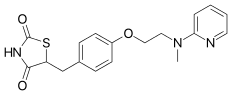

Rosiglitazone

Rosiglitazone (trade name Avandia) is an antidiabetic drug in the thiazolidinedione class. It works as an insulin sensitizer, by binding to the PPAR in fat cells and making the cells more responsive to insulin. It is marketed by the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) as a stand-alone drug or for use in combination with metformin or with glimepiride. First released in 1999, annual sales peaked at approximately $2.5-billion in 2006; however, following a meta-analysis in 2007 that linked the drug's use to an increased risk of heart attack,[1] sales plummeted to just $9.5-million in 2012. The drug's patent expired in 2012.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Avandia |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699023 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 99% |

| Protein binding | 99.8% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C8-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 3–4 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (64%) and fecal (23%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.108.114 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H19N3O3S |

| Molar mass | 357.43 g·mol−1 |

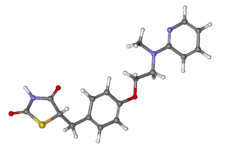

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Melting point | 122 to 123 °C (252 to 253 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

It was patented in 1987 and approved for medical use in 1999.[3] Despite rosiglitazone's effectiveness at decreasing blood sugar in type 2 diabetes mellitus, its use decreased dramatically as studies showed apparent associations with increased risks of heart attacks and death.[4] Adverse effects alleged to be caused by rosiglitazone were the subject of over 13,000 lawsuits against GSK;[5] as of July 2010, GSK had agreed to settlements on more than 11,500 of these suits.

Some reviewers recommended rosiglitazone be taken off the market, but an FDA panel disagreed, and it remains available in the U.S.[6] From November 2011 until November 2013, the federal government did not allow Avandia to be sold without a prescription from a certified doctor; moreover, patients were required to be informed of the risks associated with its use, and the drug had to be purchased by mail order through specified pharmacies.[7] In 2013, the FDA lifted its earlier restrictions on rosiglitazone after reviewing the results of a 2009 trial which failed to show increased heart attack risk.[8][9]

In Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended in September 2010 that the drug be suspended because the benefits no longer outweighed the risks.[10][11] It was withdrawn from the market in the UK, Spain and India in 2010,[12] and in New Zealand and South Africa in 2011.[13]

Medical uses

Rosiglitazone was approved for glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes, as measured by glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) as a surrogate endpoint, similar to that of other oral antidiabetic drugs.[14][15] The controversy over adverse effects has dramatically reduced the use of rosiglitazone.[16]

Published studies did not provide evidence that outcomes like mortality, morbidity, adverse effects, costs and health-related quality of life are positively influenced by rosiglitazone.[14]

Adverse effects

Heart failure

One of the safety concerns identified before approval was fluid retention. Moreover, the combination of rosiglitazone with insulin resulted in a higher rate of congestive heart failure. In Europe there were contraindications for use in heart failure and combination with insulin.[17]

A meta analysis of all trials from 2010 and 2019 confirmed a higher risk of heart failure and a double risk when rosiglitazone was administered as add-on therapy to insulin.[18][19] Two meta-analyses of real life cohort studies found a higher risk of heart failure compared to pioglitazone.[4][20] There were 649 excess cases of heart failure every 100,000 patients who received rosiglitazone rather than pioglitazone.

Heart attacks

The relative risk of ischemic cardiac events seen in pre-approval trials of rosiglitazone was similar to that of comparable drugs, but there was increased LDL cholesterol, LDL/HDL cholesterol ratio, triglycerides and weight.[21][22]

In 2005, at the insistence of the World Health Organization, GSK performed a meta-analysis of all 37 trials involving use of rosiglitazone, finding a hazard ratio of 1.29 (0.99 to 1.89). In 2006 the GSK updated the analysis, now including 42 trials and showing a hazard ratio of 1.31 (1.01 to 1.70). A large observational study comparing patients treated with rosiglitizone with patients treated with other diabetes therapies was performed at the same time and found a relative risk of 0.93 (95% C.I. 0.8 to 1.1) for those treated with rosiglitazone. The information was passed to the FDA and posted on the company website, but not otherwise published. GSK provided these analyses to the FDA, but neither the company nor the FDA warned prescribers or patients of the hazard.[23] According to the FDA, the Agency did not issue a safety bulletin because the results of the meta analysis conflicted with those of the observational study and with the results of the ADOPT trial.[24]

