The Coal Question

The Coal Question; An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines is a book that economist William Stanley Jevons wrote in 1865 to explore the implications of Britain's reliance on coal.[1][2] Given that coal was a finite, non-renewable energy resource, Jevons raised the question of sustainability. "Are we wise," he asked rhetorically, "in allowing the commerce of this country to rise beyond the point at which we can long maintain it?" His central thesis was that the supremacy of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland over global affairs was transitory, given the finite nature of its primary energy resource. In propounding this thesis, Jevons covered a range of issues central to sustainability, including limits to growth, overpopulation, overshoot,[3] energy return on energy input (EROEI), taxation of energy resources, renewable energy alternatives, and resource peaking—a subject widely discussed today under the rubric of peak oil.

Cover of the second edition | |

| Author | William Stanley Jevons |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Macmillan & Co. London |

Publication date | 1865 |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | 978-0-678-00107-3 |

The significance of coal

Jevons introduces the first chapter of The Coal Question with a succinct description of coal's wonders and of society's insatiable appetite for it:

"Coal in truth stands not beside but entirely above all other commodities. It is the material energy of the country — the universal aid — the factor in everything we do. With coal almost any feat is possible or easy; without it we are thrown back into the laborious poverty of early times. With such facts familiarly before us, it can be no matter of surprise that year by year we make larger draughts upon a material of such myriad qualities — of such miraculous powers."

"...new applications of coal are of an unlimited character. In the command of force, molecular and mechanical, we have the key to all the infinite varieties of change in place or kind of which nature is capable. No chemical or mechanical operation, perhaps, is quite impossible to us, and invention consists in discovering those which are useful and commercially practicable...."

Jevons further argues that coal is the source of the UK's prosperity and global dominance.

Limits to growth and resource peaking

Because coal was not unlimited, because its access became more difficult with time, and because the demand grew exponentially, Jevons argued that limits or boundaries to prosperity would appear sooner than was generally realized:

"I must point out the painful fact that such a rate of growth will before long render our consumption of coal comparable with the total supply. In the increasing depth and difficulty of coal mining we shall meet that vague, but inevitable boundary that will stop our progress."

In Jevons' day, British geologists were estimating that the country had coal reserves of 90 billion tons. Jevons believed that extraction of much of this amount would prove to be uneconomical. But, even if the entire quantity could be extracted, Jevons argued, exponential economic growth could not continue unabated.

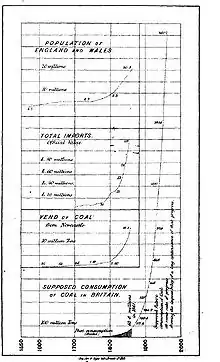

Using historical production estimates, Jevons showed that for the previous 80 years production had grown at a relatively consistent rate of 3.5% per year, or 41% per decade. If this growth rate were to continue, production would grow from approximately 100 million tons in 1865 to more than 2.6 billion tons in 100 years. Jevons then calculated that, in that case, the country would produce approximately 100 billion tons within that period.[4] In short, resources were not sufficient for even 100 years, and long before the 100 years point, the growth rate, which was the measure of prosperity, would have to decline. At some point, production would simply hit a peak, which itself meant dire consequences:

"Suppose our progress to be checked within half a century, yet by that time our consumption will probably be three or four times what it now is; there is nothing impossible or improbable in this; it is a moderate supposition, considering that our consumption has increased eight-fold in the last sixty years. But how shortened and darkened will the prospects of the country appear, with mines already deep, fuel dear, and yet a high rate of consumption to keep up if we are not to retrograde."

Even before the peak was reached, high extraction costs could cause the UK to lose the competitive advantage it currently enjoyed in manufacturing and shipping.

British coal production did in fact peak in 1913, but at 292 million tons, about half the amount Jevons' extrapolation suggested. Just under a third of this was exported. Since then, production has dropped to less than 20 million tons.[5] Current UK resources are estimated at about 400 million tons.[6]

Population and the "Malthus Doctrine"

According to Jevons, coal depletion had serious ramifications for population growth. The population of the UK had increased by more than 10% each decade for the prior 70 years, not surprising given that coal production was growing at 40% per decade, meaning that the per capita wealth was growing.

"For the present our cheap supplies of coal, and our skill in its employment, and the freedom of our commerce with other wide lands, render us independent of the limited agricultural area of these islands, and take us out of the scope of Malthus' doctrine. We are growing rich and numerous upon a source of wealth of which the fertility does not yet apparently decrease with our demands upon it. Hence the uniform and extraordinary rate of growth which this country presents. We are like settlers spreading in a rich new country of which the boundaries are yet unknown and unfelt."

