Salt Lake Oil Field

The Salt Lake Oil Field is an oil field underneath the city of Los Angeles, California. Discovered in 1902, and developed quickly in the following years, the Salt Lake field was once the most productive in California;[1] over 50 million barrels of oil have been extracted from it, mostly in the first part of the twentieth century, although modest drilling and extraction from the field using an urban "drilling island" resumed in 1962. As of 2009, the only operator on the field was Plains Exploration & Production (PXP).[2] The field is also notable as being the source, by long-term seepage of crude oil to the ground surface along the 6th Street Fault, of the famous La Brea Tar Pits.

The adjacent and geologically related South Salt Lake Oil Field, not discovered until 1970, is still productive from an urban drillsite it shares with the nearby Beverly Hills Oil Field, also run by Plains Exploration and Production.[3]

Setting

The field is one of many in the Los Angeles Basin. Immediately to the west is the San Vicente Oil Field, and to the southwest the large Beverly Hills Oil Field. To the east are the Los Angeles City Oil Field and Los Angeles Downtown Oil Fields, the former one of the earliest to be drilled in the basin, and the one responsible along with the Salt Lake Field for the early twentieth-century oil boom in the area. Abutting the field to the southwest is the recently discovered and still active South Salt Lake Oil Field. The land above the two oil fields has a mean elevation of approximately 200 feet (61 m) above sea level, and slopes gently towards the south-southwest, away from the Santa Monica Mountains, draining via Ballona Creek towards Santa Monica Bay in the Pacific Ocean.[1]

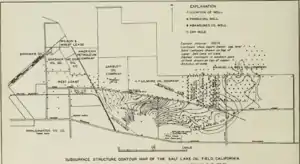

The productive region of the field is approximately three miles long by one mile across, with the long axis west to east along and parallel to Beverly Boulevard, from near its intersection with La Cienega Boulevard to past its intersection with Highland Avenue. All of the area is within the city of Los Angeles, and is heavily urbanized, making the Salt Lake Field one of a very few active oil fields in the United States in an entirely urban setting. While the entire former field area is dotted with abandoned wells, now entirely overbuilt with dense residential and commercial development, all active drilling takes place from a shielded, soundproofed drilling island adjacent to the Beverly Center, east of San Vicente Boulevard between Beverly Blvd. and 3rd Street. Since normal vertical drilling is impractical in a dense urban environment – active oil wells are loud, malodorous, and generally make poor neighbors – drilling from the tightly clustered wells in the island is directional, with wells slanting into different parts of the formation, similar to the technique used for drilling offshore fields from oil platforms. Only eleven wells, all in this drilling enclosure, remain active of the more than 450 once scattered over the landscape now known as Midtown Los Angeles. Other wells within the enclosure produce from the adjacent San Vicente and Beverly Hills fields.[2]

The adjacent South Salt Lake Oil Field is much smaller than its northern neighbor. Discovered in 1970, and only about a mile long by a thousand feet across, this field is exploited entirely from an urban drillsite at Genesee Avenue and Pico Boulevard within the bounds of the Beverly Hills Oil Field. The only active operator is also Plains Exploration and Production; as of 2009, there were 16 active wells in the South Salt Lake field.[3]

Geology

The field is near the northern edge of the Los Angeles Basin, about two miles (3 km) south of the Hollywood Hills, the nearest portion of the Santa Monica Mountains. The Santa Monica Fault, not known to be active, demarcates the boundary between the basin and the mountains. Several other faults cut through the field, including the 3rd Street Fault and the 6th Street Fault; the latter of these is presumed to be the conduit through which crude oil has emerged on the surface as the La Brea Tar Pits, which are at Hancock Park at the southern boundary of the oil field, near Wilshire Boulevard.[4] A layer of sediments of Quaternary age, both alluvial and shallow marine, forms a cap of approximately 200-foot (61 m) thickness on the underlying formations, several of which are oil-bearing. First is the Upper Pliocene Pico Formation, which is not petroleum-bearing in the Salt Lake field. Underneath the Pico are the late Miocene and Pliocene Repetto and Puente Formations. The Repetto Formation is a sandstone and conglomerate unit probably deposited in a submarine fan environment, and is a prolific petroleum reservoir throughout the Los Angeles Basin.[5] Underneath the Repetto is the late Miocene Puente Formation. All of these rock units are faulted and folded, forming structural traps, with oil trapped in anticlinal folds and along fault blocks.[5][6]

A total of six producing horizons, lettered A through F from top to bottom, have been identified in the Salt Lake field. Only Pool "A", first to be discovered, is in the Repetto, having an average depth of only about 1,000 feet (300 m) below ground surface (bgs). Pools "B" and "C" were found by 1904, and the deeper pools "D", "E", and "F", ranging from 2,850 to 3,300 feet (1,000 m) bgs, were found in 1960 with the resumption of drilling from the Gilmore Drilling Island.[7] Oil from the field is heavy and sulfurous, with API gravity ranging from 9 to 22, but usually 14-18; sulfur content is high at 2.73% in each pool.[8]

