The Fuentidueña Apse

The Fuentidueña Apse is a Romanesque apse dated 1175–1200 that was built as part of the San Martín Church at Fuentidueña, province of Segovia, Castile and León, Spain. Little is known about the church's commission, design or early history. It is believed to have been built when the town was of strategic importance to the Christian kings of Castile in their defence against Moorish invaders; the church is situated on an imposing hill below a fortified castle.

By the 19th century the church was long abandoned and in disrepair. In the late 1940s, the apse was moved and reconstructed in The Cloisters of New York City. This transfer involved the shipping of almost 3,300 blocks of stone from Spain to New York. The acquisition followed three decades of complex negotiation and diplomacy between the Spanish church and both countries' art historical hierarchies and governments. The apse was eventually exchanged in a complex deal that involved the gifting by New York of six frescoes from the San Baudelio de Berlanga to the Prado Museum, on an equally long term loan.[1]

Today the apse is situated in the Cloisters' Fuentidueña hall, the museum's largest room.[2]

Apse

The apse measures 919.5 × 749.3 × 843.3 cm. It consists of a broad arch leading to a barrel vault and culminating in a half dome.[3] The exterior wall holds three small windows,[1] narrow and stilted, but designed to let in as much light as possible. The windows were originally set within imposing fortress walls; according to the art historian Bonnie Young "these small windows and the massive, fortress-like walls contribute to the feeling of austerity that is typical of Romanesque churches."[3] The supporting piers show three large figures. Saint Martin of Tours (c. 316–397), patron saint of the church is on the left. On the right is the angel Gabriel, in the act of Annunciation to the Virgin. The capital above the Annunciation shows a scene from the Nativity.[4] Below the triumphal arch are two columns whose capitals depict scenes from the Adoration of the Magi on the left, and Daniel in the lions' den to the right.[5] The capitals of the blind arcades contain a variety of fantastical creatures. The moldings are carved in billet and floral patterns. The walls are lined by a number of niches, "oddly shaped" according to Young, but probably placed to rest liturgical implements for mass.[3]

The apse was built from over 3,300 individual stone blocks, mostly sandstone and limestone,[6] which were shipped to New York in 839 individual crates.[7] It was such a major and large installation into the Cloisters that it necessitated a complete refurbishment of the former "Special Exhibition Room". It was opening to the public in 1961, seven years after the transfer, its re-installation was a major and groundbreaking innovative undertaking. The new space seeks to emulate a single aisle nave.[8]

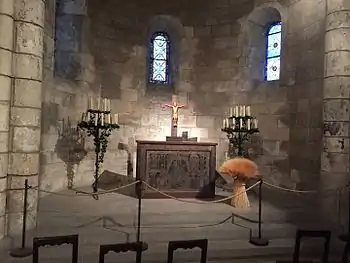

The capitals supporting the arch portray the Adoration of the Magi and Daniel in the lions' den. Its piers contain the figures of Saint Martin of Tours on the left and the angel Gabriel announcing to The Virgin on the right. The Fuentidueña room includes a number of other, mostly contemporary medieval art works set within the Fuentidueña Apse. They include, in its dome, a large fresco c. 1130–50, from the Spanish Church of Sant Joan de Tredòs, in its colorisation resembling a Byzantine mosaic and is dedicated to the ideal of Mary as the mother of God.[9] Hanging within the apse is a c. 1150–1200 crucifix from the convent of St. Clara at Astudillo.

Ancillary objects

The Fuentidueña apse contains a c 1150–1200 white oak, red paint, pine and gilding and monumental Crucifix hanging before it.[10] The cross is 178 cm high and 260 cm wide, and believed to originate from the convent of St Clara at Astudillo, near Palencia, in north-western Spain, though records are unclear and that is contested.[11] The cross seems designed to hang above an altarpiece. Its reverse contains a depiction of the Agnus Dei ("lamb of God"), decorated with red and blue foliage at its frames.

Acquisition

In the early 1930s, the philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had commissioned The Cloisters, financed the Metropolitan Museum of Art to acquire a number of Medieval architectural elements from Europe for incorporation into the building. Representatives were sent to Europe, mostly to France, to find an apse that might be suitable, with the current one from the San Martín Church, Fuentidueña identified in 1931, shortly after it had been declared a Spanish National Monument. However, both the Catholic church and the Spanish State claimed ownership of the building and site, and no agreement could be made for acquisition.[12]

There are no surviving records of its original construction. It was built in the mid 12th century, when the town was of strategic importance to the Kingdom of Castile, then defending against the Moors; it is situated on a hill, somewhat imposingly, and just below a castle, for which it probably served as its chapel.[3] The church was long abandoned and in ruin at the time, with only the apse remaining in relatively good condition. It was roofless, and as a result had suffering deterioration over the centuries. Its interior was at the time being used as a modern cemetery.[12] No illustrations of its interior existed until 1928, when the American art historian and medievalist Arthur Kingsley Porter reproduced two photographs of some of the sculptured figures in his "Spanish Romanesque Sculpture".[12]

The exchange was looked upon more favorably by the Spanish 12 years later, when again approached by the Metropolitan, who argued that the apse would be better conserved in a roofed building. During the negotiations, the Spanish were represented by Francisco Javier Sánchez Cantón (later director of the Prado), and the archaeologist and historian Manuel Gómez-Moreno Martínez. The Metropolitan assured the citizens of Fuentidueña by promising to pay for the reinforcement of the local parish church of San Miguel, and to rebuild its tower, which was then also in disrepair, and threatening to fall. After years of negotiation, diplomacy and wide consultation, including with the Council of Minister of Spanish Government, the Bishop of Segovia and the Fine arts Academy of San Fernando, in 1957 the Council of Ministers sanctioned the loan, on five conditions which obligated the Metropolitan to:

- Purchase six frescoes from the San Baudelio de Berlanga, to be loaned to the Prado. The frescoes included "two scenes from the chase, the bear, the elephant, the decorative panel with eagles, and the warrior with shield"

- Pay for the cataloging of all the "drawings and forms", and for taking down, packing and preparing for shipment of the stones

- Fund the reconstruction of the San Miguel church

- Fund the Ayuntamiento de Fuentidueña's upkeep of the cemetery, and other purposes

- Fund the shipment to New York, and its reconstruction there, including the placing of a roof over the apse, and the treatment of damaged stonework. The reconstruction was to be clearly displayed with a plaque indicating that it was on loan from the Spanish government[13]

See also

Notes

- Wixom, 36

- Rorimer, 267

- Young, 14

- "Apse from San Martín at Fuentidueña". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 May 2016

- Wixom, 38

- Barnet, 36

- "Monumental Moving Job". New York: Life Magazine, 20 Oct 1961.

- Barnet, 38

- Young, 17

- "Crucifix". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 May 2016

- Wixom, 39

- Rorimer, 265

- Rorimer, 266

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fuentidueña Chapel. |

- Barnet, Peter. The Cloisters: Medieval Art and Architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1-5883-9176-6

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Guide. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012. p 203

- Medieval monuments at the Cloisters as they were and as they are. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1972. ISBN 978-0-8709-9027-4

- Rorimer, James J. "The Apse from San Martin at Fuentidueña". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 19.10, 1961

- Young, Bonnie. A walk through the Cloisters. New York: Viking Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0-8709-9203-2

- Wixom, William. "Medieval Sculpture at The Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, volume 46, no. 3, Winter, 1988–1989

External links

- The Fuentidueña Apse: A Journey from Castile to New York, documentary, The Metropolitan Museum of Art