Sergei Tokarev

Sergei Aleksandrovich Tokarev (Russian: Серге́й Алекса́ндрович То́карев, 29 December 1899 – 19 April 1985) was a Russian scholar, ethnographer, historian, researcher of religious beliefs, doctor of historical sciences, and professor at Moscow State University.

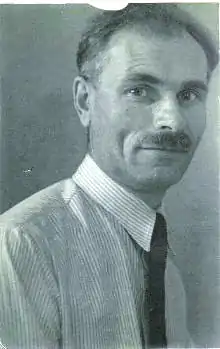

Sergei Aleksandrovich Tokarev | |

|---|---|

Tokarev in 1960 | |

| Born | Серге́й Алекса́ндрович То́карев 29 December 1899 |

| Died | 19 April 1985 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation | Ethnologist |

Birth and education

Sergei Aleksandrovich Tokarev was born in Tula on 29 December 1899.[1] He graduated with honors from Tula grammar school and entered Moscow University. Immediately after the revolution, conditions in Moscow in 1918 were dangerous and difficult, and Tokarev went back to the apparent safety of his home province of Tula. He taught Russian and Latin in local schools for four years. Tokarev returned to Moscow University in 1922, where he began social and historical studies. He received a state scholarship, and supplemented his income by giving private lessons. In 1924 he obtained a job as a bibliographer at the Central Library.[2]

After graduating on 25 June 1925, Tokarev applied to continue research in the university's graduate Institute of History. He submitted a thesis on "totemic society", a fully-fledged work of research. His application was supported by a short but very flattering recommendation from Viacheslav Petrovich Volgin. Accepted in November 1925, Tokarev was enrolled in the Institute in January 1926, joining what later became the ethnology section.[3]

In the spring of 1926 Tokarev presented a report on Australian totemism. In the 1926/1927 academic year he prepared a report on Melanesian religions and gave a talk on Australian kinship systems. In June 1927 Tokarev presented a report on the economic structure of English Manors in the 13th to 15th centuries. In 1927/1928 Tokarev returned to the Melanesian theme with a report on the social system of these people. His post-graduate training was completed in 1929, although officially he did not graduate until 1 January 1930.[4]

Early career

Tokarev began working at the Central Museum of Ethnology in October 1927. In 1928, he joined the department of colonies at the museum, and in 1931 he was appointed head of the department of North Asia. As a graduate student, in 1928/1929 he also taught part-time at Moscow University, and taught a course on the history of social structures at the Sun Yat-sen University of Communist Workers of China.[5]

Ethnography was considered important in the early years of the Soviet Union, which had a great many different ethnic groups, and the first university courses for professional ethnography were launched in the 1920s. However, by the latter part of the decade, Marxist radicals attacked the discipline for being "bourgeois", and some of the main ethnographic institutions were closed in April 1929. Ethnography became redefined as the study of prehistoric peoples.[6] The University's Institute of History became part of the Communist Academy. Most positions went only to Marxists and communists, although in some circumstances non-Marxist scholars could be admitted.[7]

The Marxist linguist Valerian Borisovich Aptekar[lower-alpha 1] was an opponent of traditional ethnography, strongly expressing his opinion in a debate on 7 May 1928. He argued that the subject was not scientific, that its concepts were vague, and that by treating the development of mankind in terms of the evolution of cultural forms the ethnographers denied the more fundamental forces of production and class struggle. The subject could only be approached in terms of dialectical materialism.[9] Tokarev disagreed publicly. Although he accepted the need for a more scientific approach and for the subject to be treated from a Marxist–Leninist viewpoint, he defended the study of ethnology as dealing with realities that could not be ignored.[10] Further debates were held at meetings of the AMI in April 1929 and in June 1930.[11] Tokarev was still working at the museum, and the authorities frowned on people holding two positions. He was dismissed from the institute on 1 May 1931 but continued as a free-lance researcher and retained the more secure job at the Museum.[7]

Despite the political climate, Tokarev undertook valuable work in the late 1920s and the 1930s.[6] He spent less time on Australia and Melanesia and more time on the people of Siberia and Yakutia, perhaps due to political pressure, although he was always interested in both subjects.[5] He made his first field trip in September 1928 in Turkmenistan, and in 1930 visited the Altai Mountains. The museum supported another expedition to the Altais in 1932, and he returned in 1940, just before the war. In 1934 he made an expedition to Yakutia, which had great influence on the development of his ideas.[12]

