The Giant Joshua

The Giant Joshua is a 1941 novel written by Maurine Whipple about polygamy in nineteenth-century Utah Dixie. The idea for the novel started as a short story submitted to the Rocky Mountain Writer's conference in 1937. There Ferris Greenslet encouraged Whipple to apply for Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship, which she won in 1938 in advance of her first novel. With Greenslet's encouragement and support, she completed it over the course of three years.

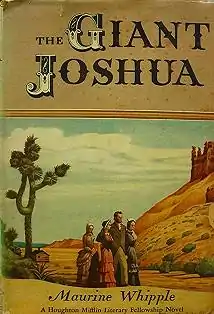

First edition (1941) | |

| Author | Maurine Whipple |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical Novel |

| Set in | Utah Dixie |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin, Doubleday, Western Epics |

Publication date | 1941 |

| Pages | 637 |

| ISBN | 0914740172 |

The novel focuses on the life of Clorinda (Clory), who becomes the third wife of Abijah MacIntyre and lives in Southern Utah during its early years of colonization by Mormon pioneers. Clory survives through both emotional and physical hardship as she experiences the deaths of her children and multiple miscarriages, near-starvation due to drought and floods, and emotional neglect from Abijah. One of the themes of the work is how polygamy and enduring harsh conditions are both tests of faith. Whipple embeds folk beliefs and narratives into her story, giving it greater depth.

Contemporary reviewers praised Whipple's realistic portrayal of Mormon pioneers in Utah and the way her realistic characters elicited sympathy. John A. Widtsoe, a prominent church leader, wrote that its treatment of polygamy was unfair, but that it showed the "epic value" of early settlements. After a resurgence in interest in Mormon literature in the 1970s and 1980s, the book became one of the best-known examples of a Mormon novel. Terryl Givens wrote that it is "perhaps the fullest cultural expression of the Mormon experience," and Eugene England stated it was the greatest Mormon novel. Though Whipple planned to write a sequel, she never finished one.

Plot

.jpg.webp)

Among the many real characters such as Brigham Young, John D. Lee, and Erastus Snow, The Giant Joshua focuses primarily on Abijah MacIntyre and his wives, Bathsheba, Willie, and Clorinda (Clory), who move to southern Utah in 1861, and become prominent members of the communities of Washington, Santa Clara, and St. George during their founding years. The book focuses on Clory's life, starting with her as a 17-year-old third bride to the forty-year-old Abijah. Abijah unexpectedly consummates their marriage and Clory becomes disillusioned with wifely obedience. Abijah's teenage son, Freeborn, comforts Clory and Abijah brings the two to Erastus Snow, who rebukes them all. Later, Clory is pregnant and determined to leave St. George, but stays after seeing the natural beauty of a large group of Sego Lilies. Drought and heavy rains wreak havoc on the town, and the harvest is poor. Clory gives birth to a daughter nicknamed Kissy, and John D. Lee is ignored by his neighbors after the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Freeborn is killed by Indians, and Clory becomes depressed and has a miscarriage. Abijah blesses Kissy after she falls out of a wagon in an accident, and Clory feels love for him.

Clory has two more children, Abijah leaves on a mission to England, and all three of Clory's children die in the aftermath of a plague of grasshoppers. Abijah blames Clory, and she learns glovemaking to earn money. When Abijah returns from his mission, he gives her a house and she gives birth to a son, Jim. Abijah's second wife, Willie, dies in childbirth after he refuses to send for a doctor. Clory takes organ lessons from one of Brigham Young's wives, who also teaches her how to raise silk worms. Clory feels contentment with her position in life. The discovery of silver nearby brings miners to the town, which brings new challenges. Brigham Young dies and church leaders are arrested for practicing polygamy. Clory's hands are covered in sores from working with leather in her glovemaking work, and she keeps them bandaged. Abijah is called as the president of the Logan temple, takes a new, young wife and leaves his other wives behind. Erastus Snow dreams of using a spillway instead of dams to cope with St. George's flooding problems. Clory has a final miscarriage after she is frightened by a dog. On her deathbed, Clory realizes that she had a testimony of the truthfulness of her religion all along.

Themes

Mormon scholar Terryl Givens notes that the book presents plural marriage as a "marathon Abrahamic test" of faith similar to colonizing Utah's desert.[1] Polygamy is more than an unusual set of sexual partners; it is the setting of emotional and spiritual sacrifice. Whipple also shows how isolated Clory was when she notes Clory's excitement to see a non-Mormon, or "Gentile." Whipple focuses on the actions of pioneers, not their beliefs. The way Mormons build up Zion by colonizing the desert mirrors a figurative building of the church as Zion.[1]

Folklorist William A. Wilson praised the way Whipple used folklore in context in a way that elicited sympathy and understanding of folk beliefs. He praised Whipple's portrayal of a Mormon experience, noting how she used folk narratives as plot elements, which paralleled the way faith-promoting events occurred and failed to occur. Clory herself vacillates between faith and disbelief. Wilson felt that the book's last 200 pages failed, which he attributed to their lack of concrete references to folklore.[2]

