Slavery in New Spain

Slavery in New Spain was based mainly on the importation of slaves from Africa to work in the colony in the enormous plantations, ranches or mining areas of the viceroyalty, since their physical consistency made them suitable for working in warm areas.[1]

In 1517 Charles V established a system of concessions by which his subjects in America could use slaves, thus starting the slave trade. When the Spanish settled in New Spain, they brought some workers with them as slaves. For their part, the Dominican friars who arrived in America denounced the slave condition in which the natives lived. Moreover, like bishops of other orders, they opposed the unjust and illegal treatment before the audience of the Spanish king and in the Royal Commission afterwards.[2]

A bull promulgated by Pope Urban VIII on 22 April 1639 prohibited slavery in the colonies of Spain and Portugal in America. The measure was approved by the King of Spain Philip IV of Spain on the indigenous people, but allowed the enslavement of African slaves. Many of these slaves, known as Cimarrones, obtained their freedom by escaping and taking refuge in the mountains of Orizaba, Xalapa and Córdoba in the state of Veracruz.

African slavery

In addition to the Indians and the Spaniards, Africans constitute the third root of the mestizo society in Mexico, which has its origin in New Spain. The international commercial exchanges of that period were not only reduced to products, but also included the humans themselves. Africa became the continent that supplied slaves to the world. Thus, the African population arrived in New Spain as slaves to be employed in the heaviest jobs. Given the reduction of the indigenous population caused by demographic disasters, the extraction of people from Africa as slaves also contributed to one of the disasters registered in modern history if we consider that of the millions of people who left Africa as slaves, many of them would die on the way because of the inhuman conditions in which they were transferred and those who managed to survive were forced to do heavy work in agriculture and livestock farming under the same conditions.

Slaves from Africa were seen as a way to meet the demand for labour. In 1521 the Africans in New Spain were no more than a dozen and by 1570 there were about 20,000; in 1646 they numbered more than 35,000, although the population declined and by 1810 they were about 10,000, distributed mainly along the coasts and in tropical areas. They were destined for crops such as sugar cane. Slavery continued to be a phenomenon whose activities yielded large profits.

This practice affected both men (for activities that required a lot of physical strength) and women (for domestic service activities, where they played the roles of wet nurses, washerwomen, cooks, or were responsible for the personal care of their masters). [3]

The Holy Office clearly enjoyed a reputation among slaves as a possible way out of the harsh conditions in which they lived. In the absence of effective civil courts where a complaint of mistreatment could be filed, Afro-Mexicans saw the Inquisition as a way to alleviate this miserable situation.[4]

There were two main methods of offering judicial protection to slaves in New Spain:

- The first was preventive, consisting of unannounced and sporadic visits to a worksite to record abuses against the labor force, of which slaves formed a significant part.

- The second method was punitive in nature, and occurred when witnesses or the slaves themselves denounced their owner for mistreatment before the Holy Office or audience. However, cases of protection were very rare throughout the colonial period.[5]

Indigenous slavery

The conquest gave rise to the first cases of slavery in New Spain, due to the law of the Spanish. Before the army of Hernán Cortés went into Colhuacan, the soldiers asked the crown from Veracruz to allow them to send slaves from Spain for the service and sustenance of their troops. They foresaw that since this was the land that they were going to conquer for a long time and with many people, some caciques would not want to come to the knowledge of the Catholic faith nor to the king's servitude and would wage war, in which case they asked that, subjugated by force, they could give and distribute slaves "as is customary in the land of infidels, for it is a very just thing"'.[6]

Spanish settlers acquired indigenous slaves in New Spain, just as they did in the West Indies. They acquired them mainly in two ways: the captivity of those who had been defeated in war, and the rescue of those reduced to servitude by the Indians themselves. In the first case, slavery was imposed on people who might have been free before the arrival of the Spaniards. In the second case, the ancient servitude was prolonged, replacing its features with those of European law. Slaves could be traded under the Spanish regime and to safeguard the master's property, they were shod in the face or body. Legally and in practice, their condition was more disadvantageous than that of the free Indians.

