True Cross

The True Cross is the name for physical remnants which, by the tradition of some Christian churches, are said to be from the cross upon which Jesus was crucified.[1]

According to post-Nicene historians such as Socrates of Constantinople, Empress Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, the first Christian emperor of Rome, travelled to the Holy Land in 326–328, finding churches and establishing relief agencies for the poor. Historians Gelasius of Caesarea (died 395) and Rufinus (344/45-411) claimed that she discovered the hiding place of three crosses that were believed to have been used at the crucifixion of Jesus and the two thieves, St. Dismas and Gestas, executed with him. To one cross was affixed the titulus bearing Jesus's name, but Helena was not sure until a miracle revealed that this was the True Cross.

Many churches possess fragmentary remains that are by tradition alleged to be those of the True Cross. While the bulk of Roman Catholic and Orthodox believers recognize them as genuine pieces of the cross of Christ, their authenticity is disputed by other Christians, mainly Protestants.[2] In 2016 a fragment held by Waterford cathedral was tested by Oxford University radiocarbon experts and found to date from the 11th century, a period during which forged relics were common.[3]

The acceptance and belief of the True Cross tradition of the early Christian Church is generally restricted to the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Church, and the Church of the East. The medieval legends that developed concerning the provenance of the True Cross differ between Catholic and Orthodox tradition.

Provenance

The Golden Legend

In the Latin-speaking traditions of Western Europe, the story of the pre-Christian origins of the True Cross was well established by the 13th century when, in 1260, it was recorded by Jacopo de Voragine, Bishop of Genoa, in the Golden Legend.[4]

The Golden Legend contains several versions of the origin of the True Cross. In The Life of Adam, Voragine writes that the True Cross came from three trees which grew from three seeds from the "Tree of Mercy" which Seth collected and planted in the mouth of Adam's corpse.[5]

In another account contained in Of the invention of the Holy Cross, and first of this word invention, Voragine writes that the True Cross came from a tree that grew from part of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, or "the tree that Adam ate of", that Seth planted on Adam's grave where it "endured there unto the time of Solomon".[6][7] Alternatively, it reached Solomon via Moses, whose rod it was, and David, who planted it at Jerusalem. It was felled by Solomon to be a beam in his Temple of Solomon, but not found suitable in the end.[8]

After many centuries, the tree was cut down and the wood used to build a bridge over which the Queen of Sheba passed, on her journey to meet King Solomon. So struck was she by the portent contained in the timber of the bridge that she fell on her knees and revered it. On her visit to Solomon, she told him that a piece of wood from the bridge would bring about the replacement of God's covenant with the Jewish people by a new order. Solomon, fearing the eventual destruction of his people, had the timber buried.[9][10]

After fourteen generations, the wood taken from the bridge was fashioned into the Cross used to crucify Jesus Christ.[9][11] Voragine then goes on to describe its finding by Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine.[9]

Acceptance of this tradition

In the late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance, there was a wide general acceptance of the origin of the True Cross and its history preceding the crucifixion of Jesus, as recorded by Voragine. This general acceptance is confirmed by the numerous artworks that depict this subject, culminating in one of the most famous fresco cycles of the Renaissance, the Legend of the True Cross by Piero della Francesca, painted on the walls of the chancel of the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo between 1452 and 1466, in which he reproduces faithfully the traditional episodes of the story as recorded in The Golden Legend.

Eastern Christianity

According to the sacred tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church the True Cross was made from three different types of wood: cedar, pine and cypress.[12] This is an allusion to Isaiah 60:13: "The glory of Lebanon shall come unto thee, the fir tree, the pine tree, and the box [cypress] together to beautify the place of my sanctuary, and I will make the place of my feet glorious." The link between this verse and the crucifixion lies in the words "the place of my feet", which is interpreted as referring to the suppedāneum (foot rest) on which Jesus' feet were nailed (see Orthodox cross). (Compare with the Jewish concept of the Ark of the Covenant, or indeed the Jerusalem Temple, as being the resting place for God's foot-stool,[13] and the prescribed Three Pilgrimage Festivals, in Hebrew aliya la-regel, lit. ascending to the foot).[14]

Tradition of Lot's triple tree

There is a tradition that the three trees (cedar, pine and cypress – see above) from which the True Cross was constructed grew together in one spot. A traditional Orthodox icon depicts Lot, the nephew of Abraham, watering the trees.[12] According to tradition, these trees were used to construct the Temple in Jerusalem ("to beautify the place of my sanctuary"). Later, during Herod's reconstruction of the Temple, the wood from these trees was removed from the Temple and discarded, eventually being used to construct the cross on which Jesus was crucified ("and I will make the place of my feet glorious").

