The Snake and the Farmer

The Snake and the Farmer is a fable attributed to Aesop, of which there are ancient variants and several more from both Europe and India dating from Mediaeval times. The story is classed as Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 285D, and its theme is that a broken friendship cannot be mended.[1] While this fable does admit the possibility of a mutually beneficial relationship between man and snake, the similarly titled The Farmer and the Viper denies it.

Versions of the fable

The oldest Greek versions of the fable are numbered 51 in the Perry Index.[2] A snake dwells in a hole at the farmer's threshold and is tolerated until his son accidentally steps on it and is bitten and killed. The enraged father then chases the snake with an axe and cuts off its tail. When he later attempts to make his peace with the snake, it refuses on the grounds that neither of them will ever forget their mutual injuries. Substantially the same story appears in the Neo-Latin poems by Hieronymus Osius[3] and Pantaleon Candidus.[4]

However, an alternative version of the story is found in Mediaeval European sources that is separately numbered 573 in the Perry Index.[5] Here the snake feeds on food left by the man, or the left-overs from his table; it brings luck to the man, and as a consequence the man grows rich. Eventually he decides to kill the snake before it withdraw its favours, but the snake survives the attack and kills the man's son in revenge. The man then sues for peace but the snake replies that neither can forgive the other while evidences of former grievances remain.

In Marie de France's verse account at the close of the 12th century, the snake asks the farmer for a daily ration of milk and promises him enrichment. He is later persuaded by his wife to kill it and waits by its hole with an axe but only cleaves the stone at its entrance. The snake kills the man's sheep in revenge and when he asks for pardon tells him that he can no longer be trusted. The scar in the rock will always be a reminder of his bad faith. The moral on which Marie ends is never to take a woman's advice.[6] The broad outlines remain the same in the story that appears in the Gesta Romanorum a century later. A knight in debt makes a bargain with a serpent and is similarly enriched. When he is persuaded to treachery by his wife, the serpent kills his child and he is reduced to poverty. It is interpreted there as an allegory of sin and false repentance.[7]

These latter versions may have been influenced by the similar story that was also added to the Indian Panchatantra at the end of the 12th century. A farmer sees a snake emerge from a mound in his field and brings it food as an offering. In return it leaves a gold coin in the bowl. In a development reminiscent of the Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs, the man's son believes he will find a treasure horde in the snake's mound and tries to kill it, but loses his life instead. When the man comes to apologise, the snake rejects his peace making and declares that he is only motivated by greed.[8]

Joseph Jacobs has argued that the Indian source is the original and influenced all other versions, including those of antiquity, on the grounds that it is more comprehensive and explains points that are obscure in them.[9] Later research has shown that there is no Sanskrit version of the story earlier than 1199 CE, when it first appears in Purnabhadra's recension (III/6). On this account and others, therefore, Francisco Rodríguez Adrados proposes that, on the contrary, the Indian version has been influenced by the Greek.[10] He has, however, to theorise that some less fragmentary original, as yet undiscovered, underlies all the others and he does not explain how these variations came about.

References

- Ashliman site

- Aesopica site

- Fable 26

- Fable 21

- Aesopica site

- Die Fabeln der Marie de France, Halle 1898, Fable 72, pp.236-43

- University of Michigan

- Indian Fairy Stories, edited by Joseph Jacobs, London 1892, pp.112-14

- Indian Fairy Stories, pp.246-7

- History of the Graeco-Latin Fable vol.2, Leiden NL 2000, pp.107-09

External links

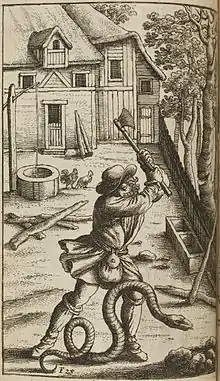

- Illustrations from books between the 16th - 19th centuries