Southern California Rapid Transit District

The Southern California Rapid Transit District (almost always referred to as RTD or rarely as SCRTD) was a public transportation agency established in 1964 to serve the Los Angeles metropolitan area. It was the successor to the original Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA). California State Senator Thomas M. Rees (D-Beverly Hills) sponsored the bill that created the RTD, which was meant to correct some deficiencies of the LAMTA,[2][3][4] and took over all of the bus service operated by MTA on November 5, 1964.[5][6] RTD was merged into the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 1993.

RTD logo from 1980 to 1993 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Los Angeles |

| Transit type | Bus Metro Rail |

| Number of lines | 190 Bus routes (1989)[1] 2 Metro Rail (1993) |

| Number of stations | 22 Metro Rail (1993) |

| Daily ridership | ?? (Weekdays) |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | November 5, 1964 |

| Ended operation | April 1, 1993 |

| Operator(s) | Southern California Rapid Transit District |

| Technical | |

| System length | Bus – 0 miles (0 km) (1993) Metro Rail – 26.5 miles (42.6 km) (1993) |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) (standard gauge) |

Creation

RTD was created on August 18, 1964, to serve the urbanized Southern California region, including Los Angeles County, San Bernardino County, Orange County, and Riverside County. RTD replaced the major predecessor public agency, the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority, and took over eleven failing other bus companies and services in the Southern California region.[7] RTD was placed in charge of creating a heavy rail public transportation system for Southern California, and for planning for bus improvements. In 1974, the El Monte Busway was opened, a bus-only lane (later converted to a high-occupancy vehicle lane). In 1973, RTD shed parts of its operations outside of Los Angeles County, (they were taken over by other agencies including what was then the new Orange County Transit District (now Orange County Transportation Authority) although it continued to operate inter-county service to Riverside and San Bernardino until the formation of LACMTA, and continues to operate a line (460 express) to Disneyland in Orange County and one route (161 local) that serves Thousand Oaks, California, in Ventura County.

Downtown Terminal

From 1967 until 1982, RTD operated a main downtown terminal in the basement of the Greyhound bus terminal at 6th and Los Angeles Streets. Greyhound used it until 1991, when they moved to their current terminal on 7th St. Because of the positioning of mirrors in the single entrance/exit ramp, buses entered the ramp and drove in on the left hand side of the ramp (standard American practice is to drive on the driver's right side of the road or on a ramp), where at the bottom, a display lamp would indicate which of the 15 berths the bus was to terminate at. The driver would then turn left and go around the bus berthing area, which was in the center of the terminal. This prevented buses from ever having a danger of collision as the buses would always travel through the terminal in a clockwise direction, whereas in standard American traffic, vehicles drive on the right and a traffic circle or "roundabout" has traffic moving counterclockwise.

The terminal also had a rule, indicated on all signs leading to the bus berths, that cash payments were not accepted on buses in the terminal; a person had to either have a monthly pass or purchase tickets on the ground floor (one floor above the bus area). Tickets were standard paper coupons with amounts of 10¢ to $1.00, and could be purchased at any time, not merely when one was taking a bus. Tickets were accepted on all RTD routes at all times, and could also be purchased at various locations around the region, although RTD buses accepted cash everywhere, except when departing from the downtown terminal.[8]

RTD eventually discontinued use of the Greyhound bus terminal in the late 1980s, and resumed having connections for buses on the various streets in the downtown area.

