University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge (legally, The Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars of the University of Cambridge) is a collegiate research university in Cambridge, United Kingdom. Founded in 1209[9] and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the second-oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's fourth-oldest surviving university.[10] The university grew out of an association of scholars who left the University of Oxford after a dispute with the townspeople.[11] The two English ancient universities share many common features and are jointly referred to as Oxbridge.

| |

| Latin: Universitas Cantabrigiens | |

| Motto | Latin: Hinc lucem et pocula sacra |

|---|---|

Motto in English | From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge |

| Type | Public research university |

| Established | c. 1209 |

| Endowment | £7.121 billion (including colleges) [3] |

| Budget | £2.192 billion (excluding colleges)[4] |

| Chancellor | The Lord Sainsbury of Turville |

| Vice-Chancellor | Professor Stephen J. Toope |

Academic staff | 7,913[5] |

Administrative staff | 3,615 (excluding colleges)[5] |

| Students | 23,247 (2019)[6] |

| Undergraduates | 12,354 (2019) |

| Postgraduates | 10,893 (2019) |

| Location | , |

| Campus | University town 288 hectares (710 acres)[7] |

| Colours | Cambridge Blue[8] |

| Athletics | The Sporting Blue |

| Affiliations | |

| Website | cam |

| |

Cambridge is formed from a variety of institutions which include 31 semi-autonomous constituent colleges and over 150 academic departments, faculties and other institutions organised into six schools. All the colleges are self-governing institutions within the university, each controlling its own membership and with its own internal structure and activities. All students are members of a college. Cambridge does not have a main campus, and its colleges and central facilities are scattered throughout the city. Undergraduate teaching at Cambridge is organised around weekly small-group supervisions in the colleges – a feature unique to the Oxbridge system. These are complemented by classes, lectures, seminars, laboratory work and occasionally further supervisions provided by the central university faculties and departments. Postgraduate teaching is provided predominantly centrally.

Cambridge University Press, a department of the university, is the oldest university press in the world and currently the second largest university press in the world. Cambridge Assessment, also a department of the university, is one of the world's leading examining bodies and provides assessment to over eight million learners globally every year. The university also operates eight cultural and scientific museums, including the Fitzwilliam Museum, as well as a botanic garden. Cambridge's libraries, of which there are 116, hold a total of around 16 million books, around nine million of which are in Cambridge University Library, a legal deposit library. The university is home to, but independent of, the Cambridge Union – the world's oldest debating society. The university is closely linked to the development of the high-tech business cluster known as 'Silicon Fen'. It is the central member of Cambridge University Health Partners, an academic health science centre based around the Cambridge Biomedical Campus.

By both endowment size and consolidated assets, Cambridge is the wealthiest university in the United Kingdom.[12] In the fiscal year ending 31 July 2019, the central university, excluding colleges, had a total income of £2.192 billion, of which £592.4 million was from research grants and contracts.[13] At the end of the same financial year, the central university and colleges together possessed a combined endowment of over £7.1 billion and overall consolidated net assets (excluding 'immaterial' historical assets) of over £12.5 billion.[16] It is a member of numerous associations and forms part of the 'golden triangle' of English universities.

Cambridge has educated many notable alumni, including eminent mathematicians, scientists, politicians, lawyers, philosophers, writers, actors, monarchs and other heads of state. As of October 2020, 121 Nobel laureates, 11 Fields Medalists, 7 Turing Award winners and 14 British prime ministers have been affiliated with Cambridge as students, alumni, faculty or research staff.[17] University alumni have won 194 Olympic medals.[18]

History

By the late 12th century, the Cambridge area already had a scholarly and ecclesiastical reputation, due to monks from the nearby bishopric church of Ely. However, it was an incident at Oxford which is most likely to have led to the establishment of the university: three Oxford scholars were hanged by the town authorities for the death of a woman, without consulting the ecclesiastical authorities, who would normally take precedence (and pardon the scholars) in such a case, but were at that time in conflict with King John. Fearing more violence from the townsfolk, scholars from the University of Oxford started to move away to cities such as Paris, Reading, and Cambridge. Subsequently, enough scholars remained in Cambridge to form the nucleus of a new university when it had become safe enough for academia to resume at Oxford.[9][19][20] In order to claim precedence, it is common for Cambridge to trace its founding to the 1231 charter from Henry III granting it the right to discipline its own members (ius non-trahi extra) and an exemption from some taxes; Oxford was not granted similar rights until 1248.[21]

A bull in 1233 from Pope Gregory IX gave graduates from Cambridge the right to teach "everywhere in Christendom".[22] After Cambridge was described as a studium generale in a letter from Pope Nicholas IV in 1290,[23] and confirmed as such in a bull by Pope John XXII in 1318,[24] it became common for researchers from other European medieval universities to visit Cambridge to study or to give lecture courses.[23]

Foundation of the colleges

The colleges at the University of Cambridge were originally an incidental feature of the system. No college is as old as the university itself. The colleges were endowed fellowships of scholars. There were also institutions without endowments, called hostels. The hostels were gradually absorbed by the colleges over the centuries, but they have left some traces, such as the name of Garret Hostel Lane.[25]

Hugh Balsham, Bishop of Ely, founded Peterhouse, Cambridge's first college, in 1284. Many colleges were founded during the 14th and 15th centuries, but colleges continued to be established until modern times, although there was a gap of 204 years between the founding of Sidney Sussex in 1596 and that of Downing in 1800. The most recently established college is Robinson, built in the late 1970s. However, Homerton College only achieved full university college status in March 2010, making it the newest full college (it was previously an "Approved Society" affiliated with the university).

In medieval times, many colleges were founded so that their members would pray for the souls of the founders, and were often associated with chapels or abbeys. The colleges' focus changed in 1536 with the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Henry VIII ordered the university to disband its Faculty of Canon Law[26] and to stop teaching "scholastic philosophy". In response, colleges changed their curricula away from canon law, and towards the classics, the Bible, and mathematics.

Nearly a century later, the university was at the centre of a Protestant schism. Many nobles, intellectuals and even commoners saw the ways of the Church of England as too similar to the Catholic Church, and felt that it was used by the Crown to usurp the rightful powers of the counties. East Anglia was the centre of what became the Puritan movement. In Cambridge, the movement was particularly strong at Emmanuel, St Catharine's Hall, Sidney Sussex and Christ's College.[27] They produced many "non-conformist" graduates who greatly influenced, by social position or preaching, some 20,000 Puritans who left for New England and especially the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Great Migration decade of the 1630s. Oliver Cromwell, Parliamentary commander during the English Civil War and head of the English Commonwealth (1649–1660), attended Sidney Sussex.

Mathematics and mathematical physics

Examination in mathematics was once compulsory for all undergraduates studying for the Bachelor of Arts degree, the main first degree at Cambridge in both arts and sciences. From the time of Isaac Newton in the later 17th century until the mid-19th century, the university maintained an especially strong emphasis on applied mathematics, particularly mathematical physics. The exam is known as a Tripos.[28] Students awarded first-class honours after completing the mathematics Tripos are termed wranglers, and the top student among them is the Senior Wrangler. The Cambridge Mathematical Tripos is competitive and has helped produce some of the most famous names in British science, including James Clerk Maxwell, Lord Kelvin and Lord Rayleigh.[29] However, some famous students, such as G. H. Hardy, disliked the system, feeling that people were too interested in accumulating marks in exams and not interested in the subject itself.

Pure mathematics at Cambridge in the 19th century achieved great things, but also missed out on substantial developments in French and German mathematics. Pure mathematical research at Cambridge finally reached the highest international standard in the early 20th century, thanks above all to G. H. Hardy, his collaborator J. E. Littlewood and Srinivasa Ramanujan. In geometry, W. V. D. Hodge brought Cambridge onto the international mainstream in the 1930s.