During the 1930s and the Great Purge, Stalin sent many Soviet intellectuals to labor in the gulags. Yeleazar Meletinsky, often called Zorya, was among those imprisoned. He left his manuscript The Hero of the Fairy Tale with Tokarev, who preserved it for publication years later.[13] A crisis in Tokarev's career came on 20 August 1936 during the Trotsky-Zinoviev show trials, when meetings to denounce Trotsky and Zinoviev were arranged across the country. Tokarev publicly said that if the Trotskyite-Zinovievite faction had come to power they would have continued the communist party's political and economic policies, and argued in defense of his position. He was accused of taking a counter-revolutionary stance. On 21 August Tokarev was brought before the museum's Party Committee, and on 22 August a general staff meeting reviewed the speech. [14] Tokarev spoke in his own defense but was dismissed from the museum, although he suffered no other punishment.[15]

Later career

Tokarev retained his position at the State Academy of the History of Material Culture, where he had worked since 1932 as a Research Fellow in the Department of Feudalism. In October 1938 he rejoined the museum as an ethnographer and consultant. Until 1941, he was also a research associate at the Central Anti-religious museum. In 1939 Tokarev was appointed professor in the newly organized Department of Ethnography, History Department of Moscow State University, a position he held until 1973. From 1939 to 1941 he also lectured on ethnography at the Moscow Institute of History, Philosophy and Literature.[15] In 1940 Tokarev defended his doctoral dissertation "The social system of the Yakuts in the 17th-18th centuries."[1] In World War II, he was evacuated from Moscow in June 1941, and headed the history department of Abakan Teachers' Institute.[15] In 1943 he returned to Moscow and was awarded the title of professor, working as a section head of the Institute of Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.[1]

In 1951–1952, Tokarev was the first ethnographer from the Soviet Union to teach in the universities of Berlin and Leipzig.[16] He went to Berlin in 1951 as a guest of the Finno-Ugrian Institute. His visit may have been arranged by Wolfgang Steinitz, a Jewish specialist in Finno-Ugrian languages who had emigrated from Germany to the Soviet Union in 1933.[17] Tokarev lectured in the German Democratic Republic, stressing how important it was to study social and cultural changes that were occurring in both urban and rural areas. He said the goal of ethnology must be to describe and understand the "way of life" of the people being studied, and the changes that occurred to the way of life.[18]

From 1961 Tokarev headed up the institute's sector on the ethnography of non-Soviet nations in Europe. At the same time from 1956 to 1973 he was in charge of the Department of Ethnography within the History Department of Moscow State University. Under his leadership the department grew and expanded its scope of study. In particular, the study of Slavic, Siberian, Central Asian and African peoples, the history of these peoples and the history of primitive religions and of shamanism were points of attention. Tokarev died in Moscow on 19 April 1985.

Scientific activities

Ethnology

Tokarev was a follower of Aleksandr Nikolaevich Maksimov, who had undertaken early studies of Siberian and Australian hunter-gatherers. Maksimov believed that an ethnologist should not restrict himself to "primitive" people, but should study people at all stages of development.[19] Tokarev had extremely broad ethnographical interests, and was particularly intrigued by early forms of religion. He wrote about the peoples of Australia, Oceania, America and Europe, and about the Yakuts and the Altay people of Siberia. He wrote about how ethnology had evolved in Russia and in the west.[20] Tokarev conformed to Soviet Marxist ideology and Russian nationalist views in his study of the history of anthropology.[21] Joseph Stalin, who took power in the Soviet Union in 1924, imposed rigid constraints on the study of ethnography that were lifted only after his death in 1953. Tokarev's work continued to advocate a Marxist ethnography.[22]

According to a pupil, Tokarev said once that the Australian Aborigines were

...one of the most interesting peoples on the earth, and that Australian studies were one of the most fascinating and promising areas of ethnography. The study of the Australian Aborigines is the key factual base for any study of primitive society.[23]