However, as the growth in coal production slowed, the population growth might easily surpass the production growth, leading to a drop in living conditions:

"Now population, when it grows, moves with a certain uniform impetus, like a body in motion; and uniform progress of population, as I have fully explained before, is multiplication in a uniform ratio. But long-continued progress in such a manner is altogether impossible — it must outstrip all physical conditions and bounds; and the longer it continues, the more severely must the ultimate check be felt. I do not hesitate to say, therefore, that the rapid growth of our great towns, gratifying as it is in the present, is a matter of very serious concern as regards the future."

In contrast to Malthus's view that resource growth was linear, Jevons took resource growth as being exponential, like population. This modification of Malthus's theory did not alter the conclusion that unrestrained population growth would inevitably surpass the nation's ability to expand its resources. Prosperity, in terms of per capita consumption, would therefore fall. Moreover, because the primary resource was non-renewable, the fall would be more dramatic than Malthus envisioned:

A farm, however far pushed, will under proper cultivation continue to yield forever a constant crop. But in a mine there is no reproduction, and the produce once pushed to the utmost will soon begin to fail and sink towards zero. So far then as our wealth and progress depend upon the superior command of coal we must not only stop—we must go back.

The Jevons Paradox

Given that energy depletion posed long-term dangers for society, Jevons analyzed possible mitigation measures. In so doing, he considered the phenomenon that has come to be known as Jevons paradox. As he wrote:

" It is wholly a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth."

Jevons described the historical development of engine technology and argued that the great increase in the UK's consumption of coal was due to the efficiency (or "economy") brought about by technological innovations, with particular credit going to James Watt's 1776 invention of the steam engine. Like many innovations that followed, such as improved methods for smelting iron, greater economy broadened usage and led to increased energy consumption.

"Whatever, therefore, conduces to increase the efficiency of coal, and to diminish the cost of its use, directly tends to augment the value of the steam-engine, and to enlarge the field of its operations."

Jevons also considered and rejected other measures that might reduce consumption, such as coal taxes and export restrictions. Similarly, although he deplored the wasteful practice of burning away low quality coal at the mine site, he did not support conservation legislation.

An alternative that he did consider practical was tightened government fiscal policy, based on using tax revenue to reduce the national debt. Tightened fiscal policy would have the effect of slowing economic growth, thereby slowing coal consumption, at least until the debt was erased. Still, Jevons admitted that the overall impact of such a measure, even if it were implemented, would be minimal. In short, the prospect that society would voluntarily reduce consumption was dim.

Energy alternatives

Jevons considered the feasibility of alternative energy sources, foreshadowing modern debates on the subject. Regarding wind and tidal forces, he explained that such sources of intermittent power could be made more useful if the energy were stored, for example by pumping water to a height for subsequent use as hydro power. He reviewed biomass, namely timber, and commented that forests covering all of the UK could not supply energy equal to the current coal production. He also mentioned possibilities for geothermal and solar power, pointing out that if these sources did become useful, the UK would lose its competitive advantages in global industry. He was not aware of the future importance of natural gas or petroleum as prime energy sources since they were developed after his book was published.

Regarding electricity, which he pointed out was not an energy source but a means of energy distribution, Jevons noted that hydroelectric power was feasible but that reservoirs would face the problem of silt build-up. He discounted hydrogen generation as a means of electricity storage and distribution, calculating that the energy density of hydrogen would never make it practical. He predicted that steam would remain the most efficient means of generating electricity.

Social responsibility in time of prosperity

Jevons held that despite the desirability of reducing coal consumption, the outlook for implementing significant constraints was dim. Still, the UK's prosperity should at least be seen as imposing responsibilities on the current generation. In particular, Jevons proposed applying the current wealth to righting social ills and to creating a more just society:

"We must begin to allow that we can do today what we cannot so well do tomorrow....

"Reflection will show that we ought not to think of interfering with the free use of the material wealth which Providence has placed at our disposal, but that our duties wholly consist in the earnest and wise application of it. We may spend it on the one hand in increased luxury and ostentation and corruption, and we shall be blamed. We may spend it on the other hand in raising the social and moral condition of the people, and in reducing the burdens of future generations. Even if our successors be less happily placed than ourselves they will not then blame us."[7]

Jevons also articulated several social ills that particularly concerned him:

"The ignorance, improvidence, and brutish drunkenness of our lower working classes must be dispelled by a general system of education, which may effect for a future generation what is hopeless for the present generation. One preparatory and indispensable measure, however, is a far more general restriction on the employment of children in manufacture. At present it may almost be said to be profitable to breed little slaves and put them to labour early, so as to get earnings out of them before they have a will of their own. A worse premium upon improvidence and future wretchedness could not be imagined."

