Septemberprogramm

The Septemberprogramm (German: [zɛpˈtɛmbɐpʁoˌɡʁam], literally "September Program") was the plan for the territorial expansion of the German Empire, prepared for Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, at the beginning of World War I (1914–18). The Chancellor's private secretary, Kurt Riezler, drafted the Septemberprogramm on 9 September 1914, in the early days of the German attack in the west, when Germany expected to defeat France quickly and decisively. The extensive territorial conquests proposed in the Septemberprogramm included making a vassal state of Belgium, annexing portions of France, expanding its colonies in Africa, and seizing much of the Russian Empire. The Septemberprogramm was not effected because France withstood the initial German attack, the war devolved into a trench-warfare stalemate, and ultimately ended in German defeat.[1]

As geopolitics, the Septemberprogramm itself is a documentary insight to Imperial Germany's war aims, and shows the true scope of German plans for territorial expansion in two directions, east and west. Historian Fritz Fischer wrote that the Septemberprogramm was based on the Lebensraum philosophy, which made territorial expansion Imperial Germany's primary motive for war.[2] Jonathan Steinberg has suggested that if the Schlieffen Plan had worked, and produced a decisive German victory, like the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the Septemberprogramm would have been implemented, thus establishing German hegemony in Europe.[3]

War goals

The Septemberprogramm was a list of goals for Germany to achieve in the war:[4][5]

- France should cede some northern territory, such as the iron-ore mines at Briey and a coastal strip running from Dunkirk to Boulogne-sur-Mer, to Belgium or Germany.

- France should pay a war indemnity of 10 billion German Marks, with further payments to cover veterans' funds and to pay off all of Germany's existing national debt. This would prevent French rearmament for the next couple decades, make the French economy dependent on Germany, and end trade between France and the British Empire.

- France will partially disarm by demolishing its northern forts.

- Belgium should be annexed to Germany or, preferably, become a vassal state, which should cede eastern parts and possibly Antwerp to Germany and give Germany military and naval bases.

- Luxembourg should become a member state of the German Empire.

- Buffer states would be created in territory carved out of the western Russian Empire, such as Poland, which would remain under German sovereignty.[4]

- Germany would create a Mitteleuropa economic association, ostensibly egalitarian but actually dominated by Germany. Members would be France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria-Hungary, the new buffer states, and possibly Italy, Sweden, and Norway.[6]

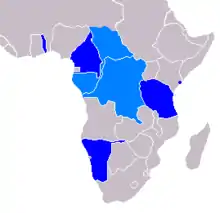

- The German colonial empire would be expanded. The German possessions in Africa would be enlarged to create a contiguous German colony across central Africa (Mittelafrika) at the expense of the French and Belgian colonies. Presumably to leave open future negotiations with Britain, no British colonies were to be taken, but Britain's "intolerable hegemony" in world affairs was to end.

- The Netherlands should be brought into a closer relationship to Germany while avoiding any appearance of coercion.

Significance

The Septemberprogramm was based on suggestions from Germany's industrial, military, and political leadership.[7][8] However, since Germany did not win the war, it was never put into effect. As historian Raffael Scheck concluded, "The government, finally, never committed itself to anything. It had ordered the Septemberprogramm as an informal hearing in order to learn about the opinion of the economic and military elites."[9]

In the east, on the other hand, Germany and her allies did demand and achieve significant territorial and economic concessions from Russia in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and from Romania in the Treaty of Bucharest.[8]

References

- Edgar Feuchtwanger (2002). Imperial Germany 1850–1918. Routledge. pp. 178–79. ISBN 9781134620739.

- Fischer, Fritz (1967). Germany's Aims in the First World War.

- Steinberg, Jonathan (April 2013). "Old Knowledge and New Research: A Summary of the Conference on the Fischer Controversy 50 Years On". Journal of Contemporary History. 48 (2). quotation in p. 249.

- Tuchman, Barbara (1962). The Guns of August. New York, New York: Macmillan Co. p. 321.

- "Bethmann Hollweg, Germany's War Aims". wwnorton.com. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- "Deutsch-Französische Materialien: Kriegsziele Deutschlands". www.deuframat.de. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (1980). In the Eye of the Storm: Kurt Riezler and the Crises of Modern Germany. pp. 98–99.

- Scheck, Raffael. "Military Operations and Plans for German Domination of Europe". Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- See Raffael Scheck, Germany 1871–1945: A Concise History (2008)

Further reading

- Thompson, Wayne C. (1978). "The September Program: Reflections on the Evidence". Central European History. 11 (4): 348–354. doi:10.1017/S0008938900018823.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (1980). In the Eye of the Storm: Kurt Riezler and the Crises of Modern Germany. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 978-0-87745-094-8.

External links

- (in German) Full text of the Septemberprogramm. 9 September 1914. Retrieved on 2010-09-15.

- (in German) Full text of the Septemberprogramm (DeuFraMat = Deutsch-französische Materialien für den Geschichts- und Geographieunterricht (German-French Materials for Historical and Geographic Education))

- (in English) English Translation. Retrieved on 2010-09-15.