A meta-analysis in May 2007 reported the use of rosiglitazone was associated with a 1.4 fold increased risk of heart attack and a numerically higher (but non-significant) increase in risk of death from all cardiovascular diseases against control. It contained 42 trials of which 27 were unpublished.[1] Another meta analysis of 4 trials with follow-up longer than 1 year found similar results.[25] Nissen's meta analysis was criticized in a 2007 article by George Diamond et al. in the Annals of Internal Medicine. The authors concluded that Nissens' analysis had excluded trials with important data on the cardiovascular profile of rosiglitazone, had inappropriately combined trials of greatly differing design, and had inappropriately excluded trials with no cardiovascular events. The authors concluded that no firm conclusion could be drawn regarding whether rosiglitazone increased or decreased cardiovascular risk.[26] Investigators from the Cochrane Collaboration published a meta-analysis of their own on the use of rosiglitazone in Type II diabetes, concluding there was not sufficient evidence to show any health benefit for rosiglitazone. Noting the recent publication by Nissen, they repeated their meta analysis including only the trials included in the Nissen study that dealt with Type II diabetics. (The Nissen study included some trials in people with other disorders.) They did not find a statistically significant increase in cardiovascular events, but noted that all of the cardiovascular endpoints they analyzed showed a non-significant trend toward worse outcomes in the rosiglitazone arms.[27]

In July 2007 the FDA held a joint meeting of the Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee. FDA scientist Joy Mele presented a meta analysis examining the cardiovascular risk of rosiglitazone in completed clinical trials. The study found an overall 1.4x increase in risk of cardiovascular ischemic events relative to the control arms. The results were heterogenous, with clear evidence of increased risk relative to placebo but not relative to other diabetes treatments and higher risk associated with combinations of rosiglitazone with insulin or metformin.[28] Based on the 1.4x increased risk relative to control groups, FDA scientist David Graham presented an analysis suggesting that rosiglitazone had caused 83,000 excess heart attacks between 1999 and 2007.[29]:4[30] The advisory panel voted 20 : 3 that the evidence available indicated that rosiglitazone increased the risk of cardiovascular events and 22 : 1 that the overall risk:benefit ratio of rosiglitazone justified its continued marketing in the United States. The FDA placed restrictions on the drug, including adding a boxed warning about heart attacks, but did not withdraw it.[31]

In 2000 a study to address the concerns regarding cardiovascular safety was requested by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). GSK agreed to perform post-marketing a long-term cardiovascular morbidity/mortality study in patients on rosiglitazone in combination with a sulfonylurea or metformin: the RECORD study. The results as published in 2009 showed that rosiglitazone was non-inferior to treatment with metformin or a sulfonylurea with respect to the rate of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death. European regulators concluded that due in part to design limitations, the results neither proved nor eliminated concerns of excess cardiovascular risk.[17]

In February 2010, the FDA's associate director of drug safety, recommended rosiglitazone be taken off the market. In June 2010, they published a retrospective study comparing roziglitazone to pioglitazone, the other thiazolidinedione marketed in the United States and concluded rosiglitazone was associated with "an increased risk of stroke, heart failure, and all-cause mortality and an increased risk of the composite of AMI, stroke, heart failure, or all-cause mortality in patients 65 years or older".[32] The number needed to harm with roziglitazone was sixty. Graham argued rosiglitazone caused 500 more heart attacks and 300 more heart failures than its main competitor.

Two meta analyses released in 2010, one incorporating 56 trials and a second incorporating 164 trials reached conflicting conclusions. Nissen et al. found again an increased risk for heart infarction against control, but no increased risk for cardiovascular death.[33] Mannucci et al. found no statistically significant increase in cardiac events but a significant increase in heart failure.[34] A 2011 drug class review found an increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events.[35]

A meta-analysis of 16 observational studies released in March, 2011, compared rosiglitazone to pioglitazone, finding support for greater cardiovascular safety for pioglitazone. The meta-analysis involved 810 000 patients taking rosiglitazone or pioglitazone. The study suggests 170 excess myocardial infarctions, 649 excess cases of heart failure, and 431 excess deaths for every 100 000 patients who receive rosiglitazone rather than pioglitazone.[20][36] This was confirmed by another meta-analysis involving 945 286 patients in 8 retrospective cohort studies, most in the US.[4]

In 2012, the U.S. Justice Department announced GlaxoSmithKline had agreed to plead guilty and pay a $3 billion fine, in part for withholding the results of two studies of the cardiovascular safety of Avandia between 2001 and 2007.[37]

