Upper March

The Upper March (in Arabic: الثغر الأعلى, aṯ-Tagr al-A'la; in Spanish: Marca Superior) was an administrative and military division in northeast Al-Andalus, roughly corresponding to the Ebro valley and adjacent Mediterranean coast, from the 8th century to the early 11th century. It was established as a frontier province, or march, of the Emirate, later Caliphate of Córdoba, facing the Christian lands of the Carolingian Empire's Marca Hispanica, the Asturo-Leonese marches of Castile and Alava, and the nascent autonomous Pyrenean principalities. In 1018, the decline of the central Cordoban state allowed the lords of the Upper March to establish in its place the Taifa of Zaragoza.

Formation of the Upper March

In the half century after the initial Muslim invasion of the Iberian peninsula, much of the conquest and settlement was left to the local initiatives of clans and tribes in loose coalition rather than being a centrally coordinated scheme. As a result, the fertile lands of Septimania north of the Pyrenees were occupied, and held until 759, but any occupation of the uninviting lands of Galicia and Asturias was temporary and superficial.[1] Much of the land in the conquered areas had been owned by Christian landowners that resisted the invasion: this was confiscated and granted to the Arab and Berber troops that had participated in the invasion, with the Arabs tending to settle in the south, leaving the more remote and relatively barren areas to the Berbers. However, those Christian nobles and communities that had submitted were granted treaties that allowed them to retain their lands, on the payment of a significant annual tax for as long as they remained Christian.[1] The substantial advantages of conversion to Islam were supposed to have convinced Count Cassius, said to have been a count in the Ebro region in Visigoth times, and the reputed founder of the Banu Qasi (sometimes spelled Banu Casi) clan, to convert in 714. What is certain is that the existence of the Banu Qasi was recorded from 789, in the person of supposed grandson, Musa ibn Fortun ibn Qasi, and that the two most powerful local families in the Upper March in the late 8th and early 9th centuries, the Banu Qasi and the Banu Amrus were both native converts to Islam.[2]

Further Muslim expansion ended through the combined effects of a Berber Revolt in Iberia that commenced in 740 and, in the Middle East, the overthrow of the Umayyad Caliphate in the Abbasid Revolution of 747 to 750. The latter resulted in the creation of an Abbasid Caliphate that regarded al-Andalus as a rebel province needing to be recovered.[3] The Berber revolt led to the withdrawal of those Berbers who had been allocated land in the Duero valley, leaving few Muslims in the northwest of the peninsula.[3] Alfonso I, the Christian king of neighboring Asturias, which spanned the northern coast of Iberia from Galicia to the Basque territory, raided the former Berber lands and captured the cities of León, Astorga and Braga, killing their Muslim garrisons. Taking their populations north, he left the Duero valley a sparsely populated no man's land bordering what would become the Upper March to the west.[4] Meanwhile, in the north and east, the Frankish kingdom had extended their power into Aquitaine and, under Pepin the Strong had moved into Septimania in the 750s, capturing Narbonne in 759,[5] thus confining al-Andalus south of the Pyrenees. There was also a civil war fought in al-Andalus between the families deriving from northern and southern Arabia, leading in 747 to the ascendance of the Yemeni faction following the battle of Secunda (Sequnda, near Córdoba) and the installation at Zaragoza of a Yemeni, al-Sumayl ibn Hatim al-Kilabi, as governor over the northern Arab settlers of the Ebro valley. Two of their leaders, Amir al-Abdari and Hubab al-Zuhri, rebelled and besieged Zaragoza in 754. This rebellion was put down the next year by the army of Yusuf ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri, the governor of al-Andalus, and when a group of soldiers already suspected of being rebel sympathizers blocked him from executing the rebels, Yusuf sent them on a suicide mission against the Basques of Pamplona. These moves left southern Iberia exposed and enabled the fugitive Umayyad prince, Abd al-Rahman I, to cross from North Africa and gain a foothold, eventually leading to his conquest of al-Andalus and establishment of an independent Emirate of Córdoba.[6]