Finding the True Cross

Eusebius: no mention of the True Cross

Eusebius of Caesarea (died 339) who, through his Life of Constantine, is the earliest and main historical source on the rediscovery of the Tomb of Jesus and the construction of the first church at the site, does not mention the finding of the True Cross.[15]

In his Life of Constantine, Eusebius describes how the site of the Holy Sepulchre, once a site of veneration for the early Christian Church in Jerusalem, had been covered over with earth and a temple of Venus had been built on top. Although Eusebius does not say as much, this would probably have been done as part of Hadrian's reconstruction of Jerusalem as a new pagan city, Aelia Capitolina, after 130, following the destruction of the formerly Jewish city at the end of the Jewish Revolt in the year 70, and in connection with Bar Kokhba's revolt of 132–135. Following his conversion to Christianity, Emperor Constantine ordered in about 325–326 that the site be uncovered and instructed Macarius, Bishop of Jerusalem, to build a church on the site. Eusebius' work contains details about the demolition of the pagan temple and the erection of the church, but doesn't mention anywhere the finding of the True Cross.[15]

According to Socrates Scholasticus

Socrates Scholasticus (born c. 380), in his Ecclesiastical History, gives a full description of the discovery[16] that was repeated later by Sozomen (c. 400 – c. 450 AD) and by Theodoret (c. 393 – c. 458/466). In it he describes how Helena Augusta, Constantine's aged mother, had the pagan temple destroyed and the Sepulchre uncovered, whereupon three crosses, the titulus, and the nails from Jesus's crucifixion were uncovered as well. In Socrates' version of the story, Macarius had the three crosses placed in turn on a deathly ill woman. This woman recovered at the touch of the third cross, which was taken as a sign that this was the cross of Christ, the new Christian symbol. Socrates also reports that, having also found the Holy Nails (the nails with which Christ had been fastened to the cross), Helena sent these to Constantinople, where they were incorporated into the emperor's helmet and the bridle of his horse.

According to Sozomen

Sozomen (died c. 450), in his Ecclesiastical History, gives essentially the same version as Socrates. He also adds that it was said (by whom he does not say) that the location of the Sepulchre was "disclosed by a Hebrew who dwelt in the East, and who derived his information from some documents which had come to him by paternal inheritance" (although Sozomen himself disputes this account) and that a dead person was also revived by the touch of the Cross. Later popular versions of this story state that the Jew who assisted Helena was named Jude or Judas, but later converted to Christianity and took the name Kyriakos.

According to Theodoret

Theodoret (died c. 457) in his Ecclesiastical History Chapter xvii gives what would become the standard version of the finding of the True Cross:

When the empress beheld the place where the Saviour suffered, she immediately ordered the idolatrous temple, which had been there erected, to be destroyed, and the very earth on which it stood to be removed. When the tomb, which had been so long concealed, was discovered, three crosses were seen buried near the Lord's sepulchre. All held it as certain that one of these crosses was that of our Lord Jesus Christ, and that the other two were those of the thieves who were crucified with Him. Yet they could not discern to which of the three the Body of the Lord had been brought nigh, and which had received the outpouring of His precious Blood. But the wise and holy Macarius, the president of the city, resolved this question in the following manner. He caused a lady of rank, who had been long suffering from disease, to be touched by each of the crosses, with earnest prayer, and thus discerned the virtue residing in that of the Saviour. For the instant this cross was brought near the lady, it expelled the sore disease, and made her whole.

