Variant of Concern 202012/01

Variant of Concern 202012/01, abbreviated VOC-202012/01 (also known as lineage B.1.1.7, 20I/501Y.V1 or commonly as the UK variant or British variant; see § Names), is a variant of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. One of several variants believed to be of particular importance, it is estimated to be 30%–80%[2] more transmissible than wild-type SARS-CoV-2 and was detected in November 2020 from a sample taken in September, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom; it began to spread quickly by mid-December, and is correlated with a significant increase in SARS-CoV-2 infections in the country. This increase is thought to be at least partly because of one or more mutations in the virus's spike protein. The variant is also notable for having more mutations than normally seen.[3]

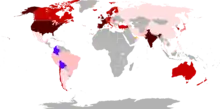

Legend:

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

As of January 2021, more than half of all genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 was carried out in the UK.[4] This has given rise to questions as to the variant's origins, and how many other important variants may be circulating around the world.[5][6]

As of late January 2021, most locations outside the original focus have not reported sustained transmission, and many cases have known travel links to the focal location. Increasing numbers of international cases is currently likely due to increased surveillance and vigilance.[1]

On 2 February 2021, Public Health England reported that they had detected "[a] limited number of B.1.1.7 VOC 202012/01 genomes with E484K mutations",[7] which is also present in the South Africa and Brazil variants;[8] this mutation may reduce vaccine effectiveness.[8] In Denmark, Statens Serum Institut also found 31 cases of a E484K mutated B117 variant, during the five weeks from 29 December 2020 to 30 January 2021 (week 53 to week 4), corresponding to 2.45% of all detected B117 variants in the samee period.[9]

Names

The variant is known by several names. In British government and media reports it may be referred to as UK COVID-19 variant, UK coronavirus variant, the new variant or, particularly outside the UK, as the UK variant or British variant.[10] It is sometimes called the Kent variant, with no further explanation.[8]

In scientific use the variant had originally been named the first Variant Under Investigation in December 2020 (VUI – 202012/01) by Public Health England,[11][lower-alpha 1] but was reclassified to a Variant of Concern (Variant of Concern 202012/01, abbreviated VOC-202012/01) by Meera Chand and her colleagues in a report published by Public Health England on 21 December 2020.[lower-alpha 2] In a report written on behalf of COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium, Andrew Rambaut and his co-authors, using the Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak Lineages (PANGOLIN) tool, referred to the variant as lineage B.1.1.7,[13] while Nextstrain dubbed the variant 20I/501Y.V1.[14]

Detection

VOC-202012/01 was first detected in early December 2020 by combining genome data with knowledge that the rates of infection in Kent were not falling despite national restrictions.[3][15]

The two earliest genomes that belong to the B.1.1.7 lineage were collected on 20 September 2020 in Kent and another on 21 September 2020 in Greater London.[13] These sequences were submitted to the GISAID sequence database (sequence accessions EPI_ISL_601443 and EPI_ISL_581117 respectively). As of 15 December, there were 1623 genomes in the B.1.1.7 lineage. Of these 519 were sampled in Greater London, 555 in Kent, 545 elsewhere in England, Scotland and Wales, and 4 in other countries.[13]

Backwards tracing using genetic evidence suggests this new variant emerged in September 2020 and then circulated at very low levels in the population until mid-November. The increase in cases linked to the new variant first became apparent in late November when Public Health England (PHE) was investigating why infection rates in Kent were not falling despite national restrictions. PHE then discovered a cluster linked to this variant spreading rapidly into London and Essex.[16]

Although the variant was first detected in Kent, it may never be known where it originated. Discovery in the UK may merely reflect that the UK does more sequencing than many other countries. It has been suggested that the variant may have originated in a chronically infected immunocompromised person, giving the virus a long time to replicate and evolve.[3][17]

Characteristics

Genetics

| Gene | Nucleotide | Amino acid |

|---|---|---|

| ORF1ab | C3267T | T1001I |

| C5388A | A1708D | |

| T6954C | I2230T | |

| 11288–11296 deletion | SGF 3675–3677 deletion | |

| Spike | 21765–21770 deletion | HV 69–70 deletion |

| 21991–21993 deletion | Y144 deletion | |

| A23063T | N501Y | |

| C23271A | A570D | |

| C23604A | P681H | |

| C23709T | T716I | |

| T24506G | S982A | |

| G24914C | D1118H | |

| ORF8 | C27972T | Q27stop |

| G28048T | R52I | |

| A28111G | Y73C | |

| N | 28280 GAT→CTA | D3L |

| C28977T | S235F | |

| Source: Chand et al., table 1 (p. 5) | ||

Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 are common: over 4,000 mutations have been detected in the spike glycoprotein alone, according to the COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium.[18]

VOC-202012/01 is defined by 23 mutations: 14 non-synonymous mutations, 3 deletions, and 6 synonymous mutations[19] (i.e., there are 17 mutations that change proteins and six that do not[3]).

Transmissibility

Estimates of VOC-202012/01's transmissibility have varied greatly across different studies: in a preprint, the Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine reported that the variant was 56% (50%–74%) more transmissible than other variants across three regions in England (East of England, South East of England, and London) in early December 2020,[20] while a peer-reviewed article concluded that it was 75% (70%–80%) more transmissible in the UK between October and November 2020.[21] The Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport calculated that the variant was 49% more transmissible in the Netherlands from 1 to 14 January 2021;[22] the Danish Statens Serum Institut found it to be 55% (40%–70%) more transmissible in Denmark around mid-January 2021.[23]

