers Daughter, Roland W. Reed, 1908

The Old Trappers Daughter, Roland W. Reed, 1908 The Fisherman, Roland W. Reed, 1908

The Fisherman, Roland W. Reed, 1908

Blackfeet, Piegan

The Council, Roland W. Reed, 1912

The Council, Roland W. Reed, 1912 Blackfeet Indians At Ptarmigan Lake, Roland W. Reed

Blackfeet Indians At Ptarmigan Lake, Roland W. Reed Chief In Full Headdress, Roland W. Reed

Chief In Full Headdress, Roland W. Reed Curley Bear, Roland W. Reed

Curley Bear, Roland W. Reed Echoes Call, Roland W. Reed, 1913

Echoes Call, Roland W. Reed, 1913 In Camp, Roland W. Reed

In Camp, Roland W. Reed Into The Wilderness, Roland W. Reed, 1912

Into The Wilderness, Roland W. Reed, 1912 Last Star, Roland W. Reed

Last Star, Roland W. Reed.jpg.webp) Leaving Camp, Roland W. Reed (Variant)

Leaving Camp, Roland W. Reed (Variant) Little Bird, Roland W. Reed, 1908

Little Bird, Roland W. Reed, 1908 Long John, Roland W. Reed, 1907

Long John, Roland W. Reed, 1907 Medicine Man Yellow Plume, Roland W. Reed, 1912

Medicine Man Yellow Plume, Roland W. Reed, 1912 Meditation, Roland W. Reed

Meditation, Roland W. Reed Pow Wow, Roland W. Reed

Pow Wow, Roland W. Reed%252C_Roland_W._Reed%252C.jpg.webp) The Piegan (Lazy Boy), Roland W. Reed

The Piegan (Lazy Boy), Roland W. Reed Stolen Property, Roland W. Reed, 1912

Stolen Property, Roland W. Reed, 1912 Moccasin Foot, Roland W. Reed

Moccasin Foot, Roland W. Reed Prayer To The Thunderbird, Roland W. Reed, 1912

Prayer To The Thunderbird, Roland W. Reed, 1912 The Hunting Ground, Roland W. Reed, 1912

The Hunting Ground, Roland W. Reed, 1912 The Landmark, Roland W. Reed, 1912

The Landmark, Roland W. Reed, 1912 The Trail Makers, Roland W. Reed, 1912

The Trail Makers, Roland W. Reed, 1912 Tribute To The Dead, Roland W. Reed, 1912

Tribute To The Dead, Roland W. Reed, 1912 Up the Cutbank, Roland W. Reed,

Up the Cutbank, Roland W. Reed, Waiting For The Hunters, Roland W. Reed

Waiting For The Hunters, Roland W. Reed Watching The Herd, Roland W. Reed

Watching The Herd, Roland W. Reed Winter Count, Roland W. Reed

Winter Count, Roland W. Reed

Blood, Cheyenne, Flathead

Chief Steel, Roland W. Reed

Chief Steel, Roland W. Reed Little Martin, Roland W. Reed, 1913

Little Martin, Roland W. Reed, 1913%252C_Roland_W._Reed%252C_1912.tiff.png.webp) Memories (Ca Ca She), Roland W. Reed, 1912

Memories (Ca Ca She), Roland W. Reed, 1912

Navajo, Hopi

Broken Arrow, Roland W. Reed, 1913

Broken Arrow, Roland W. Reed, 1913 Shepherd Of The Hills, Roland W. Reed, 1913

Shepherd Of The Hills, Roland W. Reed, 1913 The Obelisk, Roland W. Reed, 1913

The Obelisk, Roland W. Reed, 1913 The Pottery Maker, Roland W. Reed, 1913

The Pottery Maker, Roland W. Reed, 1913 Stringing The Bow, Roland W. Reed, 1913

Stringing The Bow, Roland W. Reed, 1913 The Weaver, Roland W. Reed, 1913

The Weaver, Roland W. Reed, 1913 Sons Of Manuelita, Roland W. Reed, 1913

Sons Of Manuelita, Roland W. Reed, 1913

References

- Fleming & Lusky, Paula Richardson & Judith Lynn (1993). Grand Endeavors of American Indian Photography. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 99.

- Sanders, Helen Fitzgerald (1913). A History of Montana, Volume III. Chicago, IL: The Lewis Publishing Company. p. 1817.

- Reed, Roland W. Handwritten Notes. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Lawrence, Ernest R. (2012). Alone With the Past, The Life and Photographic Art of Roland W. Reed. Afton, MN: Afton Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-1-890434-84-7.

- Chamberlin, Mabel Reed (November 21, 1898). Letter to Roy F. Williams. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Leroux, Charles (April 17, 1979). "Roland Reed's Photographic Indian Legacy Lives". Chicago Tribune, Tempo Section.

- Bemidji Daily Pioneer. November 19, 1908. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Sanders, Helen Fitzgerald (1913). A History of Montana, Volume III. Chicago, IL: The Lewis Publishing Company.

- Peterson, Larry Len (2002). Call of The Mountains, The Artists of Glacier National Park. Tucson, AZ: Settlers West Galleries. p. 30.

- Lawrence, Ernest R. (2012). Alone with the Past, The Life and Photographic Art of Roland W. Reed. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-890434-84-7.

- Iron Horse West. Minnesota Museum of Art. 1976. p. 42.

- Farr, William E. (2009). Julius Seyler and the Blackfeet. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Dippie, Brian W. (2008). The 100 Best Illustrated Letters of Charles Russell. Ft. Worth, TX: The Amon Carter Museum.

- Reed, Roland W. (July 15, 1913). Letter to Roman Hubbel. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Kalispell Daily Interlake. February 21, 1914. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Kalispell Bee. May 29, 1914. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Laughead, W. B. (December 1916). "Roland Reed". The Minnesotan. 2 (6): 14–19.

- Ortonville Journal. August 1915. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Sullivan, David (2009). History of the Tri-Lakes Protective Association, Cable, WI: 6.37. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - The Rocky Mountain News. August 19, 1923. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Lawrence, Ernest R. (2012). Alone with the Past, The Life and Photographic Art of Roland W. Reed. Afton, MN: Afton Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-890434-84-7.

- Reed, Roland W (November 21, 1933). Letter to Roy Williams. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Reed, Roland W. (December 15, 1934, Certified Copy March 11, 1999.). State of Colorado Standard Certificate of Death, #554. Check date values in:

|date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Sullivan, David (2009). History of the Tri-Lakes Protective Association, Cable, WI: 3.4. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Lawrence, Ernest R. (2012). Alone with the Past, The Life and Photographic Art of Roland W. Reed. Afton, MN: Afton Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-890434-84-7.

- "Roland W. Reed: American Photographer". Museum Syndicate. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- Presbrey, Paul W. (December 29, 1934). "Invaluable Collection of Indian Photos Represent Years of Hardship in Artistic Pursuit". The St. Paul Daily News.

- "Letter from National Geographic Magazine to Paul S. Kramer". November 29, 1977. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Ojibwa Woman, Minnesota, 1907". National Geographic Society. Retrieved November 26, 2013.