Although diversified in its research and teaching interests, Cambridge today maintains its strength in mathematics. Cambridge alumni have won six Fields Medals and one Abel Prize for mathematics, while individuals representing Cambridge have won four Fields Medals.[30]

Modern period

After the Cambridge University Act formalised the organisational structure of the university, the study of many new subjects was introduced, such as theology, history and modern languages.[31] Resources necessary for new courses in the arts, architecture and archaeology were donated by Viscount Fitzwilliam, of Trinity College, who also founded the Fitzwilliam Museum.[32] In 1847, Prince Albert was elected Chancellor of the University of Cambridge after a close contest with the Earl of Powis.[59] Albert used his position as Chancellor to campaign successfully for reformed and more modern university curricula, expanding the subjects taught beyond the traditional mathematics and classics to include modern history and the natural sciences.[60]Between 1896 and 1902, Downing College sold part of its land to build the Downing Site, with new scientific laboratories for anatomy, genetics and Earth sciences.[33] During the same period, the New Museums Site was erected, including the Cavendish Laboratory, which has since moved to the West Cambridge Site, and other departments for chemistry and medicine.[34]

The University of Cambridge began to award PhD degrees in the first third of the 20th century. The first Cambridge PhD in mathematics was awarded in 1924.[35]

In the First World War, 13,878 members of the university served and 2,470 were killed. Teaching, and the fees it earned, came almost to a stop and severe financial difficulties followed. As a consequence the university first received systematic state support in 1919, and a Royal Commission appointed in 1920 recommended that the university (but not the colleges) should receive an annual grant.[36] Following the Second World War, the university saw a rapid expansion of student numbers and available places; this was partly due to the success and popularity gained by many Cambridge scientists.[37]

Parliamentary representation

The university was one of only two universities to hold parliamentary seats in the Parliament of England and was later one of eight represented in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The constituency was created by a Royal Charter of 1603 and returned two members of parliament until 1950, when it was abolished by the Representation of the People Act 1948.

The constituency was not a geographical area. Its electorate consisted of the graduates of the university. Before 1918 the franchise was restricted to male graduates with a doctorate or MA degree.

Women's education

For many years only male students were enrolled into the university. The first colleges for women were Girton College (founded by Emily Davies) in 1869 and Newnham College in 1872 (founded by Anne Clough and Henry Sidgwick), followed by Hughes Hall in 1885 (founded by Elizabeth Phillips Hughes as the Cambridge Teaching College for Women), Murray Edwards College (founded by Rosemary Murray as New Hall) in 1954, and Lucy Cavendish College in 1965. The first women students were examined in 1882 but attempts to make women full members of the university did not succeed until 1948.[38] Women were allowed to study courses, sit examinations, and have their results recorded from 1881; for a brief period after the turn of the twentieth century, this allowed the "steamboat ladies" to receive ad eundem degrees from the University of Dublin.[39]

From 1921 women were awarded diplomas which "conferred the Title of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts". As they were not "admitted to the Degree of Bachelor of Arts" they were excluded from the governing of the university. Since students must belong to a college, and since established colleges remained closed to women, women found admissions restricted to colleges established only for women. Darwin College, the first wholly graduate college of the university, matriculated both men and women students from its inception in 1964 – and elected a mixed fellowship. Of the undergraduate colleges, starting with Churchill, Clare and King's Colleges, the former men's colleges began to admit women between 1972 and 1988. One of the female-only colleges, Girton, also began to admit male students from 1979, but the other female-only colleges did not do likewise. As a result of St Hilda's College, Oxford, ending its ban on male students in 2008, Cambridge is now the only remaining United Kingdom university with female-only colleges (Newnham, Murray Edwards and Lucy Cavendish).[40][41] In the academic year 2004–5, the university's student sex ratio, including post-graduates, was male 52%: female 48%.[42]

Myths, legends and traditions

As an institution with such a long history, the university has developed a large number of myths and legends. The vast majority of these are untrue, but have been propagated nonetheless by generations of students and tour guides.

A discontinued tradition is that of the wooden spoon, the 'prize' awarded to the student with the lowest passing honours grade in the final examinations of the Mathematical Tripos. The last of these spoons was awarded in 1909 to Cuthbert Lempriere Holthouse, an oarsman of the Lady Margaret Boat Club of St John's College. It was over one metre in length and had an oar blade for a handle. It can now be seen outside the Senior Combination Room of St John's. Since 1908, examination results have been published alphabetically within class rather than in strict order of merit. This made it harder to ascertain who was "entitled" to the spoon (unless there was only one person in the third class), and so the practice was abandoned.

Each Christmas Eve, BBC radio and television broadcasts The Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols sung by the Choir of King's College, Cambridge. The radio broadcast has been a national Christmas tradition since it was first transmitted in 1928 (though the festival has existed since 1918). The radio broadcast is carried worldwide by the BBC World Service and is also syndicated to hundreds of radio stations in the US. The first television broadcast of the festival was in 1954.[43][44]

Locations and buildings

Buildings

The university occupies a central location within the city of Cambridge, with the students taking up a significant proportion (nearly 20%) of the town's population and heavily affecting the age structure.[45] Most of the older colleges are situated nearby the city centre and river Cam, along which it is traditional to punt to appreciate the buildings and surroundings.[46]

Examples of notable buildings include King's College Chapel,[47] the history faculty building[48] designed by James Stirling; and the Cripps Building at St John's College.[49] The brickwork of several of the colleges is also notable: Queens' College contains "some of the earliest patterned brickwork in the country"[50] and the brick walls of St John's College provide examples of English bond, Flemish bond and Running bond.[51]

Sites

The university is divided into several sites where the different departments are placed. The main ones are:[52]

- Addenbrooke's

- Downing Site

- Madingley/Girton

- New Museums Site

- Old Addenbroke's

- Old Schools

- Silver Street/Mill Lane

- Sidgwick Site

- West Cambridge

- North West Cambridge Development

The university's School of Clinical Medicine is based in Addenbrooke's Hospital where students in medicine undergo their three-year clinical placement period after obtaining their BA degree,[53] while the West Cambridge site is undergoing a major expansion and will host a new sports development.[54] In addition, the Judge Business School, situated on Trumpington Street, provides management education courses since 1990 and is consistently ranked within the top 20 business schools globally by the Financial Times.[55]

Given that the sites are in relative close proximity to each other and the area around Cambridge is reasonably flat, one of the favourite modes of transport for students is the bicycle: a fifth of the journeys in the city are made by bike, a figure enhanced by the fact that students are not permitted to hold car park permits, except under special circumstances.[56]

'Town and gown'

The relationship between the university and the city has not always been positive. The phrase town and gown is employed to differentiate inhabitants of Cambridge from students at the university, who historically wore academical dress. There are many stories of ferocious rivalry between the two categories. During the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, strong clashes brought about attacks and looting of university properties while locals contested the privileges granted by the government to the academic staff, the university's ledgers being burned in Market Square to the rallying cry "Away with the learning of clerks, away with it!".[57] Following these events, the Chancellor was given special powers allowing him to prosecute the criminals and re-establish order in the city. Attempts to reconcile the two groups followed over time, and in the 16th century agreements were signed to improve the quality of streets and student accommodation around the city. However, this was followed by new confrontations when the plague hit Cambridge in 1630 and colleges refused to help those affected by the disease by locking their sites.[58]

Nowadays, these conflicts have somewhat subsided and the university has become an opportunity for employment among the population, providing an increased level of wealth in the area.[59] The enormous growth in the number of high-tech, biotech, providers of services and related firms situated near Cambridge has been termed the Cambridge Phenomenon: the addition of 1,500 new, registered companies and as many as 40,000 jobs between 1960 and 2010 has been directly related to the presence and importance of the university.[60]

Organisation and administration

Cambridge is a collegiate university, meaning that it is made up of self-governing and independent colleges, each with its own property and income. Most colleges bring together academics and students from a broad range of disciplines, and within each faculty, school or department within the university, academics from many different colleges will be found.

The faculties are responsible for ensuring that lectures are given, arranging seminars, performing research and determining the syllabi for teaching, overseen by the General Board. Together with the central administration headed by the Vice-Chancellor, they make up the entire Cambridge University. Facilities such as libraries are provided on all these levels: by the university (the Cambridge University Library), by the Faculties (Faculty libraries such as the Squire Law Library), and by the individual colleges (all of which maintain a multi-discipline library, generally aimed mainly at their undergraduates).

