Seasteading

Seasteading is the concept of creating permanent dwellings at sea, called seasteads, outside the territory claimed by any government. The term is a blend of sea and homesteading.

| Part of a series on |

| Living spaces |

|---|

|

Proponents say seasteads can "provide the means for rapid innovation in voluntary governance and reverse environmental damage to our oceans ... and foster entrepreneurship." [1] Some critics fear seasteads are designed more as a refuge for the wealthy to avoid taxes or other obligations.[2]

No one has yet created a structure on the high seas that has been recognized as a sovereign state. Proposed structures have included modified cruise ships, refitted oil platforms, and custom-built floating islands.[3]

As an intermediate step, the Seasteading Institute has promoted cooperation with an existing nation on prototype floating islands with legal semi-autonomy within the nation's protected territorial waters. On January 13, 2017, the Seasteading Institute signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with French Polynesia to create the first semi-autonomous "seazone" for a prototype,[4][5] but later that year political changes driven by the French Polynesia presidential election led to the indefinite postponement of the project.[6] French Polynesia formally backed out of the project and permanently cut ties with Seasteading on March 14, 2018.[7]

The first single-family seastead was launched near Phuket, Thailand by Ocean Builders.[8] Two months later, the Thai Navy claimed the seastead was a threat to Thai sovereignty.[9] As of 2019, Ocean Builders says it will be building again in Panama, with the support of government officials.[10]

At least two people independently coined the term seasteading: Ken Neumeyer in his book Sailing the Farm (1981) and Wayne Gramlich in his article "Seasteading – Homesteading on the High Seas" (1998).[11]

History

Many architects and firms have created designs for floating cities, including Vincent Callebaut,[12][13] Paolo Soleri[14] and companies such as Shimizu, Ocean Builders[15] and E. Kevin Schopfer.[16]

For a dozen years L. Ron Hubbard, founder of the Church of Scientology, and his executive leadership became a maritime-based community named the Sea Organization (Sea Org). Beginning in 1967 with a complement of four ships, the Sea Org spent most of its existence on the high seas, visiting ports around the world for refueling and resupply. In 1975 much of these operations were shifted to land-based locations.

Marshall Savage discussed building tethered artificial islands in his 1992 book The Millennial Project: Colonizing the Galaxy in Eight Easy Steps, with several color plates illustrating his ideas.

Other historical predecessors and inspirations for seasteading include:

- Oil platforms.

- The Principality of Sealand, a micronation formed on a decommissioned sea fort near Suffolk, England.[17]

- Smaller floating islands in protected waters, such as Richart Sowa's Spiral Island

- Floating communities, such as the Uru people on Lake Titicaca, the Tanka people in Aberdeen, Hong Kong, and the Makoko in Lagos, Nigeria.

- The non-profit Women on Waves, which operates hospital ships that allow access to abortions for women in countries where abortions are subject to strict laws

- The Republic of Rose Island, a short-lived micronation on a man-made platform in the Adriatic Sea, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) off the coast of the province of Rimini, Italy.

- Pirate radio stations anchored in international waters, broadcasting to listeners on shore.

Gramlich's essay attracted the attention of Patri Friedman.[18] The two began working together and posted their first collaborative book online in 2001.[19] Their book explored many aspects of seasteading from waste disposal to flags of convenience. This collaboration led to the creation of the non-profit The Seasteading Institute (TSI) in 2008.

In March 2019, a group called Ocean Builders claimed to have built the first seastead in International Waters, off the coast of the Thai island of Phuket.[20] Thai Navy officials have charged them of violating Thai Sovereignty.[21]

In April 2019, the concept of floating cities as a way to cope with rising oceans was included in a presentation by the United Nations program UN-Habitat. As presented, they would be limited to sheltered waters.[22]

The Seasteading Institute

On April 15, 2008, Wayne Gramlich and Patri Friedman founded the 501(c)(3) non-profit The Seasteading Institute (TSI), an organization formed to facilitate the establishment of autonomous, mobile communities on seaborne platforms operating in international waters.[23][24][25]