With the Cross were also found the Holy Nails, which Helena took with her back to Constantinople. According to Theodoret, "She had part of the cross of our Saviour conveyed to the palace. The rest was enclosed in a covering of silver, and committed to the care of the bishop of the city, whom she exhorted to preserve it carefully, in order that it might be transmitted uninjured to posterity."

Syriac tradition

Another popular ancient version from the Syriac tradition replaced Helena with a fictitious first-century empress named Protonike, who is said to be the wife of emperor Claudius.[17] This story, which originated in Edessa in the 430s,[18] was transmitted in the so-called Doctrina Addai, which was believed to be written by Thaddeus of Edessa (Addai in Syriac texts), one of the seventy disciples.[19]

The narrative retrojected the Helena version to the first century. In the story, Protonike traveled to Jerusalem after she met Simon Peter in Rome.[17] She was shown around the city by James, the brother of Jesus, until she discovered the cross after it healed her daughter of some illness.[17] She then converted to Christianity and had a church built on Golgotha.[17]

Aside from the Syriac tradition, the Protonike version was also cited by Armenian sources.[20]

Religious commemoration within the Catholic Church

According to the 1955 Roman Catholic Marian Missal, Helena went to Jerusalem to search for the True Cross and found it September 14, 320. In the eighth century, the feast of the Finding was transferred to May 3, and September 14 became the celebration of the "Exaltation of the Cross", the commemoration of a victory over the Persians by Heraclius, as a result of which the relic was returned to Jerusalem.

The relics of the Cross in Jerusalem

After Empress Helena

The silver reliquary that was left at the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre in care of the bishop of Jerusalem was exhibited periodically to the faithful. In the 380s a nun named Egeria who was travelling on pilgrimage described the veneration of the True Cross at Jerusalem in a long letter, the Itinerarium Egeriae that she sent back to her community of women:

Then a chair is placed for the bishop in Golgotha behind the [liturgical] Cross, which is now standing; the bishop duly takes his seat in the chair, and a table covered with a linen cloth is placed before him; the deacons stand round the table, and a silver-gilt casket is brought in which is the holy wood of the Cross. The casket is opened and [the wood] is taken out, and both the wood of the Cross and the title are placed upon the table. Now, when it has been put upon the table, the bishop, as he sits, holds the extremities of the sacred wood firmly in his hands, while the deacons who stand around guard it. It is guarded thus because the custom is that the people, both faithful and catechumens, come one by one and, bowing down at the table, kiss the sacred wood and pass through. And because, I know not when, some one is said to have bitten off and stolen a portion of the sacred wood, it is thus guarded by the deacons who stand around, lest any one approaching should venture to do so again. And as all the people pass by one by one, all bowing themselves, they touch the Cross and the title, first with their foreheads and then with their eyes; then they kiss the Cross and pass through, but none lays his hand upon it to touch it. When they have kissed the Cross and have passed through, a deacon stands holding the ring of Solomon and the horn from which the kings were anointed; they kiss the horn also and gaze at the ring...[21]

Before long, but perhaps not until after the visit of Egeria, it was possible also to venerate the crown of thorns, the pillar at which Christ was scourged, and the lance that pierced his side.

During Persian–Byzantine war (614–30)

In 614 the Sassanid Emperor Khosrau II ("Chosroes") removed the part of the cross held in Jerusalem as a trophy, after he captured the city. Thirteen years later, in 628, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius defeated Khosrau and regained the relic from Shahrbaraz. He placed the cross in Constantinople at first, and took it back to Jerusalem on 21 March 630.[22] Some scholars disagree with this narrative, Professor Constantin Zuckerman going as far as to suggest that the True Cross was actually lost by the Persians, and that the wood contained in the allegedly still sealed reliquary brought to Jerusalem by Heraclius in 629 was a fake. In his analysis, the hoax was designed to serve the political purposes of both Heraclius and his former foe, recently turned ally and co-father-in-law, Persian general and soon-to-become king Shahrbaraz.[23]

Fatimids, Crusaders and loss of the Cross

Around 1009, the year in which Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Christians in Jerusalem hid part of the cross and it remained hidden until the city was taken by the European soldiers of the First Crusade. Arnulf Malecorne, the first Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, had the Greek Orthodox priests who were in possession of the Cross tortured in order to reveal its location.[24] The relic that Arnulf discovered was a small fragment of wood embedded in a golden cross, and it became the most sacred relic of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, with none of the controversy that had followed their discovery of the Holy Lance in Antioch. It was housed in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre under the protection of the Latin Patriarch, who marched with it ahead of the army before every battle.

