Strange Brother

Strange Brother is a gay novel written by Blair Niles published in 1931. The story is about a platonic relationship between a heterosexual woman and a gay man and takes place in New York City in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

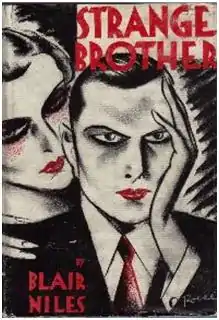

First edition cover | |

| Author | Blair Niles |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Horace Liveright, New York |

Publication date | 1931 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 341 pp |

Strange Brother provides an early and objective documentation of homosexual issues during the Harlem Renaissance.[1]

Plot summary

Mark Thornton, the story's protagonist, moves to New York City in hopes of feeling like less of an outsider. At a nightclub in Harlem he meets and befriends June Westbrook. One night they witness a man named Nelly being arrested. June encourages Mark to investigate. This leads Mark to attend Nelly's trial, where he is found guilty and sentenced to six months' imprisonment on Welfare Island for his feminine affections and gestures. Next Mark researches the crimes against nature sections of the penal code. Shaken up by his findings and the events, Mark confesses his own homosexuality to June.

Mark and June's friendship continues to grow, and June introduces Mark to a number of friends in her social circle. Various social interactions ensue including a dinner party for a departing professor, a trip to a nightspot featuring a singer called Glory who sings Creole Love Call and attending a drag ball. Despite reading Walt Whitman's poetry collection Leaves of Grass, Edward Carpenter's series of papers Love's Coming of Age, and Countee Cullen's poetry, Mark is afraid to come out. Subsequently, Mark is threatened with being outed at work.[2] In response to this threat, Mark commits suicide by shooting himself.[3]

Characters

Tom Burden: An older gay man and platonic friend who urges Mark to develop his drawing talents. Tom leads Mark to realize his homosexuality before he himself travels abroad.

Philip Crane (Phil): A handsome, muscular and heterosexual man who studies tropical entomology. Phil is Jane's cousin and companion on whom Mark has a secret crush.

Palmer Fleming: June's ex-husband whom she witnesses dancing with a scantily clad young man at a Drag Ball.

Harold Grant (Nelly) : A 21-year-old, outwardly effeminate African American man and drag queen whose arrest concerns June and Mark.

Irwin Hesse: A professor who is a Jewish man from continental Europe. Dr. Hesse experiments with sex differences in animals, focusing on the endocrine system, polymorphism, and gynandromorphism. Dr. Hesse asserts that sex differences are chemical and "abnormals" make up 2-3% of the general population.

Lilly-Marie: A friend of Mark's who is a gay ex-convict.

Peggy: A young woman who has a romantic interest in Mark, but marries Phil.

Quinn: An older Irish man who is the janitor at Mark's settlement house.

Rico: A Sicilian boy and fruit vendor whose stand is outside Mark's settlement house.

Evan Rysdale: An artist whom June befriends while summering at Ogunquit, Maine.

Glory: A Harlem nightclub singer.

Mark Thornton: The protagonist of the story, Mark is a 22-year-old Midwestern man who has traveled to New York City. He is not outwardly effeminate and teaches drawing at a local settlement house.

Seth Vaughn: A young man and distinguished author and lecturer who does not return June Westbrook's affections.

June Westbrook: June is a young heterosexual divorcée who works as a newspaper columnist. She is a central character in the story, being Mark's closest friend.

It has been suggested that the Harlem nightclub entertainer in the novel named Glory is based upon the jazz singer Adelaide Hall who introduced the song “Creole Love Call” in 1927, but this is probably unlikely as Adelaide Hall and Beatrice Lillie are the only contemporary entertainers of the time mentioned in the text. This happens when Hall and Lillie are rumoured to be at the Drag Ball.[4]

Publication history

Strange Brother has been reprinted a number of times since its initial 1931 Liveright publication in New York, as follows:

- Thomas Werner Laurie, 1931 (British publication)

- Harris Publishing Company, 1949

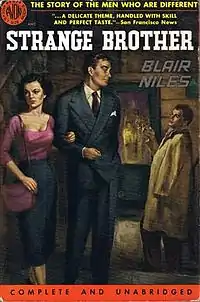

- Avon Books, 1952

- Arno Press, 1975

- Gay Men's Press, 1991

- Ayer Company Publishers, 2002

Literary significance and criticism

Strange Brother received mixed reviews upon its publication. Reviewers were not offended by the homosexual theme and noted the situations in the novel were portrayed with tolerance and sympathy rather than approval. The novel was praised for being interesting and informative, but did not receive praise for its execution as an engaging novel that comes to life.