Colleges

The colleges are self-governing institutions with their own endowments and property, founded as integral parts of the university. All students and most academics are attached to a college. Their importance lies in the housing, welfare, social functions, and undergraduate teaching they provide. All faculties, departments, research centres, and laboratories belong to the university, which arranges lectures and awards degrees, but undergraduates receive their supervisions—small-group teaching sessions, often with just one student—within the colleges (though in many cases students go to other colleges for supervision if the teaching fellows at their college do not specialise in the areas concerned). Each college appoints its own teaching staff and fellows, who are also members of a university department. The colleges also decide which undergraduates to admit to the university, in accordance with university regulations.

Cambridge has 31 colleges, of which two, Murray Edwards and Newnham, admit women only. The other colleges are mixed, though most were originally all-male. Darwin was the first college to admit both men and women, while Churchill, Clare, and King's were the first previously all-male colleges to admit female undergraduates, in 1972. Magdalene became the last all-male college to accept women, in 1988.[61] Clare Hall and Darwin admit only postgraduates, and Hughes Hall, St Edmund's and Wolfson admit only mature (i.e. 21 years or older on date of matriculation) students, encompassing both undergraduate and graduate students. Lucy Cavendish, which was previously a women-only mature college, announced that they would admit men and women from the age of 18 from 2021 onwards.[62] All other colleges admit both undergraduate and postgraduate students with no age restrictions.

Colleges are not required to admit students in all subjects, with some colleges choosing not to offer subjects such as architecture, history of art or theology, but most offer close to the complete range. Some colleges maintain a bias towards certain subjects, for example with Churchill leaning towards the sciences and engineering,[63] while others such as St Catharine's aim for a balanced intake.[64] Others maintain much more informal reputations, such as for the students of King's to hold left-wing political views,[65] or Robinson's and Churchill's attempts to minimise their environmental impact.[66]

Costs to students (accommodation and food prices) vary considerably from college to college.[67][68] Similarly, college expenditure on student education also varies widely between individual colleges.[69]

There are also several theological colleges in Cambridge, separate from Cambridge University, including Westcott House, Westminster College and Ridley Hall Theological College, that are, to a lesser degree, affiliated to the university and are members of the Cambridge Theological Federation.[70]

The 31 colleges are:[71]

Christ's

Christ's Churchill

Churchill Clare

Clare Clare Hall

Clare Hall Corpus Christi

Corpus Christi Darwin

Darwin Downing

Downing Emmanuel

Emmanuel Fitzwilliam

Fitzwilliam Girton

Girton Gonville & Caius

Gonville & Caius Homerton

Homerton Hughes Hall

Hughes Hall_shield.svg.png.webp) Jesus

Jesus King's

King's Lucy Cavendish

Lucy Cavendish Magdalene

Magdalene Murray Edwards

Murray Edwards Newnham

Newnham_shield.svg.png.webp) Pembroke

Pembroke Peterhouse

Peterhouse_shield.svg.png.webp) Queens'

Queens' Robinson

Robinson Selwyn

Selwyn Sidney Sussex

Sidney Sussex St Catharine's

St Catharine's St Edmund's

St Edmund's St John's

St John's_shield.svg.png.webp) Trinity

Trinity Trinity Hall

Trinity Hall Wolfson

Wolfson

Schools, faculties and departments

In addition to the 31 colleges, the university is made up of over 150 departments, faculties, schools, syndicates and other institutions.[72] Members of these are usually also members of one of the colleges and responsibility for running the entire academic programme of the university is divided among them. The university also has a centre for part-time study, the Institute of Continuing Education, which is housed in Madingley Hall, a 16th-century manor house in Cambridgeshire.

A "School" in the University of Cambridge is a broad administrative grouping of related faculties and other units. Each has an elected supervisory body—the "Council" of the school—comprising representatives of the constituent bodies. There are six schools:[73]

- Arts and Humanities

- Biological Sciences

- Clinical Medicine

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Physical Sciences

- Technology

Teaching and research in Cambridge is organised by faculties. The faculties have different organisational sub-structures which partly reflect their history and partly their operational needs, which may include a number of departments and other institutions. In addition, a small number of bodies called 'Syndicates' have responsibilities for teaching and research, e.g. Cambridge Assessment, the University Press, and the University Library.

Chancellor and Vice-Chancellor

The office of Chancellor of the university, for which there are no term limits, is mainly ceremonial and is held by David Sainsbury, Baron Sainsbury of Turville, following the retirement of the Duke of Edinburgh on his 90th birthday in June 2011. Lord Sainsbury was nominated by the official Nomination Board to succeed him,[74] and Abdul Arain, owner of a local grocery store, Brian Blessed and Michael Mansfield were also nominated.[75][76][77] The election took place on 14 and 15 October 2011.[77] David Sainsbury won the election taking 2,893 of the 5,888 votes cast, winning on the first count.

The current Vice-Chancellor is Stephen Toope.[78] While the Chancellor's office is ceremonial, the Vice-Chancellor is the de facto principal administrative officer of the university. The university's internal governance is carried out almost entirely by its own members,[79] with very little external representation on its governing body, the Regent House (though there is external representation on the Audit Committee, and there are four external members on the University's Council, who are the only external members of the Regent House).[80]

Senate and the Regent House

The Senate consists of all holders of the MA degree or higher degrees. It elects the Chancellor and the High Steward, and elected two members of the House of Commons until the Cambridge University constituency was abolished in 1950. Prior to 1926, it was the university's governing body, fulfilling the functions that the Regent House fulfils today.[81] The Regent House is the university's governing body, a direct democracy comprising all resident senior members of the University and the Colleges, together with the Chancellor, the High Steward, the Deputy High Steward, and the Commissary.[82] The public representatives of the Regent House are the two Proctors, elected to serve for one year, on the nomination of the Colleges.

Council and the General Board

Although the University Council is the principal executive and policy-making body of the university, it must report and be accountable to the Regent House through a variety of checks and balances. It has the right of reporting to the university, and is obliged to advise the Regent House on matters of general concern to the university. It does both of these by causing notices to be published by authority in the Cambridge University Reporter, the official journal of the university. Since January 2005, the membership of the council has included two external members,[83] and the Regent House voted for an increase from two to four in the number of external members in March 2008,[84][85] and this was approved by Her Majesty the Queen in July 2008.[86]

The General Board of the Faculties is responsible for the academic and educational policy of the university,[87] and is accountable to the council for its management of these affairs.

Faculty Boards are responsible to the General Board; other Boards and Syndicates are responsible either to the General Board (if primarily for academic purposes) or to the council. In this way, the various arms of the university are kept under the supervision of the central administration, and thus the Regent House.

Benefactions and fundraising

In 2000, Bill Gates of Microsoft donated US$210 million through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to endow the Gates Scholarships for students from outside the UK seeking postgraduate study at Cambridge.[88]

In the fiscal year ending 31 July 2019, the central university, excluding colleges, had a total income of £2.192 billion, of which £592.4 million was from research grants and contracts.[89]

Over the past decade to 2019, Cambridge has received an average of £271m a year in philanthropic donations.[90]

The 'Stormzy Scholarship for Black UK Students' covers tuition costs for two students and maintenance grants for up to four years.[91][92]

Bonds

The University of Cambridge borrowed £350 million by issuing a 40-year security bond in October 2012.[93] Its interest rate is about 0.6 percent higher than a British government 40-year bond. Vice-Chancellor Leszek Borysiewicz hailed the success of the issue.[94] In a 2010 report, the Russell Group of 20 leading universities made a conclusion that higher education could be financed by issuing bonds.[93]

Affiliations and memberships

Cambridge is a member of the Russell Group of research-led British universities, the G5, the League of European Research Universities, and the International Alliance of Research Universities, and forms part of the "golden triangle" of research intensive and southern English universities.[95] It is also closely linked with the development of the high-tech business cluster known as "Silicon Fen", and as part of the Cambridge University Health Partners, an academic health science centre.