After King Baldwin I of Jerusalem presented King Sigurd I of Norway with a splinter of the True Cross following the Norwegian Crusade in 1110, the Cross was captured by Saladin during the Battle of Hattin in 1187, and while some Christian rulers, like Richard the Lionheart,[25] Byzantine emperor Isaac II Angelos and Tamar, Queen of Georgia, sought to ransom it from Saladin,[26] the cross was not returned.

In 1219 the True Cross was offered to the Knights Templar by Al-Kamil in exchange for lifting the siege on Damietta. The cross was never delivered as Al-Kamil did not, in fact, have it. Subsequently the cross disappeared from historical records. The True Cross was last seen in the city of Damascus.[27]

Current relic

Currently the Greek Orthodox church presents a small True Cross relic shown in the Greek Treasury at the foot of Golgotha, within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[28] The Syriac Orthodox Church also has a small relic of the True Cross in St Mark Monastery, Jerusalem. The Armenian Apostolic Church also has a small shard from the True Cross.[29]

Dispersal of relics

An inscription of 359, found at Tixter, in the neighbourhood of Sétif in Mauretania (in today Algeria), was said to mention, in an enumeration of relics, a fragment of the True Cross, according to an entry in Roman Miscellanies, X, 441.

Fragments of the Cross were broken up, and the pieces were widely distributed; in 348, in one of his Catecheses, Cyril of Jerusalem remarked that the "whole earth is full of the relics of the Cross of Christ,"[30] and in another, "The holy wood of the Cross bears witness, seen among us to this day, and from this place now almost filling the whole world, by means of those who in faith take portions from it."[30] Egeria's account testifies to how highly these relics of the crucifixion were prized. Saint John Chrysostom relates that fragments of the True Cross were kept in golden reliquaries, "which men reverently wear upon their persons." Even two Latin inscriptions around 350 from today's Algeria testify to the keeping and admiration of small particles of the cross.[31] Around the year 455, Juvenal Patriarch of Jerusalem sent to Pope Leo I a fragment of the "precious wood", according to the Letters of Pope Leo. A portion of the cross was taken to Rome in the seventh century by Pope Sergius I, who was of Byzantine origin. "In the small part is power of the whole cross", says an inscription in the Felix Basilica of Nola, built by bishop Paulinus at the beginning of 5th century. The cross particle was inserted in the altar.[32]

The Old English poem Dream of the Rood mentions the finding of the cross and the beginning of the tradition of the veneration of its relics. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also talks of King Alfred receiving a fragment of the cross from Pope Marinus (see: Annal Alfred the Great, year 883).[33] Although it is possible, the poem need not be referring to this specific relic or have this incident as the reason for its composition. However, there is a later source that speaks of a bequest made to the 'Holy Cross' at Shaftesbury Abbey in Dorset; Shaftesbury abbey was founded by King Alfred, supported with a large portion of state funds and given to the charge of his own daughter when he was alive – it is conceivable that if Alfred really received this relic, that he may have given it to the care of the nuns at Shaftesbury. [34]

Most of the very small relics of the True Cross in Europe came from Constantinople. The city was captured and sacked by the Fourth Crusade in 1204: "After the conquest of the city Constantinople inestimable wealth was found: incomparably precious jewels and also a part of the cross of the Lord, which Helena transferred from Jerusalem and [which] was decorated with gold and precious jewels. There it attained [the] highest admiration. It was carved up by the present bishops and was divided with other very precious relics among the knights; later, after their return to the homeland, it was donated to churches and monasteries."[35][36][37] A knight Robert de Clari wrote: "Within this chapel were found many precious relics; for therein were found two pieces of the True Cross, as thick as a man's leg and a fathom in length."[38]

By the end of the Middle Ages so many churches claimed to possess a piece of the True Cross, that John Calvin is famously said to have remarked that there was enough wood in them to fill a ship:

There is no abbey so poor as not to have a specimen. In some places there are large fragments, as at the Holy Chapel in Paris, at Poitiers, and at Rome, where a good-sized crucifix is said to have been made of it. In brief, if all the pieces that could be found were collected together, they would make a big ship-load. Yet the Gospel testifies that a single man was able to carry it.