Death

There was no difference in all cause and vascular death in a meta-analysis of 4 trials against controls.[35][25] Two meta-analyses of cohort studies found excess deaths against pioglitazone.[4][20]

Stroke

An retrospective observational study performed using Medicare data found that patients treated with rosiglitazone had a 27% higher risk of stroke compared to those treated with pioglitazone.[38]

Bone fractures

GlaxoSmithKline reported a greater incidence of fractures of the upper arms, hands and feet in female diabetics given rosiglitazone compared with those given metformin or glyburide.[39] The information was based on data from the ADOPT trial[40] The same increase has been found with pioglitazone (Actos), another thiazolidinedione.

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, involving 13,715 patients and including both rosiglitazone- and pioglitazone-treated patients, showed an overall 45% increased risk of fracture with thiazolidone use compared with placebo or active comparator. It doubled the risk of fractures among women with type 2 diabetes, without a significant increase in risk of fractures among men with type 2 diabetes.[41]

Hypoglycaemia

The risk of hypoglycaemia is reduced with thiazolidinediones when compared with sulfonylureas; the risk is similar to the risk with metformin (high strength of evidence).[35]

Weight gain

Both thiazolidinediones cause a similar degree of weight gain to that caused by sulfonylureas (moderate strength of evidence).[35]

Eye damage

Both rosiglitazone and pioglitazone have been suspected of causing macular edema, which damages the retina of the eye and causes partial blindness. Blindness is also a possible effect of diabetes, which rosiglitazone is intended to treat. One report[42] documented several occurrences and recommended discontinuation at the first sign of vision problems. A retrospective cohort study showed an association between the use of thiazolidinediones and the incidence of diabetic macular edema (DME). Both use was associated with a 2,3 higher risk at 1 year and at 10 year follow-up, rising to 3 if associated with insulin.[35]

Hepatotoxicity

Moderate to severe acute hepatitis has occurred in several adults who had been taking the drug at the recommended dose for two to four weeks. Plasma rosiglitazone concentrations may be increased in people with existing liver problems.[43]

Contraindications

Both rosiglitazone and pioglitazone are contraindicated in people with NYHA Class III and IV heart failure. They are not recommended for use inheart failure.[44]

In Europe rosiglitazone was contraindicated for heart failure or history of heart failure with regard to all NYHA stages, for combined use with insulin and for acute coronary syndrome.[17] The European Medicines Agency recommended on 23 September 2010 that Avandia be suspended from the European market.[10][11]

Pharmacology

Rosiglitazone is a member of the thiazolidinedione class of drugs. Thiazolidinediones act as insulin sensitizers. They reduce glucose, fatty acid, and insulin blood concentrations. They work by binding to the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). PPARs are transcription factors that reside in the nucleus and become activated by ligands such as thiazolidinediones. Thiazolidinediones enter the cell, bind to the nuclear receptors, and alter the expression of genes. The several PPARs include PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ. Thiazolidinediones bind to PPARγ.

PPARs are expressed in fat cells, cells of the liver, muscle, heart, and inner wall (endothelium) and smooth muscle of blood vessels. PPARγ is expressed mainly in fat tissue, where it regulates genes involved in fat cell (adipocyte) differentiation, fatty acid uptake and storage, and glucose uptake. It is also found in pancreatic beta cells, vascular endothelium, and macrophages[45] Rosiglitazone is a selective ligand of PPARγ and has no PPARα-binding action. Other drugs bind to PPARα.

Rosiglitazone also appears to have an anti-inflammatory effect in addition to its effect on insulin resistance. Nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), a signaling molecule, stimulates the inflammatory pathways. NF-κB inhibitor (IκB) downregulates the inflammatory pathways. When patients take rosiglitazone, NF-κB levels fall and IκB levels increase.[46]

History

Rosiglitazone was approved by the US FDA in 1999 and by the EMA in 2000; the EMA however required two postmarketing studies on longterm adverse effects, one for chronic heart failure and the other for cardiovascular effects.[10]

Society and culture

Sales

US sales of the drug were of $2.2 billion in 2006.[47] Sales in 2Q 2007 down 22% compared to 2006.[48] 4Q 2007 sales down to $252 million.[49]

Though sales have gone down since 2007 due to safety concerns, Avandia sales for 2009 totalled $1.2 billion worldwide.[50]