Academic profile

Admissions

| 2019[96] | 2018[97] | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications[98] | 19,359 | 18,378 | 17,235 | 16,795 | 16,505 | 16,970 | 16,330 |

| Offer Rate (%)[99] | 24.3 | 24.8 | 31.2 | 33.8 | 33.5 | 32.5 | 32.2 |

| Enrols[100] | 3,528 | 3,465 | 3,480 | 3,440 | 3,430 | 3,425 | 3,355 |

| Yield (%) | 75.2 | 76.0 | 64.7 | 60.6 | 62.0 | 62.1 | 63.8 |

| Applicant/Enrolled Ratio | 5.49 | 5.30 | 4.95 | 4.88 | 4.81 | 4.95 | 4.87 |

| Average Entry Tariff[101][note 1] | n/a | n/a | n/a | 226 | 592 | 600 | 601 |

Procedure

Undergraduate applications to Cambridge must be made through UCAS in time for the early deadline, currently mid-October in the year before starting. Until the 1980s candidates for all subjects were required to sit special entrance examinations,[102] since replaced by additional tests for some subjects, such as the Thinking Skills Assessment and the Cambridge Law Test.[103] The university is considering reintroducing an admissions exam for all subjects with effect from 2016.[104] The university gave offers of admission to 33.5% of its applicants in 2016, the 2nd lowest amongst the Russell Group, behind Oxford.[105] The acceptance rate for students in the 2018–2019 cycle was 18.8%.[106][107] In 2021, Cambridge introduced an 'over-subscription' clause to its offers, which allows it to withdraw places if too many students meet its entrance criteria. The clause can be invoked in the event of 'circumstances outside the reasonable control of the university. It was introduced due to a record number of A-level pupils getting the highest grades from teacher assessment, which was introduced due to the cancellation of A-levels in the COVID-19 pandemic.[108][109]

Most applicants who are called for interview will have been predicted at least three A-grade A-level qualifications relevant to their chosen undergraduate course, or the equivalent in other qualifications, such as getting at least 7,7,6 for higher-level subjects at IB. The A* A-level grade (introduced in 2010) now plays a part in the acceptance of applications, with the university's standard offer for most courses being set at A*AA,[110][111] with A*A*A for sciences courses. Due to a high proportion of applicants receiving the highest school grades, the interview process is needed for distinguishing between the most able candidates. The interview is performed by College Fellows, who evaluate candidates on unexamined factors such as potential for original thinking and creativity.[112] For exceptional candidates, a Matriculation Offer was sometimes previously offered, requiring only two A-levels at grade E or above. In 2006, 5,228 students who were rejected went on to get 3 A levels or more at grade A, representing about 63% of all applicants rejected.[113] The Sutton Trust maintains that Oxford University and Cambridge University recruit disproportionately from 8 schools which accounted for 1,310 Oxbridge places during three years, contrasted with 1,220 from 2,900 other schools.[114]

Strong applicants who are not successful at their chosen college may be placed in the Winter Pool, where they can be offered places by other colleges. This is in order to maintain consistency throughout the colleges, some of which receive more applicants than others.

Graduate admission is first decided by the faculty or department relating to the applicant's subject. When an offer is made, this effectively guarantees admission to a college—though not necessarily the applicant's preferred choice.[115]

Access

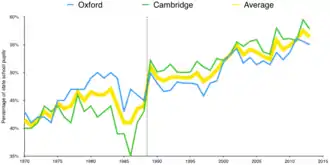

Public debate in the United Kingdom continues over whether admissions processes at Oxford and Cambridge are entirely merit based and fair; whether enough students from state schools are encouraged to apply to Cambridge; and whether these students succeed in gaining entry. In 2007–08, 57% of all successful applicants were from state schools[118] (roughly 93 percent of all students in the UK attend state schools). Critics have argued that the lack of state school applicants with the required grades applying to Cambridge and Oxford has had a negative impact on Oxbridge's reputation for many years, and the university has encouraged pupils from state schools to apply for Cambridge to help redress the imbalance.[119] Others counter that government pressure to increase state school admissions constitutes inappropriate social engineering.[120][121] The proportion of undergraduates drawn from independent schools has dropped over the years, and such applicants now form a (very large) minority (43%)[118][122] of the intake. In 2005, 32% of the 3599 applicants from independent schools were admitted to Cambridge, as opposed to 24% of the 6674 applications from state schools.[123] In 2008 the University of Cambridge received a gift of £4m to improve its accessibility to candidates from maintained schools.[124] Cambridge, together with Oxford and Durham, is among those universities that have adopted formulae that gives a rating to the GCSE performance of every school in the country to "weight" the scores of university applicants.[125]

With the release of admissions figures, a 2013 article in The Guardian reported that ethnic minority candidates had lower success rates in individual subjects even when they had the same grades as white applicants. The university was hence criticised for what was seen as institutional discrimination against ethnic minority applicants in favour of white applicants. The university denied the claims of institutional discrimination by stating the figures did not take into account "other variables".[126] A following article stated that in the years 2010–2012 ethnic minority applicants to medicine with 3 A* grades or higher were 20% less likely to gain admission than white applicants with similar grades. The University refused to provide figures for a wider range of subjects claiming it would be too costly.[127]

There are a number of educational consultancies that offer support with the applications process. Some make claims of improved chances of admission but these claims are not independently verified. None of these companies are affiliated to or endorsed by the University of Cambridge. The university informs applicants that all important information regarding the application process is public knowledge and none of these services is providing any inside information.[128]

Cambridge University has been criticised because many colleges admit a low proportion of black students though many apply. Of the 31 colleges at Cambridge 6 admitted fewer than 10 black or mixed race students from 2012 to 2016.[129]

Teaching

The academic year is divided into three academic terms, determined by the Statutes of the University.[130] Michaelmas term lasts from October to December; Lent term from January to March; and Easter term from April to June.

Within these terms undergraduate teaching takes place within eight-week periods called Full Terms. According to the university statutes, it is a requirement that during this period all students should live within 3 miles of the Church of St Mary the Great; this is defined as Keeping term. Students can graduate only if they fulfill this condition for nine terms (three years) when obtaining a Bachelor of Arts or twelve terms (four years) when studying for a Master of Science, Engineering or Mathematics.[131]

These terms are shorter than those of many other British universities.[132] Undergraduates are also expected to prepare heavily in the three holidays (known as the Christmas, Easter and Long Vacations).

Triposes involve a mixture of lectures (organised by the university departments), and supervisions (organised by the colleges). Science subjects also involve laboratory sessions, organised by the departments. The relative importance of these methods of teaching varies according to the needs of the subject. Supervisions are typically weekly hour-long sessions in which small groups of students (usually between one and three) meet with a member of the teaching staff or with a doctoral student. Students are normally required to complete an assignment in advance of the supervision, which they will discuss with the supervisor during the session, along with any concerns or difficulties they have had with the material presented in that week's lectures. The assignment is often an essay on a subject set by the supervisor, or a problem sheet set by the lecturer. Depending on the subject and college, students might receive between one and four supervisions per week.[133] This pedagogical system is often cited as being unique to Oxford (where "supervisions" are known as "tutorials")[134] and Cambridge.

A tutor named William Farish developed the concept of grading students' work quantitatively at the University of Cambridge in 1792.[135]

Research

The University of Cambridge has research departments and teaching faculties in most academic disciplines. All research and lectures are conducted by university departments. The colleges are in charge of giving or arranging most supervisions, student accommodation, and funding most extracurricular activities. During the 1990s Cambridge added a substantial number of new specialist research laboratories on several sites around the city, and major expansion continues on a number of sites.[136]

Cambridge also has a research partnership with MIT in the United States: the Cambridge–MIT Institute.

Graduation

Unlike in most universities, the Cambridge Master of Arts is not awarded by merit of study, but by right, four years after being awarded the BA.

At the University of Cambridge, each graduation is a separate act of the university's governing body, the Regent House, and must be voted on as with any other act. A formal meeting of the Regent House, known as a Congregation, is held for this purpose.[137] This is the common last act at which all the different university procedures (for: undergraduate and graduate students; and the different degrees) land. After degrees are approved, to have them conferred candidates must ask their Colleges to be presented during a Congregation.