— Calvin, Traité Des Reliques

Conflicting with this is the finding of Charles Rohault de Fleury, who, in his Mémoire sur les instruments de la Passion of 1870 made a study of the relics in reference to the criticisms of Calvin and Erasmus. He drew up a catalogue of all known relics of the True Cross showing that, in spite of what various authors have claimed, the fragments of the Cross brought together again would not reach one-third that of a cross which has been supposed to have been three or four metres (9.8 or 13.1 feet) in height, with transverse branch of two metres (6.6 feet) wide, proportions not at all abnormal. He calculated: supposing the Cross to have been of pine-wood (based on his microscopic analysis of the fragments) and giving it a weight of about seventy-five kilogrammes, we find the original volume of the cross to be 0.178 cubic metres (6.286 cubic feet). The total known volume of known relics of the True Cross, according to his catalogue, amounts to approximately 0.004 cubic metres (0.141 cubic feet) (more specifically 3,942,000 cubic millimetres), leaving a volume of 0.174 m3 (6.145 cu ft), almost 98%, lost, destroyed, or from which is otherwise unaccounted.[39]

Four cross particles – of ten particles with surviving documentary provenances by Byzantine emperors – from European churches, i.e. Santa Croce in Rome, Caravaca de la Cruz, Notre Dame, Paris, Pisa Cathedral and Florence Cathedral, were microscopically examined. "The pieces came all together from olive."[40] It is possible that many alleged pieces of the True Cross are forgeries, created by travelling merchants in the Middle Ages, during which period a thriving trade in manufactured relics existed.

Gerasimos Smyrnakis[41] notes that the largest surviving portion, of 870,760 cubic millimetres, is preserved in the Monastery of Koutloumousiou on Mount Athos, and also mentions the preserved relics in Rome (consisting of 537,587 cubic millimetres), in Brussels (516,090 cubic millimetres), in Venice (445,582 cubic millimetres), in Ghent (436,450 cubic millimetres) and in Paris (237,731 cubic millimetres). (For comparison, the collective volume of the largest of these sets of fragments would be equivalent to a cube of a little less than 4 inches (10 cm) per side, while the smallest of these would have an equivalent cubic dimension of about 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) per side. The volume figures given by Smyrnakis for these objects—six significant figures and to the cubic millimeter—are undoubtedly the result of multiplying slightly approximate numbers and should not be seen as implying scientific accuracy of the highest order in a book written over a century ago.)

Santo Toribio de Liébana in Spain is also said to hold the largest of these pieces and is one of the most visited Roman Catholic pilgrimage sites. In Asia, the only place where the other part of the True Cross is located is in the Monasterio de Tarlac at San Jose, Tarlac, Philippines.[42]

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church also claims to have the right wing of the true cross buried in the monastery of Gishen Mariam. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has an annual religious holiday, called Meskel or Demera, commemorating the discovery of the True Cross by Queen Helena. Meskel occurs on 17 Meskerem in the Ethiopian calendar (September 27, Gregorian calendar, or September 28 in leap years). "Meskel" (or "Meskal" or "Mesqel"; there are various ways to transliterate from Ge'ez to Latin script) is Ge'ez for "cross".[43]

The festival is known as Feast of the exaltation of the holy cross in other Orthodox, Catholic or Protestant churches. The churches that follow the Gregorian calendar celebrate the feast on September 14.

