Suvarnabhumi

Suvarṇabhūmi (Sanskrit: सुवर्णभूमि; Pali: Suvaṇṇabhūmi)[lower-alpha 1] is a toponym, that appears in many ancient Indian literary sources and Buddhist texts[1] such as the Mahavamsa,[2] some stories of the Jataka tales,[3][4] the Milinda Panha[5] and the Ramayana.[6]

There is a common misunderstanding that the Edicts of Ashoka mention this name. The truth is the edicts relate only the kings' names and never reference Suvarnabhumi in the text. Moreover, all of the kings referenced in the text reigned their cities in the region that located beyond the Sindhu to the west. The misunderstanding might come from a mixing of the story of Ashoka sending his Buddhist missionaries to Suvarnabhumi in "Mahavamsa" and his edicts.

Though its exact location is unknown and remains a matter of debate, Suvarṇabhūmi was an important port along trade routes that run through the Indian Ocean, setting sail from the wealthy ports in Basra, Ubullah and Siraf, through Muscat, Malabar, Ceylon. Nicobars, Kedah and on through the Strait of Malacca to fabled Suvarṇabhūmi.[7]

Historiography

Suvaṇṇabhumī means "Golden Land" or "Land of Gold" and the ancient sources have associated it with one of a variety of places throughout the Southeast Asian region.

It might also be the source of the Western concept of Aurea Regio in Claudius Ptolemy's Trans-Gangetic India or India beyond the Ganges and the Golden Chersonese of the Greek and Roman geographers and sailors.[8] The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea refers to the Land of Gold, Chryse, and describes it as "an island in the ocean, the furthest extremity towards the east of the inhabited world, lying under the rising sun itself, called Chryse... Beyond this country... there lies a very great inland city called Thina".[9] Dionysius Periegetes mentioned: "The island of Chryse (Gold), situated at the very rising of the Sun".[10]

Or, as Priscian put it in his popular rendition of Periegetes: “if your ship… takes you to where the rising sun returns its warm light, then will be seen the Isle of Gold with its fertile soil.”[11] Avienus referred to the Insula Aurea (Golden Isle) located where "the Scythian seas give rise to the Dawn".[12] Josephus speaks of the "Aurea Chersonesus", which he equates with the Biblical Ophir, whence the ships of Tyre and Israel brought back gold for the Temple of Jerusalem.[13] The city of Thina was described by Ptolemy's Geography as the capital city of the country on the eastern shores of the Magnus Sinus (Gulf of Thailand).

Location

The location of Suvarnabhumi has been the subject of much debate, both in scholarly and nationalistic agendas. It remains one of the most mythified and contentious toponyms in the history of Asia.[14] Scholars have identified two regions as possible locations for the ancient Suvarnabhumi: Insular Southeast Asia or Southern India.[15] In a study of the various literary sources for the location of Suvannabhumi, Saw Mra Aung concluded that it was impossible to draw a decisive conclusion on this, and that only thorough scientific research would reveal which of several versions of Suvannabhumi was the original.[16]

Some have speculated that this country refers to the Kingdom of Funan. The main port of Funan was Cattigara Sinarum statio (Kattigara the port of the Sinae).[17]

Due to many factors, including the lack of historical evidence, the absence of scholarly consensus, various cultures in Southeast Asia identify Suwannaphum as an ancient kingdom there and claim ethnic and political descendancy as its successors.[18] As no such claim or legend existed prior to the translation and publication of the Edicts, scholars see these claims as based in nationalism or attempts to claim the title of first Buddhists in South-East Asia.[14]

Cambodia theory

Funan (1st–7th century) was the first kingdom in Cambodian history and it was also the first Indianized kingdom prospered in Southeast Asia. Both Hinduism and Buddhism flourished in this kingdom. According to the Chinese records, two Buddhist monks from Funan, named Mandrasena and Sanghapala, took up residency in China in the 5th to 6th centuries, and translated several Buddhist sūtras from Sanskrit (or a prakrit) into Chinese.[19]