Graduates receiving an undergraduate degree wear the academic dress that they were entitled to before graduating: for example, most students becoming Bachelors of Arts wear undergraduate gowns and not BA gowns. Graduates receiving a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD or Master's) wear the academic dress that they were entitled to before graduating, only if their first degree was also from the University of Cambridge; if their first degree is from another university, they wear the academic dress of the degree that they are about to receive, the BA gown without the strings if they are under 24 years of age, or the MA gown without strings if they are 24 and over.[138] Graduates are presented in the Senate House college by college, in order of foundation or recognition by the university, except for the royal colleges.

During the congregation, graduands are brought forth by the Praelector of their college, who takes them by the right hand, and presents them to the vice-chancellor for the degree they are about to take. The Praelector presents graduands with the following Latin statement (the following forms were used when the vice-chancellor was female), substituting "____" with the name of the degree:

"Dignissima domina, Domina Procancellaria et tota Academia praesento vobis hunc virum quem scio tam moribus quam doctrina esse idoneum ad gradum assequendum _____; idque tibi fide mea praesto totique Academiae.

(Most worthy Vice-Chancellor and the whole University, I present to you this man whom I know to be suitable as much by character as by learning to proceed to the degree of ____; for which I pledge my faith to you and to the whole University.)"

and female graduands with the following:

"Dignissima domina, Domina Procancellaria et tota Academia praesento vobis hanc mulierem quam scio tam moribus quam doctrina esse idoneam ad gradum assequendum ____; idque tibi fide mea praesto totique Academiae.

(Most worthy Vice-Chancellor and the whole University, I present to you this woman whom I know to be suitable as much by character as by learning to proceed to the degree of ____; for which I pledge my faith to you and to the whole University.)"

After presentation, the graduand is called by name and kneels before the vice-chancellor and proffers their hands to the vice-chancellor, who clasps them and then confers the degree through the following Latin statement—the Trinitarian formula (in nomine Patris...) may be omitted at the request of the graduand:

"Auctoritate mihi commissa admitto te ad gradum ____, in nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti.

(By the authority committed to me, I admit you to the degree of ____, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.)"

The now-graduate then rises, bows and leaves the Senate House through the Doctor's door, where he or she receives his or her certificate, into Senate House Passage.[137]

Libraries and museums

The university has 116 libraries.[139] The Cambridge University Library is the central research library, which holds over 8 million volumes. It is a legal deposit library, therefore it is entitled to request a free copy of every book published in the UK and Ireland.[140] In addition to the University Library and its dependents, almost every faculty or department has a specialised library; for example, the History Faculty's Seeley Historical Library possesses more than 100,000 books. Furthermore, every college has a library as well, partially for the purposes of undergraduate teaching, and the older colleges often possess many early books and manuscripts in a separate library. For example, Trinity College's Wren Library has more than 200,000 books printed before 1800, while Corpus Christi College's Parker Library possesses one of the greatest collections of medieval manuscripts in the world, with over 600 manuscripts.

Cambridge University operates eight arts, cultural, and scientific museums, and a botanic garden.[141] The Fitzwilliam Museum, is the art and antiquities museum, the Kettle's Yard is a contemporary art gallery, the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology houses the university's collections of local antiquities, together with archaeological and ethnographic artefacts from around the world, the Cambridge University Museum of Zoology houses a wide range of zoological specimens from around the world and is known for its iconic finback whale skeleton that hangs outside. This Museum also has specimens collected by Charles Darwin. Other museums include, the Museum of Classical Archaeology, the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences which is the geology museum of the university, the Polar Museum, part of the Scott Polar Research Institute which is dedicated to Captain Scott and his men, and focuses on the exploration of the Polar Regions.

The Cambridge University Botanic Garden is the botanic garden of the university, created in 1831.

Publishing and assessments

The university's publishing arm, the Cambridge University Press, is the oldest printer and publisher in the world, and it is the second largest university press in the world.[142][143]

The university set up its Local Examination Syndicate in 1858. Today, the syndicate, which is known as Cambridge Assessment, is Europe's largest assessment agency and it plays a leading role in researching, developing and delivering assessments across the globe.[144]

Reputation and rankings

| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2021)[145] | 1 |

| Guardian (2021)[146] | 3 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2021)[147] | 1 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2020)[148] | 3 |

| QS (2021)[149] | 7 |

| THE (2021)[150] | 6 |

| British Government assessment | |

| Teaching Excellence Framework[151] | Gold |

In 2011, Times Higher Education (THE) recognised Cambridge as one of the world's "six super brands" on its World Reputation Rankings, along with Berkeley, Harvard, MIT, Oxford and Stanford.[152] As of September 2017, Cambridge is recognised by THE as the world's second best university.[153]

According to the 2016 Complete University Guide, the University of Cambridge is ranked first amongst the UK's universities; this ranking is based on a broad raft of criteria from entry standards and student satisfaction to quality of teaching in specific subjects and job prospects for graduates.[154] The University is ranked as the 2nd best university in the UK for the quality of graduates according to recruiters from the UK's major companies.[155]

In 2014–15, according to University Ranking by Academic Performance (URAP), Cambridge is ranked second in UK (coming second to Oxford) and ranked fifth in the world.[156]

In the 2001 and 2008 Government Research Assessment Exercises, Cambridge was ranked first in the country.[157] In 2005, it was reported that Cambridge produces more PhDs per year than any other British university (over 30% more than second placed Oxford).[158] In 2006, a Thomson Scientific study showed that Cambridge has the highest research paper output of any British university, and is also the top research producer (as assessed by total paper citation count) in 10 out of 21 major British research fields analysed.[159] Another study published the same year by Evidence showed that Cambridge won a larger proportion (6.6%) of total British research grants and contracts than any other university (coming first in three out of four broad discipline fields).[160] The university is also closely linked with the development of the high-tech business cluster in and around Cambridge, which forms the area known as Silicon Fen or sometimes the "Cambridge Phenomenon". In 2004, it was reported that Silicon Fen was the second largest venture capital market in the world, after Silicon Valley. Estimates reported in February 2006 suggest that there were about 250 active startup companies directly linked with the university, worth around US$6 billion.[161]

Cambridge has been highly ranked by most international and UK league tables. In particular, it had topped the QS World University Rankings from 2010/11 to 2011/12.[162][163] A 2006 Newsweek overall ranking, which combined elements of the THES-QS and ARWU rankings with other factors that purportedly evaluated an institution's global "openness and diversity", suggested Cambridge was sixth around the globe.[164] In The Guardian newspaper's 2012 rankings, Cambridge had overtaken Oxford in philosophy, law, politics, theology, maths, classics, anthropology and modern languages.[165] In the 2009 Times Good University Guide Subject Rankings, it was ranked top (or joint top) in 34 out of the 42 subjects which it offers.[166] But Cambridge has been ranked only 30th in the world and 3rd in the UK by the Mines ParisTech: Professional Ranking of World Universities based on the number of alumni holding CEO position in Fortune Global 500 companies.

Sexual harassment

In recent years, Cambridge has come under increased criticism and legal challenges for its mishandling of sexual harassment claims.[167][168] In 2019, for example, former student Danielle Bradford sued Cambridge through noted sexual harassment lawyer Ann Olivarius for how the university handled her complaint of sexual misconduct. "I was told that I should think about it very carefully because making a complaint could affect my place in my department."[169] In 2020, hundreds of current and former students accused the university in a letter of “a complete failure” to deal with complaints of sexual misconduct.[170]

Student life

Student Unions

There are two Student Unions in Cambridge: CUSU (the Cambridge University Students‘ Union) and the GU (the Graduate Union). CUSU represents all University students, and the GU solely represents graduate students. All students are automatically members of either CUSU or both CUSU and GU, depending on their course of study.[171][172]

CUSU was founded in 1964 as the Students' Representative Council (SRC); the six most important positions in the Union are occupied by sabbatical officers.[173] However, turnout in recent elections has been low, with the 2014/15 president elected with votes in favour from only 7.5% of the whole student body.[174]

Sport

Rowing is a particularly popular sport at Cambridge, and there are competitions between colleges, notably the bumps races, and against Oxford, the Boat Race. There are also Varsity matches against Oxford in many other sports, ranging from cricket and rugby, to chess and tiddlywinks. Athletes representing the university in certain sports are entitled to apply for a Cambridge Blue at the discretion of the Blues Committee, consisting of the captains of the thirteen most prestigious sports. There is also the self-described "unashamedly elite" Hawks' Club, which is for men only, whose membership is usually restricted to Cambridge Full Blues and Half Blues.[175] The Ospreys are the equivalent female club.

