Trieste (bathyscaphe)

Trieste is a Swiss-designed, Italian-built deep-diving research bathyscaphe which reached a record depth of about 10,911 metres (35,797 ft) in the Challenger Deep of the Mariana Trench near Guam in the Pacific. On 23 January 1960, Jacques Piccard (son of the boat's designer Auguste Piccard) and US Navy Lieutenant Don Walsh achieved the goal of Project Nekton. It was the first manned vessel to reach the bottom of the Challenger Deep.[1]

Trieste shortly after her purchase by the US Navy in 1958 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Trieste |

| Builder: | Acciaierie Terni/Cantieri Riuniti dell'Adriatico |

| Launched: | 26 August 1953 |

| Fate: | Sold to the United States Navy, 1958 |

| Name: | Trieste |

| Acquired: | 1958 |

| Decommissioned: | 1966 |

| Reclassified: | DSV-0, 1 June 1971 |

| Fate: | Preserved as an exhibit in the U.S. Navy Museum |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Bathyscaphe |

| Displacement: | 50 long tons (51 Mg) |

| Length: | 59 ft 6 in (18.14 m) |

| Beam: | 11 ft 6 in (3.51 m) |

| Draft: | 18 ft 6 in (5.64 m) |

| Complement: | Two |

Design

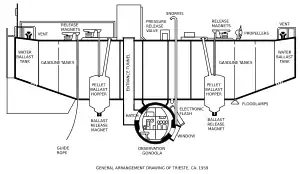

Trieste consisted of a float chamber filled with gasoline (petrol) for buoyancy, with a separate pressure sphere to hold the crew.[2] This configuration (dubbed a "bathyscaphe" by the Piccards), allowed for a free dive, rather than the previous bathysphere designs in which a sphere was lowered to depth and raised again to the surface by a cable attached to a ship.

Trieste was designed by the Swiss scientist Auguste Piccard and originally built in Italy. His pressure sphere, composed of two sections, was built by the company Acciaierie Terni. The upper part was manufactured by the company Cantieri Riuniti dell'Adriatico, in the Free Territory of Trieste (on the border between Italy and Yugoslavia, now in Italy); hence the name chosen for the bathyscaphe. The installation of the pressure sphere was done in the Cantiere navale di Castellammare di Stabia, near Naples. Trieste was launched on 26 August 1953 into the Mediterranean Sea near the Isle of Capri. The design was based on previous experience with the bathyscaphe FNRS-2. Trieste was operated by the French Navy. After several years of operation in the Mediterranean Sea, the Trieste was purchased by the United States Navy in 1958 for $250,000 (equivalent to $2.2 million today).

At the time of Project Nekton, Trieste was more than 15 m (50 ft) long. The majority of this was a series of floats filled with 85,000 litres (22,000 US gal) of gasoline, and water ballast tanks were included at either end of the vessel, as well as releasable iron ballast in two conical hoppers along the bottom, fore and aft of the crew sphere. The crew occupied the 2.16 m (7.09 ft) pressure sphere, attached to the underside of the float and accessed from the deck of the vessel by a vertical shaft that penetrated the float and continued down to the sphere hatch.

The pressure sphere provided just enough room for two people. It provided completely independent life support, with a closed-circuit rebreather system similar to that used in modern spacecraft and spacesuits: oxygen was provided from pressure cylinders, and carbon dioxide was scrubbed from breathing air by being passed through canisters of soda-lime. Power was provided by batteries.

Trieste was subsequently fitted with a new pressure sphere,[3] manufactured by the Krupp Steel Works of Essen, Germany, in three finely-machined sections (an equatorial ring and two caps).

To withstand the enormous pressure of 1.25 metric tons per cm2 (110 MPa) at the bottom of Challenger Deep, the sphere's walls were 12.7 centimetres (5.0 in) thick (it was overdesigned to withstand considerably more than the rated pressure). The sphere weighed 14.25 metric tons (31,400 pounds) in air and eight metric tons (18,000 pounds) in water (giving it an average specific gravity of 13/(13−8) = 2.6 times that of sea water). The float was necessary because of the sphere's density: it was not possible to design a sphere large enough to hold a person that could withstand the necessary pressures, yet also have metal walls thin enough for the sphere to be neutrally buoyant. Gasoline was chosen as the float fluid because it is less dense than water, and also less compressible, thus retaining its buoyant properties and negating the need for thick, heavy walls for the float chamber.

Observation of the sea outside the craft was conducted directly by eye, via a single, very tapered, cone-shaped block of acrylic glass (Plexiglas), the only transparent substance identified which would withstand the external pressure. Outside illumination for the craft was provided by quartz arc-light bulbs, which proved to be able to withstand the over 1,000 standard atmospheres (15,000 pounds per square inch) (100 MPa) of pressure without any modification.

Nine metric tons (20,000 pounds) of magnetic iron pellets were placed on the craft as ballast, both to speed the descent and allow ascent, since the extreme water pressures would not have permitted compressed air ballast-expulsion tanks to be used at great depths. This additional weight was held in place at the throats of two hopper-like ballast silos by electromagnets, so in case of an electrical failure the bathyscaphe would automatically rise to the surface.

Transported to the Naval Electronics Laboratory's facility in San Diego, California, Trieste was modified extensively by the Americans, and then used in a series of deep-submergence tests in the Pacific Ocean during the next few years, culminating in the dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep during January 1960.[2]

_over_the_Marianas_Trench%252C_23_January_1960_(NH_96797).jpg.webp)

The Mariana Trench dives

Trieste departed San Diego on 5 October 1959 for Guam aboard the freighter Santa Maria to participate in Project Nekton, a series of very deep dives in the Mariana Trench.