On 18 December 2020—early on in the risk assessment of the variant—the UK scientific advisory body New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG) concluded that they had moderate confidence that VOC-202012/01 was substantially more transmissible than other variants, but that there were insufficient data to reach any conclusion on underlying mechanism of increased transmissibility (e.g. increased viral load, tissue distribution of virus replication, serial interval etc.), the age distribution of cases, or disease severity.[24] Data seen by NERVTAG indicated that the relative reproduction number ("multiplicative advantage") was determined to be 1.74, that is, that the variant is 74% more transmissible, assuming a 6.5-day generational interval. It was demonstrated that the variant grew fast exponentially with respect to the other variants.[25][26][27] The variant out-competed the ancestral variant by a factor of every two weeks. Another group came to similar conclusions, generating a replicative advantage, independent of "protective measures", of 2.24 per generation of 6.73 days, out-competing the ancestral variant by every two weeks.[28] Similarly, in Ireland, the variant—as indicated by the historically rare missing S-gene[lower-alpha 3] detection (S-gene target failure [SGTF])—went from 16.3% to 46.3% of cases in two weeks. This demonstrates, based on the statistics of 116 positive samples, that a relative growth during that time of occurred, when accounting for the declining percentage of the other variants.[30] The variant became the dominant variant in London, East of England and the South East from low levels in one to two months. A surge of SARS-CoV-2 infections around the start of the new year is seen as being the result of the elevated transmissibility of the variant, while the other variants were in decline.[31][32][33]

One of the most important changes in VOC-202012/01 seems to be N501Y,[18] a change from asparagine (N) to tyrosine (Y) in amino-acid position 501.[34] This is because of its position inside the spike protein's receptor-binding domain (RBD)—more specifically inside the receptor-binding motif (RBM),[35] a part of the RBD[36]—which binds human ACE2.[37] Mutations in the RBD can change antibody recognition and ACE2 binding specificity[37] and lead to the virus becoming more infectious;[18] indeed, Chand et al. concluded that "[i]t is highly likely that N501Y affects the receptor-binding affinity of the spike protein, and it is possible that this mutation alone or in combination with the deletion at 69/70 in the N-terminal domain (NTD) is enhancing the transmissibility of the virus".[38]

The CDC has presented epidemiological models, assuming 50% more transmissibility than current U.S. variants, that infer B.1.1.7 would become the predominant variant in March 2021.[39]

It is not clear why the pace of replacement of non-VOC-202012/01 variants is different in parts of the world.[40] Regarding this, Brendan B. Larsen and Michael Worobey of the University of Arizona hypothesised in a preprint:

One model is that B.1.1.7’s transmission advantage may vary with mitigation intensity. Perhaps this lineage of SARS-CoV-2 [lineage B.1.1.7], with demonstrably higher viral loads in the upper airway than other variants, is able to seed superspreader events with relative ease when mitigation efforts are comparatively lax, but its transmission advantage is less acute when the playing field is leveled by, for example, widespread mask use and indoor crowd avoidance. Another possibility is that the non-B.1.1.7 lineages circulating in the US, particularly in California, may be more transmissible than the non-B.1.1.7 lineages in England with which B.1.1.7 has been competing, giving B.1.1.7 less of a transmission advantage and, thus, a slower displacement rate of non-B.1.1.7 lineages. An example of this might be a new variant with the Spike RBD mutation L452R that was recently described in the press in California.[40]

Virulence

NERVTAG concluded on 18 December 2020 that there were insufficient data to reach a conclusion regarding disease severity. At prime minister Boris Johnson's briefing the following day, officials said that there was "no evidence" as of that date that the new variant caused higher mortality, or was affected differently by vaccines and treatments;[41] Vivek Murthy agreed with this.[42] Susan Hopkins, the joint medical adviser for the NHS Test and Trace and Public Health England (PHE), declared in mid-December 2020: "There is currently no evidence that this strain causes more severe illness, although it is being detected in a wide geography, especially where there are increased cases being detected."[18] Around a month later, however—on 22 January 2021—Johnson said that "there is some evidence that the new variant [VOC-202012/01] [...] may be associated with a higher degree of mortality", though Sir Patrick Vallance, the government's Chief Scientific Advisor, stressed that there is not yet enough evidence to be fully certain of this.[43] Neil Ferguson of NERVTAG told ITV News: "Four groups—Imperial, LSHTM, PHE and Exeter—have looked at the relationship between people testing positive for the variant vs old strains and the risk of death; that suggests a 1.3-fold increased risk of death."[44] In a paper analysing different studies on VOC-202012/01 death rate, NERVTAG concluded that "[t]here is a realistic possibility that VOC B.1.1.7 is associated with an increased risk of death compared to non-VOC viruses".[45]

Genetic sequencing of VOC-202012/01 has shown a Q27stop mutation which "truncates the ORF8 protein or renders it inactive".[13] An earlier study of SARS-CoV-2 variants which deleted the ORF8 gene noted that they "have been associated to milder symptoms and better disease outcome".[46] The study also noted that "SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 is an immunoglobulin (Ig)–like protein that modulates pathogenesis", "SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 mediates major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I) degradation", and "SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 suppresses type I interferon (IFN)–mediated antiviral response".[46]

Referring to amino-acid position 501 inside the spike protein (VOC-202012/01 has a mutation, N501Y, in this position), Chand et al. concluded that "it is possible that variants at this position affect the efficacy of neutralisation of virus",[38] but noted that "[t]here is currently no neutralisation data on N501Y available from polyclonal sera from natural infection".[38] 69–70del—a deletion of the amino acids in positions 69–70 of the spike protein—has, however, been discovered "in viruses that eluded the immune response in some immunocompromised patients",[47] and has also been found "in association with other RBD changes".[38]

Rapid-antigen-test effectiveness

Several rapid antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2 are in widespread use globally for COVID-19 diagnostics. They are believed to be useful in stopping the chain of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by providing the means to rapidly identify large number of cases as part of a mass testing program. Following the emergence of VOC-202012/01, there was initially concern that rapid tests might not detect it, but Public Health England determined that rapid tests evaluated and used in the United Kingdom detect the variant.[48]

Vaccine effectiveness

As of late 2020, several COVID-19 vaccines were being deployed or under development.