Lawsuits

According to analysts from UBS, 13,000 suits had been filed by March 2010.[51] Included among those suing: Santa Clara County, California, which claims to have spent $2 million on rosiglitazone between 1999 and 2007 at its public hospital and is asking for "triple damages".[52] In May 2010, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) reached settlement agreements for some of the cases against the company, agreeing to pay $60 million to resolve 700 suits.[53] In July 2010, GSK reached settlement agreements to close another 10,000 of the lawsuits against it, agreeing to pay about $460 million to settle these suits.[54][55] [56]

In 2012, the U.S. Justice Department announced GlaxoSmithKline had agreed to plead guilty and pay a $3 billion fine, in part for withholding the results of two studies of the cardiovascular safety of Avandia between 2001 and 2007. The settlement stems from claims made by four employees of GlaxoSmithKline, including a former senior marketing development manager for the company and a regional vice president, who tipped off the government about a range of improper practices from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s.[37]

United States investigations

GlaxoSmithKline was being investigated by the FDA and the US Congress regarding Avandia.

Senators Democrat Max Baucus and Republican Charles Grassley filed a report urging GSK to withdraw Avandia in 2008 due to the side effects. The report noted the drug caused 500 avoidable heart attacks a month, and Glaxo officials sought to intimidate doctors who criticized the drug. It also said GSK continued to sell and promote the drug despite knowing the increased risk of heart attacks and stroke.[57]

The Senate Finance Committee, in a panel investigation, revealed emails from GSK company officials that suggest the company downplayed scientific findings about safety risks dating back to 2000. It was also alleged by the committee that the company initiated a "ghostwriting campaign", whereby GSK sought outside companies to write positive articles about Avandia to submit to medical journals.[58] GSK defended itself by presenting data that its own tests found Avandia to be safe, although an FDA staff report showed the conclusions were flawed.[59]

On July 14, 2010, after two days of extensive deliberations, the FDA panel investigating Avandia came to a mixed vote. Twelve members of the panel voted to take the drug off the market, 17 recommended to leave it on but with a more revised warning label, and three voted to keep it on the market with the current warning label.[60][61] The panel has come to some controversy, however; on July 20, 2010, one of the panelists was discovered to have been a paid speaker for GlaxoSmithKline, arousing questions of a conflict of interest. This panel member was one of the three who voted to keep Avandia on the market with no additional warning labels.[62][63]

In 2011 the FDA has decided on revising its prescribing information and medication guides for all rosilitazone containing medicines. The US label for rosiglitazone (Avandia, GlaxoSmithKline) and all rosiglitazone-containing medications (Avandamet and Avandaryl) now include the additional safety information and restrictions.[64][65] The revised labels restrict use to patients already taking a rosiglitazone-containing medicine or to new patients who are unable to achieve adequate glycemic control on other diabetes medications and to those, who in consultation with their healthcare provider, have decided not to take Actos (pioglitazone) or other pioglitazone-containing medicines for medical reasons.[66]

In June 2013 an FDA Advisory Committee reviewed all available data, including a re-adjudicated RECORD trial, found no evidence of increased cardiovascular risk with Avandia, and voted to remove the restrictions on Avandia marketing in the United States. In November 2013, the US FDA removed these marketing restrictions on the product.[67] Under the FDA’s instruction, Avandia’s maker, GlaxoSmithKline, had funded the Duke Clinical Research Institute to re-analyze the raw data from the study. At the 2010 panel, three panelists voted that the existing warnings were good enough; two were back in 2013. Seven voted to make those warnings more onerous, and five of them returned. But of the 10 who voted to restrict Avandia’s use, only four returned. And of the 12 who voted in 2010 to withdraw Avandia from the market, only three came back.[68]

European investigations

In 2000 a study to address the concerns regarding cardiovascular safety was requested by the EMA, and the makers agreed to perform post-marketing a long-term cardiovascular morbidity/mortality study in patients on rosiglitazone in combination with a sulfonylurea or metformin: the RECORD study. The results as published in 2009 showed non-inferiority with regard to cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death when the treatment with rosiglitazone was compared with metformin or a sulfonylurea. For myocardial infarction, there was a non-statistically significant increase in risk. In their assessment, the European regulators acknowledged weaknesses of the study, such as an unexpectedly low rate of cardiovascular events and the open-label design, which may lead to reporting bias. They found that the results were inconclusive.[17] The European Medicines Agency recommended on 23 September 2010 that Avandia be suspended from the European market.[10][11]