On 14 May of 1524, the royal iron arrived in New Spain, sent by the King of Spain to mark (on the leg, buttock, arm or face) the Indian slaves, known as "ransom iron". Subsequently, the position prohibiting the enslavement of indigenous people by purchase or inheritance was successfully enforced, although it was permitted only in the case of war captives. This category included, above all, the indigenous peoples of the north of the country who resisted Spanish rule; this was reflected in the so-called New Laws of 1542 which punished this practice. The Indians were considered to be physically weaker than the Africans, and so attempts were made to protect them.These laws strictly forbade the practice of slavery in the future and mandated a review of existing cases of servitude. Slavery of Indians for war and ransom was prohibited. However, freedom was granted to those in servitude, and the possibility arose that Spanish law would agree by exception to the captivity of Indians who remained in a hostile attitude.[7]

Despite the laws, the exploitation did not disappear, and this, together with the infectious diseases, ended up considerably reducing the population, which was immunologically fragile to the microorganisms carried by both Europeans and Africans. The decline of the indigenous population was serious and to avoid stopping production on Virrey Enríquez in 1580, he advised the purchase of black slaves on behalf of the king, to distribute them at cost to miners, owners of sugar cane fields and mills and other Spanish businessmen. From then on, the legal introduction of African slaves increased; five thousand a year were authorized for New Spain.[8]

Abolition

People who found themselves as "slaves" could buy their freedom by obtaining a loan or by being released from their masters before they died. There were also cases of slaves escaping from their masters, and to avoid being recaptured they sought refuge in areas that were difficult for their persecutors to reach, such as jungles and mountains. As the number of escaped slaves increased, small populations emerged that would be known as Palenques. Freed slaves who feared being subjugated again began to arrive at such sites.

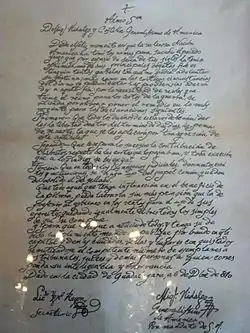

The abolition of slavery was part of the ideology of the insurgents during the war of Mexican independence, so that on the instructions of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla this provision was published by José María Anzorena on October 19, 1810 in Morelia, by Ignacio López Rayón in Tlalpujahua on October 24, 1810, by José María Morelos through the Bando del Aguacatillo on November 17, 1810,[9] and by Miguel Hidalgo himself through a side published in Guadalajara on 29 November 1810,[10] who also published and ordered to print the Decreto contra la esclavitud, las gabelas y el papel sellado on December 6, 1810 in the same square.[11] When Hidalgo died, the abolition of slavery was ratified by López Rayón in the Constitutional Elements in April 1812 and by José María Morelos in the Sentiments of the Nation in September 1813. Once Mexico's independence was consummated, the former insurgents Guadalupe Victoria and Vicente Guerrero ratified the abolition of slavery through presidential decrees, respectively during their terms of office, on September 16, 1825 and September 15, 1829.

See also

References

- Treviño, Héctor (1997). History of Mexico. Mexico: Castillo.

- [http://www.primariatic.sep.gob.mx/descargas/colecciones/proyectos/SEPIENSA_conectate_y_aprende/contenidos/h_mexicanas/colonia/poblacion_africana/africanos_2.html/ "The African population in New Spain" - Encyclopedia of the SEP Mexico }}

- "African women and descendants in Mexico City in the 17th century" pp. 215-216, in Rina Cáceres (compiler). Rutas de la esclavitud en América Latina", Costa Rica, Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica, 2001

- Slaves of the White God, 90-2; and Davidson, Negro Slave, 240- 41

- Slaves of the White God, 90-2; and Davidson, Negro Slave, 243

- Zavala, S. (1981). Indian slaves in New Spain. The National College. Mexico. p. 11.

- Zavala, Silvio Indian Slaves in New Spain. Edition of the National College. Mexico, 1981. p. 181.

- Historia General de México, Mexico, El Colegio de México, 2000, p. 319.

- Torre Villar, 2000; 406

- "Mr. Hidalgo's side abolishing slavery; repealing the laws regarding taxes; imposing alcabala for national and foreign effects; prohibiting the use of sealed paper, and extinguishing the tobacco, gunpowder, colors and other tobacco shops". 500 años de México en documentos. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- Villoro, Luis (2006). "The revolution of independence". Historia general del México, work prepared by the Centro de Estudios Históricos (1st edition). Mexico: El Colegio de Mexico. pp. 506.

Bibliography

- Carbajal Huerta, Elizabeth "History 2" Third grade. Larousse.

- Esquivel, Gloria (1996). History of Mexico. Oxford: Harla.

- Moreno, Salvador (1995). History of Mexico. Mexico: Ediciones Pedagógicas.

- Villar, Ernesto de la Torre (2000). Temas de la insurgencia (in Spanish). UNAM. ISBN 978-968-36-7804-1.

- Zavala, Silvio (1981). Indian Slaves in New Spain. Edition of the National College. Mexico

- "Africans and descendants in Mexico City in the 17th century" in Rina Cáceres (compiler). Rutas de la esclavitud en América Latina, Costa Rica, Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica, 2001