Small clause

In linguistics, a small clause consists of a subject and its predicate, but lacks an overt expression of tense.[1] Small clauses have the semantic subject-predicate characteristics of a clause, and have some, but not all, the properties of a constituent. Structural analyses of small clauses vary according to whether a flat or layered analysis is pursued. The small clause is related to the phenomena of raising-to-object, exceptional case-marking, accusativus cum infinitivo, and object control.

History

Williams (1975, 1980)

The term "small clause" was coined by Edwin Williams in 1975, who specifically looked at "reduced relatives, adverbial modifier phrases, and gerundive phrases".[2] The following three examples are treated in Williams' 1975 paper as"small clauses", as cited in Balazs 2012.[2] However, not all linguists do consider these to be small clauses according to the term's modern definition.

- The man [driving the bus] is Norton's best friend.

- John decided to leave, [thinking the party was over].

- [John's evading his taxes] infuriates me.[2]

The modern definition of a small clause is an [NP XP] in a predicative relationship. This definition was proposed by Edwin Williams in 1980, who introduced the concept of Predication.[3] He proposes that the NP and XP's relationship is based on co-indexation, which is made possible by c-command.[3] Williams believes that the [NP XP] small clause does not form a constituent.[4]

Stowell (1981)

Timothy Stowell in 1981 proposed that the small clause is indeed a constituent,[5] and proposed a structure for small clauses using X-bar theory.[5] Stowell proposes that the subject is defined as an NP occurring in a specifier position, that case is assigned in the specifier position, and that not all categories have subjects.[6] His analysis explains why case-marked subjects cannot occur in infinitival clauses, although NPs can be projected up to an infinitival clause's specifier position.[6] Stowell considers the following examples to be small clauses and constituents.

- I consider [John very stupid]

- I expect [that sailor off my ship]

- We feared [John killed by the enemy]

- I saw [John come to the kitchen][7]

These two syntacticians have proposed the two main analyses of small clauses. Williams' analysis follows the Theory of Predication, where the key difference is that the "subject" in this theory is the "external argument of a maximal projection".[4] In contrast, Stowell's theory follows the Theory of Small clauses, supported by linguists such as Chomsky, Aarts, and Kitagawa.[8] This theory uses X-bar theory to treat small clauses as constituents. Linguists debate which analysis to pursue, as there is evidence for both sides of the debate.

Small clause behaviour

A small clause divides into two constituents: the subject and its predicate. While small clauses occur cross-linguistically, different languages have different restrictions on what can and cannot be a well-formed (i.e., grammatical) small clause.[9] Criteria for identifying a small clause include:

- absence of tense-marking on the predicate

- possibility of negating the small clause predicate

- selectional restrictions imposed by the matrix verb that introduces the small clause

- constituency tests (coordination of small clauses, small clause in subject position, movement of small clause)

Absence of tense-marking

A small clause is characterised as having two constituents NP and XP that enter into a predicative relation, but lacking finite tense and/or a verb. Possible predicates in small clauses typically include adjective phrases (AP), prepositional phrases (PPs), noun phrases (NPs), or determiner phrases (DPs) (see determiner phrase page on debate regarding the existence of DPs).

There are two schools of thought regarding NP VP constructions. Some linguists believe that a small clause characteristically lacks a verb, while others believe that a small clause may have a verb but lacks inflected tense. The following three examples involve NP AP, NP DP, and NP PP constructions. These small clauses all lack verbs:

- I consider [Mary smart]

- I consider [Mary my best friend]

- I consider [Mary out of her mind]

In contrast, some linguists consider these following main clause examples to be minimally paired with the previous small clause examples with the critical difference being the inclusion of a verb preceded by an infinitival 'to':[1]

- I consider Mary to be smart

- I consider Mary to be my best friend

- I consider Mary to be out of her mind

Here, the presence of a verb and tense (the infinitival 'to') makes the bolded portions parts of the main clause rather than independent small clauses. In contrast, theorists who believe a small clause can have a verb and uninflected tense would judge these examples to be small clauses rather than main clauses.

The second theory proposes that small clauses lack inflected tense but can have a bare infinitival verb. Under this theory, NP VP constructions are allowed. The following examples contrast small clauses with non-finite verbs with main clauses with finite verbs.

- They think they are ready to leave.

- *They think they are ready left.

- They think they must leave.

The asterisk here represents that the sentence (2) is generally held to be ungrammatical by native English speakers.

Selected by Matrix Verb

Small clauses satisfy selectional requirements of the verb in the main clause in order to be grammatical.[10]

The argument structure of verbs is satisfied with small clause constructions. The following two examples show how the argument structure of the verb "consider" affects what predicate can be in the small clause.[11]

- I consider Mr. Nyman a genius.

