Tarikh al-fattash

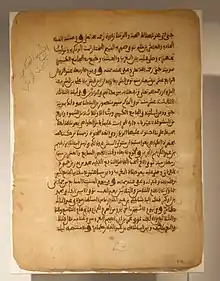

The Tarikh al-fattash is a West African chronicle written in Arabic in the second half of the 17th century. It provides an account of the Songhay Empire from the reign of Sonni Ali (ruled 1464-1492) up to 1599 with a few references to events in the following century. The chronicle also mentions the earlier Mali Empire. It and the Tarikh al-Sudan, another 17th century chronicle giving a history of Songhay, are together known as the Timbuktu Chronicles.[1]

The French scholars Octave Houdas and Maurice Delafosse published a critical edition in 1913. It has been argued that this edition conflates the text from an early incomplete manuscript with that of a re-written forgery produced early in the 19th century. The Tarikh was originally believed to have been written by Mahmud Kati but this has been questioned and Ibn al-Mukhtar, a grandson of Mahmud Kati, is now believed to have been the author.

Discovery and publication

During his visit to Timbuktu in 1895 the French journalist Félix Dubois learnt of the chronicle but was unable to obtain a copy.[2] Most copies of the manuscript had been destroyed early in the 19th century by the order of the Fula[3] leader Seku Amadu, but in 1911 an old manuscript was located in Timbuktu that was missing some of the initial pages. A copy was made and sent to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris (MS No. 6651).[4][5] The original Timbuktu version is designated as Manuscript A while the copy is Manuscript B. A year later a seemingly complete manuscript was located in Kayes. A copy of this manuscript, which includes the name of an author, Mahmud Kati, is designated as Manuscript C. As well as the initial chapter, Manuscript C contains various additions and deletions compared to Manuscript A.[6]

After Octave Houdas and Maurice Delafosse had completed a translation of the Tarikh al-fattash they received a further manuscript that had been acquired by the French traveller Albert Bonnel de Mézières in Timbuktu in September 1913.[7] The preface of this anonymous 24 page document announced that it was written at the request of Askiya Darwud b. Harun. He is known to have reigned in Timbuktu between 1657 and 1669. The text of the manuscript is closely related to the Tarikh al-fattash and presents similar material in a similar order. It includes an introduction which differs from that in Manuscript C, followed by text that is either identical to Manuscript A or is an abridged version of that contained in Manuscript A, missing many of the details.[8]

In 1913 Houdas and Delafosse published a critical edition of the Arabic text of the Tarikh al-fattash together with a translation into French. In the volume containing the French translation they included, as Appendix 2, a translation into French of the unique portions of the 24 page manuscript. However, the corresponding Arabic text was not included in the volume containing the Arabic text of the other manuscripts.[9]

Difficulties with the text

There are some obvious problems with the text published by Houdas and Delafosse. The biographical information for Mahmud Kati (in Manuscript C only) suggests that he was born in 1468, while the other important 17th century chronicle, the Tarikh al-Sudan, gives the year of his death (or someone with the same name) as 1593. This would correspond to an age of 125 years.[10] In addition, there are prophecies made in the initial chapter (Manuscript C only) concerning the coming of the last of the twelve caliphs predicted by Muhammad. He will be Ahmad of the (Fulani) Sangare tribe in Massina. Seku Amadu belonged to this tribe and thus the prophecy was fulfilled.[11]

In 1971 the historian Nehemia Levtzion published an article in which he argued that Manuscript C was a forgery produced during the time of Seku Amadu in the first quarter of the 19th century. He suggested that the real author of the manuscript (Manuscript A) was Ibn al-Mukhtar, a grandson of Mahmud Kati and that the chronicle was probably written soon after 1664.[12]

Levtzion also suggested that the text included as Appendix 2 of the French translation might correspond to an earlier version of Manuscript A, before the manuscript was expanded by members of the Kati family. Unfortunately the modern study of the Tarikh al-fattash is handicapped by the disappearance of the Arabic manuscript corresponding to Appendix 2 of the French translation.[13]