The University of Cambridge Sports Centre opened in August 2013. Phase 1 included a 37x34m Sports Hall, a Fitness Suite, a Strength and Conditioning Room, a Multi-Purpose Room and Eton and Rugby Fives courts. Phase 1b included 5 glass backed squash courts and a Team Training Room. Future phases include indoor and outdoor tennis courts and a swimming pool.[176]

The university also has an Athletics Track at Wilberforce Road, an Indoor Cricket School and Fenner's Cricket Ground.

Societies

Numerous student-run societies exist in order to encourage people who share a common passion or interest to periodically meet or discuss. As of 2010, there were 751 registered societies.[177] In addition to these, individual colleges often promote their own societies and sports teams.

Although technically independent from the university, the Cambridge Union serves as a focus for debating and public speaking, as the oldest free speech society in the world, and the largest in Cambridge. Drama societies notably include the Amateur Dramatic Club (ADC) and the comedy club Footlights, which are known for producing well-known show-business personalities. The Cambridge University Chamber Orchestra explores a range of programmes, from popular symphonies to lesser known works; membership of the orchestra is composed of students of the university.

Newspapers and radio

Cambridge's oldest student newspaper is Varsity. Established in 1947, notable figures to have edited the paper include Jeremy Paxman, BBC media editor Amol Rajan, and Vogue international editor Suzy Menkes. It has also featured the early writings of Zadie Smith (who appeared in Varsity's literary anthology offshoot, The Mays), Robert Webb, Tristram Hunt, and Tony Wilson.

With a print run of 9,000, Varsity is the only student paper to go to print on a weekly basis. News stories from the paper have recently appeared in The Guardian, The Times, The Sunday Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Independent, and The i.

Other student publications include The Cambridge Student, which is funded by Cambridge University Students' Union and goes to print on a fortnightly basis, and The Tab. Founded by two Cambridge students in 2009, The Tab is online-only (apart from one print edition in Freshers' Week), and mostly features light-hearted features content.

The Mays is a literary anthology made up of student prose, poetry, and visual art from both Cambridge and Oxford. Founded in 1992 by three Cambridge students, the anthology goes to print on an annual basis. It is overseen by Varsity Publications Ltd, the same body that is responsible for Varsity, the newspaper.

There are many other journals, magazines, and zines. Another literary journal, Notes, is published roughly two times per term. Many colleges also have their own publications run by students.

The student radio station, Cam FM, is run together with students from Anglia Ruskin university. One of few student radio stations to have an FM licence (frequency 97.2 MHz), the station hosts a mixture of music, talk, and sports shows.

JCR and MCR

In addition to university-wide representation, students can benefit from their own college student unions, which are known as JCR (Junior Combination Room) for undergraduates and MCR (Middle Combination Room) for postgraduates. These serve as a link between college staff and members and consists of officers elected annually between the fellow students; individual JCR and MCRs also report to CUSU, which offers training courses for some of the positions within the body.[178]

Formal Halls and May Balls

One privilege of student life at Cambridge is the opportunity to attend formal dinners at college. These are called Formal Hall and occur regularly during term time. Students sit down for a meal in their gowns, while Fellows eat separately at High Table: the beginning and end of the function is usually marked with a grace said in Latin. Special Formal Halls are organised for events such as Christmas and the Commemoration of Benefactors.[179]

After the exam period, May Week is held and it is customary to celebrate by attending May Balls. These are all-night long lavish parties held in the colleges where food and drinks are served and entertainment is provided. Time magazine argues that some of the larger May Balls are among the best private parties in the world. Suicide Sunday, the first day of May Week, is a popular date for organising garden parties.[180]

Notable alumni and academics

Over the course of its history, a number of Cambridge University academics and alumni have become notable in their fields, both academic and in the wider world. As of October 2020, 121 affiliates of the University of Cambridge have won 122 Nobel prizes (Frederick Sanger won twice[181][182]), with 70 former students of the university having won the prize. In addition, as of 2019, Cambridge alumni, faculty members and researchers have won 11 Fields Medals and 7 Turing Awards.

Mathematics and sciences

.png.webp)

Among the most famous of Cambridge natural philosophers is Sir Isaac Newton, who conducted many of his experiments in the grounds of Trinity College. Others are Sir Francis Bacon, who was responsible for the development of the scientific method and the mathematicians John Dee and Brook Taylor. Pure mathematicians include G. H. Hardy, John Edensor Littlewood, Mary Cartwright and Augustus De Morgan; Sir Michael Atiyah, a specialist in geometry; William Oughtred, inventor of the logarithmic scale; John Wallis, first to state the law of acceleration; Srinivasa Ramanujan, the self-taught genius who made substantial contributions to mathematical analysis, number theory, infinite series and continued fractions; and James Clerk Maxwell, who brought about the "second great unification of physics" (the first being accredited to Newton) with his classical theory of electromagnetic radiation. In 1890, mathematician Philippa Fawcett was the person with the highest score in the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos exams, but as a woman was unable to take the title of 'Senior Wrangler'.

In biology, Charles Darwin, famous for developing the theory of natural selection, was an alumnus of Christ's College, although his education was intended to allow him to become a clergyman. Biologists Francis Crick and James Watson worked out a model for the three-dimensional structure of DNA while working at the Cavendish Laboratory; Cambridge graduates Maurice Wilkins and especially Rosalind Franklin produced key X-ray crystallography data, which was shared with Watson by Wilkins. Wilkins went on to help verify the proposed structure and win the Nobel Prize with Watson and Crick. More recently, Sir Ian Wilmut was part of the team responsible for the first cloning of a mammal (Dolly the Sheep in 1996), naturalist and broadcaster David Attenborough, ethologist Jane Goodall, expert on chimpanzees was a PhD student, anthropologist Dame Alison Richard, former vice-chancellor of the university, and Frederick Sanger, a biochemist known for developing Sanger sequencing and receiving two Nobel prizes.

Despite the university's delay in admitting women to full degrees, Cambridge women were at the heart of scientific research throughout the 20th century. Notable female scientists include; biochemist Marjory Stephenson, plant physiologist Gabrielle Howard, social anthropologist Audrey Richards, psycho-analyst Alix Strachey, who with her husband translated the works of Sigmund Freud, Kavli Prize-winner Brenda Milner, co-discovery of specialised brain networks for memory and cognition. Veterinary epidemiologist Sarah Cleaveland has worked to eliminate rabies in the Serengeti.[183]

The university can be considered the birthplace of the computer, mathematician and "father of the computer" Charles Babbage designed the world's first computing system as early as the mid-1800s. Alan Turing went on to devise what is essentially the basis for modern computing and Maurice Wilkes later created the first programmable computer. The webcam was also invented at Cambridge University, showing the Trojan Room coffee pot in the Computer Laboratories.

In physics, Ernest Rutherford who is regarded as the father of nuclear physics, spent much of his life at the university where he worked closely with E. J. Williams and Niels Bohr, a major contributor to the understanding of the atom, J. J. Thomson, discoverer of the electron, Sir James Chadwick, discoverer of the neutron, and Sir John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, responsible for first splitting the atom. J. Robert Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb, also studied under Rutherford and Thomson. Joan Curran devised the 'chaff' technique during the Second World War to disrupt radar on enemy planes.