In the 1920s, Tokarev was one of the first to try to create a conventional code for recording the meaning of kinship terms. He noted that it was misleading for a scholar to simply translate terms used by a people being studied into terms used by the scholar. He tried to define a system that used the numbers 1–6 to represent father, mother, son, daughter, husband and wife, and that reduced all other kinship terms to these basic terms.[24] He recorded new insights in his later work on ethnic groups of the USSR. For example, he noted that while in most Russian villages the witches were male, Ukrainian villages had many more female witches, which he thought might be due to western European influence via Poland.[25] He noted that the Slavonic people, from the steppes, worshipped stones, streams and hills, while the Finno-Ugrian people, from the forests, worshipped trees or groves.[26]

Tokarev's study, The Yakut social system in the 17th and 18th century (1945), inquired into the social and land ownership relations of the Sakha people of Yakutia from a Marxist historical perspective. He explored the question of whether the concept of private land ownership existed in Sakha society before the intervention of Russia.[27] He said:

The rapacious nature of the Tsarist conquerors in Siberia and in Yakutia has been acknowledged even by the bourgeois-exploitative camp of historians…Indications of...pogroms, murder and theft perpetrated against the iasak population on the part of service people begin with a 1638 order to the first Yakut general P. Golovin, and repeat in every subsequent order given to the generals.[28]

But after describing abuses of the colonizers, Tokarev noted that the Sakha prospered and grew in numbers in the longer term, and that other colonial regimes had been much more brutal.[28] This was in line with Soviet propaganda of World War II, when the Soviet government was trying to rally the peoples of the country to form a common front against the German invaders.[29] After the war, there was a resurgence of Russian nationalism in the mid-1950s. In Yakutia from the 1630s to 1917 (1957), published under his direction, the violence, murder, and enslavements are treated as isolated incidents in a generally peaceful movement of Russians into the territory. Leaders of the local people are often characterized as the instigators of the violence.[30]

Religion

Tokarev was interested in "primitive" religions. He tended to follow Lev Shternberg's evolutionist views, although rejecting some of Shternberg's specific hypotheses.[31] In 1963 he published a general discussion of the subject, Early forms of religion and its development, and religion in the history of nations. In this book, Tokarov concluded that Siberian shamanism had evolved from animism, since the shaman's role was to maintain a close relationship with the spirits of hunted animals.[32] Taking a Marxist view of the religious experience, in the 1980s Tokarev wrote that shamans "were almost always mentally ill, with a propensity for fits of madness." This was not a view that most of his colleagues shared by this time, preferring to describe tribal spirituality in terms of "primal religion".[33] Some of his other ideas about folklore and religion were considered alien, if not outdated, by western scholars. He associated sacred objects with fetishes, and sacred formulae with magic formulae.[34]

Tokarev depended on Orthodox missionary scholars for his knowledge of Islam.[35] His 1963 work takes a scientific atheist view of the subject, but betrays his reliance on missionaries as he relates Muslim terms to their Christian equivalents. For example, he describes the Mahdi as "the Messiah in Islam", and discusses "Muslim Clergy" and a "Muslim Church", all concepts that Russian scholars of Islam in the 19th century had understood to be inaccurate.[36] He observed that religion is more about how people relate to each other in relation to religious beliefs, than about the nature of these beliefs.[37] Tokarev's view that religions are more than a theology, and comprise a social force affecting many aspects of people's lives, was controversial among Soviet scholars of religion. He challenged the prevalent negative view at the time, which perceived Islam as a potential tool for the bourgeoisie and reactionaries, and not one that could be used to solve the problems of the masses. He showed that Islam could be used effectively by politicians with secular goals, and that Islamic socialism could be a positive force in the development of contemporary Muslim states.[38]

Later work

In 1959 Tokarev co-authored Narody Ameriki (The people of America) with A. V. Efimov. The introduction noted the book was the first generalized work on the history and ethnography of the peoples of America based on Marxian and Leninist methodology. An American reviewer wrote,

Predictably enough, the book is an unhappy union of semihonest description and Soviet dogma. Its anthropological value, if indeed it can be said to have any, is most apparent in its digest of several Russian and American sources on Aleut culture, The rest of the book is a pedestrian description of standard anthropological sources, periodically enlivened by accusations of capitalistic "exploitation", "enslavement", "oppression", and the like.[39]

