Silenced (film)

Silenced (Korean: 도가니; RR: Dogani; MR: Togani; English: "The Crucible") is a 2011 South Korean drama film based on the novel The Crucible by Gong Ji-young,[2] starring Gong Yoo and Jung Yu-mi. It is based on events that took place at Gwangju Inhwa School for the hearing-impaired, where young deaf students were the victims of repeated sexual assaults by faculty members over a period of five years in the early 2000s.[3][4]

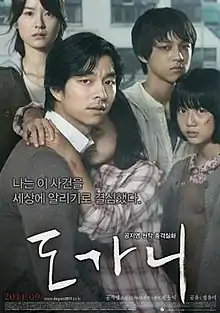

| Silenced | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Hangul | 도가니 |

| Revised Romanization | Dogani |

| McCune–Reischauer | Togani |

| Directed by | Hwang Dong-hyuk |

| Produced by | Uhm Yong-hun Bae Jeong-min Na Byung-joon |

| Written by | Hwang Dong-hyuk |

| Based on | The Crucible by Gong Ji-young |

| Starring | Gong Yoo Jung Yu-mi |

| Music by | Mowg |

| Cinematography | Kim Ji-yong |

| Edited by | Hahm Sung-won |

Production company | Samgeori Pictures |

| Distributed by | CJ Entertainment |

Release date |

|

Running time | 125 minutes |

| Country | South Korea |

| Language | Korean Korean Sign Language |

| Box office | US$30.7 million[1] |

Depicting both the crimes and the court proceedings that let the teachers off with minimal punishment, the film sparked public outrage upon its September 2011 release, which eventually resulted in a reopening of the investigations into the incidents. With over 4 million people in Korea having watched the film, the demand for legislative reform eventually reached its way to the National Assembly of South Korea, where a revised bill, dubbed the Dogani Bill, was passed in late October 2011 to abolish the statute of limitations for sex crimes against minors and the disabled.[5]

Plot

Kang In-ho is the newly appointed art teacher at Benevolence Academy, a school for hearing-impaired children in the fictional city of Mujin, North Jeolla Province. He has a dark past - his wife committed suicide a year ago, and his sick daughter is under the care of his mother. He is excited to teach his new students, yet the children are aloof and distant, trying to avoid running into him as much as possible. In-ho does not give up trying to show the kids that he cares. When the children finally open up, In-ho faces the shocking and ugly truth about the school and what the students have been enduring in secret: the children are being physically and sexually abused by their teachers. When he decides to fight for the children's rights and expose the crimes being committed at the school, In-ho teams up with human rights activist Seo Yoo-jin, but he and Yoo-jin soon realize the school's principal and teachers, and even the police, prosecutors and churches in the community are actually trying to cover up the truth.[6][7][8][9] In addition to using "privileges of former post", the accused do not hesitate to lie and bribe their way to get very light sentences. Using their last night of freedom to go out partying, the Lee brothers are last seen laughing that the judge was so easy to pay off for a light sentence. As Park (one of the offending teachers) leaves the party and walks home, he bumps into Min-su (one of the victims) along the way. Attempting to force the boy to come to his home to be raped once more, Park is shocked when Min-su stabs him in the side with a knife, having fallen into despair at his grandmother giving away his chance to put Park away for good. Park, brushing off the stabbing, smacks Min-su to the ground, where he begins viciously beating and kicking the boy, proclaiming that before he goes to prison, he's going to beat Min-su to death. As he prepares to finish Min-su off, Park is overpowered by the boy, who flings the both off them onto a nearby railroad track. As a coming train barrels toward them, Park begins screaming at Min-su, but, using Park's knife wound, keeps Park held down. Ultimately, the train runs over both the screaming Park and Min-su, the latter refusing to let the rapist get away with his acts, and they are both killed by the train. Later, Kang, Yeondoo and Yoori is seen mourning Minsu's death in a tent. A group of protesters and activists are seen demonstrating a protest and police trying to disperse them But since most are deaf - mute they proceed towards forced dispersal. The police force uses water cannons. As the clash is going on. Kang comes out with the picture of Minsu and stand amid it. He says "Everyone, This boy could neither hear nor speak. This child is called Minsu" repeatedly, before he was caught by the police. The movie ends with the words of Seo Yoo-jin's email updating Kang about the appeal and the children's condition.

