The Creation of the Humanoids

The Creation of the Humanoids is a 1962 American science fiction film release, directed by Wesley Barry and starring Don Megowan, Erica Elliot, Frances McCann, Don Doolittle and Dudley Manlove. The film is not based on the plot of Jack Williamson's novel The Humanoids, to which it bears little resemblance, but on an original story and screenplay written by Jay Simms.[1]

| The Creation of the Humanoids | |

|---|---|

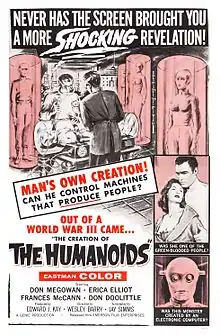

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Wesley Barry |

| Produced by | Wesley Barry Edward J. Kay |

| Written by | Jay Simms |

| Starring | Don Megowan Erica Elliot Frances McCann Don Doolittle George Milan Dudley Manlove |

| Music by | Edward J. Kay |

| Cinematography | Hal Mohr |

| Edited by | Ace Herman (as Leonard W. Herman) |

| Distributed by | Emerson Film Enterprises |

Release date |

|

Running time | 84 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

In a post-nuclear-war society, blue-skinned, silver-eyed human-like robots have become a common sight as the surviving population suffers from a decreasing birth rate and has grown dependent on their assistance. A fanatical organization tries to prevent the robots from becoming too human, fearing that they will take over. Meanwhile, a scientist experiments with creating human replicas that have genuine emotions and memories.

Plot

The Earth is suffering the aftereffects of a nuclear war that destroyed 92 percent of humanity. Lingering radiation has caused the birth rate to fall below replacement level and the population continues to decline. A robotic labor force maintains a high standard of living for the survivors and the humanoids of the title are an advanced type of robot created to directly serve and otherwise work closely with human beings. These humanoids are built with artificial, ultra-logical personalities and they appear human except for their blue-gray "synthe-skin", metallic eyes and lack of hair. The humanoids periodically visit recharging stations they call "temples" where they also exchange all information acquired since their last visit with a central computer they call "the father-mother".

A quasi-racist human organization named The Order of Flesh and Blood is opposed to the humanoids, which the members disparagingly refer to as "clickers". The Order believes the humanoids are planning to take over the world and are a threat to the very survival of the human race. The Order does not stop at illegal violent actions, including bombings. At one meeting, its members are alarmed to learn of the existence of a humanoid which has been made externally indistinguishable from a human and which has killed a man. They demand that all existing humanoids be disassembled or downgraded to a strictly utilitarian machine-like form.

Scientist Dr. Raven (Doolittle) has developed a technique called a "thalamic transplant", which transfers the memories and personality of a recently deceased human into a robotic replica of that person. The human-humanoid hybrids that result awake from the process unaware of their own transformation, although their human personalities are shut off between 4 and 5 A.M., when they report back to the humanoids at the robot temple. As Dr. Raven describes the operation, "We draw off everything that makes a man peculiar to himself. His learning, his memory: these, inter-reacting, constitute his personality, his philosophy, capability and attitude. The human brain is merely the vault in which the man is stored." With the help of Dr. Raven, the humanoids are secretly replacing humans who recently died with these replicas.

One of the leaders of the Order of Flesh and Blood, Captain Kenneth Cragis (Megowan), meets Maxine, and although she is opposed to the Order they both fall in love. In the end they discover that they, too, are advanced humanoid replicas with the minds of deceased persons. Ironically, the "real" Maxine had died in a bomb attack which the Order intended to harm only robots. Dr. Raven, a once-human replica himself, explains to Cragis and Maxine that not only are they practically immortal in their new forms they can also be the first humanoids upgraded to the highest possible level: after a minor alteration, they will be able to procreate.

Finally, Dr. Raven breaks the fourth wall, looks directly into the camera and tells the viewer, "Of course, the operation was a success ... or you wouldn't be here." This final line implies the story was set in the distant past.