However, as further mutations occur, concerns were raised as to whether vaccine development would need to be altered. SARS-CoV-2 does not mutate as quickly as, for example, influenza viruses, and the new vaccines that had proved effective by the end of 2020 are types that can be adjusted if necessary.[49] As of the end of 2020, German, British, and American health authorities and experts believe that existing vaccines will be as effective against the new VOC-202012/01 variant as against previous variants.[50][51]

On 18 December, NERVTAG determined "that there are currently insufficient data to draw any conclusion on [...] [a]ntigenic escape".[24]

As of 20 December 2020, Public Health England confirmed there is "no evidence" to suggest that the new variant would be resistant to the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine currently being used in the UK's vaccination programme, and that people should still be protected.[16]

Spread

Cases of VOC-202012/01 are likely to be undetected in most countries as most tests do not distinguish between this variant and other SARS-CoV-2 variants, and as many SARS-CoV-2 infections are not detected at all. RNA sequencing is required for detection of this variant,[58] although variant-specific PCR testing is becoming available.[59]

The first case was likely in mid-September 2020 in London or Kent, United Kingdom.[60] As of 13 December 2020, 1,108 cases with this variant had been identified in the UK in nearly 60 different local authorities. These cases were predominantly in the south east of England. The variant has also been identified in Wales and Scotland.[61] By November, around a quarter of cases in the COVID-19 pandemic in London were being caused by the new variant, and by December, that was a third.[62] In mid-December, it was estimated that almost 60 percent of cases in London involved VOC-202012/01.[63] By 25 January 2021, the number of confirmed and probable UK cases had grown to 28,122.[64]

The variant became dominant in the United Kingdom and Ireland,[65] respectively in week 52 of 2020[66] and in week 2 of 2021.[67] In the Netherlands, it probably became dominant around January 26.[22] In Portugal the variant represented 20% of the infections for data reported mid-January, and probably became dominant by the end of January.[68] In Israel the variant was estimated to account for 30% to 40% of infections on January 19.[69] In Belgium 25% of cases were of the variant as of January 24.[70] In Denmark the variant grew from 0.3% (week 46) to 19.5% (week 4),[9] and is expected to become dominant (over 50%) around mid-February and comprise around 80% of the total circulating variants by early March.[23] In Sweden the variant share was found to be 11% for week 4 across four of its southern regions (Skåne, Västmanland, Västra Götaland, and Gävleborg).[71] In France the variant grew from a share of 3.3% on January 7-8[72] to 14.0% on January 27,[73] with the expectation of becoming dominant around week 8-11 of 2021.[74] In Spain, an estimated 5 to 10% of cases are of the variant as of January 29.[75] In the US, where the variant was at around 0.3% at the start of the 2021, it is expected to become predominant in March of the same year.[76][77]

The relatively low sensitivity of the projected dominance dates to the current percentage of the variant is due to its fast relative exponential growth. It is presumed the variant will become dominant over the ancestral variant globally, although it may be taken over by other variants.[78][79]

| Development of the B.1.1.7 lineage (share of analyzed SARS-CoV-2–positive tests) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Week 43 | Week 44 | Week 45 | Week 46 | Week 47 | Week 48 | Week 49 | Week 50 | Week 51 | Week 52 | Week 53 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 |

| United Kingdom[66] | 0.3% | 1.7% | 2.9% | 6.3% | 10.9% | 10.1% | 13.8% | 33.7% | 48.3% | 53.8% | 69.1% | – | – | – | – |

| Ireland[30][67] | – | – | 1.9% (few data) |

0.0% (few data) |

0.0% (few data) |

6.0% (few data) |

1.6% (few data) |

1.4% | 8.6% | 16.3% | 26.2% | 46.3% | 57.7% | 62.8% | – |

| Netherlands[80] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.1% | 0.7% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 5.2% | 8.8%[81] | 19.8%[22] | 30.4%[22] | – |

| Denmark[9] | – | – | – | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 2.0% | 2.3% | 4.0% | 7.5% | 12.8% | 19.5% |

| France[72][73] | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.3% | – | – | 14.0% |

| Sweden[71] | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 11.4%[lower-alpha 4] |

Countries reporting a first case appearance

Cases of the variant began to be reported globally during December, being reported in Denmark,[41][82] Belgium,[83] the Netherlands, Australia[41][82] and Italy.[84] Shortly after, several other countries confirmed their first cases, the first of whom were found in Iceland and Gibraltar,[85][86] then Singapore, Israel and Northern Ireland on 23 December,[87][88][89] Germany and Switzerland on 24 December,[90][91] and the Republic of Ireland and Japan confirmed on 25 December.[92][93]

The first cases in Canada, France, Lebanon, Spain and Sweden were reported on 26 December.[94][95][96][97] Jordan, Norway, and Portugal reported their first case on 27 December,[98][99] Finland and South Korea reported their first cases on 28 December,[100][101] and Chile, India, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates reported their first cases on 29 December.[102][103][104][105] The first case of new variant in Malta and Taiwan are reported on 30 December.[106][107] China and Brazil reported their first cases of the new variant on 31 December.[108][109] The United Kingdom and Denmark are sequencing their SARS-CoV-2 cases at considerably higher rates than most others,[110] and it was considered likely that additional countries would detect the variant later.[111]

The United States reported a case in Colorado with no travel history on 29 December, the sample was taken on 24 December.[112] On 6 January 2021, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that it had found at least 52 confirmed cases in California, Florida, Colorado, Georgia, and New York.[113] In the following days, more cases of the variant were reported in other states, leading former CDC director Tom Frieden to express his concerns that the U.S. will soon face "close to a worst-case scenario".[114]