Background

.jpg.webp)

Whipple's "Beaver Dam Wash" was submitted to the 1937 Rocky Mountain Writer's Conference.[3]:103–104 At the conference, Ford Maddox Ford liked "Beaver Dam Wash" and convinced Ferris Greenslet, then vice president at Houghton Mifflin, to read it. Greenslet advised Whipple to make the novella a little longer; instead, she proposed a Mormon epic and sent a sample chapter. Greenslet encouraged her to apply for Houghton Mifflin's $1,000 literary fellowship for new writers working on their first novel.[3]:105; 110–111 Whipple lived with her parents while she wrote the chapters for the fellowship application, often getting inspiration right before falling asleep and working through the night. Greenslet helped her to apply for the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship, which she won in 1938 .[4][3]:111–112 Greenslet greatly encouraged her while she wrote The Giant Joshua over the next three years. He constantly gave her advice, personally lent her money, and made it possible for her to stay at the artist colony Yaddo to finish writing the book.[5] Whipple disliked Yaddo, complaining that she felt lonely and isolated, and completed much writing there.[6] Joseph Walker, an ex-Mormon doctor from St. George living in Hollywood, read early manuscripts and wrote Whipple encouraging letters.[3]:161–163 She wrote the manuscript in longhand and had others type it up for her.[5]

After its publication in 1941, The Giant Joshua was not very profitable to Whipple. As a fellowship winner, the accompanying contract was not generous, and Whipple had received advances on her royalty checks to finish the novel.[5] Whipple also hired a literary agent, Maxim Liber, just after the publication of The Giant Joshua, and Liber took a percentage of money due to her. She fired him that August.[3]:194;211 Historian Juanita Brooks helped Whipple with historical details in The Giant Joshua, though Brooks was disappointed at the historical inaccuracies Whipple kept in the novel. Whipple was also inspired by her own family history and family stories from the Beckstrom family and Annie Atkin, who grew up in St. George and later married Vasco Tanner.[3]:132–133

A paperback edition was issued in 1964.[7] It is not known when this edition by Doubleday went out of print.[3]:386 Whipple renewed the copyright in 1969 for twenty-eight years.[3]:400 Whipple asked two different publishers to reprint the book in 1974, but both declined.[3]:386 In 1976, Sam Weller, a prominent bookseller in Salt Lake City, reprinted it in hardback under his Western Epics imprint,[3]:386 where it went through several printings.[8]

Reception

The Giant Joshua sold well. It was fifth in a list of ten in Harper's Poll of the Critics and was second in The Denver Post's list of bestsellers.[4] The novel had fans who sent Whipple letters expressing their love for her epic novel.[1][3]:183 The U.S. Navy bought 200 copies for ship libraries.[9] Writing in the Book-of-the-Month-Club Bulletin, Avis DeVoto praised the way Whipple used historical details about clothing and food in the book, which made her characters "bursting with vitality."[3]:180 Ray B. West in the Saturday Review of Literature wrote that the book showed the "tenderness and sympathy" between early Mormons.[6] A review in Time stated that it was "competent but never quite excellent."[10] John Selby's review, which appeared in multiple newspapers, described the characters as "real people, whose beliefs seal them up, as it were, in a kind of transparent separateness in which [they] seem oddly luminous."[11][12][13]

Edith Walton at The New York Times wrote that Whipple's writing was not anti-Mormon, but "scrupulously fair and even sympathetic," adding that though the book was "maybe a little over-long," it was "rich, robust and oddly exciting."[14] A review appearing in The Coschocton Tribute predicted that Mormons would not like the book, which showed an "intimate side of earlyday Mormon life."[15] Indeed, The Giant Joshua did not have the endorsement of any LDS Church leader. John A. Widtsoe, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, wrote in The Improvement Era that its treatment of polygamy was unfair,[1] though he praised how it showed the "epic value" of Mormon settlements.[6] In a private letter, Emma Ray McKay said she was "so disgusted with the author of The Giant Joshua that I can scarcely contain myself."[16] Whipple's father intercepted her advance copy and told her it was "vulgar" while other residents of St. George had mixed feelings about how their ancestors' stories were included or excluded.[3]:181 Not all Utah residents disliked the book; friends and acquaintances wrote her letters of congratulations and praise.[3]:182