In 2015 based upon analysis of other manuscripts not explored by previous researchers, professor of African history Mauro Nobili and others argued that the work published by Houdas and Delafosse is in fact a conflation of two separate works, that he names the Tarikh Ibn al-Mukhtar, being the chronicle written by Ibn al-Mukhtar, and the actual Tarikh al-fattash, being Appendix 2 of Houdas' and Delafosse's Chronique de Chercher and called the Notice Historique by professor Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias in earlier work from 2008 plus the text of MS A and MS B used by Houdas and Delafosse.[14][15][16]

Origin of the Kingdom of Mali

The Soninke author of Ta'rikh al-Fattash, Ibn al-Mukhtar, recorded the oral tradition surrounding the origin of the Mali kingdom four hundred years earlier. He states: "The kingdom of Mali rose to power only after the fall of the kingdom of Kaya-Magha, ruler of the whole western region. Until then the king of Mali was merely one of the vassals of the Kaya-Magha, one of his officials and ministers. Kaya-Mahga in the Wa'Kore (Soninke) language means 'king of gold'. ... The name of Kaya-Magha's capital was Qunbi."[17][18]

Notes

- Hale 2007, p. 24.

- Dubois 1896, p. 302. Dubois gave the title as Fatassi.

- In French: Peul; in Fula: Pullo.

- "Arabe 6651. Taʾrīḫ al-fattāš". Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Arabe 6651: Taʾrīḫ al-fattāš fī aḫbār al-buldān wa-al-ğuyūš wa-akābir al-nās (in Arabic and French), Gallica.

- Houdas & Delafosse 1913, pp. vii-xi Vol. 2; Levtzion 1971

- Houdas & Delafosse 1913, p. 326.

- Levtzion 1971, p. 580.

- Houdas & Delafosse 1913.

- Houdas & Delafosse 1913, pp. xvii-xviii.

- Houdas & Delafosse 1913, p. 18.

- Levtzion 1971.

- Levtzion 1971, pp. 580-582.

- Nobili 2018, p. 201.

- Nobili & Shahid 2015.

- de Moraes Farias 2008.

- Levtzion 1973, p. 18.

- Houdas & Delafosse 1913, pp. 75-76.

References

- Dubois, Felix (1896). Timbuctoo the mysterious. White, Diana (trans.). New York: Longmans.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Houdas, Octave; Delafosse, Maurice, eds. (1913). Tarikh el-fettach par Mahmoūd Kāti et l'un de ses petit fils (2 Vols.). Paris: Ernest Leroux.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Volume 1 is the Arabic text, Volume 2 is a translation into French. Reprinted by Maisonneuve in 1964 and 1981. The French text is also available from Aluka but requires a subscription.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1971). A seventeenth-century chronicle by Ibn al-Mukhtār: A critical study of "Ta'rīkh al-fattāsh" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 34. pp. 571–593. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00128551. JSTOR 613903.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-8419-0431-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nobili, Mauro (2018). "New reinventions of the Sahel: reflections on the tārikh genre in the Timbuktu historiographical production, seventeenth to twentieth centuries". In Green, Toby; Rossi, Benedetta (eds.). Landscapes, Sources and Intellectual Projects of the West African Past: Essays in Honour of Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-38018-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nobili, Mauro; Shahid, Mohamed (2015). "Towards a new study of the so-called Tārīkh al-fattāsh". History in Africa. 42: 37–73. doi:10.1017/hia.2015.18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Moraes Farias, Paulo Fernando (2008). "Intellectual innovation and reinvention of the Sahel: the seventeenth-century Timbuktu chronicles". In Shamil, Jeppie; Diagne, Suleymane Bachir (eds.). The Meanings of Timbuktu. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press. pp. 95–107. ISBN 978-0-7969-2204-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hale, Thomas A. (2007). Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253219619.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Hunwick, John O. (2001). "Studies in Ta'rīkh al-fattāsh, III: K'ati origins" (PDF). Sudanic Africa. 11: 111–114.

- Wise, Christopher; Taleb, Hala Abu, eds. and trans. (2011). The Timbuktu Chronicles, 1493-1599: Al Hajj Mahmud Kati's Tarikh al-fattash. Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press. ISBN 978-1-59221-809-7.

- Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Arabe 6651: Taʾrīḫ al-fattāš fī aḫbār al-buldān wa-al-ğuyūš wa-akābir al-nās.