St Illtyd's Church, Llantwit Major

St Illtyd's Church is a church complex in Llantwit Major, Vale of Glamorgan, southeast Wales. It is located at the site of the oldest college in the United Kingdom, Cor Tewdws, which was founded c. 395 AD in honour of the Roman Emperor Theodosius I. It was refounded by St. Illtud c. 508 AD, from whom it derives its name. The current church building was built in the 11th century by the Normans, with portions being rebuilt in the 13th and 15th centuries. The church building is one of the oldest and best-known parish churches in Wales. It is a grade I listed building, or building of exceptional interest, and has been called both the "Westminster Abbey of Wales"[1] for its unique collection of carved stones and effigies, and "the most beautiful church in Wales."[2]

The parish is currently part of the Rectorial Benefice of Llantwit Major in the Diocese of Llandaff.

History

First College of Theodosius

In 380 AD, the Roman emperor Theodosius I proclaimed Christianity to be the only legitimate religion of the Roman Empire, ending imperial support for traditional polytheistic religions and customs.[3] A college honouring him was established at this site in the c. 395 AD. According to legend, Theodosius founded the college himself, however, there is not any clear evidence that Theodosius was ever actually present at the site. The college was the earliest school, former or extant, in all of Great Britain, and has even been called "the oldest college in the world."[4] It was founded during the twilight of the Roman occupation of Britain, and after the withdrawal of the Roman legions c. 409 – 410 AD, Britain was raided by the Irish, Scots, and Picts, who sacked villages and monasteries, and carried off the inhabitants as slaves. The College of Theodosius was reputedly burnt to the ground by Irish pirates in 446 AD, and was abandoned.[5]

Some sources claim that St. Patrick was kidnapped from the college when it was sacked,[5] though this is probably a later fabrication[6] that may be attributed to Iolo Morganwg, as the original source for this information comes from the disputed Iolo MSS. Further, as A. C. Fryer points out, St. Patrick's own confession states that he was only 16 when he was kidnapped, making him too young to be a principal at the college.[6]

St. Illtud's School, Bangor Tewdws

The site of the college lay barren for 62 years, until it was re-established by St. Illtud c. 508. According to the Book of Llandaff, St. Dubricius commissioned Illtud to re-establish the college,[7] and the place came to be known as Llanilltud Fawr, meaning "Illtud's Great Church" (Welsh: llan, church enclosure + Illtud + mawr, great). The school came to be known in Welsh by a variety of different names, including Bangor Tewdws (College of Theodosius), or later Bangor Illtyd ("Illtyd's college").[8] This college was most likely built of wood or wattle and daub.[8] According to tradition, the college became very successful, and a number of Celtic saints studied there, including Saint David, Saint Samson, Saint Paul Aurelian, Gildas the Historian, Saint Tudwal, Saint Baglan and king Maelgwn Gwynedd. At one time, the college was said to have seven halls and over 2000 students, though the main source for these numbers comes from the Iolo MSS, manuscript[9] which may have been forged by Iolo Morganwg. The ruins of the school are believed to be in a garden on the north side of the churchyard, and the monastery was situated north of the tithe barn on Hill Head.[10]

The Norman Invasion

The college is believed to have been attacked by the Danes in 987, but it was the Normans who brought the greatest change to the college. In the 11th century, Glamorgan was conquered by Robert Fitzhamon. Fitzhamon was a Norman noble, and it is thought that he attacked Glamorgam by sea c. 1080,[11] conquering it and bringing it under the power of the Marcher Lords. During the conquest, the wooden college and church were destroyed, and its endowments were transferred to newly established Tewkesbury Abbey, Fitzhamon's personal project. For a while, the church even lost its right of sanctuary, which was not restored until 1150 by the Bishop of Llandaff.[12] The Normans eventually rebuilt a parish church on the ruins of the old college c. 1100, but the college was greatly diminished in size and importance.

