St Carantoc's Church, Crantock

St Carantoc's Church, Crantock is in the village of Crantock, Cornwall, England. Since 1951 the church has been designated as a Grade I listed building.[1] It is an active Anglican parish church in the diocese of Truro, the archdeaconry of Cornwall and the deanery of Pydar. Its benefice is combined with that of St Cubert.[2]

| St Carantoc's Church, Crantock | |

|---|---|

St Carantoc's Church, Crantock | |

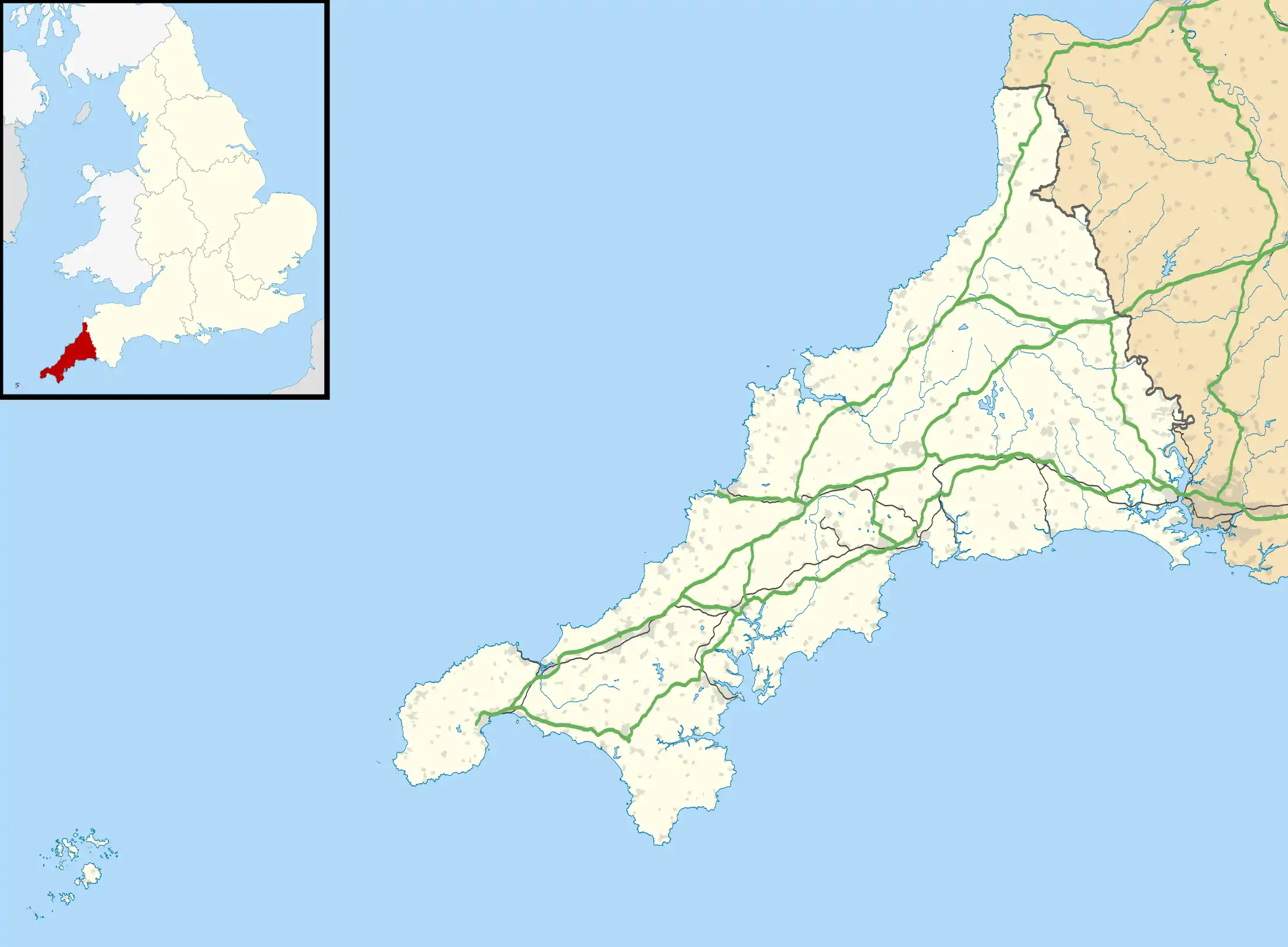

St Carantoc's Church, Crantock Location in Cornwall | |

| OS grid reference | SW 790 605 |

| Location | Crantock, Cornwall |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | St Carantoc, Crantock |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Dedication | St Carantoc |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 24 October 1951 |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Norman, Gothic |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Slatestone and granite rubble with granite dressings Slate roofs |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Crantock |

