Samuel Sanders Teulon

Samuel Sanders Teulon (2 March 1812 – 2 May 1873) was a 19th-century English Gothic Revival architect, noted for his use of polychrome brickwork and the complex planning of his buildings.

Samuel Sanders Teulon | |

|---|---|

| Born | 2 March 1812 |

| Died | 2 May 1873 (aged 61) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Architect |

Family

Teulon was born in 1812 in Greenwich, Kent, the son of a cabinet-maker from a French Huguenot family. His younger brother William Milford Teulon (1823–1900) also became an architect.

Career

He was articled to George Legg, and later worked as an assistant to the Bermondsey-based architect George Porter. He also studied in the drawing schools of the Royal Academy. He set up his own independent practice in 1838, and in 1840 won the competition to design some almshouses for the Dyers' Company at Ball's Pond, Islington. After this his practice expanded rapidly. During the next few years his works mainly consisted of parish schools, parsonages and similar buildings, mostly in the Home Counties.[2]

He was a friend of George Gilbert Scott and became a member of the Council of the Royal Institute of British Architects on 6 January 1835. Between 1841 and 1842 he undertook a long study tour of continental Europe with Ewan Christian who remained a lifelong friend and became his executor. Also in company during the tour was Horace Jones who was later knighted and became architect to the Corporation of the City of London and Hayter Lewis, later Professor of Architecture at University College, London.[3][4]

He built his first church, the Early English-style St Paul, Bermondsey, in 1846. Soon after this he designed St Stephen, Southwark, a building adapted to its square site by being planned in the form of a Greek cross, with the recessed angles filled in by the tower, vestry, chancel aisles.[2] Teulon's religious views were Low Church, and his patrons were predominantly members of established aristocratic families who shared his outlook.[5] In 1848 he received a commission from the 7th Duke of Bedford to design cottages for the Thorney estate,[6][7] and the next year he built Tortworth Court, Gloucestershire, a substantial mansion in a kind of Neo-Tudor style, with a large central tower, for the Earl of Ducie.[2] Other clients included John Sumner, archbishop of Canterbury, who commissioned Christ Church in Croydon;[2] the Duke of Marlborough, for whom he refitted the chapel at Blenheim Palace in 1857-9;[8] the 10th Duke of St Albans and Prince Albert.

His work included the remodelling of several unfashionable 18th-century churches to suit contemporary tastes. Archibald Tait, the Bishop of London, praised his alterations at St. Mary's, Ealing, as "the transformation of a Georgian monstrosity into the semblance of a Byzantine Basilica".[2]

As well as Gothic Revival churches, he designed several country houses and even complete villages, as he did at Hunstanworth in County Durham in 1863.[9]

Style

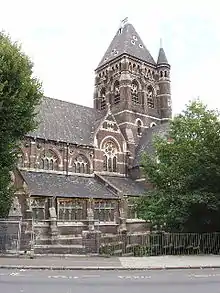

Despite his classical training, Teulon's early designs were mostly in imitation of Tudor and Elizabethan styles, and he soon became an enthusiastic follower of the latest developments of the Gothic Revival.[2] He was an enthusiastic user of Polychrome brickwork.[10] His planning was often elaborate: Henry-Russell Hitchcock called his mansion at Elvetham Park in Hampshire "so complex in its composition and so varied in its detailing that it quite defies description".[11] Some of his later work was, however, more restrained: for instance at St Stephen's Church, Rosslyn Hill, Hampstead, (1869–76) the exterior is of purple-brown brick,[12] of subtly varied tones[13] with light stone trimming. The massing of the building is also simpler than in his earlier designs.[12]

Death

For the last 20 years of his life until his death on 2nd May 1873,[2] Teulon lived in one of four Georgian mansions on Hampstead Green which were demolished at the start of the twentieth century to make way for Hampstead General Hospital, which was itself demolished in the 1970’s and replaced by The Royal Free Hospital. Opposite his home he designed St Stephen's Church, Rosslyn Hill. He was buried in Highgate Cemetery[14] not far from the family vault of his former neighbour on Hampstead Green, Rowland Hill.