Tokarev continued to write and edit prolifically throughout the remainder of his life. With the thaw in Soviet-Chinese relations in the late 1980s, his recent work began to be translated into Chinese.[40] He served as principal editor of the encyclopedia, Myths of the countries of the world. In the introduction he said, "Although myth conveys a story, it is not specifically a genre of literary art but only a certain worldview; often it is storytelling, but in other cases, the general mythic worldview expresses itself through rites, dances and songs."[41]

Teaching

Many of the students to whom Tokarev taught the theory and methodology of foreign ethnography during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s later became Siberianists.[42] Tokarev said that the ethnographic study should not be confined to the straightforward chronicling of material culture.[43] He stressed the human aspects, saying, "A material object cannot interest the ethnographer unless he considers its social existence, its relationship to man."[44] He considered that anthropology was "a historical science, studying peoples and their way of life and culture." He wrote, "Historicism is one of the basic principles of the Marxist method. Any subject, any phenomenon can only have its reality understood and known by approaching it from a historical point of view, by revealing its origin and development."[45]

Honors

Tokarev was awarded the Double Knight of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1945 and 1979) and Chevalier of the Order of Friendship of Peoples (1975). He was given the Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945" (1945), and the USSR State Prize in 1987, posthumously. He was named an Honored Scientist of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (1956) and Honored Scientist of Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1971).[1]

Scientific works

- Pre-capitalist survivals in Oirot. M. OGIZ-Sotsekgiz, 1936.

- Essay on the History of the Yakut people. M. Sotsekgiz, 1940.

- The social system of the Yakuts. Moscow, Yakutsk State. Press, 1945.

- The religious beliefs of the peoples of East 19th – early 20th centuries. Izd-vo AN SSSR, 1957.

- Ethnography of the USSR. Univ. Press, 1958. Translated into IT. language – Tokarev Sergej A. URSS: popoli e costume. Bari, Editori Laterza, 1969.

- Early forms of religion, and their development. Pergamon Press, 1964.

- History of Russian ethnography. Pergamon Press, 1966.

- The origins of ethnography. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1978.

- The history of foreign ethnography. MA, Graduate School, 1978.

- Religion in the history of the world. M., Politizdat, 1964. 2nd ed. M., Politizdat, 1965. 3rd ed. M., Politizdat, 1976. 4th ed. M., Politizdat, 1986. 5th ed. M., The Republic, 2005. Translated into different languages.

- Early forms of religion. Sat articles. M., Politizdat, 1990.

- Favorites. The theoretical and historiographical articles on the ethnography of the peoples and religions of the world. M., 1990.

- Tokarev Sergej A. Trieste 1946–47 nel diario di un componente sovietico della commissione per i confine italo-jugoslavi. Trieste, Del Bianco editore, 1995.

- Tokarev SA Religioni del mondo antico dai primitive ai celti. Milano, Teti, 1981.

- Answer. Editor: A History of the Yakut ASSR. Izd-vo AN SSSR, 1957. 2nd that.

- Answer. Editor and author of chapters: In a multi-volume series "The peoples of the world. Ethnographic Essays ": 1) The people of Australia and Oceania. Pergamon Press, 1956. 2) *The people of America. In 2 vols. Pergamon Press, 1959. 3) The peoples of Europe overseas. In 2 vols. Pergamon Press, 1964.

- Answer. Editor and author of chapters: Fundamentals of ethnography. Textbook. MA, Graduate School, 1968.

- Answer. Editor and author of chapters: Calendar customs and traditions of foreign countries in Europe. In 4 volumes. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1973, 1977, 1978, 1983.

- In the scientific and popular 20-volume edition of "Countries and Peoples": 1) Ed. Ed.: Overseas Europe: Western Europe. M., Thought, 1979. 2) Answer. Ed.: Overseas Europe: Eastern Europe. M., Thought, 1980. 3) A member of the main edition. College: Western Europe: Northern Europe. M., Thought, 1981.

- Answer. Editor: JG Frazer The Golden Bough . M., Politizdat, 1980. 2nd ed. M., Politizdat, 1983.

- Answer. Editor: JG Frazer Folklore in the Old Testament . M., Politizdat, 1985.