Cast

- Gong Yoo - Kang In-ho

- Jung Yu-mi - Seo Yoo-jin

- Kim Hyun-soo - Kim Yeon-doo

- Jung In-seo - Jin Yoo-ri

- Baek Seung-hwan - Jeon Min-su

- Kim Ji-young - In-ho's mother

- Jang Gwang - headmaster twin brothers Lee Kang-suk and Lee Kang-bok

- Im Hyeon-seong - Young-hoon

- Kim Joo-ryung - Yoon Ja-ae

- Kim Min-sang - Park Bo-hyun

- Um Hyo-sup - police officer Jang

- Jeon Kuk-hwan - Attorney Hwang

- Choi Jin-ho - prosecutor

- Kwon Yoo-jin - judge

- Park Hye-jin - headmaster's wife

- Kim Ji-young - Kim Sol-yi (In-ho's daughter)

- Eom Ji-seong - Young-soo

- Lee Sang-hee - auto repair shop owner

- Nam Myung-ryul - Professor Kim Jung-woo

- Jang So-yeon - courtroom sign language interpreter

- Hong Suk-youn - school custodian/guard

Impact

The film sparked public outcry over lenient court rulings, prompting police to reopen the case and lawmakers to introduce bills for the human rights of the vulnerable.[10] Four out of the six teachers at the Gwangju Inhwa School for whom serious punishment was recommended by the education authority were reinstated after they escaped punishment under the statute of limitations.[11] Only two of them were convicted of repeated rapes of eight young students and received jail terms of less than a year.[12] 71-year-old ex teacher Kim Yeong-il recently claimed that two children had died when the incident took place in 1964, after which he was beaten and forced to resign his job by the vice principal.[13][14] Two months after the film's release and resulting controversy, Gwangju City officially shut down the school in November 2011.[15] In July 2012, the Gwangju District Court sentenced the 63-year-old former administrator of Gwangju Inhwa School to 12 years in prison for sexually assaulting an 18-year-old student in April 2005. He was also charged with physically abusing another 17-year-old student who had witnessed the crime (the victim reportedly attempted to kill themselves afterward). The administrator, only identified by his surname Kim, was also ordered to wear an electronic anklet for 10 years following his release.[16][17]

In 2011, the Korean National Assembly passed the "Dogani Law" (named after the Korean name of the film), removing any statute of limitations for sexual assault against children under 13 and the disabled. It also raised the minimum sentence for rape of young children and the disabled to up to life in prison, and abolished a clause requiring that victims prove they were "unable to resist" due to their disability.[18]

Reception

For the past few years, we have seen almost no South Korean films that actively examined the state of our society, the values of what is right, and what we need to do the way The Crucible does.

— Film critic Ahn Si-hwan[19]

In Korea the film ranked #1 for three consecutive weeks and grossed ₩7.8 billion in its first week of release[19][20] and grossed a total of ₩35 billion after ten weeks of screening.[21][22]

After the film's release, the bestselling book of the same name by author Gong Ji-young, which first recounted the crimes and provided the bulk of the film's content, topped national bestseller lists for the first time in two years.[5] Ruling conservative political party Grand National Party (GNP) then called for an investigation into Gong Ji-young for engaging in "political activities", a move that was met with public derision.[23]

It received the Audience Award at the 2012 Udine Far East Film Festival in Italy.[24]

Conversations about the film and its impact re-emerged when the Samsung Economic Research Institute (SERI) released its annual survey of the year's top ten consumer favorites on December 7, 2011. Based on a poll of market analysts and nearly 8,000 consumers, SERI's "Korea’s Top Ten Hits of 2011" ranked Silenced among the year's top events.[5]