The oldest archaeological evidence of Indianized civilization in Southeast Asia comes from central Burma, central and southern Thailand, and the lower Mekong delta. These finds belong to the period of Funan Kingdom or Nokor Phnom, present day Cambodia and South Vietnam including part of Burma, Lao, and Thailand, which was the first political centre established in Southeast Asia. Taking into account the epigraphic and archaeological evidence, the Suvarnabhumi mentioned in the early texts must be identified with these areas.[20] Of these areas, only Funan had maritime links with India through its port at Oc Eo. Therefore although Suvarnabhumi in time became a generic name broadly applied to all the lands east of India, particularly Sumatra, its earliest application was probably to Funan. Furthermore, the Chinese name "Funan" for Cambodia, may be a transcription of the "Suvaṇṇa" of "Suvaṇṇabhumī".

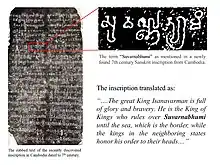

In December 2017, Dr Vong Sotheara, of the Royal University of Phnom Penh, discovered a Pre-Angkorian stone inscription in the Province of Kampong Speu, Basedth District, which he tentatively dated to 633 AD. According to him, the inscription would “prove that Suvarnabhumi was the Khmer Empire.” The inscription was issued during the reign of King Isanavarman I (616–637 AD) of the Cambodian Kingdom of Chenla, the successor of Funan and the predecessor of Khmer Empire. The inscription, translated, read:

“The great King Isanavarman is full of glory and bravery. He is the King of Kings, who rules over Suvarnabhumi until the sea, which is the border, while the kings in the neighbouring states honour his order to their heads”.

The Inscription is the oldest evidence ever found in Southeast Asia, mentioning Suvarnabhumi and identified it with Chenla. The inscription is now exhibits in the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh. However, his claim and the findings are yet to be peer-reviewed, and they are remained in doubt with other historians and archaeology experts across the region. [21]

Thailand theory

In Thailand, government proclamations and national museums insist that Suwannaphum was somewhere in the coast of central plain, especially at the ancient city of U Thong, which might be the origin of the Mon Dvaravati Culture.[22] These claims are not based on any historical records but on archaeological evidences of human settlements in the area dating back more than 4,000 years and the findings of 3rd century Roman coins.[23] The Thai government named the new Bangkok airport, Suvarnabhumi Airport, after the mythic kingdom of Suwannaphum, in celebration of this tradition. This tradition, however, is doubted by scholars for the same reason as the Burman claim. The migration of the Thai peoples into Southeast Asia did not occur until centuries later, long after the Pyu, Malays, Mons and Khmers had established their respective kingdoms.[24] Suphan Buri (from the Sanskrit, Suvarnapura, "Golden City") in present day west/central Thailand, was founded in 877-882 as a city of the Mon-Khmer kingdom of Dvaravati with the name, Meuang Thawarawadi Si Suphannaphumi ("the Dvaravati city of Suvarnabhumi"), indicating that Dvaravati at that time identified as Suvarnabhumi.[25]

Insular Southeast Asia theory

.tif.jpg.webp)

The strongest and earliest clue referring to the Malay Peninsula came from Claudius Ptolemy's Geography Geography (Ptolemy) who referred to it as Chersonesus Aurea (which literally means Golden Peninsula) which pinpointed exactly that location in South East Asia.[26]

The term Suvarnabhumi ("Land of Gold"), is commonly thought to refer to the Southeast Asian Peninsula, including lower Burma and the Malay Peninsula. However there is another gold-referring term Suvarnadvipa (the Golden Island or Peninsula, where dvipa may refer to either a peninsula or an island),[27] which may correspond to the Indonesian Archipelago, especially Sumatra.[28] Both terms might refer to a powerful coastal or island kingdom in present-day Indonesia and Malaysia, possibly centered on Sumatra or Java. This corresponds to the gold production areas traditionally known in Minangkabau highlands in Barisan Mountains, Sumatra, and interior Borneo.[28] An eighth century Indian text known as the "Samaraiccakaha" describes a sea voyage to Suvarnadvipa and the making of bricks from the gold rich sands which they inscribed with the name dharana and then baked.[29] These pointing out to the direction of western part of insular Southeast Asia, especially Sumatra, Malay Peninsula, Borneo and Java.