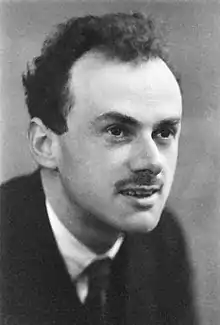

Astronomers Sir John Herschel, Sir Arthur Eddington, Paul Dirac, the discoverer of antimatter and one of the pioneers of quantum mechanics; Stephen Hawking, theoretical physicist and the university's long-serving Lucasian Professor of Mathematics until 2009; and Lord Martin Rees, the current Astronomer Royal and former Master of Trinity College. John Polkinghorne, a mathematician before his entrance into the Anglican ministry, received the Templeton Prize for his work reconciling science and religion.

Other significant scientists include Henry Cavendish, the discoverer of hydrogen; Frank Whittle, co-inventor of the jet engine; William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), who formulated the original Laws of Thermodynamics; William Fox Talbot, who invented the camera, Alfred North Whitehead, Einstein's major opponent; Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, one of the fathers of radio science; Lord Rayleigh, who made extensive contributions to both theoretical and experimental physics in the 20th century; and Georges Lemaître, who first proposed a Big Bang theory.

Humanities, music and art

In the humanities, Greek studies were inaugurated at Cambridge in the early sixteenth century by Desiderius Erasmus; contributions to the field were made by Richard Bentley and Richard Porson. John Chadwick was associated with Michael Ventris in the decipherment of Linear B. The Latinist A. E. Housman taught at Cambridge but is more widely known as a poet. Simon Ockley made a significant contribution to Arabic Studies.

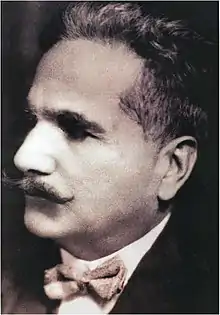

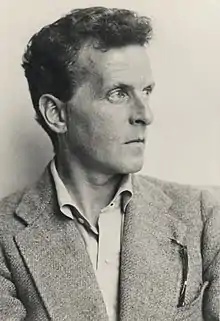

Distinguished Cambridge academics include economists such as John Maynard Keynes, Thomas Malthus, Alfred Marshall, Milton Friedman, Joan Robinson, Piero Sraffa, Ha-Joon Chang and Amartya Sen, a former Master of Trinity College. Philosophers Sir Francis Bacon, Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Leo Strauss, George Santayana, G. E. M. Anscombe, Sir Karl Popper, Sir Bernard Williams, Sir Allama Muhammad Iqbal and G. E. Moore were all Cambridge scholars, as were historians such as Thomas Babington Macaulay, Frederic William Maitland, Lord Acton, Joseph Needham, E. H. Carr, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Rhoda Dorsey, E. P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, Quentin Skinner, Niall Ferguson and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., and famous lawyers such as Glanville Williams, Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, and Sir Edward Coke.

Religious figures have included Rowan Williams, former archbishop of Canterbury and his predecessors; William Tyndale, the biblical translator; Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, and Nicholas Ridley, known as the "Oxford martyrs" from the place of their execution; Benjamin Whichcote and the Cambridge Platonists; William Paley, the Christian philosopher known primarily for formulating the teleological argument for the existence of God; William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson, largely responsible for the abolition of the slave trade; Evangelical churchman Charles Simeon; John William Colenso, the bishop of Natal who developed views on the interpretation of Scripture and relations with native peoples that seemed dangerously radical at the time; John Bainbridge Webster and David F. Ford, theologians; and six winners of the Templeton Prize, the highest accolade for the study of religion since its foundation in 1972.

Composers Ralph Vaughan Williams, Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, William Sterndale Bennett, Orlando Gibbons and, more recently, Alexander Goehr, Thomas Adès, John Rutter, Julian Anderson and Judith Weir were all at Cambridge. The university has also produced instrumentalists and conductors, including Colin Davis, John Eliot Gardiner, Roger Norrington, Trevor Pinnock, Andrew Manze, Richard Egarr, Mark Elder, Richard Hickox, Christopher Hogwood, Andrew Marriner, David Munrow, Simon Standage, Endellion Quartet and Fitzwilliam Quartet. Although known primarily for its choral music, the university has also produced members of contemporary bands such as Radiohead, Hot Chip, Procol Harum, Clean Bandit, Sports Team songwriter and entertainer Jonathan King, Henry Cow, and the singer-songwriter Nick Drake.

Artists Quentin Blake, Roger Fry, Rose Ferraby and Julian Trevelyan, sculptors Antony Gormley, Marc Quinn and Sir Anthony Caro, and photographers Antony Armstrong-Jones, Sir Cecil Beaton and Mick Rock all attended as undergraduates.

Literature

Writers to have studied at the university include the Elizabethan dramatist Christopher Marlowe, his fellow University Wits Thomas Nashe and Robert Greene, arguably the first professional authors in England, and John Fletcher, who collaborated with Shakespeare on The Two Noble Kinsmen, Henry VIII and the lost Cardenio and succeeded him as house playwright of The King's Men. Samuel Pepys matriculated in 1650, known for his diary, the original manuscripts of which are now housed in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College. Lawrence Sterne, whose novel Tristram Shandy is judged to have inspired many modern narrative devices and styles. In the following century, the novelists W. M. Thackeray, best known for Vanity Fair, Charles Kingsley, author of Westward Ho! and Water Babies, and Samuel Butler, remembered for The Way of All Flesh and Erewhon, were all at Cambridge.

Ghost story writer M. R. James served as provost of King's College from 1905 to 1918. Novelist Amy Levy was the first Jewish woman to attend the university. Modernist writers to have attended the university include E. M. Forster, Rosamond Lehmann, Vladimir Nabokov, Christopher Isherwood and Malcolm Lowry. Although not a student, Virginia Woolf wrote her essay A Room of One's Own while in residence at Newnham College. Playwright J. B. Priestley, physicist and novelist C. P. Snow and children's writer A. A. Milne were also among those who passed through the university in the early 20th century. They were followed by the postmodernists Patrick White, J. G. Ballard, and the early postcolonial writer E. R. Braithwaite. More recently, alumni include comedy writers Douglas Adams, Tom Sharpe and Howard Jacobson, the popular novelists A. S. Byatt, Sir Salman Rushdie, Nick Hornby, Zadie Smith, Louise Dean, Robert Harris and Sebastian Faulks, the action writers Michael Crichton, David Gibbins and Jin Yong, and contemporary playwrights and screenwriters such as Julian Fellowes, Stephen Poliakoff, Michael Frayn and Sir Peter Shaffer.

Cambridge poets include Edmund Spenser, author of The Faerie Queene, the Metaphysical poets John Donne, George Herbert and Andrew Marvell, John Milton, renowned for his late epic Paradise Lost, the Restoration poet and playwright John Dryden, the pre-romantic Thomas Gray, best known his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose joint work Lyrical Ballads is often seen to mark the beginning of the Romantic movement, later Romantics such as Lord Byron and the postromantic Alfred, Lord Tennyson, authors of the best known carpe diem poems including Robert Herrick best known "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time" with the first line "Gather ye rosebuds while ye may" and Andrew Marvell who authored "To His Coy Mistress", classical scholar and lyric poet A. E. Housman, war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Rupert Brooke, modernist T. E. Hulme, confessional poets Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath and John Berryman, and, more recently, Cecil Day-Lewis, Joseph Brodsky, Kathleen Raine and Geoffrey Hill. At least nine of the Poets Laureate graduated from Cambridge. The university has also made a notable contribution to literary criticism, having produced, among others, F. R. Leavis, I. A. Richards, C. K. Ogden and William Empson, often collectively known as the Cambridge Critics, the Marxists Raymond Williams, sometimes regarded as the founding father of cultural studies, and Terry Eagleton, author of Literary Theory: An Introduction, the most successful academic book ever published, the Aesthetician Harold Bloom, the New Historicist Stephen Greenblatt, and biographical writers such as Lytton Strachey, a central figure in the Bloomsbury Group, Peter Ackroyd and Claire Tomalin.