His great great great nephew, Alan Teulon, published a book on S.S. Teulon in 2009.[15] He was survived by four sons and four daughters.[2]

Works

.jpg.webp)

- St James's Vicarage, Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire; additional wing 1844 (now demolished)[16]

- St Mary's Rectory, North Creake, Norfolk; 1845[17]

- Holkham Hall, Norfolk, porch 1847[18]

- St Paul's Parish Church, Bermondsey; 1848 (demolished 1961)[19]

- All Saints' Parish Church, Icklesham, East Sussex; restoration 1848–49[20]

- Church of the Holy Spirit, Rye Harbour, East Sussex; 1848–49[21]

- Owlpen House, Owlpen, Gloucestershire; 1848 (demolished 1955-6, apart from the stables and lodge)[22]

- Thorney Model Village, Cambridgeshire; from 1848[6][7]

- St Mary's Parish Church, Pakenham, Suffolk; alterations 1849[23]

- Queen's Terrace, Windsor, Berkshire; 1849[24]

- St Paul's Church, Sandgate, Kent; 1849[25]

- St Peter's Church, Great Birch, Essex; 1849–50[26]

- Tortworth Court, Tortworth, Gloucestershire; 1849–52[27]

- St John's Parish Church, Rushford, Norfolk; restoration c.1850[28]

- St Mary's Parish Church, Benwick, Cambridgeshire; 1850 (now demolished)[29]

- St Mary's Parsonage, Grendon, Northamptonshire; 1850[30]

- St Mary's Church, Riseholme, Lincolnshire 1851[31]

- St John's Parish Church, Kingscote, Gloucestershire; restoration 1851[32]

- Christ Church, Croydon, Surrey; 1851–1852 (largely destroyed 1985)[33]

- Holy Trinity Parish Church, Hastings, East Sussex; rebuilding 1851–59[34]

- St Andrew's Parish Church, Brettenham, Norfolk; restorations and remodelling 1852 [35]

- St James' Church, Edgbaston, Birmingham; 1852[36]

- St Margaret's Parish Church, Angmering, West Sussex; restoration 1852–53[37]

- St John's Church, Ladywood, Birmingham; 1852–54[38]

- Estate cottages, Windsor, Berkshire; 1853[39]

- School in Oxford Road, Woodstock, Oxfordshire; 1854[40]

- A cottage, Tortworth, Gloucestershire; 1854[41]

- Sandringham House, Norfolk, porch and conservatory 1854[42]

- Cholmondeley Castle, Cheshire; alterations 1854[43]

- Schoolmaster's house and chapel, Curridge, Berkshire; 1854–55[44]

- Christ Church Parish Church, Fosbury, Wiltshire; 1854–56[45]

- St Andrew's Parish Church, Lambeth, London; 1855[46]

- St Mary's Vicarage, Steeple Barton, Oxfordshire; 1856[47]

- St John the Baptist's Parish Church, Burringham, Lincolnshire; 1856–57[48]

- Gisborough Hall, Guisborough, North Yorkshire; 1857 (also attributed to William Milford Teulon)[49]

- St Mary's Parish Church, Sunbury, Surrey; internal alterations 1857[50]

- St Thomas's Church, Pearman Street, Lambeth; 1857 (demolished)[51]

- Shadwell Park, Rushford, Norfolk; extensions & remodelling 1857–60[52]

- All Saints' Parish Church, Wordwell, Suffolk; restoration 1857 and 1866[53][54]

- St Giles's Parish Church, Uley, Gloucestershire; rebuilding 1857–58[55]

- St Mary's Parish Church, Alderbury, Wiltshire; 1857–58[56]

- Holy Trinity Parish Church, Oare, Wiltshire; 1857–58[57] - Pevsner considered it "the ugliest church in Wiltshire".[58]

- All Saints' Parish Church, Middleton Stoney, Oxfordshire; rebuilding 1858[59]

- St Bartholomew's Parish Church, Newington Bagpath, Gloucestershire; rebuilt chancel 1858[60]

- Browne's Charity Almshouses and Chapel, South Weald, Essex 1858[61][62]

- St James's Parish Church, Leckhampstead, Berkshire; 1858–60[63]

- Prince Albert's Workshops, Windsor Great Park, Berkshire; 1858–61[39]

- St Stephen's Parish Church, Manciple Street, Southwark; 1859 (demolished 1965)[64]

- St John the Baptist's Parish Church, Netherfield, East Sussex; 1859[65]

- Christ Church, Wimbledon, London; 1859–60[66]

- Elvetham Hall, Elvetham, Hampshire; 1859–60[67]

- Hawkleyhurst House, Hawkley, Hampshire; 1860[68]

- St Mary's Vicarage, Gainford, County Durham; 1860

- St Silas' Church, Penton Street, Islington; 1860, completed 1863 by E.P. Loftus Brock[69]

- St Bartholomew's Parish Church, Nympsfield, Gloucestershire; rebuilt church 1861–63[70]

- St Mark's Parish Church, Silvertown, London; 1861–62[71] (now the Brick Lane Music Hall)

- Huntley Manor, Huntley, Gloucestershire; 1862[72]

- Bestwood Lodge, Bestwood, Nottinghamshire; 1862–65[73]

