The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie

The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie is a book of recipes collected over a lifetime by Charlotte, Lady Clark of Tillypronie (née Coltman, 1851–1897), and published posthumously in 1909. The earliest recipe was collected in 1841; the last in 1897. The book was edited by the artist Catherine Frances Frere, who had seen two other cookery books through to publication, at the request of Clark's husband.

First edition | |

| Author | Charlotte, Lady Clark Catherine Frances Frere |

|---|---|

| Country | Scotland |

| Subject | 19th century British recipes |

| Genre | Cookery |

| Publisher | Constable & Company |

Publication date | 1909 |

| Pages | xviii + 584 |

The book is considered a valuable compilation of Victorian era recipes. Lady Clark obtained the recipes by asking hostesses or cooks, and then testing each one at Tillypronie. She documented each recipe's source with the name of her source, and often also the date. There is comprehensive coverage of plain British cooking, especially of meat and game, but the book has sections on all aspects of contemporary cooking including bread, cakes, eggs, cooking for invalids, jams, pies, sauces, sweets (puddings) and vegetables. She had lived in Italy and France, and the cuisines of these countries are represented by many dishes, as is Anglo-Indian cooking with a section called "Curries".

The book was enjoyed by Virginia Woolf and acted as a source of inspiration to the cookery writer Elizabeth David.

Context

Tillypronie is a Victorian era house between Ballater and Strathdon in Scotland, just east of the Cairngorms National Park, overlooking the valley of the River Dee; the gardens are open to the public.[1] Lady Clark collected thousands of recipes for her own use between 1841 and 1897;[2] among her house-guests in the 1870s was Henry James, who commented in a letter "I bless the old house on the mountain and its genial and bountiful tenants".[3] Lady Clark was married to the diplomat Sir John Forbes Clark, second baronet.[4][5] Sir John worked in Paris (seeing the 1848 revolution there), moving to Brussels in 1852 and Turin from 1852 to 1855; he married Charlotte in 1851.[4] Living in Europe gave Lady Clark a detailed insight into Italian and French cooking – there are five recipes for Tartare sauce; and she was well informed about Anglo-Indian cookery, with dishes such as "Rabbit Pish-pash".[6] Her approach was to ask her hostess or the cook how any interesting or unusual dish was made, and then to try out the recipe back at Tillypronie to ensure that it worked.[7]

After Lady Clark's death in 1897, her widower invited Catherine Frances Frere (1848–1921), daughter of Sir Henry Bartle Frere, to assemble them into a book, asking:[2]

I have asked you to stand sponsor for the publication of a selection from a number of cookery and household recipes, collected by my late wife – this for two reasons, firstly because I know you to be yourself not a little interested and versed in the science of Brillat Savarin; and secondly, and mainly, because, from your intimate acquaintance with her for many years you can bear testimony to her having been, not the mere "housewife" on culinary things intent, but an exceptionally widely-read woman, gifted with fine literary taste and judgement. ... In this confidence, and in the hope and belief that they may prove of service to many a young matron of like mind with her who made it, I confide the collection to you for your supervision and for publication. Yours sincerely, John F. Clark.[8]

Frere was born in Malcolm Peth, Bombay on 25 September 1848.[9] In later life she lived in Westbourne Terrace, London.[10] The Cookery Book was not Frere's first publication; at the age of 20 she had illustrated her sister Mary's book, Old Deccan Days, Or, Hindoo Fairy Tales Current in Southern India, a compilation of folk tales; their father was at the time Governor of Bombay. The book was popular, going into four editions between first publication in 1868 and 1889.[11] In the Preface to the Cookery Book she denies "the special knowledge of cookery with which Sir John so kindly credits me", but admits she has always been interested in the "study", and that she had seen "two other cookery books through the press for my friend the late Miss Hilda Duckett": these were Hilda's Where is it? of Recipes (1899) and Hilda's Diary of a Cape Housekeeper (1902), both published by Chapman and Hall; but Frere's name had not appeared on their title pages.[12]

Book

Structure

The first edition is of xviii + 584 pages. It is divided into sections as follows, starting immediately after the Table of Contents with no preamble :

- Baking powder, Barm and Yeast

- Beverages

- Bread, Grissini, Porridge and Rolls

- Cakes, &c.

- Cheeses and cheese dishes

- Confectionery

- Curries

- Domestic Recipes

- Eggs

- Fish

- Fish Pies and Puddings

- Fish, Game, Meat and Savoury Creams

- Game

- Invalid Cookery

- Jams, Jellies, Marmalades, Fruit Syrups, &c.