Actors and directors such as Sir Ian McKellen, Eleanor Bron, Miriam Margolyes, Sir Derek Jacobi, Sir Michael Redgrave, James Mason, Emma Thompson, Stephen Fry, Hugh Laurie, John Cleese, John Oliver, Freddie Highmore, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman, Graeme Garden, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Bill Oddie, Simon Russell Beale, Tilda Swinton, Thandie Newton, Georgie Henley, Rachel Weisz, Sacha Baron Cohen, Tom Hiddleston, Sara Mohr-Pietsch, Eddie Redmayne, Dan Stevens, Jamie Bamber, Lily Cole, David Mitchell, Robert Webb, Richard Ayoade, Mel Giedroyc and Sue Perkins all studied at the university, as did directors such as Mike Newell, Sam Mendes, Stephen Frears, Paul Greengrass, Chris Weitz and John Madden.

Sports

Athletes who are university graduates or attendees have won a total of 194 Olympic medals, including 88 gold.[18] The legendary Chinese six-time world table tennis champion Deng Yaping; the sprinter and athletics hero Harold Abrahams; the inventors of the modern game of football, H. de Winton and J. C. Thring; and George Mallory, the famed mountaineer all attended Cambridge.

Education

Notable educationalists to have attended the university include the founders and early professors of Harvard University, including John Harvard himself; Emily Davies, founder of Girton College, the first residential higher education institution for women, and John Haden Badley, founder of the first mixed-sex public school (i.e. not public) in England; Anil Kumar Gain, 20th century mathematician and founder of the Vidyasagar University in Bengal, and Menachem Ben-Sasson, Israeli President of Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Politics

Cambridge has a strong reputation in the fields of politics, having educated:[184]

- Fourteen British Prime Ministers, including Robert Walpole, considered to be the first Prime Minister of Great Britain.

- At least 30 foreign Heads of State/Government, including presidents of India, Ireland, Zambia, South Korea, Uganda and Trinidad and Tobago; along with Prime Ministers of India, Burma, Pakistan, South Africa, New Zealand, Poland, Australia, France, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Malta, Thailand, Malaysia, and Jordan.

- At least nine monarchs, including Edward VII, George VI, King Peter II of Yugoslavia, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and Queen Sofía of Spain. The university has also educated Charles, Prince of Wales and a large number of other royals.

- Three signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence (Thomas Lynch, Jr., Arthur Middleton, Thomas Nelson, Jr.).[185]

- Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England (1653–58).[186]

In literature and popular culture

Throughout its history, the university has featured in literature and artistic works by various authors.

Gallery

The Great Gate of Trinity College

The Great Gate of Trinity College Corpus Christi College New Court

Corpus Christi College New Court

.jpg.webp)

Bredon House of Wolfson College

Bredon House of Wolfson College St Edmund's College Norfolk Building

St Edmund's College Norfolk Building Downing College East Range

Downing College East Range Queens' College Old Gatehouse

Queens' College Old Gatehouse Selwyn College Chapel

Selwyn College Chapel

Selwyn College Old Court

Selwyn College Old Court Jesus College Chapel

Jesus College Chapel St John's College Great gate

St John's College Great gate The entrance of Trinity Hall

The entrance of Trinity Hall The Dining Hall at Selwyn College, Cambridge

The Dining Hall at Selwyn College, Cambridge The Cavendish Building of Homerton College, Cambridge

The Cavendish Building of Homerton College, Cambridge

The chapel, Sidney Sussex College

The chapel, Sidney Sussex College Judge Business School interior

Judge Business School interior The Grove at Fitzwilliam College

The Grove at Fitzwilliam College

See also

- Cambridge University Constabulary

- Cambridge University primates

- List of medieval universities

- List of Nobel laureates affiliated with the University of Cambridge

- List of organisations and institutions associated with the University of Cambridge

- List of organisations with a British royal charter

- List of professorships at the University of Cambridge

Notes

- New UCAS Tariff system from 2016

References

- Colleges of the University of Cambridge

- "Reports and Financial Statement 2019" (PDF). University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Colleges £4,101.2M,[1] University £3,020.0M[2]

- https://www.cam.ac.uk/system/files/reports_and_financial_statements_2019_final.pdf

- "Facts and Figures January 2018" (PDF). University of Cambridge. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- https://www.information-hub.admin.cam.ac.uk/university-profile/student-numbers/student-numbers-college

- "Estate Data". Estate Management. University of Cambridge. 28 November 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- "Identity Guidelines – Colour" (PDF). University of Cambridge Office of External Affairs and Communications. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- "Early records". University of Cambridge. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Sager, Peter (2005). Oxford and Cambridge: An Uncommon History.

- "A Brief History: Early records". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Adams, Richard; Greenwood, Xavier (28 May 2018). "Oxford and Cambridge university colleges hold £21bn in riches". The Guardian.

- https://www.cam.ac.uk/system/files/reports_and_financial_statements_2019_final.pdf

- Colleges of the University of Cambridge

- "REPORTS AND FINANCIAL STATEMENT 2019" (PDF). University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Colleges £7,424.3M,[14] University (consolidated) £5,144.8M[15]

- "Nobel prize winners". University of Cambridge. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "All Known Cambridge Olympians". Hawks Club. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Davies, Mark (4 November 2010). "'To lick a Lord and thrash a cad': Oxford 'Town & Gown'". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- Leedham-Green, Elisabeth (1996). A Concise History of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-521-43978-7. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "Middle Ages". British History Timeline. BBC. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- de Ridder-Symoens, Hilde (2003). Cambridge University Press (ed.). A History of the University in Europe: Universities in the Middle Ages. 1. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-521-54113-8.

- Hackett, M.B. (1970). The original statutes of Cambridge University: The text and its history. Cambridge University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-521-07076-8. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Willey, David (2012). "Vatican reveals Cambridge papers". Cam. 66: 5.

- Cooper, Charles Henry (1860). Memorials of Cambridge. 1. W. Metcalfe. p. 32. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- Helmholtz, R.H. (1990). Roman Canon Law in Reformation England. Cambridge Studies in English Legal History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 35, 153. ISBN 978-0-521-38191-8.

- Thompson, Roger, Mobility & Migration, East Anglian Founders of New England, 1629–1640, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994, 19.

- Forsyth, A. R. (1935). "Old Tripos days at Cambridge". The Mathematical Gazette. 19 (234): 162–179. doi:10.2307/3605871. JSTOR 3605871.

- "The History of Mathematics in Cambridge". Faculty of Mathematics, University of Cambridge. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- The six alumni are Michael Atiyah (Abel Prize and Fields Medal), Enrico Bombieri, Simon Donaldson, Richard Borcherds, Timothy Gowers, Alan Baker and the four official representatives were John G. Thompson, Alan Baker, Richard Borcherds, Timothy Gowers (see also "Fields Medal". Wolfram MathWorld. Retrieved 3 December 2009.)

- The National Archives (ed.). "Cambridge University Act 1856". Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- University of Cambridge, ed. (4 May 2010). "Biography – The Hon. Richard Fitzwilliam, 7th Viscount FitzWilliam". Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- Taylor 1994, p. 22

- Cambridge University Physics Society (1995). Cambridge University Physics Society (ed.). A Hundred Years and More of Cambridge Physics. ISBN 978-0-9507343-1-6.

- John Aldrich – "The Maths PhD in the UK: Notes on its History – Economics"

- University of Cambridge, ed. (28 January 2013). "The Revived University of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries". Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "A Brief History: The University after 1945". University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Chambers, Suzanna (31 May 1998). "At last, a degree of honour for 900 Cambridge women". The Independent. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "Trinity Hall's Steamboat Ladies". Trinity news. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- Martin, Nicole (8 June 2006). "St Hilda's to end 113-year ban on male students". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- "Single-sex colleges: a dying breed?". HERO. June 2007. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- "Special No 19". Cambridge University Reporter. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- "Choir that sings to the world". BBC. 24 December 2001. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- Baxter, Elizabeth (18 December 2009). "Carols from King's: Cambridge prepares for Christmas". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Cambridge City: Annual demographic and socio-economic report" (PDF). Cambridgeshire County Council. April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- "A brief history of Punting". Cambridge River Tour. Retrieved 4 September 2012.