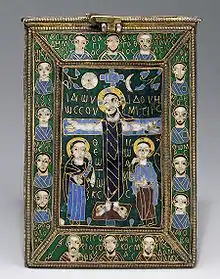

An enamelled silver reliquary of the True Cross from Constantinople, c. 800

An enamelled silver reliquary of the True Cross from Constantinople, c. 800 One of the largest purported fragments of the True Cross is at Santo Toribio de Liébana in Spain (photo by F. J. Díez Martín)

One of the largest purported fragments of the True Cross is at Santo Toribio de Liébana in Spain (photo by F. J. Díez Martín).JPG.webp) A "Kreuzpartikel" or fragment of True Cross in the Schatzkammer (Vienna)

A "Kreuzpartikel" or fragment of True Cross in the Schatzkammer (Vienna) Fragments of True Cross in the Serbian Orthodox Monastery of Visoki Dečani in Kosovo

Fragments of True Cross in the Serbian Orthodox Monastery of Visoki Dečani in Kosovo

Veneration

Saint John Chrysostom wrote homilies on the three crosses:

Kings removing their diadems take up the cross, the symbol of their Saviour's death; on the purple, the cross; in their prayers, the cross; on their armour, the cross; on the holy table, the cross; throughout the universe, the cross. The cross shines brighter than the sun.

The Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Church, the Anglican Communion, and a number of Protestant denominations, celebrate the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross on September 14, the anniversary of the dedication of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In later centuries, these celebrations also included commemoration of the rescue of the True Cross from the Persians in 628. In the Galician usage, beginning about the seventh century, the Feast of the Cross was celebrated on May 3. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, when the Galician and Roman practices were combined, the September date, for which the Vatican adopted the official name "Triumph of the Cross" in 1963, was used to commemorate the rescue from the Persians and the May date was kept as the "Invention of the True Cross" to commemorate the finding.[44] The September date is often referred to in the West as Holy Cross Day; the May date (See also Roodmas.) was dropped from the liturgical calendar of the Roman Catholic Church in 1970 as part of the liturgical reforms mandated by the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). The Orthodox still commemorate both events on September 14, one of the Twelve Great Feasts of the liturgical year, and the Procession of the Venerable Wood of the Cross on 1 August, the day on which the relics of the True Cross would be carried through the streets of Constantinople to bless the city.[45]

In addition to celebrations on fixed days, there are certain days of the variable cycle when the Cross is celebrated. The Roman Catholic Church has a formal Adoration of the Cross (the term is inaccurate, but sanctioned by long use) during the services for Good Friday. In Eastern Orthodox churches everywhere, a replica of the cross is brought out in procession during Matins of Great and Holy Friday for the people to venerate. The Orthodox also celebrate an additional Veneration of the Cross on the third Sunday of Great Lent.

Image gallery

Reliquary of the True Cross at Notre Dame de Paris

Reliquary of the True Cross at Notre Dame de Paris Base of reliquary of the True Cross and nail of the crucifixion. Notre Dame de Paris.

Base of reliquary of the True Cross and nail of the crucifixion. Notre Dame de Paris. Reliquary of the True Cross and a nail of the crucifixion. Notre Dame de Paris.

Reliquary of the True Cross and a nail of the crucifixion. Notre Dame de Paris. Fragment, treasury of the former Premonstratensian Abbey in Rüti in Switzerland

Fragment, treasury of the former Premonstratensian Abbey in Rüti in Switzerland True Cross at Visoki Dečani, Kosovo

True Cross at Visoki Dečani, Kosovo The three crosses are discovered. An injured young man is healed by the True Cross. Fifteenth-century frescoes at the Church of San Francesco, Arezzo by Piero della Francesca.

The three crosses are discovered. An injured young man is healed by the True Cross. Fifteenth-century frescoes at the Church of San Francesco, Arezzo by Piero della Francesca.

See also

- Holy Grail, motif from the Arthurian literature

- Holyrood (cross)

- Île de la Cité

- Relics associated with Jesus

- Arma Christi

- Holy Chalice, chalice used at the Last Supper

- Holy Sponge

- Lance of Longinus

- Shroud of Turin

- Titulus Crucis

- Santa Croce in Gerusalemme

- Stavelot Triptych

- Tree of Jesse

References

Citations

- Sources for the legend of Helena and the invention of the True Cross are explored in detail in J. W. Drijvers, Helena Augusta, the Mother of Constantine the Great and the Legend of her Finding of the True Cross (Leiden, 1992).