- Meat

- Meat Jellies

- Meat Pies, Puddings and Soufflés

- Melted Butters, Butter Sauces and Savoury Butters

- Omelets

- Paste and Pastry

- Poultry

- Preserved Fruits

- Roux, Browning and Glaze

- Sauces for Fish

- Sauces for Meat

- Sauces for Poultry and Game

- Sauces for Vegetables

- Soups and Broths

- Stuffings

- Sweet Dishes

- Sweet Puddings

- Sweet Sauces

- Vegetables

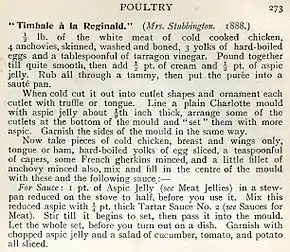

There are no illustrations.

There is an Appendix, under Frere's name, with sections summarized from the RSPCA on how "To spare animals unnecessary pain" and "Bad meat" (which gives advice on the best ways to kill rabbits and birds). The index runs to 31 pages in two columns of small type.

Approach

Each recipe is presented quite plainly, with a title which is numbered if there is more than one recipe for a given dish. There is no list of ingredients: each recipe begins at once, as for instance "Pound the slightly scalded fish, pound also 1/2 lb. of suet shred very fine, and 2 ozs. of stale bread-crumbs, and 1 egg well beaten."[13] Many recipes have a named source, sometimes with a date, as in "Rhubarb Jam. (Mrs. Davidson, Coldstone Manse. 1886.)"[14]

Some of Lady Clark's recipes are very brief, forming little more than notes to herself, as in her

Vegetable Marrow. No. 3. Stuffed—Turin. 'Cousses'.

The Turin vegetable marrows are small and short—perhaps 2 inches long;[lower-alpha 1] they are stuffed with forcemeat, and served in a thick sauce.

They come as a 'frittura' after the soup, and are sometimes called 'Zucchetti à la Piedmontaise.'"[15]

It can be seen that instructions, ingredients and comments are intermixed.

The recipes in each section are listed alphabetically. Some entries are cross-references, for example "'Zucchetti à la Milanaise' and 'à la Piedmontaise.' See Vegetable Marrow."[15]

Editions

For most of the twentieth century there was only one edition, that of 1909, published by Constable:

- Frere, Catherine Frances (editor). (1909) The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie. London: Constable and Company.

This changed in the 1990s:

- (1994) The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie, with an Introduction by Geraldene Holt. Lewes: Southover.

Reception

Contemporary

The feminist author Virginia Woolf reviewed the book in the Times Literary Supplement in 1909, writing that "Cookery books are delightful to read... A charming directness stamps them, with their imperative 'Take an uncooked fowl and split its skin from end to end'[lower-alpha 2] and their massive commonsense which stares frivolity out of countenance".[16][17]

The Spectator review in 1909 speculates that Lady Clark inherited the "practical study of cookery" from her father, "Mr. Justice Coltman" who though "abstemious himself" was "careful to provide a well-furnished table for his guests".[18] The review remarks on

the distinguished origin of many of the recipes. Mr. Ford, of the famous "Handbook to Spain," contributes some few Spanish dishes; there is a recipe for ginger yeast which Miss Nightingale must often have tested;[lower-alpha 3] the poet Rogers tells us how to make a "Poet's Pudding," and Lord Houghton gives directions for a mutton and oyster pudding.[18]

Modern

The cookery writer Elizabeth David describes one of Lady Clark's recipes in her 1970 book Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen as follows:

Thick Parmesan Biscuits. A little-known recipe from The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie...it is for the ideas, the historical aspect and the feeling of authenticity, the certainty that these recipes were actually used and the dishes successful...that this book is so valuable. This recipe is an exceptionally good one...:

- For a dozen biscuits: ¼ lb. plain flour, 2 oz. each of butter and grated Parmesan, the yolk of one egg, salt, cayenne pepper. Rub the butter into the flour, add the cheese, egg and seasonings. Moisten with a little water if necessary. Roll out the dough to the thickness of half an inch. Cut into 1 inch diameter rounds. Arrange on a baking sheet. Bake in the centre or lower centre of a very moderate oven, gas No. 2, or 310–330° F., for just on 20 minutes. Serve hot.[lower-alpha 4]

Lady Clark makes the point that it is the thickness of these biscuits that gives them their character...the biscuits can be stored in a tin and heated up when wanted.[19]

Sue Dyson and Roger McShane, reviewing the book on foodtourist.com, call it "a valuable collection of British recipes"[2] and

important for a number of reasons. The first is that it represents a broad range of recipes that were in common use in households throughout Britain in the 19th century and hence serves to codify the preparation of food at the time. The second is that it is not the work of just one person. Lady Clark was an avid collector of recipes and her work is a compilation form hundreds of home cooks. The third reason why we think it is important is this work of Lady Clark had a deep effect on, and was an inspiration for, the great Elizabeth David.[2]

Dyson and McShane state (after discussing the contents) that "The recipes are not difficult as Lady Clark preferred simplicity and was annoyed with contrivance." They write that "The recipes on meat and poultry are very strong and range over the normal meats such as beef and pork and then on to many game dishes as would be expected of someone living in the highlands of Scotland." They conclude with the recommendation "An excellent addition to your food library!"[2]