Global developments after Jevons

As Jevons predicted, coal production could not grow exponentially forever. UK production peaked in 1913, and the country lost its global superiority to a new giant of energy production, the United States, a turn of events that was also predicted by Jevons. The UK had by then developed oil resources in the Middle East and increasingly used the fuel for power generation.

Although UK production could not continue to grow at the annual rate of 3.5%, the world's fossil fuel consumption did grow at this rate until about 1970. According to Jevons, UK coal production in 1865 was estimated as being equal to production in the rest of the world, giving a rough world estimate of 200 million tons. According to the US Department of Energy, global fossil fuel consumption in 1970 was 200 Quad BTU, or 7.2 billion tons coal equivalent.[8] Thus, consumption grew by a factor of 36, representing average annual exponential growth over 105 years of about 3.4%.[9] In the 34 subsequent years, to 2004, consumption grew by a factor of 2.1, or 2.2% per year, an indication, according to organizations such as ASPO that global energy resources are thinning.[10]

The quantity of the world's remaining energy resources is a matter of dispute and serious concern. Between 2005 and 2007, despite the trebling of oil prices, oil production remained relatively flat,[11] a sign according to many that oil production has peaked.[12] Studies by Dave Rutledge of the California Institute of Technology,[13] and by the Energy Watch Group of Germany[14] indicate that global coal production will also peak within the current generation, perhaps as soon as 2030. A parallel study by the Energy Watch Group also indicates the limited supply of uranium; this report states that like UK coal production 200 years ago, the production of uranium has first targeted high quality ores, and remaining sources are less dense and more difficult to access.

Fetter states that at least 230 years of proven uranium reserves are available at present worldwide rates of consumption, and using uranium extraction from seawater, up to 60,000 years of uranium are available. Further, using advanced breeder reactors and nuclear reprocessing, the 230 years of proven uranium reserves may be extended up to 30,000 years; similar gains are achievable from the 60,000 years of uranium reserves from seawater.[15]

References

- See Jevons, William Stanley (1865). The Coal Question; An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines (1 ed.). London & Cambridge: Macmillan & Co. Retrieved 12 November 2014. via Google Books

- See Jevons, William Stanley (1866). The Coal Question; An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines (2 ed.). London: Macmillan & Co. Retrieved 12 November 2014. via Google Books

- Catton, William (1982-06-01). Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-00988-4.

- "Energy Trends and Quarterly Energy Prices" (PDF). UK Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform. December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-04.

- 2007 Annual Report of the UK Coal Authority.

- Jevons, W. Stanley, The Coal Question, 2nd revised edition, 1866, Macmillan and Co., page xxv

- World Primary Energy Production by Source, 1970-2004

- December 2007 International Petroleum Monthly Archived 2007-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- see http://www.simmonsco-intl.com/files/AnotherNailintheCoffin.pdf%5B%5D

- "Dave Rutledge website". Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- Energy Watch Group Reports

- Fetter, Steve (2009-01-26). "How Long Will The World's Uranium Supplies Last". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2011-03-19. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

Sources

- Malthus, An Essay On The Principle Of Population (1798 1st edition) with A Summary View (1830), and Introduction by Professor Antony Flew. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-043206-X.

- Joel E. Cohen, How Many People Can the Earth Support?, 1995, W. W. Norton & Company.

- Howard Bucknell III. Energy and the National Defense, 1981, University of Kentucky Press

- William Catton, Overshoot, 1982, University of Illinois Press.

- Mathis Wackernagel, Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth, 1995, New Society Publishers.

- Tim Flannery, The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australian Lands and People, 2002, Grove Press.

- Michael Williams, Deforesting the Earth: From Prehistory to Global Crisis, 2002, University of Chicago Press.

- Garrett Hardin, The Ostrich Factor: Our Population Myopia, 1999, Oxford University Press.

- Walter Youngquist, Geodestinies: The Inevitable Control of Earth Resources over Nations & Individuals, 1997, National Book Company.

- Heinberg, Richard. Powerdown: Options and Actions for a Post-Carbon World, 2004, New Society Publishers.

- Kunstler, James Howard. The Long Emergency: Surviving the End of the Oil Age, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-first Century, 2005, Atlantic Monthly Press.

- Odum, Howard T. and Elisabeth C. A Prosperous Way Down: Principles and Policies, 2001, University Press of Colorado.

- Stanton, The rapid growth of human populations 1750–2000, 2003.

- Bartlett, A., Scientific American and the Silent Lie, 2004

- Meadows et al., Limits to Growth: The 30-year Update, 2004.

- Diamond, Jared, Collapse, 2005.