See also: The Elene of Cynewulf. Yale Studies in English. Volume XXI (1904). Translated into English prose by Lucius Hudson Holt.CS1 maint: others (link) In Project Gutenberg. Archived 2009-09-24 at the Wayback Machine - Drijvers 1992.

- O'Shea, James (2016-07-25). "Truth revealed about Irish relic of cross on which Jesus was crucified (VIDEO)". Irish Central. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- The word "legend" did not imply "myth". The word, from the Latin, meant "script that is to be read". Thus the indisputably historic lives of early leaders of the Church, such as Gregory, Jerome and Augustine of Hippo were referred to as their "legends".

- "Voragine, The Golden Legend: The Life of Adam". Archived from the original on 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- "Voragine, The Golden Legend: Invention of the True Cross". Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- Herzog, 68

- Herzog, 68

- Jacopo de Voragine, The Golden Legend, late 13th century. Archived 2012-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Herzog, 68

- Herzog, 68

- Dr. Alexander Roman, "Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine", Ukrainian Orthodoxy Accessed on 2012-10-27

- Kittel, Gerhard; Friedrich, Gerhard, eds. (1969). Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Volume VI. Translated by Bromiley, Geoffrey W. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 627. ISBN 9780802822482.

- "Enormous 'foot-shaped' enclosure discovered in Jordan Valley". Science 2.0. 6 April 2009. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine". Archived from the original on 2004-09-07. Retrieved 2004-09-23.

- Socrates and Sozomenus; Philip Schaff, D.D., LL.D. and Henry Wace, D.D., ed. (1984). Chapter XVII—The Emperor's Mother Helena having come to Jerusalem, searches for and finds the Cross of Christ, and builds a Church. Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-8116-5. Archived from the original on 2011-11-09. Retrieved 2012-03-21.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Saint-Laurent, Jeanne-Nicole Mellon (2015). Missionary Stories and the Formation of the Syriac Churches. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-28496-8.

- Wiles, Maurice F.; Yarnold, Edward; Parvis, Paul M. (2001). Studia Patristica: Papers Presented at the Thirteenth International Conference on Patristic Studies Held in Oxford, 1999: Historica, Biblica Theologica et Philosophica. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-90-429-0881-9.

- Meerson, Michael; Schäfer, Peter (2014). Toledot Yeshu: The Life Story of Jesus: Two Volumes and Database. Vol. I: Introduction and Translation. Vol. II: Critical Edition. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck. p. 121. ISBN 9783161534812.

- The Church of the Holy Cross of Ałt‘amar: Politics, Art, Spirituality in the Kingdom of Vaspurakan. Leiden: BRILL. 2019-08-05. p. 167. ISBN 978-90-04-40038-2.

- M.L. McClure and C. L. Feltoe, ed. and trans.The Pilgrimage of Etheria, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London,(1919)

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 299. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Constantin Zuckerman (2013). Heraclius and the return of the Holy Cross. Constructing the Seventh Century. Travaux et mémoires (17). Paris: Association des amis du Centre d'histoire et civilisation de Byzance. pp. 197–218. ISBN 978-2-916716-45-9. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Runciman, Steven (1951). A History of the Crusades: Volume 1, The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 294. ISBN 0-521-34770-X.

- Malouf, Amin (1983). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes.

- Ciggaar, Krijnie & Teule, Herman (2003). East and West in the Crusader States (1996 first ed.). 38: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 90-429-1287-1.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Madden, Thomas F. (2005). The New Concise History of the Crusades. p. 76. ISBN 0-7425-3822-2.

- "Church of the Holy Sepulchre chapels". See The Holy Land. 2010-03-15. Archived from the original on 2016-01-10. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- "Relic of the True Cross to be on View at St. Vartan Cathedral". The Armenian Church: Eastern Diocese of America. 6 September 2018.

- "NPNF2-07. Cyril of Jerusalem, Gregory Nazianzen". Archived from the original on 2004-09-12. Retrieved 2004-09-23.