Vanessa Kimbell of the Sourdough School writes that Frere carefully catalogued all the recipes, removing any that she could trace to a published source, and comments that they "are all delightfully straight forward".[20] She explains:

There are few keen cooks who do not collect recipes as they go along in life. A friend's cake scribbled down on a scrap of paper, a page torn out and treasured from a newspaper. For Lady Clark of Tillypronie, a well-travelled diplomat's wife, and friend of the American author Henry James, collecting recipes was more than just a keen interest; it was a way of life. Inspired by her father's love of French cuisine, Lady Clark collected cooked and annotated over three thousand pages of manuscripts and recipes between 1841 and 1897, including many from her time spent living in France and Italy.[20]

Kimbell concludes that "This extraordinary book is a delight to cook from. [Frere's] diligence in putting together this vast collection of recipes resulted in one of the most charming, straightforward and thorough recipe books of the late nineteenth century with recipes that are still remarkably very useable today."[20]

In her introduction to the 1994 edition, Geraldene Holt writes that while most cooks collect recipes,[6]

Few though, equal the astonishing feat of Lady Clark of Tillypronie, who filled more than three thousand pages of manuscript, as Catherine Frere says, "not only written over every available margin, but often crossed like a shepherd's plaid", with culinary details and carefully recorded recipes of meals and dishes she enjoyed.[6]

Holt observes of the book that

What strikes me so forcibly is the modernity of Lady Clark's food. Her preference for simple cooking with unblemished, distinctive flavours – her worst criticism of a dish is that it tastes dull – makes her food attractive even a century later. And her eclecticism, born of her well-travelled childhood and life as the wife of a diplomat, produced dishes that still appeal to present-day tastes.[6]

In her book A Caledonian Feast, Annette Hope calls Lady Clark "admirable"[21] and writes that her

cookery book (a collector's item) epitomises the gastronomic life of late Victorian aristocracy. Even before her marriage Lady Clark had travelled much with her family, in France and Italy; there she developed an interest in good food which, unlike that of many contemporaries, was based much less on greed and a predilection for ostentation than on a delicate appreciation of quality.[21]

Hope adds that Lady Clark's

personal jottings – sometimes no more than aides-mémoire – unconsciously convey the world of the late Victorian hostess in London, abroad, and at home in Tillypronie. Because the provenance of most recipes is noted, her pages are peopled with shadowy figures, some of whose names we recognise, others quite unknown, but all united in the confraternity of what James Boswell called the "Cooking Animal".[21]

Notes

- These are now called courgettes or zucchini.

- This is from page 261 in the recipe for "Chicken Galantine. No. 1. (Cataldi.)"

- The recipe on page 2 is from "Mr. Nightingale, Leahurst", Florence Nightingale's father; his Leahurst estate was in Derbyshire.

- The recipe is on page 66, "Parmesan Biscuits—Thick".

References

- "Tillypronie". Scotlands Gardens. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- Dyson, Sue; McShane, Roger. "The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie by Charlotte Clark". FoodTourist. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- James, Henry; Edel, Leon (1980). Letters. Harvard University Press. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-674-38782-9.

- "Sir John Forbes Clark (Obituary)". The Times. 14 April 1910.

- ‘CLARK, Sir John Forbes’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2015; online edition, Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014

- Holt, Geraldene. "Essays and Introductions". Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- "The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie". Abe Books. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Frere, 1909. pp. vii–viii

- Frere, Catherine Frances. "British India Office Ecclesiastical Returns – Births & Baptisms Transcription". FindMyPast. Retrieved 7 December 2014.(subscription required)

- Frere, Catherine Frances. "GWR Shareholders Transcription". FindMyPast. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- "Old Deccan Days, Or, Hindoo Fairy Tales Current in Southern India". Goodreads. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- Frere, 1909. pp. viii–ix

- Frere, 1909. p. 127

- Frere, 1909. p. 176

- Frere, 1909. p. 542

- McNeillie, A. (1986). The Essays of Virginia Woolf, volume 1: 1904–1912. Hogarth Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-701-20666-6.

- Woolf, Virginia (25 November 1909). "The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie". Times Literary Supplement.

- Anon (27 November 1909). "The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie". The Spectator. p. 25. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- David, Elizabeth (2000) [1970]. Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen. Grub Street. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-1-902-30466-3.

- Kimbell, Vanessa. "The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie – 1909". The Sourdough School. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Hope, Annette (2010) [1987]. A Caledonian Feast. Canongate Books. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-84767-442-5.

Bibliography

- Frere, Catherine Frances (editor). (1909) The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie. London: Constable and Company. OCLC 752897816.

- Frere, Catherine Frances (editor). (1994) The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie, with an Introduction by Geraldene Holt. Lewes: Southover. OCLC 751679281. ISBN 978-1-870-96210-0.