Benefitting from its strategic location on the narrow Strait of Malacca, the insular theory argued that other than actually producing gold, it might also be based on such a kingdom's potential for power and wealth (hence, "Land of Gold") as a hub for sea-trade also known from vague descriptions of contemporary Chinese pilgrims to India. The kingdom referred to as the center of maritime trade between China and India was Srivijaya. Due to the Chinese writing system, however, the interpretations of Chinese historical sources are based on supposed correspondences of ideograms – and their possible phonetic equivalents – with known toponyms in the ancient Southeast Asian civilizations. Hendrik Kern concluded that Sumatra was the Suvarnadvipa mentioned in ancient Hindu texts and the island of Chryse mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and by Rufius Festus Avienus.[30]

The interpretation of early travel records is not always easy. The Javanese embassies to China in 860 and 873 CE refer to Java as rich in gold, although it was in fact devoid of any deposits. The Javanese would have had to import gold possibly from neighbouring Sumatra, Malay Peninsula or Borneo, where gold was still being mined in the 19th century and where ancient mining sites were located.[31] Even though Java did not have its own gold deposits, the texts make frequent references to the existence of goldsmiths, and it is clear from the archaeological evidence such as Wonoboyo Hoard, that this culture had developed a sophisticated gold working technology, which relied on the import of substantial quantities of the metal.[32]

The Padang Roco Inscription of 1286 CE, states that an image of Buddha Amoghapasa Lokeshvara was brought to Dharmasraya on the Upper Batang Hari - the river of Jambi - was transported from Bhumi Java (Java) to Suvarnabhumi (Sumatra), and erected by order of the Javanese ruler Kertanegara: the inscription clearly identifies Sumatra as Suvarnabhumi.[33]

There is actually new evidence that gold was more abundant in the Philippines than in Sumatra. Spanish chroniclers, when they stepped foot on Butuan, remarked that gold was so abundant that even houses were decorated with gold; "Pieces of gold, the size of walnuts and eggs are found by sifting the earth in the island of that king who came to our ships. All the dishes of that king are of gold and also some portion of his house as we were told by that king himself...He had a covering of silk on his head, and wore two large golden earrings fastened in his ears...At his side hung a dagger, the haft of which was somewhat long and all of gold, and its scabbard of carved wood. He had three spots of gold on every tooth, and his teeth appeared as if bound with gold." As written by Antonio Pigafetta on Rajah Siagu of Butuan during Magellan's voyage. Rajah Siagu was also a cousin of Rajah Humabon of the Rajahnate of Cebu, thus suggesting that the two Indianized kingdoms were in an alliance together with Hindu Kutai against the Islamic Sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu.

Butuan was so rich in treasures that a museum curator, Florina H. Capistrano-Baker, stated that it was even richer than the more well-known western maritime kingdom of Srivijaya; "The astonishing quantities and impressive quality of gold treasures recovered in Butuan suggest that its flourishing port settlement played an until recently little-recognized role in early Southeast Asian trade. Surprisingly, the amount of gold discovered in Butuan far exceeds that found in Sumatra, where the much better known flourishing kingdom of Srivijaya is said to have been located." This despite that most of the gold of Butuan were already looted by invaders.[34]