13th century rebuilding

In the 13th century, the parish church underwent major renovations: A low tower was added to the east end, and a second chapel was built adjoining the first one, sharing a wall in the center of the church.[13] The old western chapel continued to be used as a parish church, but the new eastern chapel was used by the monastic community.[2] Later in the century, an extensive grange or farm was established on land to the west of the church.[13] The newer church was built by Richard Neville.[8]

15th Century rebuilding

Around 1400, the East monastic church was extended with side aisles, and the roof and tower were raised to their current heights.[13] The church was also fitted with new roof, made of fine, Irish bog oak, and the church was fitted with a number of different murals and carvings.[2][13] A chantry, now known as the Galilee chapel, was also endowed by Sir Hugh Raglan as an extension to the West chapel.[13]

Dissolution of the Monasteries and afterwards

In the 16th century, during the dissolution of the monasteries, the monastic community was disbanded, and the East chapel was adopted as the parish church. During the dissolution and the later Puritan period, the medieval grange declined, and the interior church fell into disrepair, and many of the murals and statues were destroyed.[13] The West chapel fell into disuse, and served mainly as a repository for church artefacts. It wasn't restored or put back into regular use until the beginning of the 20th century.

Church Architecture

The elongated church (51.4081°N 3.4878°W) is a conglomeration of distinct buildings, and is divided into two areas by a wall: the east chapel, a 13th-century monastery church, and the west chapel, a Norman parish church. The grounds also include a 13th-century gatehouse, a monks' pigeon-house, ruined walls in a garden area, and mounds near the vicarage.[8]

The West Chapel

The West chapel church is a 40.5 feet (12.3 m) lady chapel,[10] and was built in the Romanesque style popular with the Normans in the 12th century. It was a simple cruciform church, and there is considerable evidence that it was built on the foundation of an earlier church that might have dated from St. Illtud's period.[13] It was intended to be used as a parish church, and it is the oldest standing portion of St. Illtyd's Church.[2] This portion of the church was particularly neglected after the dissolution of the monasteries, and wasn't restored until the early years of the 20th century.[13]

The church contains a curfew bell and medieval priest effigies.[14] There is also an inscription to King Rhys ap Arthfael of Morgannwg who died in the mid-9th century.[8] The West chapel is still used for worship, and is also a depository for many historical artifacts.[13]

The East Chapel

Architectural features of East church include squints (hagioscopes), stone benches, a carved stone reredos, and roof level markings on the tower, which tell the story of development in the East church.[13] Other features of interest in the East chapel are the medieval wall paintings, which include the Royal Standard of King James c. 1604, St. Christopher (c.1400) and those of Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary on the walls of the Chancel.[13]

The Galilee Chapel

The Galilee chapel was built on the western end of the West chapel during the 13th century, and was positioned near the sacristy, where the vestments and church plate were stored.[15] Though its original purpose is unknown, it was endowed as a chantry by Sir Hugh Raglan in around 1470–80.[16] When Parliament abolished chantries during the reign of Edward VI, the Galilee chapel fell into a ruined state for many centuries.[2] In 2013, after two years of fundraising, the Galilee Project successfully raised funds to reconstruct the chapel and bring it back into use as a visitor's centre and exhibition centre for the Celtic crosses.[17] The chapel was rededicated and reopened in November, 2013.[18]

Galilee Chapel Renovation

Project History

After the dissolution of the chantries during the reformation, the Galilee chapel fell into disrepair, and was in ruins for nearly 400 years. It wasn't until 1963 that the then vicar began thinking about the possibility of refurbishing the building.[19] In 2006,[19] A committee was formed for the purpose of advancing the rebuilding of the chapel as a space dedicated to displaying the Celtic stones and telling the story of Christianity as it developed at the site.[1] An initial grant of £37,500 was awarded to the project in March, 2009 by the Heritage Lottery Fund,[1] and was used to commission Davies Sutton Architects[20] to drawn up architectural plans for the renovation.[21] The "Galilee Project" website was launched the following September, with information about the chapel, its history, and the proposed renovations.[22] The project was also presented to the Llantwit Major community during the St. Illtud's Day Festival Weekend on 7 November 2009, with presentations by Davies Sutton Architects, games, and contests.[23] In December 2010, the project was awarded a nearly £300,000 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund for the purpose of refurbishing the chapel.[1][24]