- Answer. Editor and writer: Myths of nations of the world . In 2 vols. M. Izdatelstvovo "Soviet Encyclopedia" . In 1980. 2nd ed. Moscow, Publishing House "Soviet Encyclopedia", 1987.

He published over 200 articles and introductions to different editions.

References

Notes

- Valerian Borisovich Aptekar (Russian: Валериа́н Бори́сович Апте́карь, 24 October 1899 – 29 July 1937) was later accused of anti-soviet activity, arrested and executed.[8]

Citations

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 121.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 122.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 123.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 125.

- Knight 2004, p. 470.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 124.

- Boškovi 2008, p. 28.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 127.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 128.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 129.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 126.

- Kabo 1998, p. 155.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 131.

- Anchabadze 2010, p. 132.

- Sárkány, Hann & Skalník 2005, p. 28.

- Sárkány, Hann & Skalník 2005, p. 28-29.

- Kockel, Craith & Frykman 2012, p. 113.

- Barnard 2004, p. 81.

- Kabo 1998, p. 189.

- Kan 2009, p. xvi.

- Guldin 1994, p. 119.

- Kabo 1998, p. 289.

- Dragadze 1984, p. 249.

- Clements, Engel & Worobec 1991, p. 151.

- Relve 1998, p. 106.

- Takakura 2006.

- Hicks 2005, p. 143.

- Hicks 2005, p. 144.

- Hicks 2005, p. 145.

- Kan 2009, p. 440.

- Hoppal 1997, p. 9.

- Znamenski 2004, p. 58.

- Bianchi 1975, p. 193.

- Kemper & Conermann 2011, p. 73.

- Kemper & Conermann 2011, p. 75-76.

- Kozintsev & Martin 2012, p. 125.

- Cole 1986, p. 282.

- Edgerton 1959, p. 902-903.

- Guldin 1994, p. 127.

- Adamenko 2007, p. 234.

- Gray, Vakhtin & Schweitzer 2003, p. 199.

- Belkov 2004, p. 29.

- Schoemaker 1992, p. 197.

- Jackson 1987, p. 156.

Sources

- Adamenko, Victoria (2007). Neo-Mythologism in Music: From Scriabin And Schoenberg to Schnittke And Crumb. Pendragon Press. ISBN 978-1-57647-125-8. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anchabadze, Yuri D. (2010). "С.А.ТОКАРЕВ: НАЧАЛО ПУТИ [S.A.TOKAREV initial way]" (PDF). ИСТОРИЯ НАУКИ (History of Science) (in Russian) (3). Retrieved 2012-09-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barnard, Alan (2004-10-15). Hunter-Gatherers in History, Archaeology and Anthropology. Berg. ISBN 978-1-85973-825-2. Retrieved 2012-08-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Belkov, Pavel (2004). "Cultural Anthropology: The State of the Field" (PDF). Антропологический Форум. Retrieved 2012-08-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bianchi, Ugo (1975). The History of Religions. Brill Archive. p. 193. ISBN 978-90-04-04237-7. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boškovi, Aleksandar (2008-03-16). Other People's Anthropologies: Ethnographic Practice on the Margins. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-398-5. Retrieved 2012-09-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clements, Barbara Evans; Engel, Barbara Alpern; Worobec, Christine D. (1991-07-17). Russia's Women: Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07024-0. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cole, Juan R. I. (1986-05-28). Shi'ism and Social Protest. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03553-7. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dragadze, Tamara (1984). Kinship and Marriage in the Soviet Union: Field Studies. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-0995-1. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edgerton, Robert B. (1959). "Narody Ameriki . A. V. Efimov, S. A. Tokarev". American Anthropologist. 61 (5): 902–903. doi:10.1525/aa.1959.61.5.02a00250.

|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Gray, Patty A.; Vakhtin, Nikolai; Schweitzer, Peter (2003). "Who owns Siberian ethnography? A critical assessment of a re-internationalized field" (PDF). Sibirica. 3 (2). doi:10.1080/1361736042000245312.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Tokarev, Sergei Aleksandrovich". Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (1970–1979). 6. The Gale Group, Inc.