On 23 January 1960, she reached the ocean floor in the Challenger Deep (the deepest southern part of the Mariana Trench), carrying Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh.[4] This was the first time a vessel, manned or unmanned, had reached the deepest known point of the Earth's oceans. The onboard systems indicated a depth of 11,521 metres (37,799 ft), although this was revised later to 10,916 metres (35,814 ft); fairly recently, more accurate measurements have found Challenger Deep to be between 10,911 metres (35,797 ft) and 10,994 metres (36,070 ft) deep.[5]

The descent to the ocean floor took 4 hours 47 minutes at a descent rate of 0.9 metres per second (3.2 km/h; 2.0 mph).[6][7] After passing 9,000 metres (30,000 ft), one of the outer Plexiglas window panes cracked, shaking the entire vessel.[8] The two men spent twenty minutes on the ocean floor. The temperature in the cabin was 7 °C (45 °F) at the time. While at maximum depth, Piccard and Walsh unexpectedly regained the ability to communicate with the support ship, USS Wandank (ATA-204), using a sonar/hydrophone voice communications system.[9] At a speed of almost 1.6 km/s (1 mi/s) – about five times the speed of sound in air – it took about seven seconds for a voice message to travel from the craft to the support ship and another seven seconds for answers to return.

While at the bottom, Piccard and Walsh reported observing a number of small sole and flounder (both flatfish).[10][11] The accuracy of this observation has later been questioned and recent authorities do not recognize it as valid. The theoretical maximum depth for fish is at about 8,000–8,500 m (26,200–27,900 ft), beyond which they would become hyperosmotic.[12][13][14] Invertebrates such as sea cucumbers, some of which potentially could be mistaken for flatfish, have been confirmed at depths of 10,000 m (33,000 ft) and more.[12][15] Walsh later said that their original observation could be mistaken as their knowledge of biology was limited.[13] Piccard and Walsh noted that the floor of the Challenger Deep consisted of "diatomaceous ooze". The ascent took 3 hours and 15 minutes.

Other deep dives by Trieste

Beginning in April 1963, Trieste was modified and used in the Atlantic Ocean to search for the missing nuclear submarine USS Thresher (SSN-593). Trieste was delivered to Boston Harbor by USS Point Defiance (LSD-31) under the command of Captain H. H. Haisten. In August 1963, Trieste found the wreck off the coast of New England, 2,600 m (8,400 ft) below the surface.[16] Trieste was changed, improved and redesigned so many times that almost no original parts remain. It was transported to the Washington Navy Yard where it was exhibited along with the Krupp pressure sphere in the National Museum of the U.S. Navy at the Washington Navy Yard in 1980. Its original Terni pressure sphere was incorporated into the Trieste II.

Awards

- Navy Unit Citation with star

- Meritorious Unit Commendation with star

- Navy E Ribbon

- National Defense Service Medal with star

See also

References

- "First Trip to the Deepest Part of the Ocean The Bathyscaphe Trieste carried two hydronauts to the Challenger Deep in 1960". Geology.com. 2005-2015 Geology.com. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Trieste Bathyscaphe". Machine-History.Com. from Time article 12 October 1953. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Bathyscaphe" (PDF). National Geographic Education. 2015 National Geographic Society. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Trieste".

- Amos, Jonathan (7 December 2011). "Oceans' deepest depth re-measured". BBC News. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- NGC: On the sea floor

- To the Depths in Trieste, University of Delaware College of Marine Studies

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), Rolex Deep Sea Special, Written January 2006.

- "Wandank (ATA-204)". historycentral.com. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- Meet the only man alive who has been to the deepest ocean. BBC. 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- "Meet the creatures that live beyond the abyss". BBC. 22 January 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- Wolff, T. (1961). "The deepest recorded fishes". Nature. 190: 283–284. doi:10.1038/190283a0.

- Jamieson, A.J.; P.H. Yancey (2012). "On the Validity of the Trieste Flatfish: Dispelling the Myth". The Biological Bulletin. 222 (3): 171–175. doi:10.1086/BBLv222n3p171. PMID 22815365.

- Yanceya, P.H.; E.M. Gerringera; J.C. Drazen; A.A. Rowden; A. Jamieson (2014). "Marine fish may be biochemically constrained from inhabiting the deepest ocean depths". PNAS. 111 (12): 4461–4465. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322003111. PMC 3970477. PMID 24591588.

- Jamieson, A. (2015). The Hadal Zone: Life in the Deepest Oceans. Cambridge University Press. pp. 285–318. ISBN 978-1-107-01674-3.

- Brand, V (1977). "Submersibles - Manned and Unmanned". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 7 (3). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

Further reading

- Piccard, Jacques and Dietz, Robert S. (1961). Seven Miles Down; The Story of the Bathyscaph Trieste. G. T. Putnam's Sons.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trieste (submarine, 1953). |

- The Bathyscaph Trieste Celebrates the 50th Anniversary of the World's Deepest Dive

- Dives of the Bathyscaph Trieste - dictabelt recordings (pdf, page 38)

- 50th anniversary recollection by retired Navy Captain Don Walsh.

- 2008 obituary of diver Jaques Piccard

- Trieste Program Dive Log from the Collection of the Naval Undersea Museum

- The Bathyscaph Trieste Technical and Operational Aspects, 1958-1961 by LT Don Walsh, US Navy Electronics Laboratory