Throughout 2011, the project focused on raising additional funds and also held a series of lectures on the history of the site.[25] In April, 2012, sufficient funding was secured to begin building on the project, and work was begun the following September. Archeological excavations were conducted simultaneously with renovations, and in November they were surprised to find 8 complete skeletons in and around the chapel.[26] As the chapel was being renovated, the Celtic stones were cleaned and prepared for their move to their new home in the chapel. In October, they made the short journey from the West Chapel to Galilee exhibition space.[27]

After 400 years of ruin, the restored chapel was opened on 2 November 2013.[28] The West Church was packed with visitors awaiting the moment when the doors would be opened to the Galilee Chapel. The opening ceremony was marked by a speech and prayer from the Reverend Huw Butler, and the red ribbon was cut by Llantwit's oldest resident, 94-year-old Gladys Kilby, in the presence of the youngest member of the community, Violet, just one day old![28][29] And art and music festival was also held, and the following day the chapel was rededicated at a service presided over by Dr. Barry Morgan, Archbishop of Wales; Phillip Morris, Archdeacon of Margam; Huw Butler, Rector of Llantwit Major; and John Webber, former Rector of Llantwit Major. A sermon was preached by Phillip Morris, and that evening a Songs of Praise service was held,[30] featuring the soloist Charlotte Ellet from the Welsh National Opera.[19]

The total cost of the project was nearly £850,000,.[19][29] Contributions came from the Heritage Lottery Fund,[1] The Vale of Glamorgan Council which awarded the project £70,000 from the ‘Pride in Our Heritage’ Grant,[31] church fundraising, and a number of individual private donors, the "Friends of St. Illtud's.[32] Notable supported include the Rt Revd Dr Barry Morgan Archbishop of Wales; the Most Revd Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, Professor John Davies author and Welsh historian; Jane Hutt and Andrew R. T. Davies, Welsh AMs; The current and former Lord Lieutenants of South Glamorgan, Dr Peter Beck and Captain Sir Norman Lloyd-Edwards; The Mayor of Llantwit Major; The Mayor of the Vale of Glamorgan; the Abbots of Belmont and Downside Abbey; Dr. Madeline Grey, Senior Lecturer in History, University of South Wales; Dr David Petts, Dept of Archaeology, Durham; and Dr Jonathan Wooding, Director, Centre for the Study of religion in Celtic Societies, Lampeter.

Renovations

Because the chapel was in ruins for nearly 400 years of its life, the architectural team responsible for its renovation felt that this "ruined" state formed a significant portion of its life, and should not be ignored in the proposed renovations.[21] The renovations were designed to retain the character of a ruin in the finished building, by retaining all existing walls and architectural details, and constructing new features in such a way that they touched the existing structure "very lightly."[21] Further, all new work was designed to be totally reversible, and not historic fabric was damaged in the process of developing the project.[21] The redesign also made the site wheelchair accessible, with a permanent wooden ramp covering the steps to the entrance, and a disabled toilet located within the chapel.[21]

The new roof is supported by a central timber frame, and second mezzanine floor was constructed housing offices.[21] The mezzanine floor does not completely fill the space, but stop short of the west gable to a loft display space for the Celtic stones. On the lower floor, a space was constructed to display the Celtic stones and modern bathroom were installed, and the former sacristy building was fitted with a tea making station.[21] The upper floor of the sacristy serves as an archive and research space.

The display space for the stones is fitted with simple, striking materials – the floor is polished limestone, and the walls are a simple limewashed white, providing a minimalist background to contrast with the rugged grey Celtic stones.[21]

The renovation of the site employed a number of local contractors and artisans, including Corinthian Stone Masonry,[33] which was responsible for working with the existing stone walls; Veon Glass designed and produced the many frameless glass windows and doors within the chapel, including the innovative windows fitted into the crumbling walls of the chapel.[34]

The Celtic Stones

One of the purposes of the renovation was to make a new home for the parish's ancient Celtic stones. These stones date from the 9th and 10th centuries, and had previously been housed in the West church. They had previously been located within the main church, some in the churchyard, and some even in private gardens in the town. They were brought into the church for protection during the renovations of the late 19th century.[35][36]