According to a probe by the British Medical Journal in September 2010, the United Kingdom's Commission on Human Medicines recommended to the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) back in July 2010, to withdraw Avandia sale because its "risks outweigh its benefits". Additionally, the probe revealed that in 2000, members of the European panel in charge of reviewing Avandia prior to its approval had concerns about the long-term risks of the drug.[69][70]

New Zealand

Rosiglitazone was withdrawn from the New Zealand market April 2011 because Medsafe concluded the suspected cardiovascular risks of the medicine for patients with type 2 diabetes outweigh its benefits.[71]

South Africa

A notice issued by the Medicines Control Council of South Africa on July 5, 2011 stated that it had resolved on July 3, 2011 to withdraw all rosiglitazone-containing medicines from the South African market due to safety risks. It disallowed all new prescriptions of Avandia.[72]

Controversy and response

Following the reports in 2007 that Avandia can significantly increase the risk of heart attacks, the drug has been controversial. A 2010 article in Time uses the Avandia case as evidence of a broken FDA regulatory system that "may prove criminal as well as fatal". It details the disclosure failures, adding, "Congressional reports revealed that GSK sat on early evidence of the heart risks of its drug, and that the FDA knew of the dangers months before it informed the public." It reports, "the FDA is investigating whether GSK broke the law by failing to fully inform the agency of Avandia's heart risks", according to deputy FDA commissioner Dr. Joshua Sharfstein. GSK threatened academics who reported adverse research results, and received multiple warning letters from the FDA for deceptive marketing and failure to report clinical data.[73] The maker of the drug, GlaxoSmithKline, has dealt with serious backlash against the company for the drug's controversy.[74] Sales on the drug dropped significantly after the story first broke in 2007, dropping from $2.5 billion in 2006 to less than $408 million in 2009 in the US.[75]

In response to the rise in risk of heart attacks, the Indian government ordered GSK to suspend its research study, called TIDE, in 2010.[76][77] The FDA also halted the TIDE study in the United States.[78]

Three doctors' groups, the Endocrine Society, the American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, urged patients to continue to take the drug as it would be much worse to stop all treatment, despite any associated risk, but that patients could consult their doctors and begin a switch to a different drug if they or their doctors find concern.[79][80][81] The American Heart Association said in a statement in June 2010: " ...the reports deserves serious consideration, and patients with diabetes who are 65 years of age or older and being treated with rosiglitazone should discuss the findings with their prescribing physician....". "For patients with diabetes, the most serious consequences are heart disease and stroke, and the risk of suffering from them is significantly increased when diabetes is present. As in most situations, patients should not change or stop medications without consulting their healthcare provider."[82][83]

As a result of the Avandia Affair, FDA required that cardiac safety be demonstrated for new drugs to treat type 2 diabetes. This process is described by Dr Robert Misbin in INSULIN-History from an FDA Insider, published June 1, 2020 on Amazon. Dr Misbin was the first FDA reviewer for rosiglitazone (Avandia) and cautioned about its potential to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Research

Rosiglitazone was thought to be able to benefit patients with Alzheimer's disease who do not express the ApoE4 allele,[84] but the phase III trial designed to test this showed that rosiglitazone was ineffective in all patients, including ApoE4-negative patients.[85]

Rosiglitazone may also treat mild to moderate ulcerative colitis, due to its anti-inflammatory properties as a PPAR ligand.[86]

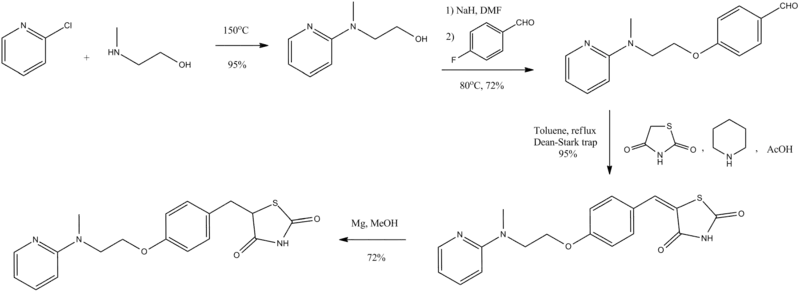

Synthesis

References

- Nissen SE, Wolski K (2007). "Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (24): 2457–71. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072761. PMID 17517853. S2CID 46431986.

