Steven Shapin

Steven Shapin (born 1943) is an American historian and sociologist of science. He is the Franklin L. Ford Research Professor of the History of Science at Harvard University.[2] He is considered one of the earliest scholars on the sociology of scientific knowledge,[3] and is credited with creating new approaches.[4] He has won many awards, including the 2014 George Sarton Medal of the History of Science Society for career contributions to the field.[5]

Steven Shapin | |

|---|---|

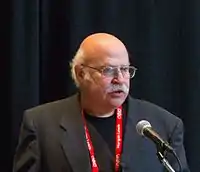

Shapin in 2008 | |

| Born | 1943 New York City, New York, U.S.[1] |

| Education | Reed College (B.A., 1966) University of Wisconsin (M.A., 1967) University of Pennsylvania (PhD, 1971) |

| Known for | Research on the history and sociology of science |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Harvard University |

Career

Shapin was trained as a biologist at Reed College and did graduate work in genetics at the University of Wisconsin before taking a Ph.D. in the History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania in 1971.[1]

From 1972 to 1989, he was Lecturer, then Reader, at the Science Studies Unit, Edinburgh University, and, from 1989 to 2003, Professor of Sociology at the University of California, San Diego, before taking up an appointment at the Department of the History of Science at Harvard. He has taught for brief periods at Columbia University, Tel-Aviv University,[1] and at the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo, Italy.[6] In 2012, he was the S. T. Lee Visiting Professorial Fellow, School of Advanced Study, University of London.[7]

He has written broadly on the history and sociology of science. Among his concerns are scientists, their ethical choices, and the basis of scientific credibility.[8] He revisioned the role of experiment by examining where experiments took place and who performed them. He is credited with restructuring the field's approach to “big issues” in science such as truth, trust, scientific identity, and moral authority.[4]

"The practice of science, both conceptually and instrumentally, is seen to be full of social assumptions. Crucial to their work is the idea that science is based on the public's faith in it. This is why it is important to keep explaining how sound knowledge is generated, how the process works, who takes part in the process and how."[9]

His books on 17th-century science include the "classic book"[10] Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (1985, with Simon Schaffer); his "path-breaking book" A Social History of Truth (1994),[11] The Scientific Revolution (1996, now translated into 18 languages), and, on modern entrepreneurial science, The Scientific Life (2008). A collection of his essays is Never Pure (2010).[2][12] His current research interests include the history of dietetics and the history and sociology of taste and subjective judgment, especially in relation to food and wine.[13]

He is a regular contributor to the London Review of Books[14] and he has written for Harper's Magazine[15] and The New Yorker.[16]

Awards

| External media | |

|---|---|

| |

| Audio | |

| Video | |

His honors include the John Desmond Bernal Prize (2001)[17] and the Ludwik Fleck Prize of the Society for Social Studies of Science (1996),[18] the Robert K. Merton Prize of the American Sociological Association,[19] the Herbert Dingle Prize of the British Society for the History of Science (1999),[20] a Guggenheim Fellowship (1979),[21] the Derek Price Prize of the History of Science Society, a Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, and, with Simon Schaffer, the Erasmus Prize (2005).[9] He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[22] In 2014, he received the George Sarton Medal of the History of Science Society for career contributions to the field.[4][5]

Bibliography

- With Barry Barnes (ed.), Natural order: historical studies of scientific culture, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1979.

- With Simon Schaffer, Leviathan and the air-pump : Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life ; including a translation of Thomas Hobbes, Dialogus physicus de natura aeris by Simon Schaffer, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1985; 1989; new edition, 2011

- A social history of truth: civility and science in seventeenth-century England, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.[11]

- The scientific revolution, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- With Christopher Lawrence (ed.), Science incarnate: historical embodiments of natural knowledge, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- The scientific life: a moral history of a late modern vocation, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008.[23]

- Never pure: historical studies of science as if it was produced by people with bodies, situated in time, space, culture, and society, and struggling for credibility and authority, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, 568 pages (ISBN 978-0801894213).

- "A Theorist of (Not Quite) Everything" (review of David Cahan, Helmholtz: A Life in Science, University of Chicago Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0-226-48114-2, 937 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 15 (10 October 2019), pp. 29–31.

References

- "Curriculum Vitae, Steven Shapin" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Steven Shapin Franklin L. Ford Research Professor of the History of Science". Harvard University. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Thompson, Charis (2005). Making Parents: the ontological choreography of reproductive technologies. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. p. 36. ISBN 9780262201568. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Reuell, Peter (November 18, 2014). "A lifetime of scholarship, recognized". Harvard Gazette.

- "Sarton Medal". History of Science Society. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Visiting Professors". Università degli Studi di Scienze Gastronomiche. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Harvard's Professor Steven Shapin to join London's School of Advanced Study as ST Lee Visiting Fellow". Universities News. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- "Society's Choices: Social and Ethical Decision Making in Biomedicine". National Academy of Sciences. 1995.

- "Former Laureates". Praemium Erasmianum Foundation. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Cohen, H. Floris (2010). How modern science came into the world. Four civilizations, one 17th-century breakthrough (Second ed.). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 506–508. ISBN 978-9089642394. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Rabinow, Paul; Dan-Cohen, Talia (2006). A machine to make a future : biotech chronicles (New ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 9780691126142.

- "Publications". Harvard University. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Keighren, Innes M. (2011). "Review of Shapin, Steven, 'Never Pure: Historical Studies of Science as if It Was Produced by People with Bodies, Situated in Time, Space, Culture, and Society, and Struggling for Credibility and Authority'". H-HistGeog, H-Net Reviews.

- "Steven Shapin". London Review of Books. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Steven Shapin". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Contributor Steven Shapin". The New Yorker. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "John Desmond Bernal Prize". Society for Social Studies of Science. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Ludwik Fleck Prize". Society for Social Studies of Science. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Steven Shapin". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Dingle Prize". British Society for the History of Science. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Steven Shapin". John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "The American Academy of Arts and Sciences". Reed College. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "An interview with Steven Shapin author of The Scientific Life: A Moral History of a Late Modern Vocation". University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Steven Shapin |

| Library resources about Steven Shapin |

| By Steven Shapin |

|---|

- Faculty home page

- Curriculum Vitae of Steven Shapin

- Works by or about Steven Shapin in libraries (WorldCat catalog)