Friedman and Gramlich noted that according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a country's Exclusive Economic Zone extends 200 nautical miles (370 km) from shore. Beyond that boundary lie the high seas, which are not subject to the laws of any sovereign state other than the flag under which a ship sails. They proposed that a seastead could take advantage of the absence of laws and regulations outside the sovereignty of nations to experiment with new governance systems, and allow the citizens of existing governments to exit more easily.[23][26][27]

The project picked up mainstream exposure after PayPal cofounder Peter Thiel donated $500,000 in initial seed capital[26] (followed by subsequent contributions). He also spoke out on behalf of its viability in his essay "The Education of a Libertarian".[28] TSI received widespread media attention.[29][25][30][31][32]

In 2008, Friedman and Gramlich said they hoped to float the first prototype seastead in the San Francisco Bay by 2010[33][34] followed by a seastead in 2014.[35] TSI did not meet these targets.

In January 2009, the Seasteading Institute patented a design for a 200-person resort seastead, ClubStead, about a city block in size, produced by consultancy firm Marine Innovation & Technology. The ClubStead design marked the first major engineering analysis in the seasteading movement.[25][36][37]

In July 2012, the vessel Opus Casino was donated to the Seasteading Institute.[38]

The Floating City Project

In the spring of 2013,[39] TSI launched The Floating City Project.[40] The project proposed to locate a floating city within the territorial waters of an existing nation, rather than the open ocean.[41] TSI claimed that doing so would have several advantages by placing it within the international legal framework and making it easier to engineer and easier for people and equipment to reach.

In October 2013, the Institute raised $27,082 from 291 funders in a crowdfunding campaign[42] TSI used the funds to hire the Dutch marine engineering firm DeltaSync[43] to write an engineering study for The Floating City Project.

In September 2016 the Seasteading Institute met with officials in French Polynesia[44] to discuss building a prototype seastead in a sheltered lagoon.[45] On January 13, 2017, French Polynesia Minister of Housing Jean-Christophe Bouissou signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with TSI to create the first semi-autonomous "seazone". TSI spun off a for-profit company called "Blue Frontiers", which will build and operate a prototype seastead in the zone.[46]

On March 3, 2018, French Polynesia government said the agreement was "not a legal document" and had expired at the end of 2017.[47] No action has been announced since.

Other projects

Jounieh Floating Island project (JFIP)

A proposal to build a "floating island" with a luxury hotel in Jounieh north of the Lebanese capital Beirut, was stalled as of 2015 because of concerns from local officials about environmental and regulatory matters.[48][49]

Blueseed

Blueseed was a company aiming to float a ship near Silicon Valley to serve as a visa-free startup community and entrepreneurial incubator. Blueseed founders Max Marty and Dario Mutabdzija met when both were employees of The Seasteading Institute. The project planned to offer living and office space, high-speed Internet connectivity, and regular ferry service to the mainland[50][51] but as of 2014 the project was "on hold".[52]

Design proposals

Cruise ships

Cruise ships are a proven technology, and address most of the challenges of living at sea for extended periods of time. However, they're typically optimized for travel and short-term stay, not for permanent residence in a single location.

Examples:

- Satoshi (ship)

- Blue Seed retro-fitted cruise ship.[51]

- Freedom Ship[53]

- MS Satoshi[54]

Spar platform

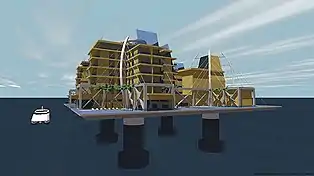

Platform designs based on spar buoys, similar to oil platforms.[55] In this design, the platforms rest on spars in the shape of floating dumbbells, with the living area high above sea level. Building on spars in this fashion reduces the influence of wave action on the structure.[36]

Examples:

Modular island

There are numerous seastead designs based around interlocking modules made of reinforced concrete.[58] Reinforced concrete is used for floating docks, oil platforms, dams, and other marine structures.

Examples:

Monolithic island

A single, monolithic structure that is not intended to be expanded or connected to other modules.

Examples:

- Evolo Seascraper[62]

- SeaOrbiter[63] proposed oceangoing research vessel.