In the South Salt Lake field, two pools have been identified, both in 1970: the Clifton Sands and the Dunsmuir Sands, at 1,000 feet (300 m) and 2,500 feet (760 m) depth respectively. Oil is found in several steeply dipping sand units bounded by impermeable rocks; the sands pinch out towards the ground surface, and oil accumulates in the upper portions.[9] The oil in this field is slightly less heavy than in the main Salt Lake field, with API gravity ranging from 22 to 26. Sulfur content was not reported.[10]

History, production, and operations

In the 1890s, dairy farmer Arthur F. Gilmore found oil on his land, probably in the vicinity of the La Brea Tar Pits. The field was named after the Salt Lake Oil Company, the first firm to arrive to drill in the area. The discovery well was spudded (started) in 1902.[11] Details of the discovery well – depth, exact location, production rate – are not known.[12]

Development of the field was fast, as oil wells spread across the landscape, with drillers hoping to match the production boom taking place a few miles to the east at the Los Angeles City field. Peak production was in 1908.[13] By 1912, there were 326 wells, 47 of which had already been abandoned,[14] and by 1917 more than 450, which had by then produced more than 50 million barrels of oil.[15] After this peak, production declined rapidly. Land values rose, corresponding to the fast growth of the adjacent city of Los Angeles, and the field was mostly idled in favor of housing and commercial development. The early wells were abandoned; many of their exact locations are not known, and are now covered with buildings and roads.

By the 1960s, new developments in slant drilling technology were making possible exploitation of otherwise unrecoverable petroleum resources, and the urban fields in Los Angeles, such as the Salt Lake field, began to attract the attention of enterprising oil companies. In 1961, working from a drilling site near the Farmer's Market at the corner of 3rd Street and Fairfax Avenue, the Standard Oil Company of California again began to draw oil from the field, having recently discovered three new productive sand units (pools "D", "E", and "F"). Wells drilled into these producing horizons flowed without assistance only briefly, requiring pumping within a year or two.[4] In 1973, highly saline wastewater, formerly dumped into the city's storm drains, was reinjected into the reservoir both as a convenient, non-polluting disposal method, and to increase reservoir pressure to enhance oil recovery.[4] Similarly, gas produced from the oil field was reinjected into the reservoir between 1961 and 1971; facilities did not exist to capture, store, and transport it, as is the usual practice in current oil fields with nearby gas infrastructure.[16]

Operations at this drilling site, known as the "MacFarland Drilling Island" or the "Gilmore Drilling Island", continued until the 1990s.[16] This drilling island contained about 40 wells, and was dismantled beginning in 2001. The former 1-acre (4,000 m2) site is on The Grove Drive, across the street and west of Pan-Pacific Park. According to Texaco, the last oil company to own it, the site had become uneconomic to operate; towards the end the depleted oil field was only yielding about 30 barrels of oil a day from that location.[11]

With the shutting down of the Gilmore drilling island, royalty payments to many of the property owners of the land directly over the field ended. Some of them had been receiving monthly checks for as much as $2,500,[11] a situation similar to that at the Beverly Hills field.

Originally, Los Angeles planned to put a Metro subway line along Fairfax Avenue, but chose to reroute it because of the high levels of methane gas in the subsurface environment, since this flammable gas posed a safety risk.[17] It was only later that the oil field was recognized as the source of the methane gas. This hazard was realized spectacularly on the night of March 24, 1985, when a Ross clothing store filled with gas overnight and exploded, injuring 23 people.[1]

1985 Ross Dress for Less explosion

Seepage of methane upwards along conduits, such as faults and old well boreholes, caused an explosion at a Ross Dress for Less store in 1985 on 3rd Street in the Fairfax District which injured 23 people.[1][11][18] The Ross Dress for Less store still stands in the 6200 block of 3rd Street, on the southeast corner of Fairfax Ave. and 3rd. Overnight on March 24, 1985, methane gas filled an auxiliary room at the store and ignited, causing a spectacular explosion which blew out the windows and tore the roof off of the building, injuring 23 people, and reducing the inside to rubble. In addition to blowing up the building, the methane explosion burst out portions of the adjacent parking lot and sidewalks, venting burning gas over a wide area, creating an eerie scene with pillars of flame lighting the night. Four blocks were cordoned off by emergency crews as officials scrambled to determine what had happened.[18]