A similar practice occurred in Long Beach for the small number of routes that left its downtown area. RTD operated a small office on Ocean Boulevard, required tickets to be purchased, either there or in advance, and prohibited acceptance of cash payment for buses leaving the stop in front of its Long Beach downtown terminal. When the City of Long Beach introduced the consolidated transit mall, RTD discontinued the use of its own terminal, and allowed persons to pay cash on buses leaving the downtown Long Beach Transit Mall.[8]

Animosity

RTD was essentially the "800 pound gorilla" as far as public transportation in Southern California was concerned. In a 1983 video created by RTD, the District stated its operating service area was larger than that of the transit systems of Miami, Buffalo, Atlanta, Baltimore and Washington, D.C. combined.[9]

RTD operated all service in the city of Los Angeles, and operated some service to neighboring cities. Many of the local bus agencies operating in the county (all of them either owned by a municipality or operated on its behalf) either had a "live and let live" or an out-and-out hostile relationship with RTD. One of the more serious rivalries was between Long Beach Transit and RTD. RTD had wanted to take over all or part of the operation of Long Beach Transit. However, it was considered that RTD would probably stick to covering the major areas ("cream skimming") and might let service languish in the less profitable areas, as witness some of the problems that some of the poorer areas in Los Angeles (such as Watts) had had in getting reasonable bus service. As a result of the animosity, a kind of pettiness grew between the two agencies. One example of which is, of all the bus lines which operated in Los Angeles County: Long Beach, Norwalk, Cerritos, Torrance Transit, City of Santa Monica, Culver City Municipal Transit, Orange County Transit, and RTD, all of these agencies would allow any of the other's employees to deadhead free, if in uniform (or had identification issued by their agency), except that RTD and Long Beach would not allow each other's drivers to ride free on their buses.[8]

Generous Employee Benefit

One benefit that RTD offered, which no other bus line in the region offered, was the very generous practice that, in addition to RTD employees being allowed to ride free on RTD buses (and as noted above, every other bus transit operator except Long Beach), their spouse and all children under 18 were also given free passes.[10]

Restrictions and expansion

Two features of transportation in Southern California were the local restriction and the Long Beach South of Willow prohibition.

The local restriction prohibited any private carrier such as Greyhound or Continental Trailways from selling one way or round-trip bus tickets between any two points within the same area that RTD operated. For example, Greyhound sold a ticket for transport between Long Beach and the Magic Mountain amusement park (now Six Flags Magic Mountain) in Valencia, and the customer could optionally purchase admission to the park on the same transport ticket. This required the customer to change buses in Downtown Los Angeles to the bus bound for Valencia, and vice versa on return, but Greyhound could not directly sell a ticket for travel between Long Beach and Los Angeles, unless the person was traveling outside RTD's service area.

The South of Willow prohibition occurred because of the dispute between RTD and Long Beach Transit, wherein only Long Beach Transit was permitted to pick up passengers within the City of Long Beach south of Willow Street for transport to any other place in the city that was also south of Willow. RTD (and all other transit agencies except Long Beach Transit) were prohibited from providing a pick up and drop off both south of Willow Street. Generally, any pickup anywhere in the city which was south of Willow either had to be for transportation north of Willow Street or outside of the city. Buses which traveled into the area south of Willow Street could only discharge passengers, and could not pick up any passengers until they resumed travel either north of Willow or outside of Long Beach, and such passengers could not exit the bus until north of Willow or outside the city. On Long Beach Boulevard, for example, RTD was not allowed to discharge any northbound passengers anywhere on Long Beach Boulevard south of Willow Street. Buses going southbound were to be "discharge only" south of Willow, and were to be "embark only" going northbound if south of Willow Street.

Over the years, RTD made a number of strategic purchases and trades to extend service. The original bus line operating between Long Beach and Santa Monica was operated by Western Greyhound Lines from 1923 until it was acquired by RTD in 1974.[11] RTD broke the line in half, kept the portion running from Long Beach to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), then took the portion from Los Angeles International Airport to Santa Monica and sold or traded it to the City of Santa Monica Municipal Bus line in exchange for the right to run buses from Downtown Los Angeles into Santa Monica. As a result, persons traveling from Long Beach to Santa Monica would take an RTD bus from Long Beach to LAX, then transfer at the airport to a Santa Monica Municipal bus.[8]

Transfers

All of the transit agencies in the county issued local transfers (a transfer from one of their lines to another). Most issued the same transfer blank for every bus on their route, where they just issued a single transfer where the driver punched in the route number, possibly the direction of travel (to prevent people who were taking short trips from getting on a bus going back where they came from without paying for the return trip) and the month and day. Long Beach issued a specific transfer preprinted with the specific route number. But RTD issued a new transfer every day, so that the transfer would have "Mon Nov. 27 1978" preprinted on transfers issued on that day.