Criticism

Criticisms have been leveled at both the practicality and desirability of seasteading.

Critics believe that creating governance structures from scratch is a lot harder than it seems.[64] Also, seasteads would still be at risk of political interference from nation states.[25]

On a logistical level, without access to culture, travel, restaurants, shopping, and other amenities, seasteads could be too remote and too uncomfortable to be attractive to potential long-term residents.[25] Building seasteads to withstand the rigors of the open ocean may prove uneconomical.[64][25]

Seastead structures may blight ocean views, their industry or farming may deplete their environments, and their waste may pollute surrounding waters. Some critics believe that seasteads will exploit both residents and the nearby population.[64] Others fear that seasteads will mainly allow wealthy individuals to escape taxes,[2] or to harm mainstream society by ignoring other financial, environmental, and labor regulations.[2][64]

Conferences

The Seasteading Institute held its first conference in Burlingame, California, October 10, 2008. Forty-five people from nine countries attended.[65] The second Seasteading conference was significantly larger, and held in San Francisco, California, September 28–30, 2009.[66][67] The third Seasteading conference took place May 31 – June 2, 2012.[68]

In popular culture

Seasteading has been imagined many times in novels as early as Jules Verne's 1895 science-fiction book Propeller Island (L'Île à hélice) about an artificial island designed to travel the waters of the Pacific Ocean, and as recent as 2003's The Scar, which featured a floating city, Armada. It has been a central concept in some movies, notably Waterworld (1995) and in TV series such as Stargate Atlantis, which had a complete floating city. It is a common setting in video games, forming the premise of BioShock and BioShock 2, Brink, and Call of Duty: Black Ops II; and in anime, such as Gargantia on the Verdurous Planet which takes place mainly on a traveling city made of an interconnected fleet of ocean ships.

See also

References

- Seasteading.org: Why Steastead?

- Wong, Julia Carrie (January 2, 2017). "Seasteading: tech leaders' plans for floating city trouble French Polynesians" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Mangu-Ward, Katherine (April 28, 2008). "Homesteading on the High Seas: Floating Burning Man, "jurisdictional arbitrage," and other adventures in anarchism". Reason Magazine. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- Carli, James (December 10, 2016). "Oceantop Living in a Seastead - Realistic, Sustainable, and Coming Soon". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- BBC, News (January 17, 2017). "French Polynesia signs first floating city deal". BBC. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- "The Seasteading Institute Projects". seasteading.org. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- Robinson, Melia. "An island nation that told a libertarian 'seasteading' group it could build a floating city has pulled out of the deal". Business Insider. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "First Seastead in International Waters Now Occupied, Thanks to Bitcoin Wealth". Reason.com. 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- Hunter, Brittany (2019-05-08). "The World's First Seasteaders Are Now on the Run for Their Lives | Brittany Hunter". fee.org. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- "Ocean Builders moves forward". Ocean Builders.

- "SeaSteading -- Homesteading the High Seas". gramlich.net.

- "Vincent Callebaut Architecte LILYPAD". callebaut.org.

- "LILYPAD feature". archinect.com.

- Rose, Steve (August 25, 2008). "The man who saw the future". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- "Ocean Builders". Ocean Builders.

- "12 Post-Apocalypse Floating Cities and Homes: From Crazy Concepts to Reality". TreeHugger.

- "Explorers in the Valley still charting new territory". The Irish Times. 19 September 2008.

- Fingleton, Eamonn (March 26, 2010). "Seasteading: the great escape". Prospect Magazine. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- Gramlich, Wayne; Friedman, Patri (2002). "Getting Serious About SeaSteading". Andrew House. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- seasteading (2019-03-08), THE FIRST SEASTEADERS 4: Living the Life, retrieved 2019-04-21

- "Seasteading couple charged as Thai navy boards floating home". ABC News. 2019-04-21. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- National Geographic: "Floating cities could ease global housing crunch, says UN"

- Baker, Chris (January 19, 2009). "Live Free or Drown: Floating Utopias on the Cheap". Wired Magazine. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- "History".