Critical commentary

Henry Gerber, a gay critic wrote in 1934, "[Strange Brother is] an ideal anti-homosexual propaganda." Ian Young numbers it among a group of early gay novels that is "cast in the form of a tragic melodrama."[3] George-Michel Sarotte notes the sympathetic nature of the book, but also points out that it "is more of a psychosociological investigation than a novel." He goes on to credit Blair Niles for being one of the first authors to portray a continuum of sexuality, and for promoting tolerance and compassion."[5] According to editor and author Anthony Slide, Strange Brother illustrates the "basic assumption that gay characters in literature must come to a tragic end."[6]

Journalistic focus

The book has been praised for its journalistic focus. Ben Duncan's perspective was published in the January 25, 1979 issue of the Gay News newspaper, "The book remains and is welcome now, as a monument of good reporting."[7] Susan Stryker, a scholar, notes that "[Blair Niles] treats Manhattan's homosexual subculture much the same way she does any other exotic locale."[1] Again, Slide notes that Niles' anthropological approach to documenting homosexuality as well as the Harlem Negro in Strange Brother "is fascinating to a modern readership."[8] George-Michel Sarotte calls the work a thorough study of a variety of homosexuals, showcasing both whites and blacks, and a range of homosexual life styles from transvestite to the "well-adjusted male". The homosexual's legal, and societal relationships both in large cities and small towns are covered. Additionally the psychological history from childhood to adulthood is canvassed, including commitments, identifying with homosexual literature, guilt, solitude, sadness, blackmail and suicide.[5]

References

- Notes

- Stryker, Susan (2001). Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. pp. 97, 100.

- Austen, Roger, Playing the Game: The Homosexual Novel in America, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1977, pp 65

- Young, Ian (1975). The Male Homosexual in Literature: A Bibliography. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press. p. 153.

- Lost Gay Novels: A Reference Guide to Fifty Works from the First Half of the Century by Anthony Slide – Chapter 36, Strange Brother: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=So8EIVtTFyYC&pg=PT190&lpg=PT190&dq=blair+niles+adelaide+hall&source=bl&ots=ReZehv9gUJ&sig=Xy_744hnN9_S-ko7BdTDHD9S0Ds&hl=en&sa=X&ei=mPGuVIeFJo7U7AaUmICoBQ&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=blair%20niles%20adelaide%20hall&f=false

- Sarotte, Georges-Michel (1978). Like a Brother: Male Homosexuality in the American Novel and Theatre from Herman Melville to James Baldwin. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press. p. 18.

- Slide, Anthony (1977). Lost Gay Novels: A Reference Guide to Fifty Works from the First Half of the Twentieth Century. Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press. p. 1.

- Slide (1977). Lost Gay Novels. p. 140.

- Slide (1977). Lost Gay Novels. p. 137.

- Bibliography

- Austen, Roger (1977). Playing the Game: The Homosexual Novel in America (1st ed.). Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company. ISBN 978-0-672-52287-1.

- Niles, Blair (1952). Strange Brother (reprint ed.). New York, NY: Avon Books.

- Niles, Blair (1991). Strange Brother (Gay Modern Classics reprint ed.). London: Gay Men's Press Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85449-167-4.

- Sarotte, Georges-Michel (1978). Like a Brother, Like a Lover: Male Homosexuality in the American Novel and Theatre from Herman Melville to James Baldwin (1st English ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-12765-3.

- Boone, Joseph Allen (1998). Libidinal Currents: Sexuality and the Shaping of Modernism (1st ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06466-6.

- Slide, Anthony (2003). Lost Gay Novels: A Reference Guide to Fifty Works from the First Half of the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press. ISBN 978-1-56023-413-5.

- Stryker, Susan (2001). Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback (1st ed.). San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-3020-1.

- Walker, Lisa (2001). Looking Like What You Are: Sexual Style, Race, and Lesbian Identity (1st ed.). New York, NY: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9371-8.

- Young, Ian (1975). The Male Homosexual in Literature: A Bibliography (1st ed.). Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-0861-4.