Another different practice involved the issuance of "interagency transfers" where a rider was switching between one bus line (bus company) and another, e.g. Torrance Transit to Orange County Transit. RTD issued one transfer, which was good locally on its own system for all of its bus routes and functioned as an interagency transfer for credit toward the fare on a different bus line. All other bus lines issued an "interagency transfer" different from their own local transfers. It was believed that the reason for this was that RTD actually printed the interagency transfers and sold them to all the other bus lines. In the early 1980s, Long Beach Transit would also break from this system, and would have ticket printers installed on every bus to issue both local (Long Beach Transit-based) and interagency transfers (drivers would, in case the printer failed, keep a book of Long Beach and standard interagency transfer for just such emergencies.)

For a six-month period during the middle 1970s, RTD, and possibly other transit agencies in the county, received a massive subsidy, cutting prices for bus trips from 60¢ to $1.25, depending on the route, to 25¢ on weekdays and Saturday, and 10¢ on Sunday, for all trips anywhere within Los Angeles County. Trips outside the county remained the regular price. During this period, all transit agencies in the county discontinued issuing transfers. When the subsidy ended, prices returned to the original amounts, and RTD resumed issuing transfers.[8]

Renumbering

Bus routes in the county originally had various identifications. The route from Long Beach to Los Angeles, which operated most of the route as an express service along the freeway of former California State Route 7 (now Interstate 710), was known as the 36F (for "Freeway Flyer"). Other routes had various numbers that at times seemed somewhat random, as they were added to the system when RTD had absorbed earlier systems—for example, routes 107, 108, 109, and 110 were in the Pasadena area, as they had been originally part of Pasadena City Lines, while routes 106 and 111 were elsewhere in RTD's system. In the mid-1970s, RTD began to group their routes by region—for example, routes in the 400s (such as 423, 434, and 496) served primarily the San Gabriel Valley, while those in the 800s (801 or 829, for example) served the southern Los Angeles County area. In addition to renumbering, most of the routes were modified into a more logical grid system, following major thoroughfares and moving route termini to near other routes to allow for efficient transfers. In theory, most residences were no more than a quarter-mile away from any bus route.

In 1983, RTD would institute a new, massive renumbering system, while keeping the earlier grid pattern. The new numbering system is as follows:

- Routes 1-99 — Buses which ran locally into downtown Los Angeles

- 100-199 — Buses which ran primarily east and west, but not into downtown

- 200-299 — Buses which ran primarily north and south, but not into downtown

- 300-399 — Buses operating limited service

- 400-499 — Buses which ran express into downtown Los Angeles

- 500-599 — Express buses not running to downtown

- 600-699 — Special Service not running to downtown

As a result of the renumbering, the 36F became the 456. The local bus running from Long Beach to downtown Los Angeles became the 60. The bus from Long Beach to LAX changed from 66 to 232.[12] The local route from Pasadena to Pomona, numbered in the 1970s as route 440, became route 187, while a parallel route (numbered 434) that went from City of Hope in Duarte west through Monrovia, Arcadia, Pasadena (to JPL), La Canada Flintridge, then to downtown Glendale, was renumbered 177.