- *I consider Mr. Nyman in my shed.

Example 2 is ungrammatical as the verb "consider" does take an NP complement, but not a PP complement.[11]

However, this theory of selectional requirement is also disputed, as substitution of different small clauses can create grammatical readings.

- I consider the team in no fit state to play.

- *I consider my friends on the roof.[12]

Both examples (a) and (b) take PP complements, yet (a) is grammatical while (b) is not.

The matrix verb's selection of case also supports the theory that the matrix verb's selectional requirements affect small clause licensing.

The verb "consider" marks accusative case on the small clause's subject NP.[11] This conclusion is supported by pronoun-substitution.

- I consider Natasha a visionary.

- I consider her a visionary.

- *I consider she a visionary.

In Serbo-Croatian, the verb "smatrati" (to consider) selects for accusative case for its subject argument and instrumental case as its complement argument.[13]

| I consider him a fool. | ||||

| (Ja) | smatram | ga | budalom/ | *budala. |

| I-NOM | consider | him-ACC | a fool-INSTR | *a fool-ACC. |

Semantically Determined

Small clauses' grammaticality judgments are affected by their semantic value.

The following examples show how semantic selection also affects predication of a small clause.[10]

- *The doctor considers that patient dead tomorrow.

- Our pilot considers that island off our route.

Some small clauses that appear to be ungrammatical can be well-formed given the appropriate context. This suggests that the semantic relation of the main verb and the small clause affects sentences' grammaticality.[11]

- *I consider John off my ship.

- As soon as he sets foot on the gangplank, I'll consider John off my ship.[14]

Negation

Small clauses may not be negated by a negative modal or auxiliary verb, such as don't, shan't, or can't.[15] Small clauses may only be negated by negative particles, such as not.[15]

- I consider Rome not a good choice.[15]

- *I consider Rome might not a good choice.

Constituency tests

There are a number of considerations that support or refute the one or the other analysis. The layered analysis, which, again, views the small clause as a constituent, is supported by the basic insight that the small clause functions as a single semantic unit, i.e. as a clause consisting of a subject and a predicate.

Coordination

Coordination assumes only constituents of a like type can be joined with a conjunction. Small clauses can be coordinated with conjunctions, which suggests they are constituents of a like type (see Coordination (linguistics) on controversy regarding effectiveness/accuracy of coordination constituency tests).

The example below shows small clause coordination for NP AP phrases, and NP NP/DP phrases respectively.

- He considers [Maria wise] and [Jane talented].

- She considers [John a tyrant] and [Martin a clown].

Subject of a small clause

The layered analysis is also supported by the fact that in certain cases, a small clause can function as the subject of the greater clause, e.g.

- Bill behind the wheel is a scary thought. - Small clause functioning as subject

- Sam drunk is something everyone wants to avoid. - Small clause functioning as subject

Concerning small clauses in subject position, see Culicover,[16]:p48 Haegeman and Guéron.[17]:p109

Complement of 'with'

Most theories of syntax judge subjects to be single constituents, hence the small clauses Bill behind the wheel and Sam drunk here should each be construed as one constituent. Further, small clauses can appear as the complement of with, e.g.:[17]

- With Bill behind the wheel, we're in trouble. - Small clause as complement of with

- With Sam drunk, we've got a big problem. - Small clause as complement of with

These data are also easier to accommodate if the small clause is a constituent.

Movement

One can argue, however, that small clauses in subject position and as the complement of with are fundamentally different from small clauses in object position. The data further above have the small clause following the matrix verb, whereby the subject of the small clause is also the object of the matrix clause. In such cases, the matrix verb appears to be subcategorizing for its object noun (phrase), which then functions as the subject of the small clause. In this regard, there are a number of observations suggesting that the object/subject noun phrase is a direct dependent of the matrix verb, which means the flat structure is correct: the small clause generally does not behave as a single constituent with respect to constituency tests; the object becomes the subject of the corresponding passive sentence; and when the object is a reflexive pronoun, it is coindexed with the matrix subject:

- a. She proved him guilty.

- b. *Him guilty she proved. - Small clause fails the topicalization diagnostic for identifying constituents.

- c. *It is him guilty that she proved. - Small clause fails the clefting diagnostic for identifying constituents.

- d. *What she proved was him guilty. - Small clause fails the pseudoclefting diagnostic for identifying constituents.

- e. *What did she prove? - ??Him guilty. - Small clause fails the answer fragment diagnostic for identifying constituents

- f. He was proved guilty. - Subject of small clause becomes the subject of matrix clause in the corresponding passive sentence.

- g. She1 proved herself1 guilty. - Reflexive pronoun takes the matrix subject as its antecedent.

These data are consistent with the flat analysis of small clauses. The object of the matrix clause plays a dual role insofar as it is also the subject of the embedded predicate.