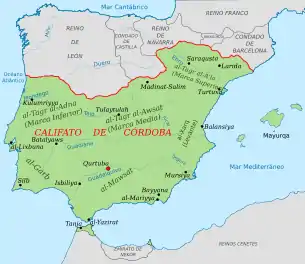

The strength of Abd al-Rahman's Umayyad Emirate lay in the Guadalquivir valley and to its south and east south and, rather than trying to conquer Christian lands or make their rulers accept Umayyad primacy, he and his successors concentrated on keeping the outlying areas of the Emirate under their control by setting-up three marches or thugur, (singular thagr). In the west was the Lower March (aṯ-Ṯaḡr al-Adna) based at Mérida, a Middle March (aṯ-Ṯaḡr al-Awsaṭ) ruled from Toledo and later Medinaceli, while in the east the Upper March had Zaragoza as its seat.[7] Each march was responsible for defending its area against Christian attack and supporting any major expeditions the Emirate's principal armies might make against the Christian territories.[2]

The Upper March consisted of several coras (territorial subdivisions, from the Arabic kura): Barbitaniya, stretching from the north of the present province of Huesca, with its capital in Barbastro,[8] and also including Boltaña, Alquézar, Naval, Salinas de Hoz, Olvena, and near the boundary of Muslim control, Graus, called Puertaspan (Puerto de Hispania, 'Gateway to al-Andalus');[9] Huesca (Washka), based in Huesca and including the fort of Bolea; Lleida, which included Mequinenza and Fraga; Zaragoza, both politically and economically the principal cora of the Upper March, centered on that city but also including Zuera, Ricla, Muel, Belchite, Alcañiz and Calanda; Calatayud, including its eponymous city as well as Maluenda and Daroca; Tudela, which included the cities of Tarazona and Borja and extended to the current La Rioja; and the smallest, Barusa, organized along the Rio Petri, with its capital in Molina de Aragón, and bordering Santaveria, in the Middle March. The northernmost of these coras, Barbitaniya and Huesca, formed a subdivision of the Upper March called the Distant or Farthest March (aṯ-Ṯaḡr al-‘Aqṣā).[7]

The Upper March was ruled by a Lord of the March (Sāhib aṯ-Ṯaḡr), named by the emir or caliph, who acted as civil governor (amil, wali) or military commander (qa'id), sometimes both. They in turn depended on the district governors, who were responsible for overseeing taxation, maintaining fortresses, defending their people, and accompanying the Córdoba emir or caliph on campaigns against the Christian states of the north.[10]

Failed Carolingian expansion

The nobility of the Upper March remained fractious. In 774, Husayn of Zaragoza rebelled against Umayyad Córdoba, proclaiming for the Abbasids, and the Emir sent an army to subjugate the march. Then in 778, Sulayman ibn Yaqdhan al Arabi of Barcelona sent envoys to Charlemagne, offering his fealty along with that of Abu Taur of Huesca and Husayn of Zaragoza in exchange for his support in their rebellion against Córdoba. The Frankish monarch marched south and took Barcelona, but when he arrived at Zaragoza he found the marcher lords to have had a change of heart, and the city was closed to him. After an unsuccessful siege, Charlemagne withdrew through the Pyrenees, where his rear guard was ambushed at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass. This marked the end of significant Frankish attempts to expand into Iberia, and in 795 Charlemagne would establish the Marca Hispanica in the eastern Pyrenees to serve as a buffer between his realm and the Upper March, while the two realms continued to compete for influence in the western Pyrenees, among the Basques. At the end of the century, two governors of Huesca would again reach out to the Franks, the Muwallad Basque rebel Bahlul Ibn Marzuq in 798, and Azan in 799,[11] while in the latter year at Pamplona, Muhammad ibn Musa, apparently of Muwallad Banu Qasi family of Huesca, was assassinated in what usually is interpreted as a move by a pro-Frankish faction.[12] However, in 816 a Christian army including Franks and Asturian allies and led by Velasco the Gascon was defeated by Emirate armies in 816. This defeat would lead to the ascendancy, originally as clients of Córdoba, of a native Basque dynasty allied by blood to the Muwallad lords of the Upper March as rulers of the nascent state of Pamplona.