Probably due to the success RTD had in clarifying where its routes went by the renumbering, Long Beach Transit would also change its numbering system as well. Foothill Transit would also keep the line numbers that it inherited from RTD, and later from the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Los Angeles County Transportation Commission

The Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (LACTC) was formed in 1976 resulting from the requirement that all counties in the state form local transportation commissions. Its main objective was to be the guardian of all transportation funding, both transit and highway, for Los Angeles County. The creation of the LACTC required RTD to share some of its power. The governing structure of the LACTC was similar to that of the SCRTD, however, the city of Los Angeles had three of the eleven board members, compared to two on the SCRTD board). By law, the commission included the mayor of Los Angeles, a city council member appointed by the mayor, a private citizen appointed by the mayor, all five county supervisors, a member of the city council of Long Beach and two city council members from other municipalities, elected by the Los Angeles branch of the California League of Cities. Each of the members had an appointed alternate.

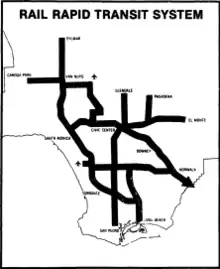

Metro Rail

In 1980 voters passed Proposition A, a half-cent sales tax for a regional transit system. The measure succeeded after proposals in 1968 and 1974 had failed. The map that accompanied the initiative showed ten transit corridors [13] with the Wilshire subway line the "cornerstone" of the system, according to former SCRTD planning director Gary Spivak. Los Angeles County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn was the author of the proposition, declaring, "I'm going to put the trains back."[14] The Los Angeles County Transportation Commission's first light rail line was on the old Long Beach Red Car route from Los Angeles to Long Beach, which passed through Hahn's district (this would become the Metro Blue Line). Caltrans surveyed the condition of former Pacific Electric lines in 1982.[15]

On September 11, 1985, U.S. Representative Henry Waxman added an amendment to that year's Federal Transportation Budget removing all subway construction funds, citing safety concerns after an unrelated methane explosion in the Fairfax District.[16]

By 1986, due in part to last-minute lobbying by RTD president Nick Patsaouras, a compromise was reached between Waxman and Representative Julian Dixon. The deal allowed funding to go through as long as it did not pass through the Wilshire corridor. With a Wilshire corridor alignment prohibited, the Metro Red Line was reprioritized and routed north up Vermont, the next highest projected ridership corridor, to Hollywood. Because of the change in alignment, a 1-mile (1.6 km) stub line on Wilshire between Vermont and Western persists[17][18] until the Purple Line Extension is opened in 2023.

On October 27, 2005 an independent group of experts stated that there was no significant problem with methane explosion.[19] Congressman Waxman then proposed legislation to lift the federal ban on subway construction in the Wilshire Corridor, which passed. By 2007, this lifting of the ban, along with several other factors such as traffic congestion, lessening racial prejudice, increasingly progressive and environmental attitudes, have rekindled interest in what has come to be known as the Metro Purple Line.[20][21]

However, a separate measure passed locally in Los Angeles has prohibited use of Metro's local sales tax revenue on "new subway construction". This has deterred Metro from building underground, although the Metro Gold Line Eastside Extension light rail has a 1.8-mile (2.9 km) segment where it runs underground.

In the following years, several light rail and subway lines were opened. In 1990, the RTD opened the Metro Blue Line, the region's first modern light rail line. In 1993, the first segment (known as MOS-1 for Minimal Operable Segment 1)[22] of the heavy rail Red Line opened, running from Union Station to MacArthur Park. Three years later, the Red Line was extended to Wilshire/Western in Koreatown.

RTD pioneered experimenting with alternate fuel buses in what the Transit Coalition derisively called "the fuel of the month club."[23] At the start of Metro's existence, there were buses running on ethanol, methanol, regular diesel, low-sulfur (clean) diesel, and CNG. Battery-operated buses and trolleybuses were proposed but never operated in regular service.[24]

Merger

The successor agency to RTD is the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority ("LACMTA"). LACMTA is the product of the merger of RTD and the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (LACTC).

RTD and LACTC officially merged on April 1, 1993.[25] Initially, the agency retained the locations of the predecessor agencies in Downtown Los Angeles, but later moved to the 25-story Gateway Plaza Building adjacent to historic Union Station in 1995. In the wake of local media reports of expensive Italian marble used in its construction, the structure was derisively dubbed the Taj Mahal.[26] Housed within the building is the Dorothy Gray Transportation Library, a comprehensive collection of transportation-related books, videos, and other materials, said to be one of the largest in the nation. The library is open to the public.