Turkey detected its first cases in 15 people from England on 1 January 2021.[115] It was reported on 1 January that Denmark had found a total of 86 cases of the variant, equalling an overall frequency of less than 1% of the sequenced cases in the period from its first detection in the country in mid-November to the end of December;[116][117] this had increased to 1.6% of sequenced tests in the period from mid-November to week two of 2021, with 7% of sequenced tests in this week alone being of the B.1.1.7 lineage.[118] Luxembourg and Vietnam reported their first case of this variant on 2 January 2021.[119][120]

On 3 January 2021, Greece and Jamaica detected their first four cases of this variant[121][122] and Cyprus announced that it had detected VOC-202012/01 in 12 samples.[123] At the same time, New Zealand and Thailand reported their first cases of this variant, where the former reported six cases made up of five from the United Kingdom and one from South Africa,[124] and the latter reported the cases from a family of four who had arrived from Kent.[125] Georgia reported its first case[126] and Austria reported their first four cases of this variant, along with one case of 501.V2 variant, on 4 January.[127]

On 5 January, Iran,[128] Oman,[129] and Slovakia reported their first cases of VOC-202012/01.[130] On 8 January, Romania reported its first case of the variant, an adult woman from Giurgiu County who declared not having left the country recently.[131] On 9 January, Peru confirmed its first case of the variant.[132] Mexico and Russia reported their first case of this variant on 10 January,[133] then Malaysia and Latvia on 11 January.[134][135]

On 12 January, Ecuador confirmed its first case of this variant.[136] The Philippines and Hungary both detected the presence of the variant on 13 January.[137][138] The Gambia recorded first cases of the variant on 14 January with it being the first confirmation of the variant's presence in Africa.[139] On 15 January, the Dominican Republic confirmed its first case of the new variant[140] and Argentina confirmed its first case of the variant on 16 January.[141] Czech Republic and Morocco reported their first cases on 18 January[142][143] and Kuwait confirmed its first cases of the variant on 19 January.[144] Nigeria confirmed its first case on 25 January.[145] On 28 January, Senegal detected its first case of the variant.[146] On 4 February, health authorities in Uruguay announced the first case of the variant in the country. The case was detected in a person who entered the country on 20 December 2020 and has been in quarantine ever since.[147]

In early January, an outbreak linked to a primary school led to the detection of at least 30 cases of the new variant in the Bergschenhoek area of the Netherlands, signifying local transmission.[148]

On 16 January, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health confirmed the variant was detected in L.A. County, with public health officials believing that it is spreading in the community.[149]

N501Y change

A variant with the same N501Y change (which may result in higher transmissibility), but with a separate lineage from the UK variant, was detected in South Africa, and named 501.V2.[47] The N501Y change has also been detected elsewhere: in Australia in June–July, in the US in July, and in Brazil (B.1.1.28 in April and B.1.1.248 since), and it is not yet clear if it arose spontaneously in the UK, or was imported.[150]

Control

In the presence of an extra infectious variant, stronger physical distancing and lockdown measures were opted for to avoid overwhelming the population due to its tendency to grow exponentially.[151]

All countries of the United Kingdom were affected by domestic travel restrictions in reaction to the increased spread of COVID-19—at least partly attributed to VOC-202012/01—effective from 20 December 2020.[152][153] During December 2020, an increasing number of countries around the world either announced temporary bans on, or were considering banning, passenger travel from the UK, and in several cases from other countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark. Some countries banned flights; others allowed only their nationals to enter, subject to a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.[154] A WHO spokesperson said "Across Europe, where transmission is intense and widespread, countries need to redouble their control and prevention approaches". Most bans by EU countries were for 48 hours, pending an integrated political crisis response meeting of EU representatives on 21 December to evaluate the threat from the new variant and coordinate a joint response.[155][156]

Many countries around the world imposed restrictions on passenger travel from the United Kingdom; neighbouring France also restricted manned goods vehicles (imposing a total ban before devising a testing protocol and permitting their passage once more).[157] Some also applied restrictions on travel from other countries.[158][159][160][161] As of 21 December 2020, at least 42 countries had restricted flights from the UK,[154] and Japan was restricting entry of all foreign nationals after cases of the new variant were detected in the country.[162]

The usefulness of travel bans has been contested as limited in cases where the variant has likely already arrived, especially if the estimated growth rate per week of the virus is higher locally.[163][164]

Notes

- Written as VUI 202012/01 (Variant Under Investigation, year 2020, month 12, variant 01) by GISAID[lower-alpha 5] and the ECDC.[lower-alpha 6]

- This redesignation is explained in the report:

SARS-COV-2 variants if considered to have concerning epidemiological, immunological or pathogenic properties are raised for formal investigation. At this point they are designated Variant Under Investigation (VUI) with a year, month, and number. Following risk assessment with the relevant expert committee, they are designated Variant of Concern (VOC). This variant was designated VUI-202012/01 on detection and on review re-designated as VOC-202012/01 on 18/12/20 and GISAID entry EPI_ISL_601443 was declared to be the canonical genome.[12]

- SARS-CoV-2's S gene encodes its spike protein.[29]

- In Sweden, a study comprising 11% of all positive samples nationwide for week 4, found the B117 variant share to be 11.4% (250/2200). Samples were however only collected from four southern regions (Skåne, Västmanland, Västra Götaland, and Gävleborg). The national authorities plan to expand the study to cover more/all regions for the following weeks in February 2021.[71]

- "UK reports new variant, termed VUI 202012/01". GISAID. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Threat Assessment Brief: Rapid increase of a SARS-CoV-2 variant with multiple spike protein mutations observed in the United Kingdom (PDF) (Report). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). 20 December 2020.

References

- "B.1.1.7 report". cov-lineages.org. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Kennedy, David (15 January 2021). "What you need to know about the new COVID-19 variants". The Conversation. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Peacock, Sharon (22 December 2020). "Here's what we know about the new variant of coronavirus". The Guardian.