Muwallad rivalry, ascendance and decline

8th and 9th centuries

In 781, the emir succeeded in forcing the submission of Husayn in Zaragoza, who had murdered Sulayman in 780, but in 785 the latter's son, Mutrah, rebelled and took Huesca and Zaragoza, before he in turn was murdered by his servants, the kinsmen Amrus ibn Yusuf and Shabrit ibn Rashid, in 791/2. The Emirate brought the loyalty of Amrus by granting him Toledo, but in 798 another Zaragoza rebel, Bahlul Ibn Marzuq, took Huesca from the Banu Salama, and this led to the return of Amrus from Toledo into the Upper March. Amrus expelled Bahlul and fortified Tudela. Another rebellion in Zaragoza, this time led by Furtun ibn Musa of the Banu Qasi, was likewise crushed by Amrus in 802, and he was then given control of Zaragoza and the Upper March.

The Upper March in the 9th century, based on Zaragoza, had other urban settlements at Tudela, Huesca, Tortosa and Calatayud. Al-Hakim I used the local Muwallad families, native Iberian that had converted to Islam, as governors. The decade-long governorship of Amrus bin Yusuf, from whom would descend the Banu Amrus clan, kept the Banu Qasi in check, though they retained their semi-autonomous status despite Amrus's occupation of Tudela, and their alliance and intermarriages with the kingdom of Pamplona also provided them with Basque soldiers.[13]

The capture and execution of Amrus, coupled with the ascendance of their Christian kinsmen in Pamplona, led to the ascendance of the Banu Qasi, and in 842, their leader Musa ibn Musa defied the Umayyads and rebelled against Córdoba with the assistance of his half-brother, Íñigo Arista of Pamplona. Despite the Umayyad capture of Zaragoza in 844 and a son of the Emir Abd-al Rahman II being appointed as governor until 852, Musa retained his autonomy in his ancestral lands.[14] After reconciliation with the Emirate and further episodes of rebellion followed by punitive Umayyad expeditions directed by Abd el-Rahman II, in 852 the new emir, Muhammad, named Musa as Wāli of Zaragoza and governor of the Upper March He was sometimes called 'the Third King of Hispania', alongside the Emir of Córdoba and the King of Asturias, as he controlled Zaragoza, Tudela, Calatayud, Huesca and Toledo, forming a semi-independent state. However, his power in the Upper March came was ended when he and his Basque allies suffered a crushing defeat against the combined armies of Asturias and Pamplona in 859 or 860 at the Battle of Monte Laturce. After fleeing the battle, in which he lost the bulk of his army, Musa was deprived by the emir of all his titles.[15] He died following an expedition against his son-in-law, Azraq ibn Mantel, at Guadalajara in August 862, during which he was wounded and left unable to ride. He died a month later at Tudela.[16]

There followed a decade-long eclipse of the Banu Qasi.[17] After Musa was deprived of governorship of the Upper March, at least three of his four sons were sent to Cordoba as hostages, although one of them, Fortun ibn Musa, quickly pledged obedience to the Emir, and later distinguished himself in the Muslim forces of the Upper March campaigning against the Christians. Musa's the eldest son Lubb ibn Musa, had apparently been appointed by the Emir Muhammad I as governor of Tudela in 859 and by becoming in 860 the ally of king Ordoño I of Asturias, he retained control of Tudela and, by 862 had either secured the release or rescue of his two brothers, who returned to the Upper March. When the Emir Muhammad undertook a campaign in 865–6 against the forces of Álava and the county of Castile, Fortun accompanied the Emir, but Lubb is believed to have remained loyal to Ordoño. However, after Ordoño's death in 966, Lubb was reconciled with the Emir. Lubb was based in the town of Arnedo, having lost control of Huesca.[18] Huesca was governed in 870 by Musa ibn Galind, probably a grandson of Iñigo Arista of Pamplona via his son Galindo who had abandoned Pamplona for Córdoba, and hence akin to the Banu Qasi who had formerly held it.[19][20] He was killed that year by Amrus ibn Umar of the Banu Amrus, who then formed a rebellious alliance against the Emir with Iñigo's eldest son and successor in Pamplona, García Íñiguez. However, in 871, the Emir's general in the Upper March defeated the rebels and captured Zakarayya ibn Amrus, uncle of Amrus ibn Umar, and executed him and his sons at the gates of Zaragoza.[21]