- US 5002953

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 450. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Chen X, Yang L, Zhai SD (2012). "Risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality among diabetic patients prescribed rosiglitazone or pioglitazone: a meta-analysis of retrospective cohort studies". Chin. Med. J. 125 (23): 4301–6. PMID 23217404.

- "Glaxo Withheld Avandia Study, Ex-Regulator Said to Testify". Bloomberg.

- Gardiner Harris (February 19, 2010). "Controversial Diabetes Drug Harms Heart, U.S. Concludes". New York Times.

- "Most Popular E-mail Newsletter". USA Today. 2011-05-24.

- "Glaxo's Avandia Cleared From Sales Restrictions by FDA". Bloomberg.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (November 25, 2013). "FDA requires removal of certain restrictions on the diabetes drug Avandia".

- "European Medicines Agency recommends suspension of Avandia, Avandamet and Avaglim". News and Events. European Medicines Agency. 2018-09-17.

- "Call to 'suspend' diabetes drug". BBC News. 2010-09-23.

- "Drugs banned in India". Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Dte.GHS, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- "Diabetes drug withdrawn". Stuff.co.nz. NZPA. 17 February 2011. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Richter B, Bandeira-Echtler E, Bergerhoff K, Clar C, Ebrahim SH (2007). "Rosiglitazone for type 2 diabetes mellitus". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006063. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006063.pub2. PMC 7389529. PMID 17636824.

- Selvin E, Bolen S, Yeh HC, Wiley C, Wilson LM, Marinopoulos SS, Feldman L, Vassy J, Wilson R, Bass EB, Brancati FL (2008). "Cardiovascular outcomes in trials of oral diabetes medications: a systematic review". Arch. Intern. Med. 168 (19): 2070–80. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.19.2070. PMC 2765722. PMID 18955635.

- Ajjan RA, Grant PJ (2008). "The cardiovascular safety of rosiglitazone". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 7 (4): 367–76. doi:10.1517/14740338.7.4.367. PMID 18613801. S2CID 73109231.

- Blind E, Dunder K, de Graeff PA, Abadie E (2011). "Rosiglitazone: a European regulatory perspective" (PDF). Diabetologia. 54 (2): 213–8. doi:10.1007/s00125-010-1992-5. PMID 21153629. S2CID 33360502. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-30.

- Mannucci E, Monami M, Di Bari M, Lamanna C, Gori F, Gensini GF, Marchionni N (2010). "Cardiac safety profile of rosiglitazone: a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Int. J. Cardiol. 143 (2): 135–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.01.064. PMID 19328563.

- Wallach, Joshua D; Wang, Kun; Zhang, Audrey D; Cheng, Deanna; Grossetta Nardini, Holly K; Lin, Haiqun; Bracken, Michael B; Desai, Mayur; Krumholz, Harlan M; Ross, Joseph S (5 February 2020). "Updating insights into rosiglitazone and cardiovascular risk through shared data: individual patient and summary level meta-analyses". BMJ. 368: l7078. doi:10.1136/bmj.l7078. PMC 7190063. PMID 32024657.

- Loke YK, Kwok CS, Singh S (2011). "Comparative cardiovascular effects of thiazolidinediones: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". BMJ. 342: d1309. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1309. PMC 3230110. PMID 21415101.

- Nissen, Steven. "Rosiglitazone a critical overview. Presentation to FDA Advisory Committee" (PDF). Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Medical Officer's Review of New Drug Application 21-071: Rosiglitazone (Avandia)" (PDF). April 19, 1999. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- Nissen, Steven (2013). "Rosiglitazone: a case of regulatory hubris". BMJ. 347: f7428. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7428. PMID 24335808. S2CID 42125428.

- "Safety of Rosiglitazone Maleate (Avandia)".

- Singh, S; Loke, YK; Furberg, CD (Sep 12, 2007). "Long-term risk of cardiovascular events with rosiglitazone: a meta-analysis". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 298 (10): 1189–95. doi:10.1001/jama.298.10.1189. PMID 17848653. S2CID 41755937.

- Diamond GA, Bax L, Kaul S (2007). "Uncertain effects of rosiglitazone on the risk for myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death". Ann. Intern. Med. 147 (8): 578–81. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00182. PMID 17679700.

- Richter B, Bandeira-Echtler E, Bergerhoff K, Clar C, Ebrahim SH (2007). "Rosiglitazone for type 2 diabetes mellitus" (PDF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006063. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006063.pub2. PMID 17636824.

- "Dockets".

- "Staff report on GlaxoSmithKline and the diabetes drug Avandia", Committee on Finance, United States Senate, January 2010.