Counter-Arguments

Small clauses' constituency status is not agreed upon by linguists. Some linguists argue that small clauses do not form a constituent, but rather forms a noun phrase.

One argument is that NP AP small clauses cannot occur in the subject position without modification.[18] However, these NP AP small clauses can occur after the verb without modification, such as in example 1.

- *[Lots of books dirty] is a common problem in libraries.

- [Lots of books dirty from mistreatment] is a common problem in libraries.

A second argument is coordination tests make incorrect predictions about constituency, particularly regarding small clauses. This casts doubt upon small clauses' constituency status.

- Louis gave [a book to Marie yesterday] and [a painting to Barbara the day before].[19]

Another counterexample of constituency looks at depictive secondary predicates.[20]

- They sponged the water up.

One school of thought argues that this example has [the water up] behaving as a constituent small clause, while another school of thought argues that the verb "sponge" does not select for a small clause, and that "the water up" semantically, but not syntactically, shows the resultative state of the verb.[20]

Structural analyses

Broadly speaking, there are three competing analyses of the structure of small clauses, flat, layered, and X-bar theory.[21] The flat analysis judges the subject and predicate of the small clause to be sister constituents, whereas the layered analysis and X-bar theory take them to form a single constituent.[22]

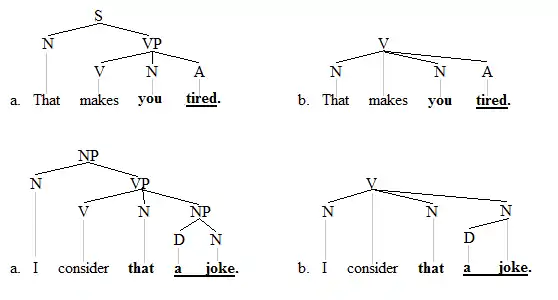

Flat structure

The flat structure organizes small clause material into two distinct sister constituents.[16]

The a-trees on the left are the phrase structure trees, and the b-trees on the right are the dependency trees. The key aspect of these structures is that the small clause material consists of two separate sister constituents.

The flat analysis is preferred by those working in dependency grammars and representational phrase structure grammars (e.g. Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar and Head-Driven Phrase structure Grammar).

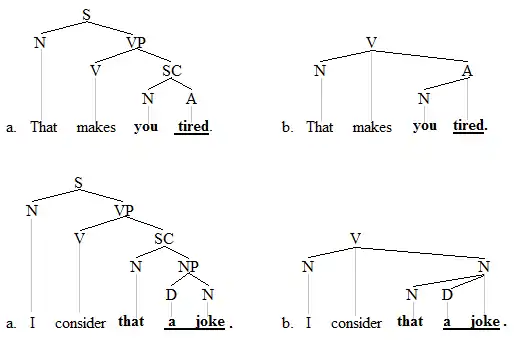

Layered structure

The layered structure organizes small clause material into one constituent. The phrase structure trees are again on the left, and the dependency trees on the right. To mark the small clause in the phrase structure trees, the node label SC is used.

The layered analysis is preferred by those working in the Government and Binding framework and its tradition, for examples see Chomsky,[23] Ouhalla,[24] Culicover,[16]:p47 Haegeman and Guéron.[17]:p108

X-Bar Theory structure

See X-Bar Theory for a general exploration of X-Bar Theory.

X-bar theory predicts that a head (X) will project into an intermediate constituent (X') and a maximal projection (XP). There were three common analyses of the internal structure of a small clause under X-Bar theory.[25] Here they are each presented as showing the NP AP small clause complement in the sentence (highlighted in bold), "I consider (NP)Mary (AP)smart":

The small clause as a symmetric constituent

.png.webp)

In this analysis, neither of the constituents determine the category, meaning that it is an exocentric construction. Some linguists believe that the label of this structure can be symmetrically determined by the constituents,[27][28] and others believe that this structure lacks a label altogether.[29] In order to indicate a predicative relationship between the subject (in this case, the NP Mary), and the predicate (AP smart), some have suggested a system of co-indexation, where the subject must c-command any predicate associated with it.[30]

This analysis is not compatible with X-bar theory because X-bar theory does not allow for headless constituents, additionally this structure may not be an accurate representation of a small clause because it lacks an intermediate functional element that connects the subject with the predicate. Evidence of this element can be seen as an overt realization in a variety of languages such as Welsh,[31] Norwegian,[32] and English, as in the examples below[31] (with the overt predicative functional category highlighted in bold):

- I regard Fred as insane.

- I consider Fred as my best friend.

Some have taken this as evidence that this structure does not adequately portray the structure of a small clause, and that a better structure must include some intermediate projection that combines the subject and the predicate[1] which would assign a head to the constituent.