- Duval, Yvette, Loca sanctorum Africae, Rome 1982, p.331-337 and 351–353

- Ziehr, Wilhelm, Das Kreuz, Stuttgart 1997, page 62

- "Medieval Sourcebook: The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on Alfred the Great". Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- Studies in the Early History of Shaftesbury Abbey. Dorset County Council, 1999

- Original: Capta igitur urbe, divitiae repperiuntur inestimabiles, lapides preciosissime et incomparabiles, pars etiam ligni dominici, quod per Helenam de Iherosolimis translatum, auro et gemmis precioses insignitum in maxima illic veneratione habebatur, ab episcopis qui presentes aderant incisum, ab aliis preciosissimis reliquis per nobilis quosque partitur, et postea eis revertentibus ad natale solum, per ecclesias et cenobia distrbuitur. – German: Nach der Eroberung der Stadt wurden unschätzbare Reichtümer gefunden, unvergleichlich kostbare Edelsteine und auch ein Teil des Kreuzes des Herrn, das, von Helena aus Jerusalem überführt und mit Gold und kostbaren Edelsteinen geschmückt, dort höchste Verehrung erfuhr. Es wurde von den anwesenden Bischöfen zerstückelt und mit anderen sehr kostbaren Reliquien unter die Ritter aufgeteilt; später, nach deren Rückkehr in die Heimat, wurde es Kirchen und Klöstern gestiftet.

- Chronica regia Coloniensis (sub annorum 1238–1240), page 203. Original book in Brüssel, three writers, two painters, last writing: year 1238, in: Mittelalterliche Farbfassung als Interpretation der Architektur?; Waitz, Georg [Hrsg.], Monumenta Germaniae historica : [Scriptores] : Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum, 18, Hannover 1880, page 203 Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine (Pars Sexte, continuatio tertia monachi S. Pantaleon)

- See also: ten sections of relics of the True Cross with documentary proofs, in: de:Diskussion:Kreuzerhöhung

- Robert of Clari's account of the Fourth Crusade, chapter 82: "Of the Marvels of Constantinople" Archived 2006-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: The True Cross". Archived from the original on 2004-06-03. Retrieved 2004-06-29.

- (William Ziehr, Das Kreuz, Stuttgart 1997, p. 63) de:Diskussion:Kreuzerhöhung, in German.

- Gerasimos Smyrnakis, Το Αγιον Ορος (The Holy Mountain), Athens, 1903 (reprinted 1998), p. 378-379

- "Monasterio de Tarlac". Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- Meskel

- The term "Invention" is from the Latin invenire, "to find" (lit. "to come across"), and should not be understood in the modern sense of creating something new.

- "Procession of the Honorable Wood of the Life-Giving Cross of the Lord". Orthodox Church in America. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

Bibliography

- Herzog, Sadja. “Gossart, Italy, and the National Gallery's Saint Jerome Penitent.” Report and Studies in the History of Art, vol. 3, 1969, pp. 67-70, JSTOR, Accessed 29 Dec. 2020.

Further reading

- Alan V. Murray, "Mighty against the enemies of Christ: the relic of the True Cross in the armies of the Kingdom of Jerusalem" in The Crusades and their sources: essays presented to B. Hamilton ed. J. France, W. G. Zajac (Aldershot, 1998) pp. 217–238.

- A. Frolow, La relique de la Vraie Croix: recherches sur le développement d'un culte. Paris, 1961.

- Jean-Luc Deuffic (ed.), Reliques et sainteté dans l'espace médiéval, Pecia 8/11, 2005

- Massimo Olmi, Indagine sulla croce di Cristo, Torino 2015.

- Massimo Olmi, I segreti delle reliquie bibliche. Dall'Arca dell'Alleanza al calice dell'Ultima Cena, Xpublishing, Roma 2018.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: True Cross |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to True Cross. |

- Jan Willem Drijvers, "Helena Augusta": the three legends that circulated about the finding of the Cross, the Helena legend, the Protonike legend and the Judas Kyriakos legend, with references to the contemporary sources

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "True Cross," a Catholic view

- OCA Synaxarion: Exaltation of the Cross, traditional Orthodox view

- Fernand Cabrol, "The true Cross": a Catholic view

- The Holy Cross in Jerusalem

- Relic of the True Cross in Wrocław, Poland