Rudolf Duala Manga Bell

Rudolf Duala Manga Bell (1873 – 8 August 1914) was a Duala king and resistance leader in the German colony of Kamerun (Cameroon). After being educated in both Kamerun and Europe, he succeeded his father Manga Ndumbe Bell on 2 September 1908, styling himself after European rulers, and generally supporting the colonial German authorities. He was quite wealthy and educated, although his father left him a substantial debt.

| Rudolf Duala Manga Bell | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King | |||||

Rudolf Duala Manga Bell | |||||

| Reign | 2 September 1908 – 8 August 1914 | ||||

| Coronation | 2 May 1910 | ||||

| Predecessor | Manga Ndumbe Bell | ||||

| Born | 1873 Douala, Kamerun | ||||

| Died | 8 August 1914 (aged 40-41) | ||||

| Wife |

| ||||

| |||||

| Father | Manga Ndumbe Bell | ||||

In 1910 the German Reichstag developed a plan to relocate the Duala people living along the river, to be moved inland to allow for wholly European riverside settlements. Manga Bell became the leader of pan-Duala resistance to the policy. He and the other chiefs at first pressured the administration through letters, petitions, and legal arguments, but these were ignored or rebutted. Manga Bell turned to other European governments for aid, and he sent representatives to the leaders of other Cameroonian peoples to suggest the overthrow of the German regime. Sultan Ibrahim Njoya of the Bamum people reported his actions to the authorities, and the Duala leader was arrested. After a summary trial, Manga Bell was hanged for high treason on 8 August 1914. His actions made him a martyr in Cameroonian eyes. Writers such as Mark W. DeLancey, Mark Dike DeLancey, and Helmuth Stoecker view his actions as an early example of Cameroonian nationalism.

Early life and reign

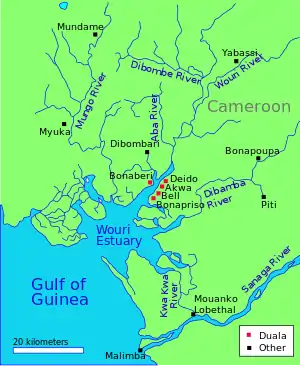

Manga Bell was born in 1873 in Douala in the German colony of Kamerun. He was the eldest son of Manga Ndumbe Bell, king of the Bell lineage of the Duala people. Manga Bell was raised to appreciate both African and European ways of life. His Westernized uncle David Mandessi Bell had a great impact on him,[1] and as a youth he attended school in both Douala and Germany.[2] During the 1890s he attended the Gymnasium of Ulm, Germany, although no direct record of his time there survives. Manga Bell was made Ein-Jähriger, indicating that he held a certificate for education beyond the primary level but below the Abitur earned for completion of secondary studies.[3] When the prince returned to Kamerun, he was one of the most highly educated men in the colony by Western standards.[4] He made other periodic visits to Europe, such as when he travelled to Berlin, Germany, and Manchester, England, with his father in 1902. In Manchester, he met the mayor at town hall and was mentioned in the October edition of the African Times (where the editor doubted that he and his father were actual royalty).[5] Manga Bell married Emily Engome Dayas, the daughter of an English trader and a Duala woman.[1]

When his father died on 2 September 1908, Manga Bell succeeded as the king of the Duala Bell lineage. He was traditionally installed on 2 May 1910 by the paramount chief of Bonaberi.[6] Manga Bell inherited an 8,000 mark pension,[7] cocoa and timber interests in the Mungo River valley, property and real estate in Douala,[8] and a lucrative position as head of an appeals court with jurisdiction over the Cameroon littoral.[9] His father and grandfather, Ndumbe Lobe Bell, left him in a strong political position with Bell dominant over the other Duala lineages.[4] However, his father also left him a substantial debt of 7,000 marks.[10] Rudolf Duala Manga Bell was forced to rent buildings to European interests and move his own offices inland to the Douala neighbourhood of Bali.[11] He owned 200 hectares of cocoa plantations in 1913, a large amount by Duala standards;[12] his debt had been reduced to 3,000 marks by 13 July 1912.[13]

Manga Bell's reign was European in character.[1] His relations with the Germans were largely positive, and he was viewed as a good citizen and collaborator.[11] Nevertheless, at times he ran afoul of the colonial administrators. In 1910, for example, the German authorities arrested him and accused him (with no proof) of collusion with a large bank robbery.[4]