The small clause as a projection of the predicate

.png.webp)

In this analysis, the small clause can be identified as a projection of the predicate (in this example, the predicate would be the 'smart' in 'Mary smart'). In this view, the specifier of the structure (in this case, the NP 'Mary') is the subject of the head[33] (in this case, the A 'smart'). This analysis builds on Chomsky's[34] model of phrase structure and is proposed by Stowell[35] and Contreras.[36]

The small clause as a projection of the functional category

.png.webp)

The PrP[37] (predicate phrase) category (also analyzed as AgrP,[38] PredP,[39] and P[40]), was proposed for a few reasons, some of which are outlined below:

- This structure helps to account for coordination where the categories of the items being coordinated must be the same. This accounts for the mystery of phrases such as example 1 below, where in the bolded small clause an adjective phrase (AP) is being coordinated with a noun phrase (NP), and it still has a grammatical reading. The addition of the PrP category helps to solve this issue by positing that the items being coordinated are under the intermediate projection of the Pr head, the Pr', as seen in example 2.[40]

- Mayor Shinn considered Eulalie (AP)talented and (NP)a tyrant.

- Mayor Shinn considered (PrP)Eulalie (Pr')(P) (AP)talented and (Pr')(P) (NP)a tyrant.

- This structure answers the question of the category of the word 'as' in small clause constructions such as "I regard Fred as my best friend". This structure was an issue because 'as' could only be analyzed as a prepositional phrase, but prepositions do not take adjective phrase complements. Analyzing 'as' as an overt realization of the Pr head, then the small clause structure under X-bar theory can be upheld.[37]

Additionally, some have theorized that a combination of the three structures can illustrate why the subjects of verbal small clauses and adjectival small clauses seem to behave differently, as noted by Basilico:[41]

- The prisoner seems/appears to be intelligent.

- The prisoner seems/appears intelligent.

- The prisoner seems/appears to leave every day at noon.

- *The prisoner seems/appears leave every day at noon.

Here, examples 1 and 2 show that adjectival small clauses are allowed to be raised to the matrix subject position (example 1 is in situ, and example 2 has been raised) but the same cannot be done to a verbal small clause in examples 3 and 4, where the * marks ungrammaticality. From this evidence, some linguists have theorized that the subjects of adjectival and verbal small clauses must differ in syntactic position. This conclusion is bolstered by the knowledge that verbal and adjectival small clauses differ in their predication forms. Adjectival small clauses involve categorical predication where the predicate ascribe a property of the subject, and verbal small clauses involve thetic predications, where an event that the subject is participating in is reported.[29] Basilico uses this to argue that a small clause should be analyzed as a Topic Phrase, which is projected from the predicate head (the Topic), where the subject is the specifier.[42] In this way, he argues that in an adjectival small clause, the predicate is formed for an individual topic, and in a verbal small clause the events form a predicate of events for a stage topic, which accounts for why verbal small clauses cannot be raised to the matrix subject position.[43]

Examples

Germanic: English

The following sentences contain (what some theories of syntax judge to be) small clauses.[44] The actual small clause is in bold in each example. In each of these sentences, the underlined expression functions as a predicate over the nominal immediately to its left.

- a. Susan considers Sam a dope.

- b. We want you sober.

- c. Jim called me a liar.

- d. They named him Pedro.

- e. Fred wiped the table clean.

- f. Larry pounded the nail flat.

The verbs that license small clauses like these are a heterogeneous set, and include

- raising-to-object or ECM verbs like consider and want

- verbs like call and name, which subcategorize for an object NP and a predicative expression

- verbs like wipe and pound, which allow the appearance of a resultative predicate.

What does and does not qualify as a small clause varies in the literature. Early discussions of small clauses were limited to the ECM-verbs like consider.

An important trait that all six examples above have in common is that the small clause lacks a verb. Indeed, this has been taken as a defining aspect of small clauses, i.e. to qualify as a small clause, a verb must be absent.[45][24][46] If, however, one allows a small clause to contain a verb, then the following sentences can also be interpreted as containing small clauses:[17]

- g. We saw Fred leave.

- h. Did you hear them arrive?

- i. Larry believes that to be folly.

- j. Do you judge it to be possible?

The similarity across the sentences a-f and these four sentences g-j is obvious, since the same subject-predicate relationship is present in all ten sentences. Hence if one interprets sentences a-f as containing small clauses, one can also judge sentences g-j as containing small clauses. A defining characteristic of all ten of the small clauses in a-j is that the tense associated with finite clauses, which contain a finite verb, is absent.

French

French small clauses may appear in an NP AP, NP PP, and NP VP constructions. However, there are some restrictions on NP VP constructions.

