TWIP steel

Twinning-Induced Plasticity steel which is also known as TWIP steel is a class of austenitic steels which can deform by both glide of individual dislocations and mechanical twinning on the {1 1 1}γ<1 1 >γ system.[1] They have outstanding mechanical properties at room temperature combining high strength (ultimate tensile strength of up to 800 MPa) and ductility (elongation to failure up to 100%) based on a high work-hardening capacity. TWIP steels have mostly high content in Mn (above 20% in weight %) and small additions of elements such C (<1 wt.%), Si (<3 wt.%), or Al (<3 wt.%). The steels have low stacking fault energy (between 20 and 40 mJ/m2) at room temperature. Although the details of the mechanisms controlling strain-hardening in TWIP steels are still unclear, the high strain-hardening is commonly attributed to the reduction of the dislocation mean free path with the increasing fraction of deformation twins as these are considered to be strong obstacles to dislocation glide. Therefore, a quantitative study of deformation twinning in TWIP steels is critical to understand their strain-hardening mechanisms and mechanical properties. Deformation twinning can be considered as a nucleation and growth process. Twin growth is assumed to proceed by co-operative movement of Shockley partials on subsequent {111} planes.

History

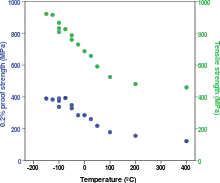

First steel based on plasticity induced by mechanical twinning was found in 1998 which had strength of 800 MPa with a total elongation of above 85%.[2] These values vary with deformation temperature, strain rate and chemical composition.[3][4]

Researchers have shown that increased work hardening attributed to the partitioning of the austenite grains is the main contributing factor to the overall elongation of TWIP steels in which the mechanical strain of twinning have a rather small contribution.[5]

Compositions

TWIP steels usually contain large concentrations of Mn because it is crucial to preserve the austenitic structure based on the ternary system of Fe-Mn-Al [6] and control Stacking Fault Energy (SFE) of the Iron-based alloys.[7][8]

The addition of aluminium to Fe-high Mn TWIP steels is because it increases SFE significantly and therefore stabilizes the austenite against phase transformations which can occur in the Fe-Mn alloys during deformation.[9] Furthermore, it strengthens the austenite by solid-solution hardening.[10]

Properties

Austenitic steels are used widely in many applications because of their excellent strength and ductility combined with good wear and corrosion resistance. High-Mn TWIP steels are attractive for automotive applications due to their high energy absorption, which is more than twice that of conventional high strength steels,[3] and high stiffness which can improve the crash safety.[4]

References

- Harshad Kumar Dharamshi Hansraj Bhadeshia, Sir Robert Honeycombe, Steels, Microstructure and Properties, Third edition, Butterworth-Heinemann publications, Great Britain, p 229. ISBN 0-7506-8084-9

- Oliver Grässel and Georg Frommeyer, Effect of martensitic phase transformation and deformation twinning on mechanical properties of Fe–Mn–Si–Al steels, Material Science and Technology, Vol. 14 (1998) No. 12, pp. 1213-1216. doi:10.1179/026708398790300891

- Georg Frommeyer, Udo Brüx and Peter Neumann, Supra-Ductile and High-Strength Manganese-TRIP/TWIP Steels for High Energy Absorption Purposes, ISIJ International, Vol. 43 (2003) pp. 438-446.

- Oliver Grässel, Lars Krüger, Georg Frommeyer and Lothar Werner Meyer, High Strength Fe-Mn-(Al,Si) TRIP/TWIP Steels Development -Properties-Application, International Journal of Plasticity, Vol. 16 (2000), pp. 1391-1409. doi:10.1016/S0749-6419(00)00015-2

- Bo Qin and Harshad Kumar Dharamshi Hansraj Bhadeshia, Plastic strain due to twinning in austenitic TWIP steels, Materials Science and Technology, Vol. 24 (2008) No. 8, pp. 969-973. doi:10.1179/174328408X263688

- Sato K, Tanaka K & Inoue, Determination of the a/g Equilibrium in the Iron Rich Portion of the Fe-Mn-Al System, ISIJ International, Vol. 29 (1989), pp. 788-792.

- P.Y. Volosevich , V.N. Grindnev and Y.N. Petrov, Manganese Influence on Stacking-Fault Energy in Iron-Manganese Alloys, Physics of Metals and Metallography, Vol. 42 (1976), pp. 126 -130.

- Y.K. Lee and C.S. Choi, Driving Force for γ→ε Martensitic Transformation and Stacking Fault Energy of γ in Fe-Mn Binary System, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, Vol. 31A (2000), pp. 355-360. doi:10.1007/s11661-000-0271-3

- Jianfeng Wan, Shipu Chen, T.Y. Hsu and Xu Zuyao, The stability of transition phases in Fe-Mn-Si based alloys, CALPHAD, Vol. 25 (2001) , pp. 355-362. doi:10.1016/S0364-5916(01)00055-4

- J. Charles, A. Berghézan and A. Lutts, Structural and Mechanical Properties of High-Alloy Manganese-Aluminum Steels, Journal de Physique Colloques, Vol. 43 (1982), pp. C4-435. doi:10.1051/jphyscol:1982466