Cast

- Don Megowan as Capt. Kenneth Cragis

- Erica Elliot as Maxine Megan

- Don Doolittle as Dr. Raven

- George Milan as Acto, a clicker

- Dudley Manlove as Lagan, a clicker

- Frances McCann as Esme Cragis Milos

- David Cross as Pax, a clicker

- Malcolm Smith as Court

- Richard Vath as Mark, a clicker

- Reid Hammond as Hart, Chairman of Surveillance Committee

- Pat Bradley as Dr. Moffitt

- William Hunter as Ward, Surveillance Committee Member

- Gil Frye as Orus, a clicker

- Alton Tabor as Kelly's Duplicate

- Paul Sheriff as Policeman

Production

The Creation of the Humanoids is normally dated to 1962, the year of its general release, but one screening in 1961 is documented by an advertising flyer and the film itself displays a 1960 copyright date (MCMLX in Roman numerals), indicating that it was a complete film before the end of that year. Short items in contemporary trade publications indicate that it was being filmed in the summer of 1960 under a working title variously reported as This Time Around or This Time Tomorrow.[2][3] The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences lists August 1960 as the completion date.[4] Producer-director, former child star and Hollywood area native Wesley Barry's Genie Productions was located in Hollywood,[5] and the cast and crew credits are populated by Hollywood personnel, but no information about the actual filming location and other specific details has yet come to light.

The film's limited budget is most apparent from its rudimentary sets, which consist mainly of a few blank flats, floor-to-ceiling drapes, or other simple elements set up in front of a painted background scene or a black void, as well as from its costumes, most of which are either generic jumpsuits or a uniform composed of stock costume rental items such as Confederate Army caps. Yet the producers opted for the added expense of filming in color at a time when black-and-white was still being used for many major-studio productions and was readily accepted by audiences, and they obtained the services of two top-tier behind-the-camera talents, albeit in the twilights of their careers.

Cinematographer Hal Mohr had a very extensive Hollywood career and two Academy Awards to his credit. Mohr used lighting and camera angles to make the best of the sets and add some visual interest to the long, actionless talking-head scenes that make up nearly all of the film. He sometimes used classic Hollywood "glamor lighting" techniques when photographing the normal-looking "human" characters, giving some scenes a degree of visual polish seldom seen in a low-budget exploitation film.

Jack Pierce was Universal Pictures' master makeup artist during all of the 1930s and most of the 1940s and created the iconic Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein makeups among many others. The most unusual features of Pierce's makeup design for this film are the large reflective scleral contact lenses that give the humanoids the appearance of having metal ball eyes. The lenses were furnished by Dr. Louis M. Zabner, an optometrist who pioneered the use of contact lenses to change actors' eye color and is credited in the film for "special eye effects". At that time, scleral lenses were made of a hard plastic. Wearing them was uncomfortable and they had to be removed frequently. Pierce had used similar silvery lenses in 1957 for brief close-ups in The Brain from Planet Arous. Most of the considerable time and effort it took to apply the rest of the humanoid makeup was spent on hiding the actors' hair, which it would have been unthinkable to expect them to actually shave off for a few days' work in a low-budget film. Latex rubber "bald wigs" were glued on, eyebrows were stuck down flat, then putty was carefully applied to cover rough textures and blend in tell-tale edges. Finally, the actors' heads were painted all over with blue-gray greasepaint and they were given rubber gloves of the same color.

The musical score consists of electronically generated sounds and wordless female vocalizing that suggests the Theremin music often used in science fiction films of the 1950s (e.g., The Day the Earth Stood Still and It Came from Outer Space). The credit appearing in the film is "Electronic Harmonics by I.F.M." The Internet Movie Database lists producer Edward J. Kay as the composer, though this information is nowhere verified.

Release

A general theatrical release through Emerson Film Enterprises was launched with an official opening in Los Angeles on 3 July 1962. An advertising campaign was begun, including the broadcast of short TV spots. Unlike most film posters of the time, which were printed by a four-color process that allowed a full range of eye-catching colors to be used, the posters for this film were two-color printings limited to black, white, red, grays, pinks and browns. The use of a two-color poster for a small independent black-and-white film was not uncommon, but it was unusual when one of the selling points of the film being advertised was the fact that it was in color.

Makeup artist Jack Pierce participated in the 1962 publicity campaign by giving interviews and by making up Los Angeles TV movie host Wayne Thomas as a humanoid, complete with silvery contact lenses, during a live broadcast. Progress in the application of the makeup was televised during commercial breaks in the unrelated film being shown. The live segments were temporarily saved on videotape and rebroadcast several times in the following days.