In the 1970s, with the growth of Mormons arts and criticism, The Giant Joshua enjoyed a resurgence in attention from scholars.[2] Writing for Sunstone in 1978, Bruce Jorgenson, a creative writing teacher at Brigham Young University, praised the "complicated" characters and strong portrayal of historical figures, with the exception of Erastus Snow. He critiqued the undisciplined narrative style, which he described as often succumbing to "ballooning clichés typical of the slick popular idiom of the thirties and forties."[17] Later reception of the book was even more positive.[4] In 1989, The Giant Joshua was the most-borrowed book in the Salt Lake City Public Library.[1] In "Fifty Important Mormon Books", Curt Bench reported that Mormon scholars in 1990 unanimously chose The Giant Joshua as the best Mormon novel before 1980.[18] In People of Paradox, Terryl Givens wrote that it is "perhaps the fullest cultural expression of the Mormon experience".[1] Eugene England described The Giant Joshua as "not the great Mormon novel, but the greatest."[17] The novel is well-known among Mormon religious faculty. In a 2002 survey, a group of mostly Mormon religious educators were asked to list the three most important books about Mormonism by LDS authors in several categories, including fiction. The Giant Joshua was the second-most popular item respondents listed under fiction (after The Work and the Glory series), although forty percent of respondents did not answer this question.[19]

Shortly before her death, Whipple was honored with a lifetime achievement award from the Association for Mormon Letters and which added substance to her longheld belief that Mormons would eventually recognize the worth of her work.[6][20]

Trilogy and derivative works

Whipple planned to write a sequel to The Giant Joshua, at times also imagining a trilogy. In fall 1945, Whipple signed a contract with Simon and Schuster to publish the sequel, to be titled Cleave the Wood. The agreement included an allowance of $150 a month for a year. Whipple wrote five chapters, which are found in her papers, but was not able to complete the novel.

According to Whipple, she worked with Gene Pack to arrange The Giant Joshua into a radio drama with 30-minute episodes. Gene Pack read the episodes five days a week during August and September in 1965. The owner of the KUER radio station, Ellen Winkelmann, allowed Pack and Whipple to tape the segments, but later kept and sold the tapes to a third party, much to Whipple's displeasure.[3]:374

In 1983, Whipple sold the movie rights to the book, which provided for her in her old age.[4] Sterling Van Wagenen, cofounder of the Sundance Film Festival, often spoke of his desire to adapt The Giant Joshua to film.[21]

References

- Givens, Terryl C. (2007). People of paradox : a history of Mormon culture. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 288–291. ISBN 0195167112.

- Wilson, William A. (October 7, 1978). "Folklore in The Giant Joshua". Third Annual Symposium of The Association for Mormon Letters. Marriott Library, University of Utah: The Association for Mormon Letters. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012.

- Hale, Veda Tebbs (2011), Swell suffering: a biography of Maurine Whipple, Salt Lake City, Utah: Greg Kofford Books, ISBN 9781589581241

- Hale, Veda Tebbs (August 1992), "In Memoriam Maureen Whipple" (PDF), Sunstone: 13–15

- Hale, Veda Tebbs (2008), Juanita Brooks Lecture Series: Maurine Whipple and her Joshua (PDF), St. George, Utah: Dixie State College of Utah, pp. 14–15

- Embry, Jessie (1994). "Maurine Whipple: The Quiet Dissenter". In Launius, Roger D.; Thatcher, Linda (eds.). Differing visions: dissenters in Mormon history. Urbana [u.a.]: Univ. of Illinois Press. pp. 305–306. ISBN 9780252020698.

- "For the first time! In a paperback edition". The Salt Lake Tribune. 1964-03-09. p. 8. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

- Weller, Sam. "Samuel Weller, Salt Lake City, Utah: an interview by Everett L. Cooley". collections.lib.utah.edu. J. Willard Marriott Library. p. 73. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "Writers of the Mountain West". Tucson Daily Citizen. 1942-01-28. p. 6. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

- "Mormon Wife". Time. 37 (1): 61. 1941-01-06. ISSN 0040-781X.

- Selby, John (1941-01-07). "Literary Guide". The Kingston Daily Freeman. p. 4. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

- Selby, John (1941-01-05). "The Literary Guidepost". The Sandusky Register. p. 4. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

- Selby, John (1941-01-03). "Today's 'Literary Guidepost'". The Morning Herald. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

- Walton, Edith H. (1941-01-12). ""The Giant Joshua" and Other New Works of Fiction". The New York Times. p. 6.

- "Early Mormon Life, Wife's Soul, Bared in 'Giant Joshua'". The Coshocton Tribune. 1941-01-03. p. 8. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

- Jepson, Theric. "Too sacred for public consumption -or- Disgusting the prophet’s wife", A Motley Vision. July 9, 2009. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- Jorgenson, Bruce (September 1978). "Retrospection: Giant Joshua" (PDF). Sunstone. 3 (6): 6–8. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- Bench, Curt (October 1990). "Fifty Important Mormon Books" (PDF). Sunstone.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garr, Arnold K. (2002). "Which Are the Most Important Mormon Books?". BYU Studies. 41 (3): 35–47. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- Association for Mormon Letters awards database Accessed 6 Feb 2016. The citation for the award read: "Maurine Whipple, native of St. George, is the author of This Is the Place: Utah and a host of articles and short stories in Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, Look, Life, Time, and Pageant. She is especially esteemed for her prize-winning novel The Giant Joshua, considered by many to be the finest work or Mormon fiction."

- "LDS FILMMAKER DREAMS OF `GIANT JOSHUA'". DeseretNews.com. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 27 February 2013.