Since naturally occurring methane is odorless – utility companies add mercaptans to alert people to the presence of this flammable gas – no one had noticed the buildup of methane, so it may have accumulated to an explosive concentration slowly. The source of the methane gas was controversial; early theories involved a biogenic origin for the methane, in which it was seen as the product of decomposition of organic matter from an old swamp. In this scenario, a rising water table forced the gas from the pore spaces within the soil upwards to the surface.[18] A later theory, and the one now accepted, was that the gas originated in the oil field itself, and had migrated to the surface along a combination of the 3rd Street Fault and any number of improperly abandoned boreholes from the hundreds of now-lost wells drilled in the early years of the twentieth century. The reinjection of wastewater into the field to increase oil recovery increased the reservoir pressure to the point that gas was forced upwards along the paths of least resistance – newly formed fractures along the fault, as well as the old wellbores – until it reached the ground surface. Isotopic analysis of the near-surface methane supported this theory, as the specific isotope distributions did not match what would have been expected had the gas been recently produced by a recent biogenic mechanism, and they correlated strongly with isotopic analysis of oil field gas.[19] This finding had enormous implications for all of the urban development over old oil fields, and resulted in the construction of gas monitoring and venting wells in several locations in Los Angeles.[20] The city of Los Angeles designated approximately 400 blocks overlying the old oil field as a "High Potential Methane Zone" as a result of the 1985 explosion and subsequent investigation, and later required all structures to have a methane detector, to give warning of accumulation of the gas before it could attain explosive concentrations.[17]

1989 gas venting and evacuation

In 1989, a similar methane gas buildup occurred underneath 3rd Street and adjacent buildings, probably because of the accidental plugging of a gas-venting well built after the Ross incident.[21] Since the venting well had become clogged with a buildup of debris, methane slowly collected under the street and adjacent impermeable surfaces, bursting out on the morning of Tuesday, February 7, 1989, in a fountain of mud, water, and methane gas; no explosion occurred, since there was no source of ignition, and city emergency crews quickly cordoned off the area. As a result of this incident, Los Angeles further upgraded their City Building Code to require new buildings to have adequate venting systems, and be underlain with an impermeable membrane to prevent methane from getting in beneath the foundation.[17]

Notes

- Meehan, RL; Hamilton, DA (1992). Bernard W. Pipkin; Richard J. Proctor (eds.). "Cause of the 1985 Ross Store Explosion and Other Gas Ventings, Fairfax District, Los Angeles," Engineering geology practice in southern California. Association of Engineering Geologists. Southern California Section. pp. 145–147. ISBN 0-89863-171-8.

- Salt Lake Field query, California Department of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources

- South Salt Lake Field query, California Department of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources

- Hamilton/Meehan, p. 152

- Repetto Formation, at Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas, Austin Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Hamilton/Meehan, p. 151

- California Oil and Gas Fields, Volumes I, II and III. Vol. I (1998), Vol. II (1992), Vol. III (1982). California Department of Conservation, Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR). 1,472 pp. Salt Lake information pp. 442-447. PDF file available on CD from www.consrv.ca.gov. (As of September 2009, not available for download on their FTP site.) p. 442-446

- DOGGR, 443-444

- DOGGR, p. 446

- DOGGR, p. 447

- Landsberg, Mitchell (August 6, 2001). "Decades-Old Oil Field Dies as Fairfax Area Mall Takes Shape". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- DOGGR, p. 443

- DOGGR, p. 444

- Prutzman, Paul W. (1913). Petroleum in Southern California. Sacramento, California: California State Mining Bureau. p. 227.

- Hamilton/Meehan, pp. 146-147

- Hamilton/Meehan, p. 147

- Perera, Dave (May 10, 2001). "Fresh Produce and Streets of Fire: Making Sense of the Methane Explosion in the Fairfax". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- Lehr, Jay H.; Marve Hyman; Tyler Gass; William J. Seevers (2002). Handbook of complex environmental remediation problems. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 8.45–8.47. ISBN 0-07-027689-7.

- Hamilton/Meehan, p. 154

- Khilyuk, Leonid F.; Chilingar, George V. (2000). Gas migration: events preceding earthquakes. Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. 280–286, 389. ISBN 0-88415-430-0.

- Ramos, George; Stephen Braun (February 8, 1989). "Major Methane Gas Leak Closes Shopping Strip". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

References

- California Oil and Gas Fields, Volumes I, II and III. Vol. I (1998), Vol. II (1992), Vol. III (1982). California Department of Conservation, Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR). 1,472 pp. Salt Lake information pp. 442–447. PDF file available on CD from www.consrv.ca.gov. (As of September 2009, not available for download on their FTP site.)

- California Department of Conservation, Oil and Gas Statistics, Annual Report, December 31, 2006.

- California Department of Conservation, Oil and Gas Statistics, Annual Report, December 31, 2007.