Swedish Press

Swedish Press is a monthly magazine for Swedish-Americans and Swedish citizens living in the United States and Canada, as well as for North American businesses with links to Sweden. It is published 10 times a year (Feb, Mar, Apr, May, Jun/Jul, Aug, Sep, Oct, Nov, Dec/Jan). The magazine contains articles in both English and Swedish on subjects related to contemporary events in Sweden, as well as to Swedish associations in Canada and the United States. It covers all the latest Swedish trends, traditions, news and current affairs, along with exclusive features and interviews. Digital versions of the magazine may be found via the Swedish Press website, as well as on the online magazine newsstands Issuu[1] and Magzter[2]. The magazine is also present on Facebook and Instagram.

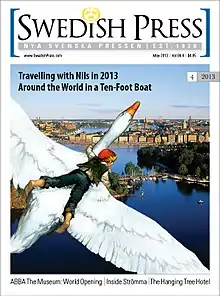

Swedish Press cover from May 2013 showing Nils Holgersson riding on a goose across Sweden. | |

| Editor-in-Chief | Claes Fredriksson |

|---|---|

| Categories | Magazine |

| Frequency | 10 issues annually |

| Format | 8.0" x 10¾" (203 x 273 mm) |

| Publisher | Claes Fredriksson |

| Founder | Helge Ekengren and Paul Johnson |

| Year founded | 24 January 1929 |

| Company | Swedish Press Inc. |

| Country | Canada |

| Based in | Vancouver BC |

| Language | English and Swedish |

| Website | www.swedishpress.com |

| ISSN | 0839-2323 |

History

Swedish Press started as a weekly broadsheet in 1929 in Vancouver when there were hundreds of Swedish newspapers in North America. Today, only the monthly Swedish Press and the bi-monthly Nordstjernan[3] tabloid in New York are left in all of North America. Swedish Press has subscribers in every US state and every Canadian province for its printed and electronic editions.

It was two Finno-Swedes, Helge Ekengren and Paul Johnson, who founded Svenska pressen. Ekengren provided space in the same building as his travel agency, and the first issue was dated 24 January 1929. The four-page weekly gave equal space for news from Sweden and Finland. When Ekengren left in 1933, Matt Lindfors became editor, assisted by Rud Månson who had already worked there for three years.

Financial difficulties dogged Svenska pressen, despite various appeals and refinancing schemes. In 1936 Lindfors sold the paper to Seattle’s Svenska posten, which printed his weekly Vancouver page. Less than a year later he took it back and changed the name to Nya svenska pressen (The New Swedish Press). In 1943 it was reorganized as a private company under the name Central Press Limited, having purchased its own printing equipment. A board of directors was elected and shares sold to cover capital expenses. At this time Lindfors was busy elsewhere and Einar Olson took over as editor for five years, followed by Rud Månson until Lindfors returned in 1961. Maj Brundin wrote articles under the pseudonym Röksignaler (Smoke Signals) and also served on the paper’s board of directors.

Lindfors was a tireless promoter of Sweden and things Swedish, especially among children. As Farbror Olle (Uncle Olle) he wrote a weekly column in Swedish, and in 1935 founded a club called Vårblomman (The Spring Flower). Members performed on his local CJOR radio program Echoes from Sweden just before Christmas, with prizes for those who signed up new members. The year before he had founded a young people’s club, Diamanten (The Diamond), also based on a weekly column, which by 1938 had 600 members. Farbror Olle organized the first of many summer camps at Swedish Park, which usually wound up with a public music program presented by Diamanten as well as races, vocal solos, and a public dance with live music. These activities were duly reported in Nya svenska pressen.

The paper faced another crisis in 1984 when the editors ─ professional journalist Jan Fränberg and his wife, Vicky ─ decided to return to Sweden. By this time the paper was publishing only ten issues a year. “The problem,“ lamented Jan, “was that the subscribers were dying of old age.” At this point Nya svenska pressen was one of the only five surviving Swedish newspapers in North America.

While it was true that original subscribers were dying, it was also true that most of their children and grandchildren could not read Swedish and did not identify strongly with Sweden. Immigration had virtually halted during the years from 1930 to 1950 because of the Depression, the Second World War, and reconstruction in Canada. When North America became a favored destination once again, many Swedish immigrants had already learned English at school as a compulsory subject. The loss of subscribers, coupled with escalating printing costs, sounded the death knell for hundreds of ethnic newspapers in North America.

