Sadako Sasaki

Sadako Sasaki (佐々木 禎子, Sasaki Sadako, January 7, 1943 – October 25, 1955) was a Japanese girl who became a victim of the Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki when she was two years old. Though severely irradiated, she survived for another ten years, becoming one of the most widely known hibakusha – a Japanese term meaning "bomb-affected person". She is remembered through the story of the one thousand origami cranes she folded before her death, and is to this day a symbol of the innocent victims of nuclear warfare.

Sadako Sasaki | |

|---|---|

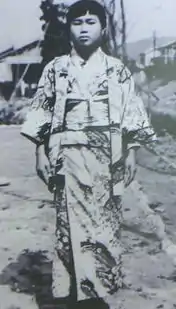

Sadako Sasaki in 1955 | |

| Born | Sadako Sasaki January 7, 1943 |

| Died | October 25, 1955 (aged 12) Red Cross Hospital Hiroshima, Japan |

| Cause of death | Leukaemia |

| Resting place | Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupation | Student |

| Website | www.sadako-jp.com |

Event

Sadako Sasaki was at home when the explosion occurred, about 1.6 kilometres (1 mi) away from ground zero. She was blown out of the window and her mother ran out to find her, suspecting she may be dead, but instead finding her two-year-old daughter alive with no apparent injuries. While they were fleeing, Sasaki and her mother were caught in black rain. Her grandmother rushed back to the house and was never seen again; later, she was presumed to be dead.

Aftermath

Sadako grew up like her peers and became an important member of her class relay team. In November 1954, Sasaki developed swellings on her neck and behind her ears. In January 1955, purpura had formed on her legs. Subsequently, she was diagnosed with acute malignant lymph gland leukaemia (her mother and others in Hiroshima referred to it as "atomic bomb disease"). She was hospitalized on February 21st, 1955,[1] and given no more than a year to live.

Several years after the atomic explosion an increase in leukaemia was observed, especially among children. By the early 1950s, it was clear that the leukaemia was caused by radiation exposure.[2]

She was admitted as a patient to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital for treatment and given blood transfusions on February 21, 1955. By the time she was admitted, her white blood cell count was six times higher compared to the levels of an average child.

Origami cranes

In August 1955, she was moved into a room with a girl named Kiyo, a junior high school student who was two years older than her. It was shortly after getting this roommate that cranes were brought to her room from a local high school club. Sasaki's father, Shigeo, told her the legend of the cranes and she set herself a goal of folding 1,000 of them, which was believed to grant the folder a wish. Although she had plenty of free time during her days in the hospital, Sasaki lacked paper, so she used medicine wrappings and whatever else she could scrounge; including going to other patients' rooms to ask for the paper from their get-well presents. Her best friend, Chizuko Hamamoto, also brought paper from school for Sasaki to use.

A popular version of the story is that Sasaki fell short of her goal of folding 1,000 cranes, having folded only 644 before her death and that her friends completed the 1,000 and buried them all with her. (This comes from the novelized version of her life Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes.) However, an exhibit which appeared in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum stated that by the end of August 1955, Sasaki had achieved her goal and continued to fold 300 more cranes.[3] Sadako's older brother, Masahiro Sasaki, says in his book The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki that she exceeded her goal.[4]

Death

During her time in the hospital, her condition progressively worsened. Around mid-October 1955, her left leg became swollen and turned purple. After her family urged her to eat something, Sasaki requested tea on rice and remarked "It's tasty". She then thanked her family, those being her last words. With her family and friends around her, Sasaki died on the morning of October 25, 1955, at the age of 12.

After her death, Sasaki's body was examined by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) for research on the effects of the atomic bomb on the human body. It was later revealed that the ABCC had also conducted tests on Sasaki while she was alive for the same reasons.

Memorials

After her death, Sasaki's friends and schoolmates published a collection of letters in order to raise funds to build a memorial to her and all of the children who had died from the effects of the atomic bomb, including another Japanese girl Yoko Moriwaki. In 1958, a statue of Sasaki holding a golden crane was unveiled in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. At the foot of the statue is a plaque that reads: "This is our cry. This is our prayer. Peace in the world."

There is also a statue of her in the Seattle Peace Park. Sasaki has become a leading symbol of the effects of nuclear war. Sasaki is also a heroine for many girls in Japan. Her story is told in some Japanese schools on the anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing. Dedicated to Sasaki, people all over Japan celebrate August 6 as the annual peace day.

Artist Sue DiCicco founded the Peace Crane Project in 2013 to celebrate Sadako's legacy and connect students around the world in a vision of peace. DiCicco and Sadako's brother co-wrote a book about Sadako, The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki, hoping to bring her true story to English speaking countries. Their website offers a study guide for students and an opportunity to "Ask Masahiro".

.jpg.webp) Japanese children all over the country create these little cranes in memory of Sadako Sasaki. Sadako and the cranes became a symbol for world peace in Japan after her death in 1955.

Japanese children all over the country create these little cranes in memory of Sadako Sasaki. Sadako and the cranes became a symbol for world peace in Japan after her death in 1955. Japanese schoolchildren dedicate a collection of origami cranes for Sadako Sasaki in Hiroshima Peace Park.

Japanese schoolchildren dedicate a collection of origami cranes for Sadako Sasaki in Hiroshima Peace Park. Sadako Sasaki statue in Peace Park in the University District of Seattle, Washington. Park was built by Floyd Schmoe.

Sadako Sasaki statue in Peace Park in the University District of Seattle, Washington. Park was built by Floyd Schmoe._(8212585335).jpg.webp) Memorial in Paris, France

Memorial in Paris, France

In popular culture

The tragic death of Sadako Sasaki inspired Dagestani Russian poet Rasul Gamzatov, who had paid a visit to the city of Hiroshima, to write an Avar poem, Zhuravli, which eventually became one of Russia's greatest war ballads.[5]

See also

References

- "Masahiro Sasaki: on surviving the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, his sister Sadako and his mission to advance peace". theelders.org. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- "Leukemia risks among atomic-bomb survivors". Radiation Effects Research Foundation). Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- "Special Exhibition 1". pcf.city.hiroshima.jp. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki (ISBN 9781938193019), Masahiro Sasaki, co-written with Sue DiCicco, founder of the Peace Crane Project.

- Bystryl, Andrey (July 4, 2018). "The great Dagestan poet Rasul Gamzatov". zvuk-m.com. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sadako Sasaki. |

- Sadako and the Paper Cranes — photos and other informational materials on the official homepage of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

- Sadako and the Atomic Bombing — Kids Peace Station at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

- Sadako Sasaki — The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki website

- Senzaburu Orikata — a 1797 book of origami designs to be used in the folding of thousand-crane amulets.

- "Cranes over Hiroshima" — lyrics to a song by Fred Small inspired by Sadako Sasaki.

- Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes

- Sadako Sasaki at Find a Grave

- "Daughter of Samurai" — a song by Russian rock band Splean, inspired by Sadako Sasaki.

- "Sadako e le mille gru di carta" is an album by Italian progressive rock band LogoS; published in 2020, seventy-five years after atomic bombing of Hiroshima, it tells the story of Sadako Sasaki.