Tayma

Tayma /ˈtaɪmə/ (Arabic: تيماء) or Tema /ˈtiːmə/ Teman/Tyeman/Yeman (Habakkuk 3:3) is a large oasis with a long history of settlement, located in northwestern Saudi Arabia at the point where the trade route between Yathrib (Medina) and Dumah (al-Jawf) begins to cross the Nefud desert. Tayma is located 264 km southeast of the city of Tabouk, and about 400 km north of Medina. It is located in the western part of An Nafud desert.

Tayma

تيماء Tema | |

|---|---|

Tayma | |

| Coordinates: 27°37′47″N 38°32′38″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Tabuk province |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

History

Recent archaeological discoveries show that Tayma has been inhabited since at least the Bronze Age. In 2010, the Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities announced the discovery of a rock near Tayma bearing an inscription of Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses III. This was the first confirmed find of a hieroglyphic inscription on Saudi soil. Based on this discovery, researchers have hypothesized that Tayma was part of an important land route between the Red Sea coast of the Arabian Peninsula and the Nile Valley.

The oldest mention of the oasis city appears as "Tiamat" in Assyrian inscriptions dating as far back as the 8th century BC. The oasis developed into a prosperous city, rich in water wells and handsome buildings. Tiglath-pileser III received tribute from Tayma, and Sennacherib named one of Nineveh's gates as the Desert Gate, recording that "the gifts of the Sumu'anite and the Teymeite enter through it." It was rich and proud enough in the 7th century BC for Jeremiah to prophesy against it (Jeremiah 25:23). It was ruled then by a local Arab dynasty, known as the Qedarites. The names of two 8th-century BC queens, Shamsi and Zabibei, are recorded.

The last Babylonian king Nabonidus conquered Tayma and for ten years of his reign retired there for worship and looking for prophecies, entrusting the kingship of Babylon to his son, Belshazzar. Taymanitic inscriptions also mention that people of Tayma fought wars with Dadān.[1]

Cuneiform inscriptions possibly dating from the 6th century BC have been recovered from Tayma. It is mentioned several times in the Old Testament. The biblical eponym is apparently Tema, one of the sons of Ishmael, after whom the region of Tema is named.

According to Arab tradition, Tayma was inhabited by a Jewish community during the late classical period, though whether these were exiled Judeans or the Arab descendants of converts is unclear. During the 1st century AD, Tayma is believed to have been principally a Jewish settlement. The Jewish Diaspora at the time of the Temple’s destruction, according to Josephus, was in Parthia (Persia), Babylonia (Iraq), Arabia, as well as some Jews beyond the Euphrates and in Adiabene (Kurdistan). In Josephus’ own words, he had informed “the remotest Arabians” about the destruction.[2] So, too, in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, Tayma is often referred to as a fortified city belonging to the Jews, just as the anonymous Arab poet has described:[3]

Unto God will I make my complaint heard, but not unto man; because I am a sojourner in Taymā, Taymā of the Jews![4]

As late as the 6th century AD, Tayma was the home of the wealthy Jew, Samau’al ibn ‘Ādiyā.[5][6]

Tayma and neighboring Khaybar were visited by Benjamin of Tudela some time around 1170 who claims that the city was governed by a Jewish prince. Benjamin was a Jew from Tudela in Spain. He travelled to Persia and Arabia in the 12th century.

In the summer of 1181 Raynald of Châtillon attacked a Muslim caravan near Tayma, despite a truce between Sultan Saladin and king Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, during a raid of the Red Sea area. [7]

The historic significance of Tayma is centralized around the existence of an oasis which used to attract people and animals, its location that served as a commercial passage and the residence of the Babylonian king Nabonidus in the mid-6th century BCE.[8]

Climate

In Tayma, there is a desert climate. Most rain falls in the winter. The Köppen-Geiger climate classification is BWh. The average annual temperature in Tayma is 21.8 °C (71.2 °F). About 65 mm (2.56 in) of precipitation falls annually.

| Climate data for Tayma | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.2 (75.6) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.9 (98.4) |

37.1 (98.8) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

28.8 (83.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9 (0.4) |

4 (0.2) |

10 (0.4) |

9 (0.4) |

3 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

7 (0.3) |

16 (0.6) |

7 (0.3) |

65 (2.6) |

| Source: Climate data | |||||||||||||

Archaeology

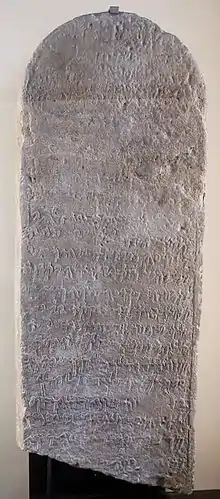

The site was first investigated and mapped by Charles M. Doughty in 1877.[9] The Tayma stele discovered by Charles Huber in 1883, now at the Louvre, lists the gods of Tayma in the 6th century BC: Ṣalm of Maḥram and Shingala and Ashira. This Ashira may be Athirat/Asherah.

