Thomas the Archdeacon

Thomas the Archdeacon (Latin: Thomas Archidiaconus; Italian: Tommaso Arcidiacono; Croatian: Toma Arhiđakon; c. 1200 – 8 May 1268), also known as Thomas of Split (Latin: Thomas Spalatensis, Hungarian: Spalatói Tamás), was a Roman Catholic cleric, historian and chronicler from Split. He is often referred to as one of the greatest sources in the historiography of Croatian lands.[1]

Life

What is known about Thomas' life comes from his work, Historia Salonitana. He speaks of his life in the third person and very briefly, in the style of medieval literature genres. Thomas was born in Split at the beginning of the 13th century. It is not known whether he was of noble or common birth, but he represented the elite Roman culture that had survived from before the Slav migration, and he had a negative view of Slavs, often mistakenly conflating them in his chronicle with the Goths.[2] He was probably educated at the cathedral school in Split. Around 1222 he was sent to study at the University of Bologna. There he perfected skills (under, among others, Accursius) in law, rhetoric, gramathic and notary (ars dictandi and ars notaria).[3] He saw Saint Francis of Assisi in Bologna, a remarkable event which he mentioned in his work, describing the person of Saint Francis.[4] Upon returning to his hometown of Split he advanced fast in church hierarchy. He became notary official (ca. 1227), then (1230) the archdeacon (head of the body of canons). He described Mongol siege of Split of 1242, Mongol customs and homeland, thus creating the first ethnological writings in local historiography.[5] In 1243 a body of canons chose Thomas to be archbishop of Split, however due to his views on Church autonomy in Split, commoners rebelled against him. Fearing for his life, he never occupied that function, and in the end resigned the honor. Because of that, in his work he wrote about future archbishops with bitterness. He died in Split on May 8, 1268. Today, his grave lies in the Church of St. Francis.[6]

Views

Thomas was a stern advocate of medieval commune movement in Split. He wrote about Croatian nobles (and Hungarian kings in his time) in the hinterland of the city with great animosity, because they tried to crush the autonomy of the city. And conversely, he treated fairly those who respected the commune autonomy (Croatian kings, and later, Hungarian kings in the 12th century). In 1239 he organized new („latin“) administration in Split, bringing Gargane de Ascindis from Ancona, as the new Podestà.[7] He was also an advocate of Church autonomy within the city (in accordance with official Roman Church teaching) which excluded commoners and citizens from interfering in Church business (such as the election of the archbishop).

Work

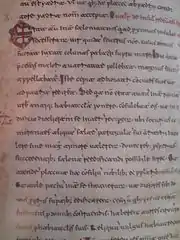

Thomas' only work is the Historia Salonitana, the history of the archbishops of Salona and Split written in Latin.[8] The work itself is combining three medieval history genres – historia, chronica and memoriale. Eventually, his work outgrows the narrow theme of archbishops, and becomes an outstanding literary achievement which encompasses the whole of the Croatian medieval period up to the 13th century. Because of Thomas' original research in the archbisphoric's archive in Split, he brings facts and news from documents today unknown to contemporary historians. His work is therefore not only of great literally value, but also of historical value for Croatian history.[9]

References

- Radoslav Katičić: "Toma Arhiđakon i njegovo djelo" in Toma Arhiđakon: Historia Salonitana, Split, 2007.

- Fine (Jr), John V. A. (2006). When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Katičić: "Toma Arhiđakon i njegovo djelo", 2007, p. 338.

- Eodem anno in die assumptionis dei genitricis, cum essem Bononie in studio, uidi sanctum Franciscum predicantem in platea ante palatium publicum, ubi tota pene civitas convenerat. Fuit autem exordium sermonis eius: angeli, homines, demones. De his enim tribus spiritibus rationalibus ita bene et discrete proposuit, ut multis litteratis, qui aderant, fieret admirationi non modice sermo hominis ydiote; nec tamen ipse modum predicantis tenuit, sed quasi concionantis. Tota uero uerborum eius discurrebat materies ad extinguendas inimicitias et ad pacis federa reformanda. Sordidus erat habitus, persona contemtibilis, et facies indecora. Sed tantum deus uerbis illius contulit efficatiam, ut multe tribus nobilium, inter quas antiquarum inimicitarium furor immanis multa sanguinis effusione fuerat debachatus, ad pacis consilium reducenteretur. Erga ipsum uero tam magna erat reuerentia hominum et deutio, ut uiri et mulieres in eum cateruatim ruerent, satagentes vel fimbriam eius tangere , aut aliquid de paniculis eius auferre. Historia Salonitana, p. 134.

- James Ross Sweeney: "Thomas of Spalato and the Mongols: a Thirteenth Century Dalmatian Views of Mongol Customs." Florilegium 4 (1982): 156 – 183.

- On his tombstone are engraved the following words: Doctrinam, Christe, docet archidiaconus iste; Thomas, hanc tenuit, moribus et docuit; Mundum sperne, fuge viciu(m), carnem preme, luge; pro vite fruge, lubrica lucra fuge. Spalatemque dedit ortu(m), quo vita recedit. Dum mors succedit vite, mea gl(ori)a cedit. Hic me vermis edit, sic iuri mortis obedit; corpus quod ledit , a(n)i(m)amque qui sibi credit. A. D. MCCLXVIII. mense madii octavo die intrante. Tomislav Raukar: Hrvatsko srednjovjekovlje Zagreb, 2007.

- Katičić: "Toma arhiđakon i njegovo djelo", 2007.

- The work is available in several translations (Croatian, Russian etc.) The English translation is available from 2006: Thomae Archidiaconi Spalatensis / Archdeacon Thomas of Split, Historia Salonitanorum atque Spalatinorum pontificum / History of the bishops of Salona and Split. Latin text by Olga Perić, edited, translated and annotated by Damir Karbić, Mirjana Matijević-Sokol and James Ross Sweeney. Budapest; New York: Central European University Press, 2006, (Central European medieval texts, vol. 4).

- See Franjo Rački: Ocjena starijih izvora za hrvatsku i srbsku poviest srednjega vieka" Književnik I (1864) 358 – 388. and Stéphane Gioanni, The bishops of Salona (2nd–7th century) in the Historia Salonitana by Thomas the Archdeacon (13th century) : history and hagiography, in Écrire l’histoire des évêques et des papes, Fr. Bougard and M. Sot (edd.), Brepols, 2009, pp. 243–263