Bengal theory

A popular interpretation of Rabindranath Tagore's poem Amar Shonar Bangla serves as the basis for the claim that Suvarnabhumi was actually situated in central Bengal.[35] In some Jain texts, it is mentioned that merchants of Anga (in present-day Bihar, a state of India that borders with Bengal) regularly sailed to Suvarnabhumi, and ancient Bengal was in fact situated very close to Anga, connected by rivers of the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta. Bengal has also been described in ancient Indian and Southeast Asian chronicles as a "seafaring country", enjoying trade relations with Dravidian kingdoms, Sri Lanka, Java and Sumatra. Sinhalese tradition holds that the first king of Sri Lanka, Vijaya Singha, came from Bengal.[36] Moreover the region is commonly associated with gold - the soil of Bengal is known for its golden color (gangetic alluvial), golden harvest (rice), golden fruits (mangoes), golden minerals (gold and clay) and yellow skinned people. Bengal is described in ancient Sanskrit texts as 'Gaud-Desh' (Golden/Radiant land). During the reign of the Bengal Sultans and the Mughal Empire, central Bengal was home to a prosperous trading town called "Sonargaon" (Golden village), which was connected to North India by the Grand Trunk Road and was frequented by Arab, Persian and Chinese travelers, including Ibn Battuta and Zheng He. Even today, Bengalis often refer to their land as 'Shonar Bangla' (Golden Bengal), and the national anthem of Bangladesh - Amar Shonar Bangla (My Bengal of Gold), from the omonym Tagore's poem - is a reference to this theory.[37]

European Age of Discovery

The thirst for gold formed the most powerful incentive to explorers at the beginning of modern times; but although more and more extensive regions were brought to light by them, they sought in vain in the East Indian Archipelago for the Gold and Silver Islands where, according to the legends, the precious metals were to be gathered from the ground and did not need to be laboriously extracted from the interior of the earth. In spite of their failure, they found it difficult to give up the alluring picture. When they did not find what they sought in the regions which were indicated by the old legends and by the maps based thereon, they hoped for better success in still unexplored regions, and clutched with avidity at every hint that they were here to attain their object.[38]

The history of geography thus shows us how the Gold and Silver Islands were constantly, so to speak, wandering towards the East. Marco Polo spoke, in the most exaggerated language, of the wealth of gold in Zipangu, situated at the extremity of this part of the world, and had thus pointed out where the precious metals should preferably be sought. Martin Behaim, on his globe of 1492, revived the Argyre and Chryse of antiquity in these regions.[38]

In 1519, Cristóvão de Mendonça, was given instructions to search for the legendary Isles of Gold, said to lie to "beyond Sumatra", which he was unable to do, and in 1587 an expedition under the command of Pedro de Unamunu was sent to find them in the vicinity of Zipangu (Japan).[39] According to Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, in 1528 Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón in the ship Florida on a voyage from the Moluccas to Mexico reached a large island which he took for the Isla del Oro. This island has not been identified although it seems likely that it is Biak, Manus or one of the Schouten Islands on the north coast of New Guinea.[40]

Notes

References

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. ISBN 9788122411980. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- "To Suvarnabhumi he [Moggaliputta] sent Sona and Uttara"; Mahānāma, The Mahāvaṃsa, or, The Great Chronicle of Ceylon, translated into English by Wilhelm Geiger, assisted by Mabel Haynes Bode, with an addendum by G.C. Mendis, London, Luzac & Co. for the Pali Text Society, 1964, Chapter XII, "The Converting of Different Countries", p.86.

- Sussondi-Jātaka, Sankha-Jātaka, Mahājanaka-Jātaka, in Edward B. Cowell (ed.), The Jātaka: or Stories of the Buddha's Former Births, London, Cambridge University Press, 1897; reprinted Pali Text Society, dist. by Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969, Vol. III, p.124; Vol. IV, p.10; Vol. VI, p.22

- J. S. Speyer, The Jatakamala or Garland of Birth-Stories of Aryasura, Sacred Books of the Buddhists, Vol. I, London, Henry Frowde, 1895; reprint: Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1982, No.XIV, Supâragajâtaka, pp.453-462.

- R.K. Dube, "Southeast Asia as the Indian El-Dorado", in Chattopadhyaya, D. P. and Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy, and Culture (eds.), History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1999, Vol.1, Pt.3, C.G. Pande (ed.), India's Interaction with Southeast Asia, Chapter 6, pp.87-109.