The following example (a) is an NP AP small clause construction.

| (a) | Louis considers (NP)Marie (AP)funny.[47] | |||

| Louis | considère | Marie | drôle. | |

| Louis | considers | Marie | funny. | |

The following example (b) is an NP PP small clause construction.

| (b) | Marie wanted (NP)Louis (PP)in her office.[47] | |||||

| Marie | voulait | Louis | dans | son | bureau. | |

| Marie | want+past | Louis | in | her | office. | |

The following example (c) is an NP VP small clause construction. The verb here is infinitival, without inflected tense, and takes a PP complement.

| (c) | Louis saw (NP)Marie (VP)play the bagpipe.[47] | ||||||

| Louis | voyait | Marie | jouer | de | la | cornemuse. | |

| Louis | see+past | Marie | to play | of | the | bagpipe. | |

However, the following example (d) is an NP VP small clause construction that is ungrammatical. Although the verb here is infinitival, it cannot grammatically take an AP complement.

| (d) | *I believe (NP)Jean (VP)to be sick.[7] | ||||

| *Je | crois | Jean | être | malade. | |

| I | believe | Jean | to be | sick. | |

Coordination tests in French do not provide consistent evidence for small clauses' constituency. Below is an example (e) proving small clauses' constituency. The two small clauses in this example use an NP AP construction.

| (e) | Louis considers (NP)Mary (AP)funny and (NP)Bill (AP)stupid.[47] | ||||||

| Louis | considère | [Marie | drôle] | et | [Bill | stupide] | |

| Louis | considers | Marie | funny | and | Bill | stupid | |

However, the example (f) below makes an incorrect prediction about constituency.

| (f) | Louis gave [a book to Mary yesterday] and [a painting to Barbara the day before].[47] | ||||||||||||||||

| Louis | a | donné | [un | livre | à | Marie | hier] | et | [une | peinture | à | Barbara | le | jour | d' | avant]. | |

| Louis | have | give+past | [a | book | to | Mary | yesterday] | and | [a | painting | to | Barbara | the | day | of | yesterday.] | |

Sportiche provides two possible interpretations of this data: either coordination is not a reliable constituency test or the current theory of constituency should be revised to include strings such as the ones predicted above.[47]

Brazilian Portuguese

In Brazilian Portuguese, there are two types of small clauses: free small clauses and dependent small clauses.

Dependent small clauses are similar to English in that they consist of an NP XP in a predicative relation. Like many other Romance languages, Brazilian Portuguese has free subject-predicate inversion, although it is restricted here to verbs with single arguments.[48] Dependent small clauses may appear in either a standard, as in example (a), or an inverted form, as in example (b).

| (a) | I consider (NP)the boys (AP)innocent.[49] | |||

| Considero | os | meninos | inocentes. | |

| consider-1SG | the-PL | boys | innocent-PL. | |

| (b) | I consider (NP)the boys (AP)innocent.[49] | |||

| Considero | (AP)inocentes | (NP)os | meninos. | |

| consider-1SG | innocent-PL | the-PL | boys. | |

In contrast, free small clauses can only occur in the inverted form. The small clause construction in example (c) has an XP NP construction, specifically an AP NP construction.

| (c) | How beautiful your house is![49] | |||

| (AP)Bonita | (NP)a | sua | casa! | |

| beautiful | the | your | house | |

However, in example (d), using an NP AP formation renders the free small clause ungrammatical.

| *(d) | How beautiful your house is![49] | |||

| (NP)A | sua | casa | (AP)bonita! | |

| the | your | house | beautiful | |

The classification of free small clauses is under debate. Some linguists argue that these free small clauses are actually cleft sentences with finite tense,[49] while other linguists believe that free small clauses are tense phrases without inflected tense on the surface.[50]

Balto-Slavic: Lithuanian

Lithuanian small clauses may occur in a NP NP or NP AP construction.

NP PP constructions are not small clauses in Lithuanian as the PP does not enter into a predicative relationship with the NP.[51]

The example (a) below is of an NP NP construction.

| (a) | Wilson proclaimed (NP)Cagan (NP)a nobleman.[52] | |||

| Wilsonas | paskelbė | Kaganą | bajoru. | |

| Wilson-NOM | proclaimed | Cagan | nobleman. | |

The example (b) below is of an NP AP construction. While the English translation of the sentence includes the auxiliary verb "was", it is not present in Lithuanian.

| (b) | The Supreme Court declared that (NP)the protest (was) (AP)well-founded.[53] | |||||

| Aukščiausias | teismas | pripažino | kad | protestas | pagrįstas | |

| Supreme | Court-NOM | proclaimed | that | protest-NOM | well-formed | |

In Lithuanian, small clauses may be moved to the front of the sentence to become the topic. This suggests that the small clause operates as a single unit, or a constituent. Note that the sentence in example (c) in English is ungrammatical so it is marked with an asterisk, but the sentence is grammatical in Lithuanian.