- David Graham, "Assessment of the cardiovascular risks and health benefits of rosiglitazone", Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology, Food and Drug Administration, 30 July 2007.

- "FDA Adds Boxed Warning for Heart-related Risks to Anti-Diabetes Drug Avandia. Agency says drug to remain on market, while safety assessment continues", Food and Drug Administration, 14 November 2007.

- Graham DJ, Ouellet-Hellstrom R, MaCurdy TE, Ali F, Sholley C, Worrall C, Kelman JA (2010). "Risk of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and death in elderly Medicare patients treated with rosiglitazone or pioglitazone". JAMA. 304 (4): 411–8. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.920. PMID 20584880.

- Nissen SE, Wolski K (2010). "Rosiglitazone revisited: an updated meta-analysis of risk for myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality". Arch. Intern. Med. 170 (14): 1191–1201. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.207. PMID 20656674.

- Mannucci E, Monami M, Di Bari M, Lamanna C, Gori F, Gensini GF, Marchionni N (2010). "Cardiac safety profile of rosiglitazone: a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Int. J. Cardiol. 143 (2): 135–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.01.064. PMID 19328563.

- Jonas, Dan. "Drug Class Review: Newer Diabetes Medications, TZDs, and Combinations Final Original Report Drug Class Reviews". Oregon Health & Science University. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- Hughes S (27 March 2011). "More damning data on rosiglitazone". theheart.org. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- Thomas, Katie; Schmidt, Michael S. (July 2, 2012). "Glaxo Agrees to Pay $3 Billion in Fraud Settlement". The New York Times.

- Graham DJ, Ouellet-Hellstrom R, MaCurdy TE, et al. (July 2010). "Risk of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and death in elderly Medicare patients treated with rosiglitazone or pioglitazone". JAMA. 304 (4): 411–8. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.920. PMID 20584880.

- Cobitz, Alexander R (February 2007). "Clinical Trial Observation of an Increased Incidence of Fractures in Female Patients Who Received Long-Term Treatment with Avandia (rosiglitazone maleate) Tablets for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus" (PDF). (49.9 KiB). GlaxoSmithKline. Retrieved on 10 April 2007.

- Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, Herman WH, Holman RR, Jones NP, Kravitz BG, Lachin JM, O'Neill MC, Zinman B, Viberti G (2006). "Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (23): 2427–43. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa066224. PMID 17145742. S2CID 30076668.

- Loke, Y. K.; Singh, S.; Furberg, C. D. (6 January 2009). "Long-term use of thiazolidinediones and fractures in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 180 (1): 32–39. doi:10.1503/cmaj.080486. PMC 2612065. PMID 19073651.

- Kendall C, Wooltorton E (2006). "Rosiglitazone (Avandia) and macular edema". CMAJ. 174 (5): 623. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060074. PMC 1389823. PMID 16467508.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1399-1400.

- "rosiglitazone". DailyMed The National Library of Medicine.

- Yki-Järvinen H (2004). "Thiazolidinediones". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (11): 1106–18. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041001. PMID 15356308.

- Mohanty P, Aljada A, Ghanim H, Hofmeyer D, Tripathy D, Syed T, Al-Haddad W, Dhindsa S, Dandona P (2004). "Evidence for a potent antiinflammatory effect of rosiglitazone". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (6): 2728–35. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-032103. PMID 15181049.

- "FDA toughens Avandia warnings". Medical Marketing and Media. 2007-11-14.

- Rubin, Rita (2007-07-26). "FDA panels to weigh Avandia heart risks". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- "Glaxo Fourth-Quarter Profit Fell 10% on Avandia Sales (Update6)". Bloomberg. 2008-02-07.

- Ranii, David (2010-02-23). "Avandia fallout could hit Triangle". News & Observer. Archived from the original on 2011-03-04. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- Ranii, David (2010-03-05). "Avandia could cost GSK billions". News & Observer. Archived from the original on 2012-10-02. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- "California county sues Glaxo over diabetes drug". Boston Globe. 2010-03-01. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- Feeley J, Kelley T (2010-05-11). "Glaxo Said to Pay About $60 Million in First Avandia Heart-Risk Settlement". Bloomberg.

- Feeley J, Kelley T (2010-07-13). "Glaxo Said to Pay $460 Million to Settle Avandia Damage Suits". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2012-07-13.

- Dawber, Alistair (2010-07-14). "GSK 'settles Avandia claims' on first day of safety hearing". The Independent. London.