- Anna T. N. Bennett. "Gold in early Southeast Asia, pargraph No 6". Open Edition. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of Tang Exotics. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

- Paul Wheatley (March 1, 2011). "Presidential Address: India Beyond the Ganges—Desultory Reflections on the Origins of Civilization in Southeast Asia". cambridge org. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- Lionel Casson (ed.), Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Princeton University Press, 1989, p.91.

- Dionysios Oecumenis Periegetes (Orbis Descriptio), lines 589-90; Dionysii Orbis Terrae Descriptio

- ”At navem pelago flectenti Aquilonis ab oris / Ad solem calido referentem lumen ab ortu, / Aurea spectetur tibi pinguibus insula glebis”; Priscianus Caesariensis, Periegesis Prisciani (lines 593-594), in Habes candide lector in hoc opere Prisciani volumen maius, Venetiis, Boneto Locatello, 1496, p.281.

- Rufius Festus Avienus, Descriptio orbis terrae, III, v.750-779. Descriptio orbis terrae

- "Solomon gave this command: That they should go along with his own stewards to the land that was of old called Ophir, but now the Aurea Chersonesus, which belongs to India, to fetch him gold."; Antiquities, 8:6:4.

- "Facts and Fiction: The Myth of Suvannabhumi Through the Thai and Burmese Looking Glass". Academia. July 1, 2018. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- R. C. Majumdar, Ancient Indian Colonies in the Far East, Vol. II, Suvarnadvipa, Calcutta, Modern Publishing Syndicate, 1937, Chapter IV, Suvarnadvipa, pp.37-47.Suvarnadvipa

- Saw Mra Aung, "The Accounts of Suvannabhumi from Various Literary Sources", Suvannabhumi: Multi-Disciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (Busan University of Foreign Studies, Korea), vol. 3, no.1, June 2011, pp.67-86.

- George Coedès, review of Paul Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese (Kuala Lumpur, 1961), in T'oung Pao 通報, vol.49, parts 4/5, 1962, pp.433-439; Claudius Ptolemy, Geography, Book I, chapter 17, paragraph 4; Louis Malleret, L’Archéologie du Delta du Mékong, Tome Troisiéme, La culture du Fu-nan, Paris, 1962, chap.XXV, "Oc-Èo et Kattigara", pp.421-54; "Mr. Caverhill seems very fairly to have proved that the ancient Cattagara [sic] is the same with the present Ponteamass [Banteaymeas], and the modern city Cambodia [Phnom Penh] the ancient metropolis of Sinae, or Thina", The Gentleman's Magazine, December 1768, "Epitome of Philosophical Transactions", vol.57, p.578; John Caverhill, "Some Attempts to ascertain the utmost Extent of the Knowledge of the Ancients in the East Indies", Philosophical Transactions, vol.57, 1767, pp.155-174.

- Prapod Assavavirulhakarn, The Ascendancy of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, Chieng Mai, Silkworm Books, 2010, p.55.

- T'oung Pao: International Journal of Chinese Studies. 1958. p. 185

- Pang Khat, «Le Bouddhisme au Cambodge», René de Berval, Présence du Bouddhisme, Paris, Gallimard, 1987, pp.535-551, pp.537, 538; Amarajiva Lochan, "India and Thailand: Early Trade Routes and Sea Ports", S.K. Maity, Upendra Thakur, A.K. Narain (eds,), Studies in Orientology: Essays in Memory of Prof. A.L. Basham, Agra, Y.K. Publishers, 1988, pp.222-235, pp.222, 229-230; Prapod Assavavirulhakarn, The Ascendancy of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, Chieng Mai, Silkworm Books, 2010, p.55; Promsak Jermsawatdi, Thai Art with Indian Influences, New Delhi, Abhinav Publications, 1979, chapter III, "Buddhist Art in Thailand", pp.16-24, p.17.

- Rinith Taing, “Was Cambodia home to Asia’s ancient ‘Land of Gold’?”, The Phnom Penh Post, 5 January, 2018.