While the forces of the Emirate were dealing with the rebellion of Amrus, in December 871 and January 872 the four sons of Musa ibn Musa, with the support of García Íñiguez, quickly recovered power in Huesca, Tudela and Zaragoza with little resistance, followed by Monzon and Lleida.[22] The initial strategy of Muhammad I was to lead an army into the Upper March in the spring of 873. He decided not to besiege or assault the well-fortified Zaragoza, but was able to capture Huesca. Mutarrif ibn Musa of the Banu Qasi, who had governed Huesca from December 871, and his sons were taken to Cordoba and crucified in September 873, and the Emir installed Amrus ibn Umar in his place at Huesca.[23] Muhammad also installed the Arab Banu Tujib family in Calatayud as a check on the Banu Qasi, then withdrew.[24] Despite the presence of these opponents, the Banu Qasi retained most of the cities of the Upper March and, with Lubb ibn Musa as head of the family, were largely autonomous. Lubb's death in 875 following that in 874 of his brother Fortun, who held Tudela, weakened the family. Ismail ibn Musa, who had formed a marriage alliance with the Banu Jalaf of Barbitanyaas was the only remaining son of Musa but had to contend with his nephew Muhammad ibn Lubb for control of the family and its lands.[25]

An Umayyad army under al-Mundir the heir presumptive of Muhammad I was sent north in 874, to attack Zaragoza first, then to Tudela and the various strongholds of the Banu Qasi and finally to ravage the lands of Pamplona, cutting down trees and uprooting crops. The expedition achieved little, as all the main cities and strongholds of the Upper March that the Banu Qasi held before remained in their hands.[26] A subsequent expedition in 882 involving a failed sieges of Zaragoza and Lleida did result, as had the 874 expedition, in the widespread destruction of crops and created disharmony within the Banu Qasi clan, leaving Muhammad ibn Lubb isolated. However and attempt by Ismail ibn Musa and the sons of Fortun ibn Musa to defeat Muhammad in battle led to their defeat, capture and forced their surrender of Tudela and several castles[27] A further Umayyad expedition in 882 particularly directed against Zaragoza was unsuccessful, but a further attack starting in 884 finally broke Muhammad ibn Lubb's resistance[27]

The cumulative pressure of these repeated attacks forced Muhammad ibn Lubb ibn Qasi to sell Zaragoza in 885. And when in 886 the city was seized from the Emir's own governor by the Banu Tujib the Emir acquiesced, elevating this family as major regional rivals to the Muwallad families. The Banu Qasi again rebelled, and the Emir captured and crucified several members of the family, and in 887 we find Masud ibn Amrus of the Banu Amrus controlling Huesca when he was murdered and supplanted by his distant kinsman Muhammad al-Tawil of the Banu Shabrit.[28] In 890 al-Tawil defeated another Banu Qasi rebellion led by Isma'il ibn Musa, uncle of Muhammad ibn Lubb. Though al-Tawil claimed the lands of the defeated Isma'il, the Emir would not risk such an increase in his power, and instead granted them to Muhammad ibn Lubb, who had remained loyal during his uncle's rebellion.

Muhammad ibn Lubb tried to reverse these family losses by carrying out a lengthy but unsuccessful siege of Zaragoza, held by the a Banu Tujib governor, and even when Muhammad was killed outside the city's walls in 898,[29] the siege continued under his son Lubb ibn Muhammad, who became wali of Tudela and Lleida and lord of the family lands in the Upper Ebro.[30][31] When the siege was finally broken, the Banu Tujib they seized Ejea from the Banu Qasi.[32] Nonetheless, Lubb experienced a period of success, twice defeating al-Tawil's armies, capturing the latter and requiring an exorbitant ransom, and in 897 he defeated and killed his Christian neighbor, Wilfred the Hairy of Barcelona.[33]