- Donnelly, Laura (26 January 2021). "UK to help sequence mutations of Covid around world to find dangerous new variants". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Rachel Schraer (22 December 2020). "Covid: New variant found ‘due to hard work of UK scientists". BBC. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Sugden, Joanna (30 January 2021). "How the U.K. Became World Leader in Sequencing the Coronavirus Genome". The Wall Street Journal.

- Investigation of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant Variant of Concern 202012/01: Technical briefing 5 (PDF) (Report). Public Health England. 2 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Roberts, Michelle (2 February 2021). "UK variant has mutated again, scientists say". BBC News. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Statens Serum Institut (5 February 2021). "Status for udvikling af SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern (VOC) i Danmark" [Status of development of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern (VOC) in Denmark] (in Danish). Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- For an extensive list of news sources using these terms, see UK Covid-19 variant, UK coronavirus variant and UK variant.

- "PHE investigating a novel strain of COVID-19". Public Health England. 14 December 2020.

- Chand, Meera; Hopkins, Susan; Dabrera, Gavin; Achison, Christina; Barclay, Wendy; Ferguson, Neil; Volz, Erik; Loman, Nick; Rambaut, Andrew; Barrett, Jeff (21 December 2020). Investigation of novel SARS-COV-2 variant: Variant of Concern 202012/01 (PDF) (Report). Public Health England. p. 2. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Rambaut, Andrew; Loman, Nick; Pybus, Oliver; Barclay, Wendy; Barrett, Jeff; Carabelli, Alesandro; Connor, Tom; Peacock, Tom; L. Robertson, David; Vol, Erik (2020). Preliminary genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in the UK defined by a novel set of spike mutations (Report). Written on behalf of COVID-19 Genomics Consortium UK. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Callaway, Ewen (15 January 2021). "'A bloody mess': Confusion reigns over naming of new COVID variants". Nature News & Comment. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00097-w. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

[...] Emma Hodcroft, a molecular epidemiologist at the University of Bern, Switzerland, who is part of Nextstrain, the SARS-CoV-2 naming effort that called the ‘UK variant’ 20I/501Y.V1.

- Chand et al., p. 2.

- "COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2): information about the new virus variant". Gov.uk. Public Health England. 20 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "New coronavirus variant: What do we know?". BBC. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Wise, Jacqui (16 December 2020). "Covid-19: New coronavirus variant is identified in UK". The BMJ. 371: m4857. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4857. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 33328153. S2CID 229291003.

- Chand et al., p. 5.

- "Estimated transmissibility and severity of novel SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern 202012/01 in England". CMMID Repository. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021 – via GitHub.

Cited in European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (21 January 2021). "Risk related to the spread of new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the EU/EEA – first update" (PDF). Stockholm: ECDC. p. 9. Retrieved 24 January 2021. - Leung, Kathy; Shum, Marcus HH; Leung, Gabriel M; Lam, Tommy TY; Wu, Joseph T (7 January 2021). "Early transmissibility assessment of the N501Y mutant strains of SARS-CoV-2 in the United Kingdom, October to November 2020". Eurosurveillance. European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC). 26 (1). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es.2020.26.1.2002106. ISSN 1560-7917. Cited in ECDC (21 January 2021), p. 9.

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport; Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap; Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid (31 January 2021). "98e OMT advies deel 1 - Rapport" [98th OMT advice part 1 - Report]. www.rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Notat om prognoser for smittetal og indlæggelser ved scenarier for genåbning af 0.-4. klasse i grundskolen [Memorandum on forecasts for infection rates and hospital admissions in scenarios for reopening of 0th–4th class in primary school] (PDF) (Report) (in Danish). Statens Serum Institut. 31 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (18 December 2020). "NERVTAG meeting on SARS-CoV-2 variant under investigation: VUI-202012/01".

- Volz, Erik; Mishra, Swapnil; Chand, Meera; Barrett, Jeffrey C.; Johnson, Robert; Geidelberg, Lily; Hinsley, Wes R; Laydon, Daniel J; Dabrera, Gavin; O'Toole, Áine; Amato, Roberto; Ragonnet-Cronin, Manon; Harrison, Ian; Jackson, Ben; Ariani, Cristina V.; Boyd, Olivia; Loman, Nicholas J; McCrone, John T; Gonçalves, Sónia; Jorgensen, David; Myers, Richard; Hill, Verity; Jackson, David K.; Gaythorpe, Katy; Groves, Natalie; Sillitoe, John; Kwiatkowski, Dominic P.; Flaxman, Seth; Ratmann, Oliver; Bhatt, Samir; Hopkins, Susan; Gandy, Axel; Rambaut, Andrew; Ferguson, Neil M (4 January 2021). Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B.1.1.7 in England: Insights from linking epidemiological and genetic data (preprint) (Report). doi:10.1101/2020.12.30.20249034. hdl:10044/1/85239 – via medRxiv.

- "New evidence on VUI-202012/01 and review of the public health risk assessment". Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "COG-UK Showcase Event - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- Grabowski, Frederic; Preibisch, Grzegorz; Kochańczyk, Marek; Lipniacki, Tomasz (4 January 2021). SARS-CoV-2 Variant Under Investigation 202012/01 has more than twofold replicative advantage (Report). doi:10.1101/2020.12.28.20248906 – via medRxiv.

- "UniProtKB - P0DTC2 (SPIKE_SARS2)". UniProt. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "NPHET COVID Update 21st January 2021" (PDF).

- Pylas, Pan (2 January 2021). "U.K. breaks record with 57,725 cases, is urged to keep schools closed". Coronavirus. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Mahase, Elisabeth (23 December 2020). "Covid-19: What have we learnt about the new variant in the UK?". BMJ. 371: m4944. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4944. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 33361120. S2CID 229366003.