- Damrong Rachanubhab, "History of Siam in the Period Antecedent to the Founding of Ayuddhya by King Phra Chao U Thong", Miscellaneous Articles: Written for the Journal of the Siam Society by His late Royal Highness Prince Damrong, Bangkok, 1962, pp.49-88, p.54; Promsak Jermsawatdi, Thai Art with Indian Influences, New Delhi, Abhinav Publications, 1979, pp.16-24. William J. Gedney, "A Possible Early Thai Route to the Sea", Journal of the Siam Society, Volume 76, 1988, pp.12-16.

- http://dasta.or.th/en/publicmedia/84-news/news-org

- The Siam Society: Miscellaneous Articles Written for the JSS by His Late Highness Prince Damrong. The Siam Society, Bangkok, B.E. 2505 (1962); Søren Ivarsson, Creating Laos: The Making of a Lao Space Between Indochina and Siam, 1860–1945, NIAS Press, 2008, pp.75-82.

- Manit Vallibhotama, "Muang U-Thong", Muang Boran Journal, Volume 14, no.1, January–March 1988, pp.29-44; Sisak Wanliphodom, Suwannaphum yu thi ni, Bangkok, 1998; Warunee Osatharom, Muang Suphan Through Changing Periods, Bangkok, Thammasat University Press, 2004; The Siam Society, Miscellaneous Articles Written for the JSS by His Late Highness Prince Damrong, The Siam Society, Bangkok, B.E. 2505 (1962); William J. Gedney, "A Possible Early Thai Route to the Sea", Journal of the Siam Society, Volume 76, 1988, pp.12-16.

- Gerini, G. E. (1909). "Researches on Ptolemy's geography of Eastern Asia (further India and Indo-Malay archipelago)". Asiatic Society Monographs. 1: 77–111.

- Paul Wheatley (1961). The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. pp. 177–184. OCLC 504030596.

- "Gold in early Southeast Asia". Archeosciences.

- Dube, 2003: 6

- H. Kern, "Java en het Goudeiland Volgens de Oudste Berichten", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, Volume 16, 1869, pp.638-648.; See also Gabriel Ferrand, "Suvarņadvīpa", in L'empire sumatranais de Crivijaya, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1922, p.121-134.

- Colless, 1975; Miksic, 1999: 19; Manning et al., 1980

- Wahyono Martowikrido, 1994; 1999

- Gabriel Ferrand, "Suvarņadvīpa", in L'empire sumatranais de Crivijaya, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1922, p.123-125; See also George Coedès, Les états hindouisés d'Indochine et d'Indonésie, Paris, De Boccard, 1948, p.337.

- "The Kingdom of Butuan". Philippine Gold: Treasures of Lost Kingdoms. Asia Society New York. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- Chung Tan (2015-03-18). Himalaya Calling. ISBN 9781938134609. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization...Ramayana refers to Yavadvipa. ISBN 9788122411980. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- Chung, Tan (2015-03-18). Himalaya Calling: The Origins of China and India. ISBN 9781938134616.

- E.W. Dahlgren, "Were the Hawaiian Islands visited by the Spaniards before their Discovery by Captain Cook in 1778?", Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar, Band 57. No.1, 1916–1917, pp.1-222, pp.47-48, 66.

- The Travels of Pedro Teixeira, tr. and annotated by W.F. Sinclair, London, Hakluyt Society, Series 2, Vol.9, 1902, p.10; H. R. Wagner and Pedro de Unamuno, "The Voyage of Pedro de Unamuno to California in 1587", California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Jul., 1923), pp. 140-160, p.142.

- “Alvaro de Saavedra….anduvieron 250 Leguas, hasta la isla del Oro, adonde tomaron Puerto, que es grande, y de Gente Negra, y con los cabellos crespos, y desnuda”; Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, Historia General de los Hechos de los Castellanos en las Islas i Tierra Firme del Mar Oceano, Madrid, 1601, Decada IV, libro III, cap.iv, p.60. June L. Whittaker, (ed.), Documents and Readings in New Guinea History: Pre-history to 1889, Milton, Jacaranda, 1975, pp,183-4.