Duala land problem

Manga Bell's real problems with the regime began later in 1910. The Germans outlined a plan to relocate the Duala people inland from the Wouri River to allow European-only settlement of the area. The expropriations affected all of the Duala lineages except Bonaberi,[11] so Duala public opinion was strongly against it, and for the first time in their history, the Duala clans presented a united front.[4] Manga Bell's position as leader of the dominant Bell clan, coupled with his character, education, and finances, made him a natural leader for this opposition. Manga Bell and other Duala rulers sent a letter to the Reichstag in November 1911 to protest the land seizures. The Germans were surprised at Manga Bell's involvement,[11] but they ignored the complaint. The chiefs sent another letter in March 1912. Still, the Germans moved forward with their plan on 15 January 1913.[14] The chiefs warned in writing on 20 February 1913 that this violation "may well prompt the natives to consider whether it might be wiser under the circumstances to revoke the [German-Duala Treaty of 1884 and enter into a treaty with another power."[15] Manga Bell argued that the expropriation plan ignored the treaty's promise "that the land cultivated by us now and the places the towns are built on shall be the property of the present owners and their successors"[16] and contradicted statements by Governor Theodor Seitz that he would leave Bell lands alone as he constructed a railroad in the colony.[17] The Germans countered that the German-Duala treaty gave them the authority to manage Duala lands as they saw fit. That August, they removed Manga Bell from office and from the civil service and stripped him of his annual pension of 3,000 marks.[18] In his place, they propped up his brother, Henri Lobe Bell.[19]

The Reichstag debated the expropriation for the first half of 1914. Manga Bell enlisted the aid of Hellmut von Gerlach, a German journalist. Gerlach managed to secure a suspension order from the Reichstag Budget Commission in March, but the order was overturned when Colonial Secretary Wilhelm Solf convinced elements of the press, businessmen in the colony, politicians, and other groups to finally rally behind the expropriation.[15] Manga Bell and the Duala requested permission to send envoys to Germany to plead their case, but the authorities denied them.[20] In secret, Manga Bell sent Adolf Ngoso Din to Germany to hire a lawyer for the Duala and pursue the matter in court.[21]

The desperate yet motivated Manga Bell, turned to other European governments and to the leaders of other African ethnic groups for support.[22] The contents of his correspondence with European powers are unknown; he may have simply sought to spread word of his cause.[23] His envoys to African leaders reached Bali, Balong, Dschang, Foumban, Ngaoundéré, Yabassi, and Yaoundé.[20] Karl Atangana, leader of the Ewondo and Bane peoples, kept Manga Bell's plan secret but urged the Duala leader to reconsider.[24] In Bulu lands on the other hand, Martin-Paul Samba agreed to contact the French for military support if Manga Bell petitioned the British.[25] However, there is no evidence that Manga Bell ever did so.[26] In Foumban, Ibrahim Njoya, sultan of the Bamum people, rejected the plan and informed the Basel Mission on 27 April 1914 that Manga Bell was planning a pan-Kamerun rebellion. The missionaries alerted the Germans.[25]

As King Manga Bell was prosecuted under the German occupation, he found a refuge by his relative and best friend, King Ekandjoum Joseph. The latter also claimed the rights of his kingdom and his Moungo people.

Historians are split on the nature of Manga Bell's actions. Mark W. DeLancey and Mark Dike DeLancey name him "an early nationalist", and Helmuth Stoecker says that his actions "had begun to organize a resistance movement embracing the whole of Cameroon and cutting across tribal differences".[15] However, Ralph A. Austen and Jonathan Derrick argue that "it is unlikely that any such radical action against the European regime was intended."[27]

On 6 May 1914 Bezirksamtmann Herrmann Röhm wrote to the Kuti Agricultural Station (where Manga Bell's envoy was being held),

We are not confronted with any direct danger of some kind of violent action by the Duala. For now the main value of the statements from Ndane [the envoy to Njoya] lies in the fact that they contain material for proceeding against those chiefs who are guilty of actual deliberate agitation in refusal of the expropriation and of resistance that reaches all the way over to Germany.[28]

On 1 June 1914 Röhm wrote to the administration in Buea that based on his calculations of Manga Bell's annual income from cocoa and timber exports, and accounting for his debts to European interests, the Duala merchants would likely not see it in their interests to oppose the expropriation further.[29] At the urging of Solf, the Germans arrested Manga Bell and Ngoso Din and charged them with high treason.[30] Their trial was held on 7 August 1914.[31] World War I had just begun, and an attack by the Allied West Africa Campaign in Kamerun was imminent; accordingly, the trial was rushed. No direct record of the proceedings survives. The dossier of evidence used against Manga Bell claimed that he had been raising funds from inland and that his outspoken opposition was causing unrest among the inland peoples.[23] The regime claimed that Manga Bell had admitted to contacting foreign countries for aid against Germany,[31] but a 1927 recollection by the official defense attorney—riddled as it is with inaccuracies and racist statements—claims that Manga Bell maintained his innocence throughout.[32] Requests for the accused men's lives to be spared came from Heinrich Vieter of the Catholic Pallottine Mission, the Basel Mission, and the Baptist Mission, but Governor Karl Ebermaier rejected their pleas.[33] On 8 August 1914,[34] Rudolf Duala Manga Bell and Adolf Ngoso Din were hanged. The Allies captured Douala seven weeks later on 27 September 1914.[35]