- Kirby, Tony (5 January 2021). "New variant of SARS-CoV-2 in UK causes surge of COVID-19". The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00005-9. ISSN 2213-2600. PMID 33417829.

- COG-UK update on SARS-CoV-2 Spike mutations of special interest | Report 1 (PDF) (Report). COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium (COG-UK). 20 December 2020. p. 7.

- COG-UK (20 December 2020), p. 4.

- Yi, C.; Sun, X.; Ye, J.; et al. (2020). "Key residues of the receptor binding motif in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 that interact with ACE2 and neutralizing antibodies". Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 17: 621–630. doi:10.1038/s41423-020-0458-z.

- COG-UK (20 December 2020), p. 1.

- Chand et al., p. 6.

- Galloway, Summer E. (2021). "Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 Lineage — United States, December 29, 2020–January 12, 2021". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 70. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e2. ISSN 0149-2195.

- "Phylogenetic evidence that B.1.1.7 has been circulating in the United States since early- to mid-November". 19 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021 – via Virological.

- "Covid: WHO in 'close contact' with UK over new virus variant". BBC News. 20 December 2020.

- Berger, Miriam (20 December 2020). "Countries across Europe halt flights from Britain over concerns about coronavirus mutation". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- "New UK variant 'may be more deadly'". BBC News. 22 January 2021.

- Peston, Robert (22 January 2021). "New Covid-19 strain may be more lethal, Robert Peston learns". ITV News. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- NERVTAG_paper_on_variant_of_concern__VOC__B.1.1.7.pdf assets.publishing.service.gov.uk

- Zinzula, Luca (2020). "Lost in deletion: The enigmatic ORF8 protein of SARS-CoV-2". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.10.045. PMC 7577707. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Kupferschmidt, Kai (20 December 2020). "Mutant coronavirus in the United Kingdom sets off alarms but its importance remains unclear". Science Mag. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

See also COG-UK (20 December 2020), p. 4: "69-70del has been identified in variants associated with immune escape in immunocompromised patients [...]." - "Rapid evaluation confirms lateral flow devices effective in detecting new COVID-19 variant". GOV.UK. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Patel-Carstairs, Sunita (19 December 2020). "COVID-19: London and South East set for Tier 4 rules - as new COVID variant 'real cause for concern'". Sky News.

- "Covid vaccines 'still effective' against fast-spreading variant". Metro. 20 December 2020.

- "Vaccines effective against new virus strain – German health minister". INQUIRER.net. AFP. 21 December 2020.

- "Genomic overview of SARS-CoV-2 in Denmark". www.covid19genomics.dk Danish Covid-19 Genome Consortium. 30 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- van Dissel, Jaap (20 January 2021). "COVID-1925e Tweede Kamer briefing 20 jan 2021" (PDF). RIVM/ www.tweedekamer.nl. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Borges, Vítor; et al. (19 January 2021). "Tracking SARS-CoV-2 VOC 202012/01 (lineage B.1.1.7) dissemination in Portugal: insights from nationwide RT-PCR Spike gene drop out data". virological.org. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Genomische Charakterisierung" [Genomic characterization]. sciencetaskforce.ch. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Walker, A. Sarah; et al. (15 January 2021). "Increased infections, but not viral burden, with a new SARS-CoV-2 variant". Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey, UK: 29 January 2021: 10. Positive tests that are compatible with the new UK variant". www.ons.gov.uk. 29 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Risk related to spread of new SARSCoV-2 variants of concern in the EU/EEA" (PDF). www.ecdc.europa.eu. 29 December 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Denmark imposes new restrictions over fears of coronavirus variant". Reuters. 5 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Higgins-Dunn, N. (19 December 2020). "The U.K. has identified a new Covid-19 strain that spreads more quickly. Here's what they know". MSNBC.

- "COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium - Wellcome Sanger Institute". www.sanger.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Gallagher, James (20 December 2020). "New coronavirus variant: What do we know?". BBC News. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Ross, T.; Spence, E. (19 December 2020). "London Begins Emergency Lockdown as U.K. Fights New Virus Strain". Bloomberg News.

- "Variants – distribution of cases data: data up to 25 January 2021". Gov.uk. Public Health England. 26 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "Coronavirus Ireland: 52 further deaths and 2,371 new cases of Covid-19 as 'some evidence' UK variant associated with higher death rate". independent. 22 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (21 January 2021). "Risk related to the spread of new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the EU/EEA – first update (21 January 2021)" (PDF). www.ecdc.europa.eu. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Letter from CMO to Minister for Health re COVID-19 (Coronavirus) – 28 January 2021" (PDF). Government of Ireland. Department of Health. 28 January 2021.

- "Portugal to close schools amid surge of UK variant".

- "Senior health official: UK virus variant putting pregnant women at greater risk". www.timesofisrael.com. 21 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "Coronavirus: UK variant causes 25% of new infections in Belgium". The Brussels Times. 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Stickprov tyder på ökad spridning av den brittiska virusvarianten i Sverige" [Random samples indicate an increased spread of the British virus variant in Sweden] (in Swedish). Folkhälsomyndigheten. 2 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Santé Publique France (28 January 2021). "COVID-19: Point épidémiologi que hebdomadaire du 28 janvier 2021" [COVID-19: Weekly epidemiological update of January 28, 2021] (in French). Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Santé Publique France (4 February 2021). "COVID-19: Point épidémiologi que hebdomadaire du 04 février 2021" [COVID-19: Weekly epidemiological update of February 4, 2021] (in French). Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Estimated date of dominance of VOC-202012/01 strain in France and projected scenarios" (PDF). 16 January 2021.

- "Spanish Health Ministry estimates British variant accounts for up to 10% of positives in Spain". murciatoday.com. 30 January 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Galloway, Summer E. (2021). "Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 Lineage — United States, December 29, 2020–January 12, 2021". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 70. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e2. ISSN 0149-2195.