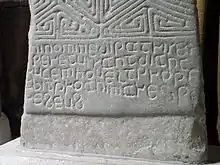

The Houelt Cross is a striking example of a Celtic wheel cross. It features beautiful interlacing carvings, and commemorates the father of Houelt ap Rhys (Hywel ap Rhys), ruler of Glywysing (Glamorgan) in the 9th century.[36] There have been a number of readings of the Latin inscription, e.g. R. A. Stewart Macalister read it as "NINOMINEDIPATRISE/TS | PERETUSSANTDIANC | --]UCEMHOUELTPROPE | --]BITPROANIMARESPA | --]ESEUS" but fewer translations. In 1950 Victor Erle Nash-Williams translated it as "In the Name of God the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. This cross Houelt (PN) prepared for the soul of Res (PN) his father" while in 1976 the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales translated it as "In the name of God, the Father and the Holy Spirit, Houelt (PN) prepared this cross for the soul of Res (PN) his father".[37]

The Sampson Cross is 2.15 meters high, and was probably once capped by a wheel cross, which is now missing. It is inscribed on the west and east faces. The West inscription reads: +SAMSON POSUIT HANC CRUCEM + PRO ANIMA EIUS +, or, "Samson placed his cross for his soul." The east face reads: + ILTUTI SAMSON REGIS SAMUEL + EBISAR +, or, "(For the soul of) Illtud, Samson the King, Samuel Ebisar."[36][38] This cross originally lay in the churchyard near the path on the north side of the church. When it was raised to bring it indoors, two skeletons were found beneath it.[38]

The Sampson Pillar, sometimes known as the "King's Stone,"[19] is 2.75 meters high and badly eroded, but once bore an inscription bearing the name of Sampson the Abbot (identity unknown), Artmail (another abbot) and Ithel, a 9th-century king of Gwent.[36] Its inscription reads: IN NOMINE DI SUMMI INCIPIT CRUX SALVATORIS QUAE PREPARAVIT SAMSONI ABATI PRO ANIMA SUA ET PRO ANIMA *IUTHAHELO REX ET ARTMAIL ET TECAN, or "In the name of the most high God begins the cross of the Saviour which Samson the Abbot prepared for his soul, and for the soul of Iuthahelo the King and of Artmail and of Tecan." Iuthahelo is thought to be Ithel, a king of Gwent who died in 846.[38]

This stone has a curious legendary story attached to it, in that while it made its home in the churchyard, a giant's grave was dug next to the stone. The "giant" was a 7 ft, 7in youth known as "Will the Giant."[19] The stone fell into the grave, nearly killing some mourners, and when it was deemed too heavy to remove, it was buried in the grave with the giant. The stone was rediscovered by Iolo Morganwg in 1789, when it was excavated and removed from the grave.[19]

The stones were restored by stone conservator Corinne Evans, who used a combination of steam cleaning and chemical poultices to remove over 1000 years worth of marks left by time, weather, and human impact.[35] Some areas of the stone had deposits of "fine paint splashes" that required scalpel work to be removed.[35]

Phase II

As the Galilee Project neared completion and the Celtic stones were moved to their new home in the Galilee Chapel, a "Phase II" project was proposed for the improvement and renovation of the newly cleared West chapel.[39] Proposed improvements include new flooring, heating, lighting, and storage facilities. The proposed refurbishment would make the West chapel more accessible to the Llantwit Major community, and provide a space for meetings, workshops, performances, and exhibitions.[40]

Baptismal font

Baptismal font Interior of the church

Interior of the church Wall painting of St.Christopher thought to have been painted about 1400

Wall painting of St.Christopher thought to have been painted about 1400 Interior of the East chapel

Interior of the East chapel Effigy

Effigy

See also

- Margam Stones Museum (Celtic stones found in Port Talbot area)

- St Teilo Church, Merthyr Mawr, Bridgend (collection of carved stones in the churchyard)