| (c) | *[(NP)Her (NP)an immature brat] he considers.[54] | ||||

| [Ją | nesubrendusia | mergiote] | jis | laiko. | |

| [Her-ACC | immature | brat] | he-NOM | considers. | |

The phrase her an immature brat cannot be split up in example (d), which provides further evidence that the small clause behaves as a single unit.

| (d) | *(NP)Her he considers (NP)an immature brat.[55] | ||||

| *Ją | jis | laiko | nesubrendusia | mergiote. | |

| *Her-ACC | he-NOM | considers | immature | brat. | |

Sinitic: Mandarin

In Mandarin, a small clause does not only lack a verb and tense, but also the presence of functional projections.[56] The reason for this is that the lexical entries for particular nouns in Mandarin not only contain the categorical feature for nouns, but also for verbs. Thus even with the lack of functional projections, nominals can be predicative in a small clause.[56]

| a. I consider him a student. | ||||

| 我 | 当 | 他 | 学生 | |

| Wǒ | dāng | tā | xuéshēng | |

| I | consider | him | student | |

| b. He is a student. | ||

| *他 | 学生 | |

| *tā | xuéshēng | |

| he | student | |

| c. He is Taiwanese. | |||

| 他 | 台湾 | 人 | |

| tā | taiwan | rén | |

| He | taiwan | -ese | |

(a) illustrates a complement small clause: it has no tense-marking, only a DP subject and an NP predicate. However, the semantic difference between Mandarin Chinese and English with regards to its small clauses are represented by example (b) and (c). Though (b) is the embedded small clause in the previous example, it cannot be a matrix clause. Despite having the same sentence structure, a small clause consisting of a DP and an NP, due to the ability of a nominal expression to also belong to a second category of verbs, example (c) is a grammatical sentence. This is evidence that there are more restrictive constraints on what is considered a small clause in Mandarin Chinese, which requires further research.[56]

Special case of small clause usage

Below is case of special usage of small clause used with the possessive verb yǒu. The small clause is underlined.

| Zhangsan is (at least) as tall as his older brother. | ||||

| 张三 | 有 | 他 | 哥哥 | 高 |

| Zhāngsān | yŏu | tā | gēgē | gāo |

| Zhangsan | have | his | older brother | tall |

Here, the possessive verb yǒu takes a small clause complement in order to make a degree comparison between the subject and indirect object. Due to the following AP gāo, here the possessive verb yǒu expresses a limit of the degree of tallness. It is only with a small clause complement that this uncommon degree use of the possessive verb can be communicated.[57]

Korean

Below is an example of a fully complemented clause and an embedded small clause in Korean. The small clause is bolded.

| John thinks that Mary is reliable. | |||||||

| 존 | 은 | 매리 | 가/를 | 미덥 | -다- | -고 | 생각한다 |

| John | un | Mary | ga/lul | mitep | -ta- | -ko | sangkakhanda |

| John | NOM | Mary | NOM/ACC | reliable | DEC | COMP | think.PRES.DECL |

| John thinks Mary reliable. | ||||||

| 존 | 은 | 매리 | *가/를 | 미덥 | -게 | 생각한다 |

| John | un | Mary | *ga/lul | mitep | -gye | sangkakhanda |

| John | NOM | Mary | *NOM/ACC | reliable | SC | think.PRES.DECL |

In the fully complemented clause, the sentence would be grammatical whether the object Mary is marked with a nominative case or an accusative case. However, as the subject of the small clause, the case marking for the object is strictly accusative. This demonstrates that raising-to-object is optional from a complete clauses and necessary from small clauses.[58]

See also

References

- Citko, Barbara (2011). "Small Clauses: Small Clauses". Language and Linguistics Compass. 5 (10): 748–763. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2011.00312.x.

- Balazs, Julie (2012-08-20). "The Syntax Of Small Clauses": 4. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Balazs, Julie (2012-08-20). "The Syntax Of Small Clauses": 5. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Williams, Edwin S. (1983). "Against Small Clauses". Linguistic Inquiry. 14 (2): 287–308. ISSN 0024-3892. JSTOR 4178326.

- Stowell, Timothy Angus (1981). Origins of phrase structure (Thesis thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. hdl:1721.1/15626. pg. 87-88.

- Balazs, Julie (2012-08-20). "The Syntax Of Small Clauses": 6. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Balazs, Julie (2012-08-20). "The Syntax Of Small Clauses": 7. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Al-Horais, Nasser (2013). "A Minimalist Approach to the Internal Structure of Small Clauses" (PDF). The Linguistics Journal. 7: 320.