- St John the Baptist's Parish Church, Huntley, Gloucestershire; 1863[74]

- Village of Hunstanworth, County Durham; 1863[9]

- St Thomas's Parish Church, Camden, London; 1863 (now demolished)[75]

- All Saints Church, Benhilton, Sutton, London; 1863[76]

- St Mary's Parish Church, Woodchester, Gloucestershire; 1863–64[77]

- Royal Chapel of All Saints, Windsor Great Park, Berkshire; 1863–66[78]

- St Peter and St Paul's Parish Church, Hawkley, Hampshire; 1865[68]

- St Mary's Parish Church, Horsham, Sussex; south aisle 1865[79]

- Wrotham Park, Hertfordshire; alterations 1865[80]

- St George's Parish Church, Hanworth, Middlesex; spire 1865[81]

- Buxton Memorial Fountain in Victoria Tower Gardens, London; 1865[82]

- Tyndale Monument, North Nibley, Gloucestershire; 1866[83]

- St Paul's Parish Church, Greenwich; 1866[84]

- St Margaret's Parish Church, Hopton-on-Sea, Norfolk; 1866-7[85]

- St Mary's Parish Church, Ealing, London; 1866–73[86]

- St Andrew's and St John's School, Roupell Street, Lambeth; c.1868[87]

- Lychgate to Church of St. Peter, South Weald, Essex 1868[88][62]

- Church of St. Peter, South Weald, Essex 1868[89][62]

- St Stephen's Parish Church, Rosslyn Hill, Hampstead, London; 1869-71[90]

- The Court House, St Andrew Holborn, London; 1870[91]

- St John the Baptist's Parish Church, Windsor, Berkshire; alterations 1869–73[92]

- Woodlands Vale House, Ryde, Isle of Wight; 1870–71[93]

- St Frideswide's Parish Church, New Osney, Oxford; 1870–72[94]

- Holy Trinity Parish Church, Leicester; remodelling 1871[95]

- St Andrew's Parish Church, Eastern Green, Coventry; 1875[96]

- Embrook House, Sandgate, Kent; 1852 (demolished)[25][97]

- Riseholme Hall, Stable block (perhaps) Riseholme, Lincolnshire 1840–45[31]

References

- https://www.londonremembers.com/subjects/samuel-sanders-teulon accessed 20 July 2017

- "Samuel Sanders Teulon, Fellow.". Papers Read at the Royal Institute of British Architects, Session 1872–73. 1873. pp. 215–7.

- Brown 1985, pp. 133–134.

- Brodie 2001, p. 779.

- Jones, Nigel R. (2005). Architecture of England, Scotland, and Wales. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780313318504.

- http://www.fensmuseums.org.uk/page_id__30.aspx accessed 20 July 2017

- http://www.thorney-museum.org.uk/19th-century accessed 20 July 2017

- Crossley, Alan and Elrington, ed. (1990). "Blenheim: Blenheim Palace". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 12: Wootton Hundred (South) including Woodstock. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Pevsner 1953, p. 172.

- Hitchcock1977, p. 250.

- Hitchcock1977, p. 256.

- Hitchcock1977, p. 269.

- Eastlake, p. 368.

- source: Miscellanea Geneaologica et Heraldica, 4 Series Vol II (1909) as noted in Alan Teulon's The Life and Work of Samuel Sanders Teulon (2009)

- "Famous ancestor built chapel for royal family". www.northamptonchron.co.uk.

- Verey 1970, vol. 1, p. 156.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1152693)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- http://www.parksandgardens.org/places-and-people/site/1766/history accessed 20 July 2017

- "Bermondsey, St. Paul" (PDF). Diocese of Southwark. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 543.

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 600.

- Nicholas Mander, Owlpen Manor, Gloucestershire: a short history and guide to a romantic Tudor manor house in the Cotswolds. (current edition: 2006). OCLC 57576417.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1181353)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 304.

- "Conservation Area Appraisal Sandgate" (PDF). Shepway District Council. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Janet Cooper (Editor) (2001). "Birch: Churches". A History of the County of Essex: Volume 10: Lexden Hundred (Part) including Dedham, Earls Colne and Wivenhoe. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 5 May 2012.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Verey 1970, vol. 2, p. 389.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1076907)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Cambridgeshire, p302, (Second edition) By Nikolaus Pevsner

- Pevsner & Cherry 1973, p. 241.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1964). Buildings of England: Lincolnshire. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 343.

- Verey 1970, vol. 1, p. 286.

- http://southwark.anglican.org/downloads/lostchurches/CRO03.pdf accessed 20 July 2017

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 522.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/services-skills/grants/visit/st-andrew-brettenham-ip24-2rp/ accessed 20 July 2017

- Pevsner & Wedgwood 1966, p. 165.