- "GSK settles bulk of Avandia suits for $460M". FiercePharma.

- "Interactive: Timeline: The story of Avandia | Need to Know". PBS. 16 July 2010.

- "Avandia's Fate May be Sealed Today".

- "Avandia Safety Questioned Again".

- "12 panel members recommend Avandia withdrawal". FiercePharma.

- "What is the meaning of the Avandia vote?". FiercePharma.

- Mundy A (2010-07-20). "Panelist Who Backed Avandia Gets Fees From Glaxo". The Wall Street Journal.

- Gallagher, James (2010-07-20). "Report: Avandia panelist paid by GSK".

- Ross JS, Jackevicius C, Krumholz HM, Ridgeway J, Montori VM, Alexander GC, Zerzan J, Fan J, Shah ND (2012). "State Medicaid programs did not make use of prior authorization to promote safer prescribing after rosiglitazone warning". Health Aff (Millwood). 31 (1): 188–98. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1068. PMC 3319744. PMID 22232110.

- O'Riordan M. "New rosiglitazone label includes restrictions on use". theheart.org. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- "GSK revises US Avandia label to include new restrictions on use". GlaxoSmithKline. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- "Rosiglitazone-containing Diabetes Medicines: Drug Safety Communication – Removal of Some Prescribing and Dispensing Restrictions". U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Herper, Matthew (2013-06-06). "Avandia Vote Ends An Era Of Drug Safety Scandals". Forbes. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Douglas, Jason (2010-09-06). "U.K. Medical Journal Questions Avandia License". The Wall Street Journal.

- "U.K. watchdogs vote for Avandia withdrawal". FiercePharma.

- "Diabetes drug to be withdrawn over heart risk fears". New Zealand Herald. Feb 17, 2011.

- Medicines Control Council. "Withdrawal of rosiglitazone-containing medicines from SA market". Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "After Avandia: Does the FDA Have a Drug Problem?". Time. Aug 12, 2010.

- "Will Avandia Be Yanked Off the Market?". US News.

- "Exclusive: Takeda launches Actos DTC campaign today". Medical Marketing and Media. 2010-07-15.

- Silverman E (2010-07-20). "An Undisclosed Conflict On The FDA Avandia Panel?". Pharmalot. Archived from the original on 2010-07-23.

- "Avandia Drug Trials Shut Down In India". CBS Detroit. 2010-07-14.

- "FDA Orders Glaxo to Stop an Avandia Trial". foodconsumer.org. Archived from the original on 2014-11-09.

- "Don't dump Avandia, diabetes groups urge patients". Reuters. 2010-07-15.

- Maugh II, Thomas H. (2010-07-15). "Patients taking Avandia should keep on doing so, doctor groups say". The Los Angeles Times.

- Katz, Neil (2010-07-16). "Avandia News: What You Need to Know". CBS News.

- "Booster Shots". The Los Angeles Times. 2010-06-29.

- "American Heart Association Comment: Advisory Committee Recommends that U.S. Food and Drug Administration Keep Rosiglitazone (Avandia) on the Market, Continue Clinical Trial of Safety and Efficacy". Health News. redOrbit.

- Risner ME, Saunders AM, Altman JF, Ormandy GC, Craft S, Foley IM, Zvartau-Hind ME, Hosford DA, Roses AD (2006). "Efficacy of rosiglitazone in a genetically defined population with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease". Pharmacogenomics J. 6 (4): 246–54. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500369. PMID 16446752.

- Gold M, Alderton C, Zvartau-Hind M, Egginton S, Saunders AM, Irizarry M, Craft S, Landreth G, Linnamägi U, Sawchak S (2010). "Rosiglitazone monotherapy in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study". Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 30 (2): 131–46. doi:10.1159/000318845. PMC 3214882. PMID 20733306.

- Lewis, JD (2008). "Will 2008 mark the start of a new clinical trial era in gastroenterology?". Gastroenterology. 134 (5): 1289. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.030. PMID 18471502.

- Cantello, Barrie C.C. (1994). "The synthesis of BRL 49653 – a novel and potent antihyperglycaemic agent". Bioorganic. 4 (10): 1181–1184. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(01)80325-5.

- 2° Source: The Art of Drug Synthesis. Douglas S. Johnson (Editor), Jie Jack Li (Editor) pp. 121–122.

External links

- MedlinePlus article

- Medscape

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Rosiglitazone