Archeological investigation of the site, under the auspices of the German Archaeological Institute, is ongoing.[10][11]

Clay tablets and stone inscriptions using Taymanitic script and language were found in ruins and around the oasis. Nearby Tayma was a Sabaean trading station, where Sabaean inscriptions were found.

Economy

Historically, Tayma is known for growing dates.[12] The oasis also has produced rock salt, which was distributed throughout Arabia.[13] Tayma also mined alum, which was processed and used for the care of camels.[14]

Points of interest

- Qasr Al-Ablaq castle is located on the southwest side of the city. It was built by Jewish poet and warrior Samuel ibn 'Adiya and his grandfather 'Adiya in the 6th century AD.

- The Qasr Al-Hamra palace was built in the 7th century BC.

- Tayma has an archaeologically significant perimeter wall built around 3 sides of the old city in the 6th century BC.

- Qasr Al-Radhm

- Haddaj Well

- Cemeteries

- Many Aramaic, Lihyanite, Thamudic, Nabataean language inscriptions, around Tayma

- Qasr Al-Bejaidi

- Al-Hadiqah Mound

- Many museums. Although Tayma has museums of its own such as the "Tayma Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography", many artifacts from its history have been spread to other museums. Early finds such as the "Tayma Stele" are at the Louvre in Paris among others while large museums of national importance in Saudi Arabia, such as the National Museum of Saudi Arabia in Riyadh and the Jeddah Regional Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography also have significant collections of items from or related to ancient Tayma.

See also

Notes

- "krc2.orient.ox.ac.uk" (PDF).

- Josephus. The Jewish War. Translated by Whiston, William. 1.1.5 – via PACE: Project on Ancient Cultural Engagement. Greek: Ἀράβων τε τοὺς πορρωτάτω = Preface to Josephus' De Bello Judaico, paragraph 2, “the remotest Arabians” (lit. “the Arabian [Jews] that are further on”).

- Yāqūt, Šihāb al-Dīn ibn ‘Abd Allah al-Ḥamawī (1995). "Taimā". Mu'jam al-Buldān. II. Beirut. p. 67; cf. al-Ṭabbā‘ in his Forward to Samaw’al 1997, p. 7

- Yaqut, Šihāb al-Dīn ibn ‘Abd Allah al-Ḥamawī (1995). Mu'jam al-Buldān. Beirut: Dār Ṣādir. p. 67.

- David Samuel Margoliouth, A poem attributed to Al-Samau’al, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society: London, 1906

- A‘šā (1968). Muḥammad Muḥammad Ḥusayn (ed.). Dīwān al-a‘šā al-kabīr maymūn bn qays: šarḥ wa-ta‘līq (in Arabic). Beirut. pp. 214, 253.

- Gary La Viere Leiser, The Crusader Raid in the Red Sea in 578/1182-83, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, vol. 14, pp. 87-100, 1977

- "Tayma - Arabian Rock Art Heritage". Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- Raymond P. Dougherty, A Babylonian City in Arabia, American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 296-312, 1930

- A. Hausleiter, L'oasis de Tayma, pp. 218-239 in A.I. al-Ghabban et al. (eds), Routes d'Arabie. Archéologie et Histoire du Royaume Arabie-Saoudite, Somogy, 2010

- A. Hausleiter, La céramique du début de l'âge dur Fer, pp. 240 in A.I. al-Ghabban et al. (eds), Routes d'Arabie. Archéologie et Histoire du Royaume Arabie-Saoudite, Somogy, 2010

- Prothero 1920, p. 83.

- Prothero 1920, p. 97.

- Prothero 1920, p. 98.

References

- Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 83.

External links

- Deutsches Archäologisches Institut: Tayma

- Nabatea: The 12 Tribes of Ishmael: Tema

- about Jouf district

- Verse account of Nabonidus, translation at Livius.org

- Chronicle of Nabonidus, translation at Livius.org

- Travel through the province of Tabuk, Splendid Arabia: A travel site with photos and routes