10th century

In the early 10th century, the dynamics of the Upper March were fundamentally altered by changes in the leadership of the states to the north and south. In 905, the Córdoba client Fortún Garcés of Pamplona was supplanted by the anti-Muslim Sancho I, while in 911, Abd al-Rahman III became Emir of Córdoba and began a policy of tightening central control over his fractious regional lords. When in 907 Lubb attacked Pamplona, he was ambushed and killed by its new king.[34] With Lubb's death, the Banu Qasi ceased to hold the governorship of Lleida, and the Banu al-Tawil seized Barbastro, Alquézar and Monzón.[32] One of Lubb's sons, Abd Allah, was murdered by his uncle Abd Allah ibn Muhammad, who became wali of Huesca and in 911 allied himself with family rival Muhammad al-Tawil. They passed through the lands of al-Tawil's Christian brother-in-law Galindo Aznárez II of Aragon to again attack Sancho's Pamplona realm, only to be crushed by the new Christian monarch,[35] who in turn attacked Tudela in 915, capturing and later murdering Abd Allah.[36] His succession was contested between his brother Mutarrif and son Muhammad, with the latter killing his uncle the next year to take the leadership of the family, while his cousin Muhammad ibn Lubb, a son of Lubb ibn Muhammad, established himself in the eastern Upper March, rataking Monzón from the sons of Muhammad al-Tawil after the latter died in 913 during an attack on Barcelona.[37] and also regained Lleida when in 922 its residents turned against their lord, Amrus ibn al-Tawil.[38]

In 918, Sancho I of Pamplona captured Calahorra, previously held by the Banu Qasi for almost a century, and he besieged, and the next year captured and burnt Monzón, which the Banu Qasi never regained.[39] Abd al-Rahman III in 924 led an army north and removed Muhammad ibn Abd Allah from control of Huesca, sending him to Cordoba.[40] With pressure on the families of the Upper March from the monarchs of Cordoba to the south, Pamplona to the north and León to their west, and weakened by internal family struggles, the sole remaining Banu Qasi lord, Muhammad ibn Lubb, retained only Barbastro and some small towns nearby. One-by-one these expelled him in favour of the Banu al-Tawil, and by 928 Muhammad only held the small town of Ayera. He was assassinated in 929, bringing an end to the Banu Qasi presence on the Upper March.[31][41]

With the decline removal of the Banu Qasi, the sons of Muhammad al-Tawil jockeyed for control over several of the coras of the Upper March,[42] but amidst internecine struggles, rebellions and their own failure to maintain popular support, they were progressively marginalized. Abd al-Malik ibn Muhammad al-Tawil had succeeded his father at Huesca and installed his brother Amrus at Monzón, though the latter soon lost it to the Banu Qasi.[43] Abd al-Malik's hold on Huesca was challenged by a series of rebellions by Banu Shabrit cousins, whom he killed, only to himself be killed and supplanted by his brother Amrus in 918.[44] However, the Huesca citizenry rejected Amrus in favor of his brother Fortun ibn Muhammad al-Tawil. Amrus fled to Barbastro and Alquézar, and was later offered Lleida by its residents,[45] only for them to turn the city over to Muhammad ibn Lubb ibn Qasi in 922.[46] He was captured by the Banu Tujib in 932, submitted to Abd al-Rahman III, and was killed participating in the Caliph's 934/5 campaign against Zaragoza and its rebel Banu Tujib lords.[47] Fortun ibn Muhammad al-Tawil had submitted to Abd al-Rahman at the same time as Amrus, but in 933 he was expelled from Huesca after forming a pact with rebel Muhammad ibn Hasim al-Tujibi and replaced by his brother Yahya ibn Muhammad al-Tawil, and though Fortun went to Córdoba and abased himself before the Caliph, begging to be restored, Abd al-Rahman instead sent an outsider, Ahmed ibn Muhammad ibn Ilyas of Valencia, and the sons of Fortun and Yahya left the Upper March for Córdoba. However, after Ahmed struggled to retain control against the rebel Banu Tujib, Abd al-Rahman restored Fortun to Huesca in 936/7 against the will of the city's residents.[48] When Fortun accompanied the Caliph on a campaign against León, he turned control of Huesca over to his brother Musa, who in 940 was formally named as wali of Huesca and Barbastro, though the latter was given to his brother Yahya in 942, to be followed by another brother, Lubb ibn Muhammad in 951, and Lubb's son Yahya in 955.[49] In 957/8, the Caliph experimented with power sharing, making Yahya ibn Lubb and Abd al-Malik ibn Musa, who had succeeded his father in Huesca in 954, joint rulers of both Huesca and Barbastro, but he again segregated their control of the two coras in 959.[50] By this time the Banu al-Tawil had long since lost their ability to mount a credible challenge for the control of the Upper March against the new dominant family, the Banu Tujib, and the last of the Banu al-Tawil is seen fighting in a tournament in Córdoba in 974.[51]