| Deanery | Pydar |

| Archdeaconry | Cornwall |

| Diocese | Truro |

| Province | Canterbury |

History

A church existed on the site before the Norman Conquest, dating from the time of St Carantoc in the 6th century.[3] Domesday Book (1086) recorded Crantock as held by the Canons of St Carantoc's; they had already been in possession before 1066.[4] The earliest features of the existing church are Norman. In 1224 the choir was reconstructed and a tower was added. A collegiate church was founded on the site by Bishop William Briwere of Exeter in the mid 13th century. This consisted of a Dean and nine prebendaries. To this collegiate church were appropriated the parishes of Crantock and St Columb Minor; in 1283 Bishop Peter Quinel united the prebends to make a vicarage. The vicar was assisted by a curate at St Columb Minor. However the old arrangement was restored by Bishop Stapeldon in 1309 and thenceforward the dean alone had cure of souls of both parishes, while the prebendaries were probably non-resident. In 1312 the Pope gave the deanery to a Frenchman; the cure of souls however was entrusted to a perpetual vicar while the Dean was absent. The endowment of the college was inadequate from the beginning but the economic effect of the Black Death made things worse. Bishop Grandisson in 1351 reconstituted the college as a dean, nine canons and four vicars choral (there had formerly been seven). Canons who were unwilling to reside could compound for non-residence by paying for the education of two clerks and two or three boys. In 1384 it was found that none of the canons was resident and that the dean was a pauper. In 1377 the church was seriously in need of repair; the canons had the transepts repaired but the parishioners were unable to repair the tower. A legacy of £20 was left by Bishop Brantyngham to this end in 1393 but not long afterwards the tower collapsed upon the nave so that it was ruined. Indulgences were sold in 1412 to raise funds and then a new tower was built at the west end.[5] In 1412 the tower collapsed and was rebuilt.[6] A memorial brass in Tintagel Parish Church commemorates Joan (d. 1430s?), mother of John Kelly who was vicar of Tintagel 1407-1427 and afterwards dean of Crantock.[7]

Following the dissolution of the monasteries the college was closed.[8] It then consisted of a dean, nine prebendaries and four vicars choral (viz. the curates of Crantock and St Columb Minor, the mass chaplain and the college clerk. Over three centuries of neglect was to follow; the curates were paid only £8 p.a. while all the tithes were received by the patrons. However the Bullers when they were patrons allowed the curates to have the vicarial tithe. In the 18th century the roofs and windows were restored. Crantock reached its nadir in the 19th century when the church was virtually a ruin. However Victorian restoration in the late 19th century and another restoration between 1902 and 1907 by Edmund H. Sedding (when he died in 1921 Sedding was buried in the churchyard) resulted in "the best adorned church in Cornwall" (Charles Henderson, writing in 1925).[1][5]

Architecture

Exterior

The church is built in slatestone and granite rubble with granite dressings and slate roofs. Its plan consists of a west tower, a nave with north and south aisles, north and south transepts, a chancel and a south porch. The tower is in three stages, with each stage being set back and angle buttresses up to the second stage. The parapet is corbelled and embattled. The tower has a west doorway above which is a 19th-century Perpendicular style window. On the south side of the second stage is a clock face. The interior of the church has plastered walls and a slate floor. The arcades contain some Norman architecture. In the west wall of the north transept is a blocked 12th-century doorway.[1]

Interior

In the south aisle is a piscina dating from the 19th century. The font dates from the 12th century. The communion rail dates from the 17th century and the wooden pulpit from the 19th century. The stained glass is from the 19th century although there are fragments of medieval glass in the sacristy.[1] The rood screen dates from 1905 and was carved by Mary Rashleigh Pinwell.[8] The church plate includes a silver chalice dated 1576. The parish registers date from 1559.[6] There is a ring of six bells. Three of these are dated 1767 by John III and Fitzantony II Pennington and the other three were cast in 1904 by John Taylor and Company.[9]

External features

In the churchyard are a number of objects which are listed at Grade II. These include a medieval stone coffin,[10] and four monuments.[11][12][13][14] Also in the churchyard are a granite cross dating from the 19th century which is set on a granite base probably dating from before the Norman Conquest,[15] and stocks dating from the 17th century which are set under a 20th-century gabled roof on granite piers.[16] The lychgate at the south entrance to the churchyard dates from the late 19th century.[17]

References

- Historic England, "Church of St Carantoc, Crantock (1327391)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

- St Carantoc, Crantock, Church of England, retrieved 18 October 2009

- Lives of the Cambro British Saints, p. 396, 1853, Rev. William Jenkins Rees

- Thorn, C. et al., ed. (1979) Cornwall. Chichester: Phillimore; entry 4,25

- Cornish Church Guide (1925) Truro: Blackford; pp. 78-80

- Crantock Church, Cornwall, Cornwall Calling, retrieved 19 January 2008

- Dunkin, E. (1882) Monumental Brasses. London: Spottiswoode

- Sackett, Eliza (ed.) (2006), British Churches, London: Bounty Books, p. 9, ISBN 0-7537-1442-6CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Crantock S Carantoc, Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers, retrieved 13 August 2008

- Historic England, "Coffin in the churchyard about 7 metres south of south aisle of Church of St Carantoc, Crantock (1137273)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

- Historic England, "George monument in the churchyard about 23 metres south of nave of Church of St Carantoc, Crantock (1312396)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

- Historic England, "Johns monument in the churchyard about 30 metres southeast of chancel of Church of St Carantoc, Crantock (1144153)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

- Historic England, "Martyn monument in the churchyard about 25 metres southeast of chancel of Church of St Carantoc, Crantock (1144154)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

- Historic England, "Unidentified monument in the churchyard about 5 metres south of nave of Church of St Carantoc, Crantock (1144152)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

- Historic England, "Cross in the churchyard of Church of St Carantoc, Crantock (1327372)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

- Historic England, "Stocks in the churchyard about 3 metres north of north transept of St Carantoc, Crantock (1327392)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

- Historic England, "Lychgate at the south entrance to the churchyard of St Carantoc, Crantock (1137281)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 13 October 2013

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Carantoc's Church, Crantock. |