- Small clauses. Cardinaletti, Anna., Guasti, Maria Teresa. San Diego: Academic Press. 1995. ISBN 978-0126135282. OCLC 33087681.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Kim, Jong-Bok (2013). "On the Existence of Small Clauses in English" (PDF). 영어학연구. 19: 67–88. doi:10.17960/ell.2013.19.1.004. S2CID 34737509.

- Kreps, Christian (1994). "Another Look at Small Clauses" (PDF). University College Working Papers in Linguistics. 6: 149–177.

- Kreps, Christian (1994). "Another Look at Small Clauses" (PDF). University College Working Papers in Linguistics. 6: 159.

- Bailyn, John (2001). "The Syntax of Slavic Predicate Case". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- Hornstein, Norbert; Lightfoot, David (1987). "Predication and PRO". Language. 63 (1): 33. doi:10.2307/415383. JSTOR 415383.

- Radford, Andrew (1988). "Small Children's Small Clauses". Transactions of the Philological Society. 86 (1): 8. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1988.tb00391.x. ISSN 1467-968X.

- Culicover, PW; Jackendoff, Ray (2005). Simpler syntax. Oxford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780199271092.

- Haegeman, Liliane; Gueron, Jacqueline (1999). English grammar : a generative perspective. Blackwell Publishers. pp. 109–111. ISBN 978-0-631-18838-4.

- Kubo, Miori (1993). "Are Subject Small Clauses Really Small Clauses?" (PDF). MITA Working Papers in Psycholinguistics. 3: 98.

- Sportiche, Dominique (1995). Cardinaletti, Anna (ed.). French Predicate Clitics and Clause Structure. Syntax and Semantics, Vol 28. 525 B Street, Suite 1900, San Diego, California: Academic Press, Inc. p. 289. ISBN 978-0126135282.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Bruening, Benjamin (2018-07-12). "Depictive Secondary Predicates and Small Clause Approaches to Argument Structure". Linguistic Inquiry. 49 (3): 537–559. doi:10.1162/ling_a_00281. ISSN 1530-9150. S2CID 57568932.

- Matthews, PH (2007). Syntactic relations : a critical survey. Cambridge University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780521845762.

- Tomacsek, Vivien (2014). "Approaches to the Structure of English Small Clauses" (PDF). The ODD Yearbook. 9: 128–154.

- Chomsky, Noam (1986). Knowledge of language : its nature, origin, and use. Praeger. p. 20. ISBN 9780275917616.

- Ouhalla, Jamal (1994). Introducing transformational grammar : from rules to principles and parameters. E. Arnold. p. 109. ISBN 9780340556306.

- Citko, Barbara (2011). "Small Clauses: Small Clauses". Language and Linguistics Compass. 5 (10): 751–752. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2011.00312.x.

- Citko, B (2011). "Small Clauses". Language and Linguistics Compass. 5 (10): 752. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2011.00312.x.

- Pereltsvaig, Asya (2008). Copular Sentences in Russian: A Theory of Intra-Clausal Relations. Springer Science. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-1-4020-5794-6.

- Citko, Barbara (2011). Symmetry in Syntax: Merge, Move and Labels. Cambridge University Press. pp. 176–178. ISBN 978-1107005556.

- Moro, Andrea. (2008). The anomaly of copular sentences. Unpublished manuscript, University of Venice.

- Williams, Edwin (Winter 1980). "Predication". Linguistic Inquiry (1 ed.). 11 (1): 204. JSTOR 4178153.

- Bowers, John (2001-01-01), "Predication", in Baltin, Mark; Collins, Chris (eds.), The Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, p. 310, doi:10.1002/9780470756416.ch10, ISBN 9780470756416

- Eide, Kristin M.; Åfarli, Tor A. (1999). "The Syntactic Disguises of the Predication Operator". Studia Linguistica. 53 (2): 160. doi:10.1111/1467-9582.00043. ISSN 0039-3193.

- Balazs, Julie E. (2012). The Syntax of Small Clauses. Masters Thesis, Cornell University.

- Chomsky, Noam (1970). "Remarks on nominalization". In Jacobs, Roderick; Rosenbaum, Peter (eds.). Readings in English Transformational Grammar. Georgetown University School of Language. pp. 170–221. ISBN 978-0878401871.

- Stowell, Timothy A. "Origins of phrase structure". hdl:1721.1/15626. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Contreras, Heles (1987). "Small clauses in Spanish and English". Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. 5 (2): 225–243. doi:10.1007/BF00166585. ISSN 0167-806X. S2CID 170111841.

- Bowers, J. (1993). The Syntax of Predication. Linguistic Inquiry,24(4), pg. 596-597. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178835

- Eide, Kristin M.; Åfarli, Tor A. (1999). "The Syntactic Disguises of the Predication Operator". Studia Linguistica. 53 (2): 160. doi:10.1111/1467-9582.00043. ISSN 0039-3193.