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 32nd Blue Dragon Film Awards | Best Film | Silenced | Nominated |

| Best Director | Hwang Dong-hyuk | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor | Gong Yoo | Nominated | ||

| Best Actress | Jung Yu-mi | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Jang Gwang | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay | Hwang Dong-hyuk | Nominated | ||

| Best Music | Mowg | Won | ||

| Popular Star Award | Gong Yoo | Won | ||

| 2012 | 48th Baeksang Arts Awards | Best Actor | Nominated | |

| 49th Grand Bell Awards | Best Film | Silenced | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Kim Hyun-soo | Nominated | ||

| KOFRA Film Awards | Best Film | Silenced | Won | |

| Udine Far East Film Festival | Audience Award | Hwang Dong-hyuk | Won | |

| Black Dragon Audience Award | Won |

International release

The film's international title is Silenced. On November 4, 2011, the film was released in select theaters in Los Angeles, San Jose, Huntington Beach, New Jersey, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Dallas, Chicago, Seattle, Portland, Las Vegas, Toronto and Vancouver. It has been reviewed by The Wall Street Journal,[25] The Economist[26] and The New York Times.[27]

See also

- Cinema of Korea

- List of South Korean films

- Gwangju Inhwa School

References

- Dogani (Crucible) Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2012-04-25

- Fueled by need for fresh material, best-sellers become box office hits Archived 2013-01-27 at Archive.today JoongAng Daily. 9 September 2011. Retrieved 2012-04-25

- "'The Crucible' Brings Demons of Child Molestation Case Back to Life" Chosun Ilbo. 28 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-15

- Film examines child abuse case Korea Times. 24 August 2011. Retrieved 2012-04-25

- Kwon, Jungyun (15 December 2011). "A look back at the year's breakout films". Korea.net. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- Real life case of child abuse explored in The Crucible The Hankyoreh. 9 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-15

- The Crucible (2011) The Chosun Ilbo. 23 September 2011. Retrieved 2012-04-25

- 2011.9.23 NOW PLAYING Archived 2012-07-10 at Archive.today JoongAng Daily. 23 September 2011. Retrieved 2012-04-25

- Now showing Korea Times. 22 September 2011. Retrieved 2012-04-25

- "Sexual abuse of disabled, vulnerable, or Dead people on the rise" Yonhap News. 29 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-15

- "Deaf School Teachers Face Firing Over Sex Abuse Scandal" Chosun Ilbo. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-15

- "Box-office hit sheds new light on sex crimes against disabled students" Yonhap News. 30 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-15

- "광주 인화학교 50년전 학생 암매장 폭로(종합)" Yonhap News. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-08 (in Korean)

- "경찰, 47년 전 인화학교 학생 암매장 의혹 조사" Yonhap News. 18 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-08(in Korean)

- "'Dogani' school to be shut down" Korea Times. 31 October 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-31

- "Gwangju school sex offender gets 12 years in prison". Korea Times. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- "Gwangju school sex offender gets 12 yrs in prison". Yonhap News. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- "National Assembly passes 'Dogani Law'". koreatimes. 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- "'The Crucible' surpasses 1 million viewers at box office" The Hankyoreh. 28 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-15

- "South Korea Box Office: September 23–25, 2011" Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2012-04-19

- "South Korea Box Office: November 25–27, 2011" Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2012-04-19

- Victims at Deaf School Meet Film Stars During Seoul Tour Chosun Ilbo. 6 January 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-25

- "GNP calls for investigation into 'The Crucible' author" The Hankyoreh. 29 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-08

- 2 films won Audience Award at Far East Film Festival Korea Times. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-30

- Woo, Jaeyeon "Unsettling ‘Dogani’ Revisits School Horror" The Wall Street Journal. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-08

- "Silent for too long" The Economist. 11 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-08

- Choe, Sang-Hun "Film Underscores Koreans' Growing Anger Over Sex Crimes" The New York Times. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-08

External links

- Official website (in Korean)

- Official website (in English)

- Silenced at IMDb

- Silenced at HanCinema