References

- Peterson, Neil & Pegg, Alan F. (November 30, 1990). Systems Report on Passenger Overcrowding on Los Angeles County Bus Services (PDF). LACTC/SCRTD Joint Policy Board (Report).

Schedule adjustments are made regularly to SCRTD's 190 routes

- RTD was established as a public corporation by Section 30000 etc. of the California Public Utilities Code

- "Brown Signs Bill Creating New Rapid Transit District: Steps to Replace MTA Will Start Aug. 18; Board to Study Early Bond lssue". Los Angeles Times. May 14, 1964. p. A1. Alternate Link via ProQuest.

- Hebert, Ray (August 17, 1964). "Los Angeles Looking Ahead to New Rapid Transit Era: Legislature Gives Tools to Planners So They Can Build Complete System". Los Angeles Times. p. A1. Alternate Link via ProQuest.

- Hebert, Ray (October 1, 1964). "Pomona Mayor Named Rapid Transit Leader: New District Board Starts Organizational Groundwork Prior to MTA Takeover Nov. 5". Los Angeles Times. p. A12. Alternate Link via ProQuest.

- "New Agency Takes Over From MTA: Rapid Transit Planners Pledge Solution to Crisis". Los Angeles Times. November 6, 1964. p. OC1. Alternate Link via ProQuest.

- metro.net history. Retrieved April 4, 2004. Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Robinson, Paul (January 9, 2012). "Remembering RTD and the "good old days" of cheap LA area public transit". Stories, Parables and Long Items (blog).

- "Southern California RTD: Meeting the Challenges", RTD, 1983, available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKtixeeJrJk (Retrieved February 2, 2016)

- Fringe Benefits for RTD Employee Families Not Available for Long Beach Transit, Long Beach California Independent-Press Telegram, June 5, 1982, Page A-6

- "Los Angeles Transit History". Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on 2014-10-10. Retrieved 2014-09-20.

- Los Angeles Transit Routes Retrieved October 19, 2007. Archived August 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Southern California Rapid Transit District". The Electric Railway Historical Association of Southern California. Retrieved April 4, 2006.

- Berkowitz, Eric (August 18, 2005). "The Subway Mayor". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- "1981 Inventory of Pacific Electric Routes" (PDF). Caltrans. February 1982. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Rep. Henry Waxman - Issues and Legislation - Los Angeles Metro Rail. Waxman, Henry. Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Metro riders guide". Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on January 24, 2007.

- Connell, Rich (January 9, 1986). "RTD Unveils New Metro Rail Plans : More Debate Expected Over Routes Designed to Skirt Gas-Danger Areas". Los Angeles Times.

- "American Public Transportation Association, Review of Wilshire Corridor Tunneling, Los Angeles, California, October 24–27, 2005" (PDF). The Transit Coalition (lobby group).

- Bottleneck Blog : Los Angeles Times : Wilshire subway cheerleading Archived May 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Rep. Henry Waxman - Issues and Legislation - Los Angeles Metro Rail Archived November 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Los Angeles (MOS-3 Segments of Metro Rail)". Archived from the original on March 13, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2007. Federal Transit Administration - Planning & Environment Federal Transit Administration. Retrieved August 10, 2006.

- "Criswell Predicts." The Transit Coalition. "2007: The Year in Transit". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- "Electric Trolleybuses for the LACTMA's Bus System" (PDF). Areli Associates. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007.

- Klugman, Mark. Brief Report: L.A.’s Transit Policing Partnership. Spring 1998. Retrieved April 4, 2006 Archived December 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Simon, Richard (September 24, 1995). "Urban jewel or height of folly? Lavish new transit center and 26-story office tower next to Union Station will become a civic treasure, MTA officials predict". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.