- Bailyn, J. F. (1995). A Configurational Approach to Russian ‘Free’Word Order. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Cornell University, Ithaca.

- Balazs, Julie E. (2012). The Syntax of Small Clauses. pg. 23. Masters Thesis, Cornell University.

- Basilico, D. (2003). The Topic of Small Clauses. Linguistic Inquiry,34(1), pg. 2. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4179219

- Citko, Barbara (2011). "Small Clauses: Small Clauses". Language and Linguistics Compass. 5 (10): 752. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2011.00312.x.

- Basilico, David (2003). "The Topic of Small Clauses". Linguistic Inquiry. 34 (1): 9. doi:10.1162/002438903763255913. ISSN 0024-3892. JSTOR 4179219. S2CID 57572506.

- Haegeman, Liliane (1994-06-08). Introduction to government and binding theory (2nd ed.). B. Blackwell. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-631-19067-7.

- Chomksy, Noam (1981). Lectures on government and binding : the Pisa lectures (7th ed.). Mouton de Gruyter. p. 107. ISBN 9783110141313.

- Wardhaugh, Ronald (2003). Understanding English grammar : a linguistic approach (Second ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-631-23291-9.

- Sportiche, Dominique (1995). Cardinaletti, Anna; Guasti, Maria Teresa (eds.). French Predicate Clitics and Clause Structure. Syntax and Semantics, Vol 28. 525 B Street, Suite 1900, San Diego, California 92101-4495: Academic Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0126135282.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Kato, Mary Aizawa (2007). "Free and depedent small clauses in Brazilian Portuguese". DELTA: Documentação de Estudos Em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada. 23 (SPE): 94, 95. doi:10.1590/S0102-44502007000300007. ISSN 0102-4450.

- Kato, Mary Aizawa (2007). "Free and depedent small clauses in Brazilian Portuguese". DELTA: Documentação de Estudos Em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada. 23 (SPE): 85–111. doi:10.1590/S0102-44502007000300007. ISSN 0102-4450.

- Sibaldo, Marcelo Amorim (2013). "Free Small Clauses of Brazilian Portuguese as a TP-Phrase" (PDF). Selected Proceedings of the 16th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium: 324, 336.

- Giparaitė, Judita. (2010). The non-verbal type of small clauses in English and Lithuanian. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Pub. p. 16. ISBN 9781443818049. OCLC 828736676.

- Giparaitė, Judita. (2010). The non-verbal type of small clauses in English and Lithuanian. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Pub. p. 90. ISBN 9781443818049. OCLC 828736676.

- Giparaitė, Judita. (2010). The non-verbal type of small clauses in English and Lithuanian. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Pub. p. 114. ISBN 9781443818049. OCLC 828736676.

- Giparaitė, Judita. (2010). The non-verbal type of small clauses in English and Lithuanian. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Pub. p. 117. ISBN 9781443818049. OCLC 828736676.

- Giparaitė, Judita. (2010). The non-verbal type of small clauses in English and Lithuanian. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Pub. p. 118. ISBN 9781443818049. OCLC 828736676.

- Wei, Ting-Chi (2007). "Nominal Predicates in Mandarin Chinese" (PDF). Taiwan Journal of Linguistics. 5 (2): 85–130.

- Xie, Zhiguo (2014). "The degree use of the possessive verb yǒu in Mandarin Chinese: a unified analysis and its theoretical implications". Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 23 (2): 113–156. doi:10.1007/s10831-013-9113-3. ISSN 0925-8558. JSTOR 24761412. S2CID 120969259.

- Hong, Sungshim; Lasnik, Howard (2010). "A note on 'Raising to Object' in small clauses and full clauses". Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 19 (3): 275–289. doi:10.1007/s10831-010-9062-z. ISSN 0925-8558. S2CID 122593799.

Literature

- Aarts, B. 1992. Small clauses in English: the non-verbal types. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Borsley, R. 1991. Syntactic theory: A unified approach. London: Edward Arnold.

- Chomsky, N. 1981. Lectures on government and binding: The Pisa lectures. Berlin:Mouton de Gruyter.

- Chomsky, N. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Culicover, P. 1997. Principles and parameters: An introduction to syntactic theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Culicover, P. and R. Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Haegeman, L. 1994. Introduction to government and binding theory, 2nd edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Haegeman, L. and J. Guéron 1999. English grammar: A generative perspective. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

- Matthews, P. 2007. Syntactic relations: A critical survey. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ouhalla, J. 1994. Transformational grammar: From rules to principles and parameters. London: Edward Arnold.

- Wardhaugh, R. 2003. Understanding English grammar, second edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.