- "Update on the Helix, Illumina surveillance program: B.1.1.7 variant of SARS-CoV-2, first identified in the UK, spreads further into the US". Helix. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- "How far has the UK COVID-19 variant spread and what pace is it moving at?". www.abc.net.au. 10 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- KupferschmidtJan. 5, Kai; 2021; Pm, 3:05 (5 January 2021). "Viral mutations may cause another 'very, very bad' COVID-19 wave, scientists warn". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 10 January 2021.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (16 January 2021). "Advies deel 1 n.a.v. 96e OMT over COVID-19 - Beleidsnota" [Advice part 1 on the basis of 96th OMT on COVID-19 - Policy note]. www.rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (2 February 2021). "Kamerbrief met stand van zaken COVID-19" [Letter to Parliament with the state of affairs COVID-19] (PDF). www.rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Henley, Jon; Jones, Sam; Giuffrida, Angela; Holmes, Oliver (20 December 2020). "EU to hold crisis talks as countries block travel from UK over new Covid strain". The Guardian.

- Hope, Alan (20 December 2020). "Netherlands bans flights from UK over new Covid mutation". The Brussels Times.

- "Coronavirus, in Italia un soggetto positivo alla variante inglese" [Coronavirus, one person tests positive in Italy for the English variant]. la Repubblica (in Italian). 20 December 2020.

- Kelland, Kate (21 December 2020). "Explainer - The new coronavirus variant in Britain: How worrying is it?". Reuters.

- Squires, Nick; Orange, Richard (21 December 2020). "New coronavirus strain detected around the globe, from Gibraltar to Australia". The Telegraph.

- "Singapore confirms first case of new Covid-19 strain from UK, a 17-year-old student who recently returned from Britain". The Straits Times. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- "Israel confirms four cases of new Covid variant". The Guardian. 23 December 2020.

- Moriarty, Gerry (23 December 2020). "First case of UK variant strain of Covid-19 confirmed in Northern Ireland". The Irish Times. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- Burger, Ludwig (24 December 2020). "Germany reports first case of coronavirus variant spreading in Britain". Reuters.

- "COVID-19 : Nouvelle variante du coronavirus découverte dans deux échantillons en Suisse" [COVID-19: New variant of the coronavirus discovered in two samples in Switzerland] (in French). Federal Office of Public Health (Switzerland). 24 December 2020.

- Moloney, Eoghan (25 December 2020). "New UK variant of Covid-19 confirmed in Ireland while 1,025 new cases and two further deaths confirmed". Irish Independent. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- Graham-Harrison, Emma (25 December 2020). "Japan reports five cases of coronavirus variant found in UK". The Guardian.

- "Ontario identifies first cases of COVID-19 U.K. variant in the province". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC News). 26 December 2020.

- "Coronavirus: More cases of new Covid variant found in Europe". BBC. 26 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- "France, Lebanon confirm first cases of new coronavirus variant". Aljazeera. 26 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- "Fall av den brittiska virusvarianten upptäckt i Sverige" [Cases of the British virus variant discovered in Sweden] (in Swedish). SVT. 26 December 2020.

- "Norway, Portugal confirm first cases of coronavirus variant in travellers from the UK". Newshub. 27 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- "Jordan detects two coronavirus variant cases: minister". Gulf News. 27 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- "New UK variant Covid strain detected in Finland". Yle News. 28 December 2020.

- "South Korea reports cases of COVID variant - and says they came from UK". Sky News. 28 December 2020.

- "Chile records first case of British variant of coronavirus - health ministry". Reuters. 29 December 2020.

- "Coronavirus: India confirms six cases of new Covid variant". BBC News. 29 December 2020.

- "First confirmed case of new Covid-19 strain detected in Pakistan". Hindustan Times. 29 December 2020.

- "New Covid strain in UAE: All we know so far". Khaleej Times. 30 December 2020.

- "Three cases of new COVID variant detected in Malta". Times of Malta. 30 December 2020.

- "Taiwan reports its first case of mutant Covid-19 strain found in Britain". South China Morning Post. 30 December 2020.

- "China confirms first case of UK coronavirus variant". France24. 31 December 2020.

- "Brazil detects two cases of new coronavirus variant found in UK". Reuters. 31 December 2020.

- Knudsen, T.H. (20 December 2020). "Dansk Oxford-professor: Danmark skal gøre alt for, at ny virusvariant ikke spreder sig" [Danish Oxford professor: Denmark must do everything to ensure that new virus variant does not spread] (in Danish). DR.

See also: "Global sequencing coverage". covidcg.org. Retrieved 23 December 2020. - Mandavilli, Apoorva; Landler, Mark; Castle, Stephen (20 December 2020). "Scientists urge calm about coronavirus mutations, which are not unexpected". New York Times.

- Casiano, Louis (29 December 2020). "Colorado health officials confirm new COVID-19 variant in the state". Fox News. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Nedelman, Michael (6 January 2021). "CDC has found more than 50 US cases of coronavirus variant first identified in UK". CNN. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Reimann, Nicholas (8 January 2021). "'Close To A Worst-Case Scenario'—Former CDC Director Issues 'Horrifying' Outlook For New Covid Strain". Forbes. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Son dakika haberi... Bakan Koca açıkladı, 15 kişide mutasyonlu virüs! İngiltere'den girişler tamamen durduruldu" [Breaking news... Minister Koca announced, mutated virus in 15 people! Entries from the UK are completely suspended] (Video). CNN Türk. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "SSI: Meget smitsom coronamutation fra England spreder sig i Danmark" [SSI: Very infectious corona mutation [sic] from England spreads in Denmark]. DR (in Danish). 2 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "Udvikling i smitte med engelsk virusvariant af SARS-COV-2 (cluster B.1.1.7)" [Development in infection with English virus variant of SARS-COV-2 (cluster B.1.1.7)] (PDF) (in Danish). Statens Serum Institut. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- "Status for udvikling af B.1.1.7 i Danmark d. 17. januar 2021" [Status for progression of B.1.1.7 in Denmark on 17 January 2021]. Statens Serum Institut. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "Vietnam reports first case of new coronavirus variant in woman returning from Britain". The Telegraph. 2 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- "New Covid-19 strain found in Luxembourg". luxtimes.lu. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Greece detects four cases of new coronavirus variant". Reuters. 3 January 2021.

