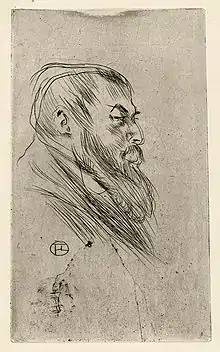

Tristan Bernard

Tristan Bernard (7 September 1866 – 7 December 1947)[1] was a French playwright, novelist, journalist and lawyer.

Life

Born Paul Bernard into a Jewish family in Besançon, Doubs, Franche-Comté, France, he was the son of an architect. He left Besançon at the age of 14 years, relocating with his father to Paris, where he studied at the Lycée Condorcet, which was noted for its numerous literary alumni. In 1888 was born his son Jean-Jacques Bernard, also a dramatist.

He studied law, but after his military service he started his career as the manager of an aluminium smelter. In the 1890s he also managed the Vélodrome de la Seine at Levallois-Perret and the Vélodrome Buffalo, whose events were an integral part of Parisian life, being regularly attended by personalities such as Toulouse-Lautrec.[2] He reputedly introduced the bell to signify the last lap of a race.[3]

After his first publication in La Revue Blanche in 1891, he became increasingly a writer and adopted the pseudonym Tristan. His first play, Les Pieds Nickelés (Nickel-plated Feet), was a great success and was representative of the style of his later work (generally humorous). He became known especially for his writing for vaudeville-type performances, which were very popular in France during that time. He also wrote several novels and some poetry. Bernard is remembered mainly for witticisms, particularly from his play Les Jumeaux de Brighton (The Brighton Twins). In 1932, he was a candidate for the Académie Française, but was not elected, receiving only 2 votes of a total of 39.

Drancy

He was interned during World War II at the Drancy deportation camp. When Gestapo agents were at his door he turned to his wife, who was crying, and said "Don´t cry, we were living in fear, but from now on we will live in hope". Public protest of his imprisonment caused his release in 1943. He died in Paris four years later, allegedly of the results of his internment, and was buried in Passy cemetery.

Legacy

A theater in Paris that he ran briefly as the "Théâtre Tristan-Bernard" in 1931 was later given the name permanently to honor him.

His descendants have achieved some fame. His son Raymond Bernard became an influential French filmmaker (using as scripts a number of works authored by his father) while his son Jean-Jacques Bernard published a memoir of his father in 1955 titled Mon père Tristan Bernard (My Father, Tristan Bernard). Tristan Bernard's grandson Christian Bernard is the current Imperator of the Rosicrucian organization AMORC. One of his grand-nephews is Francis Veber, a screenwriter, director and playwright whose films have been frequently remade or adapted in Hollywood.

Works

Plays

- Les Pieds nickelés (1895)

- L'Anglais tel qu'on le parle (French Without a Master) (1899)

- Triplepatte (with André Godfernaux, 1905)

- The Brighton Twins (Les Jumeaux de Brighton) (1908)

- Le Danseur inconnu (1909)

- Le Costaud des épinettes (with Alfred Athis, 1910)

- The Little Cafe (Le petit café) (1911)

- Les Deux Canards (with Alfred Athis, 1913)

- Jeanne Doré (1913)

- Coeur de lilas (with Charles-Henry Hirsch, 1921)

- Le Cordon bleu (1923)

- Embrassez-moi (with Gustave Quinson and Yves Mirande, 1923)

Narrative works

- Vous m'en direz tant (1894) collaboration with Pierre Veber

- Contes de Pantruche et d'ailleurs (1897)

- Sous toutes réserves (1898)

- Mémoires d'un jeune homme rangé (1899)

- Un mari pacifique (1901)

- Amants et voleurs (1905)

- Mathilde et ses mitaines (1912)

- L'Affaire Larcier (1924)

- Le Voyage imprévu (1928)

- Aux abois (1933)

- Robin des bois (1935)

Filmography

- Jeanne Doré, directed by Louis Mercanton and René Hervil (1915, based on the play Jeanne Doré)

- The Love Cheat, directed by George Archainbaud (1919, based on the play Le Danseur inconnu)

- The Little Cafe, directed by Raymond Bernard (1919, based on the play The Little Cafe)

- Triplepatte, directed by Raymond Bernard (1922, based on the play Triplepatte)

- Le Costaud des épinettes, directed by Raymond Bernard (1923, based on the play Le Costaud des épinettes)

- Kiss Me, directed by Robert Péguy (1929, based on the play Embrassez-moi)

- The Unknown Dancer, directed by René Barberis (1929, based on the play Le Danseur inconnu)

- Playboy of Paris, directed by Ludwig Berger (1930, based on the play The Little Cafe)

- The Little Cafe, directed by Ludwig Berger (1931, based on the play The Little Cafe)

- Le Poignard malais, directed by Roger Goupillières (1931, based on a short story)

- L'Anglais tel qu'on le parle, directed by Robert Boudrioz (1931, based on the play L'Anglais tel qu'on le parle)

- The Champion Cook, directed by Karl Anton (1932, based on the play Le Cordon bleu)

- Coeur de lilas, directed by Anatole Litvak (1932, based on the play Coeur de lilas)

- Kiss Me, directed by Léon Mathot (1932, based on the play Embrassez-moi)

- Les Deux Canards, directed by Erich Schmidt (1934, based on the play Les Deux Canards)

- Le Voyage imprévu, directed by Jean de Limur (1935, based on the novel Le Voyage imprévu)

- Runaway Ladies, directed by Jean de Limur (1938, based on the novel Le Voyage imprévu)

- Amants et Voleurs, directed by Raymond Bernard (1935, based on the play Le Costaud des épinettes)

- The Brighton Twins, directed by Claude Heymann (1936, based on the play The Brighton Twins)

- Jeanne Doré, directed by Mario Bonnard (Italy, 1938, based on the play Jeanne Doré)

- The Last Metro, directed by Maurice de Canonge (1945, based on the novel Mathilde et ses mitaines)

- Aux abois, directed by Philippe Collin (2005, based on the novel Aux abois)

Screenwriter

- Le Ravin sans fond (dir. Jacques Feyder and Raymond Bernard, 1917)

- L'Homme inusable (dir. Raymond Bernard, 1923)

- Décadence et grandeur (dir. Raymond Bernard, 1923)

- The Fortune (dir. Jean Hémard, 1931)

- Eusèbe député (dir. André Berthomieu, 1938)

- Girls in Distress (dir. G. W. Pabst, 1939)

References

- Who Was Who in the Theatre:1912–1976, p.197 vol.1 A-C;compiled from editions published annually by John Parker – 1976 edition by Gale Research ISBN 0-8103-0406-6 (UK) ISBN 0-273-01313-0

- Cycling, A Hands, La Chaine Simpson

- Leeds.ac.uk – 73.200–213 The Contribution of the Fine Arts to the Olympic Games, De Coubertin on Fine Art in the Olympic Movement Archived 13 April 2001 at the Wayback Machine

External links

Media related to Tristan Bernard at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tristan Bernard at Wikimedia Commons French Wikisource has original text related to this article: Auteur:Tristan Bernard

French Wikisource has original text related to this article: Auteur:Tristan Bernard