References

- "Christmas comes early for 'Westminster Abbey of Wales' thanks to HLF funding". Heritage Lottery Fund. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- "St Illtud's Church". The Galilee Project. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Theodosius I. "Banning of Other Religions Theodosian Code XVI.i.2". Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Griffin, Justin E. (30 November 2012). Glastonbury and the Grail: Did Joseph of Aramathea Bring the Sacred Relic to Britain?. page 94. ISBN 9780786492398. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Lewis, Samuel. "LaleA Topographical Dictionary of Walesston – Lawrenny". Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Fryer, Alfred C. "Llantwit Major, a Fifth Century University". Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "The Book of Llandaff". Chapter II. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Newell, Ebenezer Josiah (1887). A popular history of the ancient British church: with special reference to the church in Wales (Public domain ed.). Society for promoting Christian knowledge. pp. 115–. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Morganwg, Iolo. "Iolo manuscripts. A selection of ancient Welsh manuscripts, in prose and verse, from the collection made by the late Edward Williams, Iolo Morganwg, for the purpose of forming a continuation of the Myfyrian archaiology; and subsequently proposed as materials for a new history of Wales". Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- The art journal London (Public domain ed.). Virtue. 1860. pp. 217–. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Nelson, Lynn H. "The Establishment of the Marcher Lordships". The Normans in South Wales, 1070–1171. page 99. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Newell, Ebenezer Josiah. "A Popular History of the Ancient British Church, With Special Reference to the Church in Wales". Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Llantwit Major Historical Society. "St. Illtud's Church". Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Williams, Peter N. (March 2001). The Sacred Places of Wales: A Modern Pilgrimage. Wales Books. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-7596-0785-9. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- "The Galilee Project – The Galilee Chapel II". The Galilee Project. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Llanilltud: Britains earliest centre of learning, 2013, accessed 3 June 2015

- "The Galilee Project". Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "The Galilee Project – Opening Weekend Photo Montage". Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Galilee Chapel reopens in Llantwit Major as home for Celtic crosses". BBC News. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Galilee Chapel, St. Illtud's Church". Davies Sutton Architects. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "David Sutton Architects – Galilee Chapel Plans" (PDF). The Galilee Project. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "The Galilee Chapel Project – Project Launch". The Galilee Chapel Project. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Galilee Chapel Project – Community Launch". The Galilee Chapel Project. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Llantwit Major : Heritage Lottery grant provides funding boost for Galilee Chapel project". Welsh Conservatives. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "The Galilee Project – News". The Galilee Project. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "The Galilee Chapel – Skeletons Uncovered". The Galilee Chapel. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "The Galilee Chapel – Stones Make Their Move". The Galilee Chapel. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "The Galilee Chapel – Galilee Chapel Opens!". The Galilee Chapel. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "800-year-old chapel 'ruin' to reopen as visitor centre after £850k refurbishment". Wales Online. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "The Galilee Project – Rededication of the Galilee Chapel". The Galilee Project. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "Pride in our Heritage: St Illtuds Church and the Galilee Chapel, Llantwit Major". Vale of Glamorgan Council. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "The Galillee Project: Finances". The Galilee Project. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Corinthian Stone Masonry". Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Galilee Chapel, St Illtud's Church, Llantwit Major, South Wales". Veon Glass. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Llantwit Major: Celtic crosses' new St Illtud's church home". BBC News. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "The Galilee Project – The Celtic Crosses". The Galilee Project. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "CISP - LTWIT/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones. University College London. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "The Rectorial Benefice of Llantwit Major: Celtic Stones". Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Proposed Improvements to Llantwit Major Church". Vale Center for Voluntary Services. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- "St.Illtud's – West Church refurbishment" (PDF). Vale Center for Voluntary Services. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

External links

Media related to St Illtyd's Church, Llantwit Major at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to St Illtyd's Church, Llantwit Major at Wikimedia Commons- Llantwit Major Parish Church website

- St. Illtud's Galilee Chapel Project

- Llantwit Major: A Fifth Century University

- YouTube video of the Galilee Chapel Rebuild

- St. Illtyd's Church on Facebook

- The Life of St. Illtud

- Artwork at St Illtyd