After running its theatrical course in drive-ins, low-end suburban theaters, "kiddie matinees" and urban theaters specializing in exploitation films, the film was released to television, where it was being shown by late 1964.[6] It was released on Beta and VHS videocassettes by Monterey Home Video in 1985 and was later available from Something Weird Video. The first licensed DVD release came in 2006 on a double-feature disc from Dark Sky Films.

The film's running time is often listed as 75 minutes.[7][8][9] The Dark Sky DVD release runs 84 minutes and is presented in anamorphic 16:9 widescreen, which approximates the matted aspect ratios most commonly used for 35 mm projection in the United States in 1962. The earlier videocassette releases are not pan-and-scan versions of a widescreen image, but simply unmatted full-frame 1.33:1, revealing areas at the top and bottom of the image not normally seen in a theater.

Reception

The film's theatrical run was apparently not commented on in the mainstream press. The public reception as measured by theater attendance and profitability is unclear, but one 1962 item in the trade paper Variety notes that "Creation of the Humanoids and Invasion of the Animal People at the Fox shape to a sock $10,000", "sock" being a favorable term in that publication's show-business jargon and $10,000 the week's box office receipts at the Fox theater.

After its 1964 television debut, references to more than its title began to appear. In 1965, Susan Sontag briefly mentioned some story details in her essay on science fiction films entitled The Imagination of Disaster.[10]

Later critical opinion

"Slow, stagy cheapie" – Leonard Maltin.[7]

"This interesting film...is badly let down by Simms' over-talkative script." – The Aurum Film Encyclopedia – Science Fiction.[8]

"Incredible little film" – Michael Weldon, The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film.[9]

"...a highly underrated gem of considerable worth [and] a perfect illustration of how science-fiction should work as a literature of ideas rather than of special effects." – Richard Scheib, Moria – The Science Fiction, Horror and Fantasy Film Review.[11]

"Yes, it is ham-handedly, painfully un-subtle, but making a film with this message in the early 1960s, with the storms of the civil rights movement still raging, required considerable courage on the part of the filmmakers." – Erick Harper, DVD Verdict.[12]

"Undeniably sophisticated as science fiction, The Creation of the Humanoids is one weird movie." – Glenn Erickson, DVD Savant.[13]

In popular culture

The Creation of the Humanoids is often said to be "Andy Warhol's favorite film".[14] The original source for this claim appears to be a 1964 art review of new Warhol paintings that begins with a short description of the film and states that the protagonists' climactic discovery is "the happy ending of what Andy Warhol calls the best movie he has ever seen."[15]

See also

References

- The opening credits read: "Story and screenplay by Jay Simms".

- American Cinematographer (1960) 41:570 (issue number and date not available but not earlier than 1 July as evident from mention of that date on page 442)

- Motion Picture Herald (1960) 220-221:56 (issue number and date not available but mid-year and before 8 September)

- Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences list of credits for The Creation of the Humanoids Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine (completion date shown as 08/60)

- The 1962 Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures, page 586

- Los Angeles Times, 15 November 1964, weekly TV Times insert, various pages (shown repeatedly on channel 9 as that week's so-called "Million Dollar Movie")

- Leonard Maltin's 2008 Movie Guide, Signet/New American Library, New York, 2007.

- Phil Hardy (ed.), The Aurum Film Encyclopedia – Science Fiction, Aurum Press, London, 1991.

- Michael Weldon: The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, Plexus, London 1989.

- Susan Sontag: The Imagination of Disaster, in Commentary magazine, October 1965, New York.

- Online review at Moria – The Science Fiction, Horror and Fantasy Film Review.

- Online review at DVD Verdict.

- Online review at DVD Savant.

- Fujiwara, Chris (2004-05-01). "Intonation Please: The Creation of the Humanoids" (PDF). In Rickman, Gregg (ed.). The Science Fiction Film Reader. Limelight. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-87910-994-3. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

No source, as far as I can determine, is known for this tidbit, but whether or not Warhol made such a statement is less important than what it means as a characterization of the film.

- Bourdon, David. Andy Warhol (art review). The Village Voice, 3 December 1964, page 11