Sture Wermee, who had worked as typographer and sometime editor since 1952, was determined that Nya svenska pressen should survive. Along with Swedish consul Ulf Waldén and others, he scouted around for an editor and found Anders and Hamida Neumüller. The couple agreed to try it for a year as a monthly, with the backing of the Swedish Press Society. They changed the name to Swedish Press/Nya svenska pressen, adopted a smart magazine format, and started producing the paper on a Macintosh computer. The Swedish Charitable Association, which raised money through bingo events, funded purchase of the new equipment, and the first issue appeared in January 1986. Continuing to contribute were journalist Ann-Charlotte Berglund, cartoonist Ernie Poignant, and Sven Seaholm, the paper’s poet laureate. New contributors included Mats Thölin with sports, Adele Heilborn with news from Sweden, and Roberta Larson with reports from the Swedish Canadian Rest Home.

Editor Anders Neumüller credited Canada’s multicultural policy and Vancouver’s Expo ’86 with generating enough advertising revenue to see Swedish Press through its critical first year. He also came close to meeting his goal of doubling the number of subscribers.

Since then, Swedish Press has become an international resource, keeping readers informed about events in Canada, Sweden, and the United States, very little of which is included in the mainstream media. The magazine also serves as a communication substitute for a national Swedish organization in Canada, something that has never existed in a meaningful way. Only a few of its thirty-two pages are in Swedish, and translations are available online. In 1994 Neumüller began publishing the quarterly Scandinavian Press [4] in a similar magazine format, but all in English. Associate editors provided copy from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, and Norway. Since then Anders and Hamida have sold both magazines and moved to Sweden. (History text adapted from Elinor Barr, “Swedes in Canada: Invisible Immigrants,” University Toronto Press 2015 with permission from the author.)

Recent activities

At the end of 2012, Claes and Joan Fredriksson purchased Swedish Press from Anders and Hamida Neumüller who retired and moved back to Sweden after a successful run of the magazine for 27 years. Claes and Joan revamped the magazine and are now producing a full-colour edition featuring the innovation and imagination that Sweden brings to the world. Readers are treated to stories on design, travel, music, fashion, and culture while enjoying a round-up of selected news. Other features include interviews with distinguished personalities and award-winning companies, along with stories on traditions and heritage.

Since late 2016, a new section has been introduced in the magazine called Swedish Press Connects, which aims to link the readers to a number of organizations with Swedish and North American roots. The organizations comprise SACC (Swedish American Chambers of Commerce)[5], SCA (Swedish Council of America)[6], SI (Swedish Institute)[7], Embassy of Sweden, Washington, D.C.[8], SWEA (Swedish Women's Educational Association)[9], and MIG Talks (Swedish Migration Agency)[10] so far, with more being added gradually. The articles provide regular updates on current events, educational opportunities, scholarships, and new or updated laws.

In 2016, Swedish Press received an award for "Excellence in Editorial Concept Art and Visual Presentation" from the National Ethnic Press and Media Council of Canada[11].

References

- https://swedishpress.com Official website

- https://books.google.ca/books?isbn=1442613742 Elinor Barr, “Swedes in Canada: Invisible Immigrants,” University Toronto Press 2015

Other sources

- Backlund, J. Oscar. “A Century of the Swedish American Press,” Swedish American Newspaper Company, Chicago, Illinois 1952

- Howard, Irene. “Vancouver’s Svenskar – A History of the Swedish Community in Vancouver,” Vancouver Historical Society 1970

External links

- https://issuu.com Issuu website

- https://magzter.com Archived 2017-07-25 at the Wayback Machine Magzter website

- http://nordstjernan.com Nordstjernan website

- http://scandpress.com Scandinavian Press website

- http://www.sacc-usa.org SACC website

- http://www.swedishcouncil.org SCA website

- https://eng.si.se SI website

- http://www.swedenabroad.com/en-GB/Embassies/Washington/ Embassy of Sweden (Washington DC) website

- https://www.swea.org SWEA website

- https://www.migrationsverket.se/English/About-the-Migration-Agency.html MIG website

- https://nepmcc.ca Official website of National Ethnic Press and Media Council of Canada