Legacy

Manga Bell's execution made him a martyr to the people of Cameroon and painted the Duala as an heroic people.[36] His story became legend[4] and came to represent "the myth of extreme colonial oppression, based upon the catastrophic climax of German rule in Douala".[37] Manga Bell was still popular well into the 1920s. "Tet'Ekombo", a hymn to him composed in 1929, has remained popular. In 1935 his body was exhumed and reburied behind his house in Bonanjo, Douala. An obelisk was erected there on 8 August 1936, the 20th anniversary of his execution.[38]

The Germans and later colonial powers in Cameroon became wary of the Duala and never again allowed a powerful chieftaincy to take hold among them.[39] After the French became the colonial power in French Cameroun after World War I, Rudolf Duala Manga Bell's brother Richard Ndumbe Manga Bell continued to fight to regain the lost Duala lands.[40] Manga Bell's son Alexandre Douala Manga Bell took office under the French in 1951.[19] His father's reputation as a Duala martyr lent Alexandre Douala Manga Bell great standing among the Duala.[41]

Cameroon faced a long civil war when the outlawed nationalist Union des Populations du Cameroun political party in the 1950s and '60s waged its maquis against French and Cameroonian forces. As a result, overt nationalist sentiment was shunned and figures such as Manga Bell were largely forgotten or only briefly treated in history books. However, signs show that Cameroon is coming to grips with its nationalistic past;[42] for example, in March 1985 the École Militaire Inter-Armes, part of the military of Cameroon named a graduating class of cadet officers after Manga Bell.[2]

Notes

- Austen and Derrick 126.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 168.

- Austen and Derrick 221 note 167.

- Austen and Derrick 132.

- Brunschwig 54; Green 23.

- Ngoh 350.

- Brunschwig 54.

- Austen and Derrick 130, 132

- Austen 14.

- Austen and Derrick 132–3.

- Austen and Derrick 133.

- Clarence-Smith 157.

- Austen and Derrick 221 note 169.

- Ngoh 106–7.

- Stoecker 172.

- Quoted in Stoecker 172.

- Austen and Derrick 129, Ngoh 107.

- Austen and Derrick 135, Ngoh 108.

- Austen and Derrick 144.

- Ngoh 107.

- Austen and Derrick 128; Ngoh 74, 107

- Austen and Derrick 128–9; Dorward 421.

- Austen and Derrick 136.

- Quinn 99.

- Austen and Derrick 136, Ngoh 108.

- Austen 21.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 168, Austen and Derrick 136.

- Letter quoted in Austen and Derrick 136.

- Austen and Derrick 130.

- Austen and Derrick 128; Stoecker 173.

- Ngoh 115.

- Austen and Derrick 222 note 179.

- Ngoh 74, 115; Austen and Derrick 222 note 177.

- Austen and Derrick 129 and Ngoh 115 both support this date; DeLancey and DeLancey 168 give the date as 14 August.

- Austen and Derrick 138.

- Austen and Derrick 129.

- Austen and Derrick 93.

- Austen and Derrick 171.

- Austen and Derrick 135.

- Hill 150 note 2.

- Austen 15.

- Bayart 43.

References

- Austen, Ralph A. (1983). "The Metamorphoses of the Middlemen: The Duala, Europeans, and the Cameroon Hinterland, ca. 1800–ca. 1960". The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 16, No. 1.

- Austen, Ralph A., and Derrick, Jonathan (1999): Middlemen of the Cameroons Rivers: The Duala and their Hinterland, c. 1600–c.1960. Cambridge University Press.

- Bayart, Jean-François (1989). "Cameroon". Contemporary West African States. Cambridge University Press.

- Brunschwig, Henri (1974). "De la Résistance Africaine à l'Impérialisme Européen". The Journal of African History, Vol. 15, No. 1.

- Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (2000). Cocoa and Chocolate, 1765–1914. London: Routledge.

- DeLancey, Mark W., and DeLancey, Mark Dike (2000): Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press.

- Dorward, D. C. (1986). "German West Africa, 1905–1914". The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 7: c. 1905–c. 1940. Cambridge University Press.

- Green, Jeffrey (1998). Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain, 1901–14. New York: Frank Cass Publishers.

- Hill, Robert A., ed. (2006). The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers: Africa for the Africans, 1923–1945, Vol. X. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ngoh, Victor Julius (1996): History of Cameroon Since 1800. Limbe: Presbook.

- Quinn, Frederick E. (1990): "Rain Forest Encounters: The Beti Meet the Germans, 1887–1916". Introduction to the History of Cameroon in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Stoecker, Helmuth (Zölner, Bernd, trans.) (1986). "Colonial Rule after the Defeat of the Uprisings". German Imperialism in Africa: From the Beginnings until the Second World War. London: C. Hurst & Col (Publishers) Ltd.