Syrian elephant

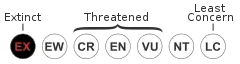

The Syrian elephant or Western Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus asurus) is a proposed name for the westernmost population of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), which became extinct in ancient times.[1] Skeletal remains of E. m. asurus have been recorded from the Middle East: Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria, from periods dating between at least 1800 BC and likely 700 BC.[3] Due to the lack of any Late Pleistocene or early to mid Holocene record for Asian elephants in the region, it has been suggested to have been anthropogenically introduced during the Bronze Age,[3] though this is disputed.[4]

| Syrian elephant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull from Gavur Lake Swamp, Turkey | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | Elephas |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †E. m. asurus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Elephas maximus asurus Deraniyagala, 1950[2] | |

Ancient Syrian craftsmen used the tusks of E. m. asurus to make ivory carvings. In Syria, the production of ivory items was at its maximum during the first millennium BC, when the Arameans made splendid ivory inlay for furniture.

Description

Syrian elephants were among the largest Asian elephant subspecies to have survived into historic times, measuring 3.5 metres (11 ft 6 in) or more at the shoulder; on par with the largest reported Indian elephants. Skeletal remains show it did not differ much from the Indian subspecies, except in size. A study of mitochondrial DNA from 3500 year old remains from Gavur Lake Swamp southwest of Kahramanmaraş in Turkey, which represent an apparently wild population, found that they were within extant genetic variation and belonged to the β1 subclade of the major β clade of Asian elephants, β1 being the predominant clade among Indian elephants. They carried an extremely rare mitochondrial haplotype only previously found in a single modern elephant in Thailand, the origin of the haplotype was placed between 3,700–58,700 years ago with a mean estimate of 23,500 years ago, suggesting that the population did not descend from Middle Pleistocene Elephas fossils known from the region and if it was natural it must have arrived in the region as an expansion from the core range of the Asian elephant during the Late Pleistocene or Holocene. The data was inconclusive as to whether the population had a natural or anthropogenic origin.[5]

Distribution and habitat

In Western Asia, the elephants ranged from the mangrove forests of southern Iran, to southern Anatolia, the Syrian steppes and even extended to Israel. Ashurnasirpal II boasted of killing elephants, along with wild oxen and lions.[6]

Controversy

No remains of the Elephas genus are known from the Middle East after 200,000 years ago until 3,500 years ago.[7] This long hiatus makes some scholars suspect that the Asian elephants were artificial introductions to the Middle East, possibly from India, though this is difficult to prove. The extinction date is suggested to be around 700 BC, based on osteoarchaeological and historical evidence. This was possibly due to climactic shifts and changing land use during the early Iron Age[3]

Syrian elephants are frequently mentioned in Hellenistic history; the Seleucid kings, who maintained numerous war elephants, reigned in Syria during that period. These elephants are believed to be Indian elephants (E. m. indicus), which had been acquired by the Seleucid kings during their eastern expansions; or they are believed to be a population of Indian elephants in the Middle East. It is attested by ancient sources such as Strabo[8] and Polybius[9] that Seleucid kings Seleucus I Nicator and Antiochus III the Great had large numbers of imported Indian elephants. Whether these "Indian elephants" were imported due to scarcity of native Syrian elephants, or due to their accomplished training and domestication as war elephants remains unclear.

Hannibal had a war elephant known as "Surus"; it has been suggested to mean "the Syrian". It was said by Cato to have been his best and largest elephant.[10] In that case, the elephant may have been of Seleucid stock. If it were in fact of native Syrian stock, or an imported Indian elephant, remains subject to speculation.[11]

See also

- North African elephant, a subspecies of African elephant that became extinct around the 2nd century BC.

- Persian war elephants

Notes

- Choudhury, A.; Lahiri Choudhury, D.K.; Desai, A.; Duckworth, J.W.; Easa, P.S.; Johnsingh, A.J.T.; Fernando, P.; Hedges, S.; Gunawardena, M.; Kurt, F.; et al. (2008). "Elephas maximus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T7140A12828813. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T7140A12828813.en.

- Deraniyagala, P. E. P. (1951). "Elephas maximus, the elephant od Ceylon". Spolie Zeylanica. 26: 161. ISSN 0081-3745.

- Çakırlar, Canan; Ikram, Salima (2016-05-03). "'When elephants battle, the grass suffers.' Power, ivory and the Syrian elephant". Levant. 48 (2): 167–183. doi:10.1080/00758914.2016.1198068. ISSN 0075-8914.

- Pfälzner, Peter (2016-12-01). "The Elephants of the Orontes". Syria (IV): 159–182. doi:10.4000/syria.5002. ISSN 0039-7946.

- Girdland-Flink, Linus; Albayrak, Ebru; Lister, Adrian M. (2018). "Genetic Insight into an Extinct Population of Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus) in the Near East". Open Quaternary. 4. doi:10.5334/oq.36. ISSN 2055-298X.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2015). Elephants and Kings : An Environmental History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-226-26422-6.

- Lister, Adrian M.; Dirks, Wendy; Assaf, Amnon; Chazan, Michael; Goldberg, Paul; Applbaum, Yaakov H.; Greenbaum, Nathalie; Horwitz, Liora Kolska (September 2013). "New fossil remains of Elephas from the southern Levant: Implications for the evolutionary history of the Asian elephant". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 386: 119–130. Bibcode:2013PPP...386..119L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.05.013.

- Strabo 15.2.1(9)

- Polybius 11.39

- Scullard, H. H. (1953). "Ennius, Cato, and Surus". The Classical Review. 3 (3/4): 140–142. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00995805. JSTOR 703426.

- Charles, Michael B. (2014). "Carthage and the Indian Elephant". L'Antiquité Classique. T. 83: 115–127. doi:10.3406/antiq.2014.3850. JSTOR 90004712.