Ascendance of the Banu Tujib

The influence of the Umayyad Emirs in all the marches had waned after the death of Abd al-Rahman II, but in 890 the Emir Abd Allah appointed his friend, Abd al-Rahman al-Tujibi, of the Arab Banu Tujib family that had governed Catalayud and Daroca since 872, to be governor of Zaragoza and to have control of the Upper March[52] They in turn rebelled against Abd ar-Rahman III, and were briefly forced or coerced into alliance with Ramiro II of León. Córdoba brought them back into submission, and the Banu Tujib head, Abu Yahya, was captured in the defeat of Caliph's army at the Battle of Simancas in 939. He was released in 941 and restored in Zaragoza by 942, to serve as Cordoba's proxy in campaigns against Ramiro's allies in Pamplona. The Banu Tujib allied themselves in 983 with Almanzor, de facto ruler of Córdoba, but were again deprived and their head killed in 989 when they conspired with his son. However, their power in the region made them irreplaceable and they were again restored. They reached the pinnacle of their power and brought the Upper March to an end in 1018, when after the formal overthrow of the Caliphs of Córdoba, Al-Mundhir ibn Yahya al-Tujibi declared independence, converting what remained of the Upper March into the Taifa of Zaragoza. They would control the taifa for just 21 years before a coup within the family led to their expulsion by the Banu Hud of Lleida, and that family in turn ruled the Zaragoza taifa until it was conquered by the Almoravids in 1110. The region was permanently wrested from Muslim control by Alfonso I of Aragon in 1118.

The Banu Tujib, who had been granted Calatayud in 872 and Zaragoza in 886, now become the uncontested lords of the Upper March. They in turn rebelled against Abd ar-Rahman III, and were briefly forced or coerced into alliance with Ramiro II of León. Córdoba brought them back into submission, and the Banu Tujib head, Abu Yahya, was captured in the defeat of Caliph's army at the Battle of Simancas in 939. He was released in 941 and restored in Zaragoza by 942, to serve as Cordoba's proxy in campaigns against Ramiro's allies in Pamplona.

References

- Reilly, pp. 52–54

- Kennedy, p. 39

- Reilly, p.56

- Reilly, p.75

- Reilly, p. 77

- Manzano Moreno, pp. 185-187

- Cabañero Subiza, p. 75

- Cabañero Subiza, pp. 82

- Cabañero Subiza, pp. 79-81

- Cabañero Subiza, pp. 76

- Sénac (2020), p. 29

- Cañada Juste, p.

- Kennedy, p.56

- Kennedy, p.57

- Kennedy, pp.57-8

- Cañada Juste, p.39

- Flood, p.31

- Cañada Juste, p.41

- Sánchez Albornoz, p. 266, n. 8

- Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa, "Galindo Iñiguez"

- Cañada Juste, pp.42-3

- Cañada Juste, p.43

- Cañada Juste, pp.45-7

- Cañada Juste, pp.44, 48

- Cañada Juste, pp.48-50

- Cañada Juste, pp.51-4

- Cañada Juste, pp.56-8

- Sénac (2010), p. 30

- Cañada Juste, p. 74

- Cañada Juste, pp. 70, 74-5

- Catlos, p. 78

- Cañada Juste, p. 77

- Reilly, p.83

- Cañada Juste, pp. 74-5

- Cañada Juste, p. 79

- Cañada Juste, pp. 81–83

- Cañada Juste, pp. 83–84

- Cañada Juste, p. 89

- Cañada Juste, pp. 85–86

- Cañada Juste, pp. 88–89

- Cañada Juste, pp. 89–90

- Cañada Juste, p. 83

- de la Granja, pp. 521-522

- de la Granja, p. 522

- de la Granja, pp. 522-523

- Cañada Juste, pp. 89

- de la Granja, pp. 523-525

- de la Granja, pp. 525-528

- de la Granja, pp. 529-531

- de la Granja, pp. 529, 531

- Sénac (2000), p. 529, 531

- Kennedy, pp. 80–1

Cited sources

- J. Bosch Vilá, (1960). "El reino de taifas de Zaragoza: Algunos aspectos de la cultura árabe en el valle del Ebro." Cuadernos de Historia Jerónimo Zurita, vols 10–11.