- Guldin, Gregory Eliyu (1994). The Saga of Anthropology in China: From Malinowski to Moscow to Mao. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-56324-186-4. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hicks, Susan M. (2005). "BETWEEN INDIGENEITY AND NATIONALITY: THE POLITICS OF CULTURE AND NATURE IN RUSSIA'S DIAMOND PROVINCE" (PDF). University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 2012-08-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoppal, Mihaly (1997). "NATURE WORSHIP IN SIBERIAN SHAMANISM" (PDF). Folklore. 4. Retrieved 2012-08-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Anthony (1987). Anthropology at Home. Tavistock Publications. ISBN 978-0-422-60560-1. Retrieved 2012-08-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kabo, Vladimir Rafailovich (1998). The Road to Australia: Memoirs. Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-0-85575-312-2. Retrieved 2012-08-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kan, Sergei A. (2009-06-01). Lev Shternberg: Anthropologist, Russian Socialist, Jewish Activist. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1603-7. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kemper, Michael; Conermann, Stephan (2011-01-26). The Heritage of Soviet Oriental Studies. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-59977-1. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knight, Nathaniel (2004). "Ethnography, Russian and Soviet" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Russian History. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 978-0-02-865907-7. Retrieved 2012-08-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kockel, Ullrich; Craith, Mairead Nic; Frykman, Jonas (2012-03-22). A Companion to the Anthropology of Europe. John Wiley & Sons. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4443-6215-2. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- Kozintsev, Alexander; Martin, Richard (2012-03-31). The Mirror of Laughter. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-4764-3. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Relve, Hendrik (October 5–10, 1998). "THE FOREST ROOTS OF ESTONIANS". Proceedings of the 4th Biannual Conference of the Taiga Rescue Network. Retrieved 2012-08-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sárkány, Mihály; Hann, C. M.; Skalník, Peter (2005). Studying Peoples in the People's Democracies: Socialist Era Anthropology in East-Central Europe. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-8048-4. Retrieved 2012-08-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schoemaker, George H. (1992). "ACCULTURATION AND TRANSFORMATION OF SALT LAKE TEMPLE SYMBOLS IN MORMON TOMBSTONE ART". Markers IX – Journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies. ISBN 978-1-878381-02-6. Retrieved 2012-08-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Takakura, Hiroki (December 2006). "Indigenous Intellectuals and Suppressed Russian Anthropology". Current Anthropology. 47 (6): 1009–1016. doi:10.1086/508694. Retrieved 2012-08-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Znamenski, Andrei A. (2004). Shamanism: Critical Concepts in Sociology. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-33248-4. Retrieved 2012-08-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Alekseev VP Tokarev memory of Sergei Alexandrovich / / Sov. ethnography. In 1985. Number 4.

- Kozlov S. Ya ... and the day lasts longer than a century / / Ethnographic Review. Number 5. In 1999. pp. 3–15.

- Kozlov, S. J. imperturbable freedom / / NG Religion . September 12, 1999.

- SY Kozlov Sergey Tokarev (1899–1985) / / Portrait of historians. Time and fate. T. 4. Modern and Contemporary History. – Moscow: Nauka, 2004. S. 446–461.

- SY Kozlov Sergey Tokarev: "Ethnographic University" / / Outstanding domestic ethnologists and anthropologists of the 20th century. – Moscow: Nauka, 2004. S. 397–449.

- Markov, GE, TD Nightingale Ethnographic education at the Moscow State University (the 50th anniversary of the Department of Ethnography, History Faculty of Moscow State University) / / Sov. ethnography. 1990, No. 6.

- List of publications SA Tokarev (To his 80th birthday) / / Sov. ethnography. In 1980. Number 3.

- Scientific Council of the Institute of Ethnography, USSR Academy of Sciences dedicated to the memory of Sergei Alexandrovich Tokarev / / Sov. ethnography. In 1990. Number 4.

- Tokarev, S.A. (1983). "Religion and Religions From the Historical-Ethnographic Viewpoint". In Dube, S.C..; Basilov, V.N.. (eds.). Secularization in Multi-religious Societies: Indo-Soviet Perspectives. Concept Publishing Company. p. 125ff. GGKEY:ERERFKLZ3E7. Retrieved 2012-08-17.