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, pp. 52, 53.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 137.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 296.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 857.

- Verey 1970, vol. 2, p. 390.

- http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF3272-Sandringham-House&Index=3025&RecordCount=57339&SessionID=01e7beea-f6b9-44e1-b332-4997fe6213e5 accessed 20 July 2017

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1000638)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 126.

- Pevsner & Cherry 1975, p. 250.

- http://southwark.anglican.org/downloads/lostchurches/LAM05.pdf accessed 20 July 2017

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 788.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1083016)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Historic England, "Gisborough Hall, and retaining wall, balustrade, piers and steps to the south (1310795)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 17 November 2017

- https://historicengland.org.uk/services-skills/grants/visit/st-mary-church-street-tw16-6rg/ accessed 20 July 2017

- "Lambeth, St Thomas" (PDF). Diocese of Southwark. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1001019)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- http://www.suffolkchurches.co.uk/wordwell.htm accessed 20 July 2017

- http://www.crsbi.ac.uk/site/369/ accessed 20 July 2017

- Verey 1970, vol. 1, pp. 459–460.

- Pevsner & Cherry 1975, p. 83.

- Pevsner & Cherry 1975, p. 363.

- Bradley & Cherry 2001, p. 108.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 701.

- Verey 1970, vol. 1, p. 332.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1197264)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Pevsner 1954, pp. 421–422.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 166.

- "Southwark, St Stephen" (PDF). Diocese of Southwark. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 570.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1193071)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Pevsner & Lloyd 1967, pp. 210–211.

- Pevsner & Lloyd 1967, p. 280.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1208241)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Verey 1970, vol. 1, p. 347.

- "St Marks". Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Verey 1970, vol. 2, p. 275.

- Pevsner 1951, p. 35.

- Verey 1970, vol. 2, p. 274.

- https://search.lma.gov.uk/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/LMA_OPAC/web_detail/REFD+P90~2FTMS?SESSIONSEARCH accessed 20 July 2017

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Verey 1970, vol. 1, p. 485.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 297.

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 243.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1000254)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "St George's Hanworth - History". St George's Hanworth. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1066151)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Verey 1970, vol. 1, p. 344.

- "Greenwich, St Paul" (PDF). Diocese of Southwark. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1050972)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1079376)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1064981)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1208633)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1297216)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/services-skills/grants/visit/st-stephen-pond-street-nw3-2pp/ accessed 20 July 2017

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1079152)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Pevsner 1966, p. 298.

- Pevsner & Lloyd 1967, p. 766.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 334.

- Pevsner & 19, p. 149.

- Pevsner & Wedgwood 1966, p. 288.

- http://www.folkestonehistory.org/uploads/53%20Win%202012.pdf accessed 20 July 2017

Sources

- Brodie, Antonia; Felstead, Alison; Franklin, Jonathan; Pinfield, Leslie; Oldfield, Jane, eds. (2001). Directory of British Architects 1834–1914, L–Z. London & New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-5514-X.

- Eastlake, Charles Locke (1872). A History of the Gothic Revival. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Hitchcock, Henry-Russell (1977). Architecture:Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. The Pelican History of Art. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-056115-3.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). Sussex. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1951). Nottinghamshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1953). County Durham. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1954). Essex. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1960). Leicestershire and Rutland. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1966). Berkshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (1973) [1961]. Northamptonshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071022-1.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (revision) (1975) [1963]. Wiltshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071026-4.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Lloyd, David (1967). Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Wedgwood, Alexandra (1966). Warwickshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Saunders, Matthew, ed. (1982). The churches of S. S. Teulon. London: The Ecclesiological Society.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

- Teulon, A.E (2009). The Life and Work of Samuel Sanders Teulon: Victorian Architect. http://www.northamptonchron.co.uk/community/nostalgia/famous_ancestor_built_chapel_for_royal_family_1_3288582 self-published book by historian and great-great-great nephew of S.S. Teulon

- Verey, David (1970). Gloucestershire: The Cotswolds. The Buildings of England. 1. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071040-X.

- Verey, David (1970). Gloucestershire: The Vale and the Forest of Dean. The Buildings of England. 2. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Brown, Roderick, ed. (1985). The Architectural Outsiders (chapter by Matthew Saunders). London: Waterstone. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0947752048.

- Simon Bradley; Bridget Cherry, eds. (2001). The Buildings of England: A Celebration. Cambridge: Penguin Collectors' Society. ISBN 0952740133.

- Worsley, Giles (December 2001). "Master builder Samuel Sanders Teulon 1812–73". Daily Telegraph.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samuel Sanders Teulon. |