- Bernabé Cabañero Subiza, (2006). "Una comarca prefigurada en época islámica en el 'amal de Barbităniyya" in Juste, N. (coord.), Comarca de Somontano de Barbastro (Gobierno de Aragón, Colección Territorio, 21) Zaragoza, pp. 75–86.

- Alberto Cañada Juste, (1980). "Los Banu Qasi (714 - 924)." Príncipe de Viana, Nos. 158–159, pp. 5–96. ISSN 0032-8472.

- B. A. Catlos, (2018). Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-78738-003-5.

- "Galindo Iñiguez", Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa (online, in Spanish).

- Fernando de la Granja, (1967). "La Marca Superior en la Obra de al-'Udrí", Estudios de la Edad Media de la Corona de Aragón, vol. 8, pp. 457–545.

- T.M. Flood, (2018). Rulers and Realms in Medieval Iberia, 711-1492. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-47667-471-1.

- H. Kennedy, (2014). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-58249-515-9.

- Manzano Moreno, Eduardo (1986). "La rebelión del año 754 en la Marca Superior y su tratamiento en las crónicas árabes". Studia historica. Historia medieval (4): 185–203..

- Bernard F. Reilly, (1993). The Medieval Spains. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39741-3.

- Claudio Sánchez Albornoz, (1958). "La Epistola de S. Eulogio y el Muqtabis de Ibn Hayyan", Príncipe de Viana, vol. 19, pp. 265–266. ISSN 0032-8472.

- Philippe Sénac, (2000). La frontière et le hommes, VIIIe-XIIe siècle: le peuplement musulman au nord de l'Èbre et les débuts de la reconquête aragonaise, Maisonneuve & Larose.

- Philippe Sénac, (2010). "Les seigneurs de la Marche (Aṣḥābu al-Ṯaġri): les Banū 'Amrūs et les Banū Šabrīṭ de Huesca", Cuadernos de Madinat al-Zahra: Revista de difusión científica del Conjunto Arqueológico Madinat al-Zahra, No. 7, pp. 27–42. ISSN 1139-9996.

General sources

- Corral Lafuente, José Luis, "El sistema urbano en la Marca Superior de al-Andalus", Turiaso, n.º 7, 1987 (Issue dedicated to Islam in Aragón), pp. 23–64. ISSN 0211-7207

- "Marca superior de Al-Andalus", Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa (online, in Spanish).

- Fletcher, Richard (1999). La España mora (in Spanish). Nerea. pp. 213. ISBN 9788489569409.

- Molina Martínez, Luis and María-Luisa Ávila Navarro, "La división territorial en la marca Superior de al-Andalus", Historia de Aragón, 3 (1985), pp. 11–30. ISBN 84-7611-024-3.

- Sénac, Philippe, La marche supérieure d'al-Andalus et l'Occident chrétien, Madrid, Casa de Velázquez-Universidad de Zaragoza, 1991. ISBN 978-84-86839-22-2.

- Souto Lasala, Juan Antonio, "El poblamiento del término de Zaragoza:(siglos VIII-X): los datos de las fuentes geográficas e históricas", Anaquel de estudios árabes, no. 3, (1992), pp. 113–152. ISSN 1130-3964.

- Souto Lasala, Juan Antonio, "El noroeste de la frontera superior de Al-Andalus en época omeya: poblamiento y organización territorial", García Sánchez III "el de Nájera" un rey y un reino en la Europa del siglo XI, XV Semana de Estudios Medievales, Nájera, Tricio y San Millán de la Cogolla del 2 al 6 de agosto de 2004 / coord. por José Ignacio de la Iglesia Duarte, 2005, pp. 253–268. ISBN 84-95747-34-0.

- Turk, Afif, "La Marca Superior como vanguardia de al-Andalus: Su papel político y su espíritu de independencia", Al-Andalus Magreb: Estudios árabes e islámicos n.º 6 (1998), pp. 237–250. ISSN 1133-8571.