- "Four cases of COVID-19 variant confirmed in Jamaica". 3 January 2021.

- Turner, Katy. "Coronavirus: New, fast-spreading British variant found in Cyprus | Cyprus Mail". Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Six cases at NZ border have had new Covid-19 variant, 19 cases in total in the past three days". Retrieved 4 January 2021 – via TVNZ.

- The Thaiger (3 January 2021). "Britons arriving in Thailand test positive for Covid UK variant". The Thaiger. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Georgia confirms first case of UK-linked coronavirus strain". 4 January 2021.

- "British, South African corornavirus mutations detected in Austria". Reuters. Berlin. 4 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- "Iran confirms first case of new Covid-19 variant". France 24. Tehran. 5 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- "Oman registers first case of new virus variant in traveller from UK". Dubai. Reuters. 5 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- "Cases of the new UK coronavirus variant have been confirmed in Slovakia". Expats.cz. 5 January 2021.

- "Romania detects first case of British coronavirus variant". Reuters. 8 January 2021.

- "Peru Confirms First Case of COVID-19 Variant Strain". 9 January 2021.

- Mexico detects first case of new coronavirus strain first seen in UK, 11 January 2021 www.business-standard.com, accessed 15 January 2021

- "UK-variant of Covid-19 has reached Malaysia, Dr Noor Hisham confirms". Malay Mail. 11 January 2021.

- "New Covid-19 variant found in Latvia". Baltic News Network. 4 January 2021.

- "Ecuador records first case of new coronavirus variant". 12 January 2021.

- CNN Philippines Staff (13 January 2021). "LIVE UPDATES: COVID-19 pandemic". cnnphilippines.com. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Hungary detects UK variant of coronavirus, surgeon general says". Reuters. 13 January 2021.

- "Gambia records first two cases of British COVID-19 variant". Reuters. 14 January 2021.

- "New COVID-19 strain confirmed to arrive in Dominican Republic from London". 15 January 2021.

- "Argentina detects first case of British virus variant". MedicalXpress. 16 January 2021.

- "UPDATE 1-Czech Republic detects UK coronavirus variant, to maintain lockdown measures". Reuters. 18 January 2021.

- "Kuwait, Morocco report first cases of UK coronavirus variant". The Arab Weekly. 19 January 2021.

- "Kuwait registers first cases of new virus variant". Reuters. 19 January 2021.

- Adebowale, Nike (25 January 2021). "Updated: COVID-19 variant, causing anxiety in UK, found in Nigeria – Official". The Premium Times. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "UPDATE 1-Senegal confirms presence of UK variant of coronavirus". Reuters. 28 January 2021.

- "Detectaron la variante británica del virus SARS-CoV-2 en Uruguay" (in Spanish). 4 February 2021.

- "Municipality to test 60,000 residents for British strain of coronavirus". DutchNews. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- Miller, Devon. "COVID-19 U.K. Variant Confirmed In Los Angeles County". The Valley Post. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Expert reaction new restrictions and the new SARS-CoV-2 variant". Science Media Centre. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "Return to full lockdown might not be enough to control new Covid variant, Sage warns". The Independent. 31 December 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Covid-19: Christmas rules tightened for England, Scotland and Wales". BBC News. 20 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Fairnie, Robert (19 December 2020). "Travel between Scotland and rest of UK banned over Christmas as border is closed". edinburghlive. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Halliday, Josh (21 December 2020). "Calls for national lockdown in England to curb spread of new Covid strain". The Guardian.

- Henley, Jon; Jones, Sam; Giuffrida, Angela; Holmes, Oliver (20 December 2020). "EU to hold crisis talks as countries block travel from UK over new Covid strain". The Guardian.

- Michaels, Daniel (20 December 2020). "Countries Ban Travel From U.K. in Race to Block New Covid-19 Strain". WSJ.

- "Kent lorry queue down to 60 vehicles after border closure". www.bbc.co.uk. 29 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- GRIESHABER, KIRSTEN; HUI, SYLVIA (21 December 2020). "More EU nations ban travel from UK, fearing virus variant". AP NEWS.

- Berger, Miriam (20 December 2020). "Countries across Europe halt flights from Britain over concerns about coronavirus mutation". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Quinn, Edna Mohamed(now) Ben; Davies (earlier), Caroline; Davidson, Helen; Wahlquist (earlier), Calla; Walker, Shaun (20 December 2020). "Cases of new strain reported outside of UK – as it happened". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "Covid-19: UK isolation grows as more countries ban travel". BBC News. 21 December 2020.

- Ogura, Junko. "Japan will ban entry to foreign nationals after Covid-19 variant detected in country". CNN. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- "California has nation's 2nd confirmed case of virus variant". AP NEWS. 30 December 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Mallapaty, Smriti (22 December 2020). "What the data say about border closures and COVID spread". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03605-6. PMID 33361805. S2CID 229692296.

External links

- Corum, Jonathan; Zimmer, Carl (18 January 2021). "Inside the B.1.1.7 Coronavirus Variant". The New York Times.

- Public Health England: Variants: UK distribution – summary of 4 nations distribution

- PANGO lineages: New Variant Report - Report on global distribution of lineage B.1.1.7