- "Cities on the Ocean". The Economist. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "Peter Thiel Makes Down Payment on Libertarian Ocean Colonies". Wired. 18 May 2008.

- "City floating on the sea could be just 3 years away". CNN. March 3, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- Peter Thiel (April 13, 2009). "The Education of a Libertarian".

- "Seasteading: the great escape". Prospect Magazine. April 2010.

- "Seasteading Misconceptions - Business Insider". Business Insider. 16 November 2013.

- "BBC - Future - Ocean living: A step closer to reality?". BBC Future.

- Stossel, John (11 February 2011). "Is Seasteading the Future?".

- Adam Frucci. "Silicon Valley Nerds Plan Sea-Based Utopian Country to Call Their Own". Gizmodo. Gawker Media.

- "Libertarian Island: No Rules, Just Rich Dudes". NPR.org. 21 May 2008.

- "Seasteading: A Possible Timeline". Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- Gramlich, Wayne; Friedman, Patri; Houser, Andrew (2002–2004). "Seasteading". seasteading.org. Archived from the original on 2009-02-10. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- "ClubStead". seasteading.org. 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- Hencken, Randolph (2012-08-26). "The Seasteading Institute Acquires Seasteader I, a 275-foot Ship". The Seasteading Institute August 2012 Newsletter. The Seasteading Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05.

- Charlie Deist. "The Seasteading Institute".

- "Floating City Project - The Seasteading Institute - Startup Cities". The Seasteading Institute.

- "Start". Startup Cities Institute.

- "Designing the Worlds First Floating City - Indiegogo". Indiegogo.

- "DeltaSync". deltasync.nl.

- https://www.seasteading.org/2016/09/french-polynesia-open-seasteading-collaboration/

- "Government of French Polynesia Signs Agreement with Seasteaders for Floating Island Project | The Seasteading Institute". www.seasteading.org. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- Megson, Kim (2017-01-24). "French Polynesia could host world's first floating city after signing agreement with Seasteading Institute". CLADnews. Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- "French Polynesia sinks floating island project". Radio New Zealand. February 28, 2018.

- Middle East Eye: "Authorities block floating island"

- Report about project on MTV Lebanon television (in Arabic)

- Lee, Timothy (2011-11-29). "Startup hopes to hack the immigration system with a floating incubator". Ars Technica. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Donald, Brooke (16 December 2011). "Blueseed Startup Sees Entrepreneur-Ship as Visa Solution for Silicon Valley". Huffington Post. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- "Blueseed - Lessons learned four years later". October 26, 2015.

- "World's first floating city back on course". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- "Live, Work and Play on a Residential Cruise Ship". PRWeb. Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- McCullagh, Declan (February 2, 2009). "Next Frontier: "Seasteading" The Oceans". CBS News. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- "Oil Platforms Transformed into Sustainable Seascrapers- eVolo - Architecture Magazine". evolo.us.

- "SeaPod | Ocean Builders". Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- "Apply Seasteading Concrete Shell Structures - The Seasteading Institute". The Seasteading Institute. Archived from the original on 2010-07-10.

- "Floating City Project | The Seasteading Institute". www.seasteading.org. 17 December 2015. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- "Oceanscraper- eVolo - Architecture Magazine". evolo.us.

- "Floating City concept by AT Design Office features underwater roads". Dezeen. 13 May 2014.

- "Seascraper – Floating City - eVolo - Architecture Magazine". evolo.us.

- Raj, Ajai (2014-06-14). "A SPACESHIP FOR THE SEA". Popular Science. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

- Denuccio, Kyle. "Silicon Valley Is Letting Go of Its Techie Island Fantasies". WIRED. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- "Seasteading Institute 2008 Annual Report" (PDF). TSI. April 15, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- "Seasteading 2009 Annual Conference". TSI. August 10, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- McCullagh, Declan (2009-10-11). "Seasteaders Take First Step Toward Colonizing The Oceans". CBSNews. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- Wilkey, Robin (June 4, 2012). "Seasteading Institute Convenes In San Francisco: Group Fights For Floating Cities (PHOTOS)" – via Huff Post.

External links

| Look up seasteading in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |