Vasil Adzhalarski

Vasil Stoyanov Staykov (December 24, 1880 – November 14, 1909) known as Vasil Adzhalarski, was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary,[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] an Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) leader of revolutionary bands in the regions of Skopje and Kumanovo.

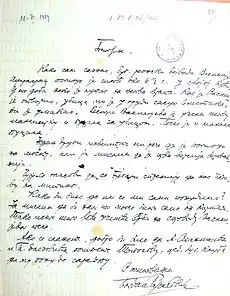

Vasil Adzhalarski | |

|---|---|

Photograph of Vasil Adzhalarski | |

| Born | December 24, 1880 |

| Died | November 14, 1909 (aged 28) |

| Organization | IMARO |

Biography

Vasil Stoyanov was born in 1880 in the village of Adzhalari, in the Sanjak of Üsküp of the Kosovo Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia). He received his nickname after this village, which is now known as Miladinovci. In 1901 he moved with his family in Skopje. He entered IMARO and realized a series of tasks for the Organization – he carried post, hid and purchased weapons, but he was arrested and spent two years in the prison Kuršumli An. He got released after an amnesty. In 1903, he became an illegal freedom fighter and at first he was an assistant of the band leader Sande Čolakot in Kumanovo. Later, he entered the revolutionary band of Bobi Stoychev and after that he himself became a leader, in the regions of Skopska Crna Gora and Blatija, under the supervision of Dame Martinov. Adzhalarski distinguished himself from the other freedom fighters with the assassination of several Muslim beys who were suppressing the local Bulgarian inhabitants.[11]

In 1905, Vasil Adzhalarski became a regional leader of the Skopje region. From the end of 1904 until 1908 his revolutionary band conducted more than 10 massive battles with the Turkish military. Adzhalarski also took several successful actions against the armed Serbian propaganda. As a response to the murders of seven Macedonians from the Chair neighborhood by a Serbian band, he killed 9 Serbomans in Brodec, after which the Serbian bands ceased this type of actions. In February 1907, he burned the Han in the village of Sopishte, that served as a base for the traverse of the Serbian bands to the region of Porece.[11]

After the Young Turk Revolution in 1908, he was no more a freedom fighter, but he was killed in an ambush by the Ottoman authorities in Skopje in 1909.[12] His funeral was a reason for a massive protests by the Macedonians from the region of Skopje against the authorities.

In 1918, Ivan Snegarov wrote the following about Vasil Adzhalarski:

He possessed all physical and spiritual qualities, necessary for fascinating agitation and attraction of the crowds. He was tall, stalwart, well-built… brisk and smart, determined in his actions and fearless in the fight, tireless in his deeds and impossible to catch, he undoubtedly stood before the imagination of the people as the old knights, and inspired them to create heroic epos. If we additionally mention that he was eloquent and had a phenomenal memory…, we will be able to imagine thoroughly the secret of the power of the local Organization in his time and the attraction with which the Bulgarians from Skopje still mention his name.[11]

Literature

- "Две надгробни речи; След убийството на Васил Аджаларски; Подробности по убийството на войводата Васил Стоянов", публикувано во "Вести", книга 34, 35, 40, Цариград, 1909 г. The Istanbul Exarchist newspaper "Vesti" about the murder of Vasil Adzhalarski by the Turkish authorities (in Bulgarian) .

References

- Николов, Борис Й. Вътрешна македоно-одринска революционна организация. Войводи и ръководители (1893 – 1934). Биографично-библиографски справочник, София, 2001, стр. 24 -25.

- Георгиев, Величко, Стайко Трифонов, История на българите 1878 – 1944 в документи, том 1 1878 – 1912, част втора, стр. 475 – 481., „Българските революционни чети в Македония според доклад на А. Тошев до министъра на външните работи и изповеданията Д. Станчов“.

- Initially the membership in the IMRO was restricted only for Bulgarians. Its first name was "Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees", which was later changed several times. IMRO was active not only in Macedonia but also in Thrace (the Vilayet of Adrianople). Since its early name emphasized the Bulgarian nature of the organization by linking the inhabitants of Thrace and Macedonia to Bulgaria, these facts are still difficult to be explained from the Macedonian historiography. They suggest that IMRO revolutionaries in the Ottoman period did not differentiate between ‘Macedonians’ and ‘Bulgarians’. Moreover, as their own writings attest, they often saw themselves and their compatriots as ‘Bulgarians’. All of them wrote in standard Bulgarian language. For more see: Brunnbauer, Ulf (2004) Historiography, Myths and the Nation in the Republic of Macedonia. In: Brunnbauer, Ulf, (ed.) (Re)Writing History. Historiography in Southeast Europe after Socialism. Studies on South East Europe, vol. 4. LIT, Münster, pp. 165-200 ISBN 382587365X.

- The revolutionary committee dedicated itself to fight for "full political autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople." Since they sought autonomy only for those areas inhabited by Bulgarians, they denied other nationalities membership in IMRO. According to Article 3 of the statutes, "any Bulgarian could become a member". For more see: Laura Beth Sherman, Fires on the mountain: the Macedonian revolutionary movement and the kidnapping of Ellen Stone, Volume 62, East European Monographs, 1980, ISBN 0914710559, p. 10.

- During the 20th century, Slavo-Macedonian national feeling has shifted. At the beginning of the 20th century, Slavic patriots in Macedonia felt a strong attachment to Macedonia as a multi-ethnic homeland. They imagined a Macedonian community uniting themselves with non-Slavic Macedonians... Most of these Macedonian Slavs also saw themselves as Bulgarians. By the middle of the 20th. century, however Macedonian patriots began to see Macedonian and Bulgarian loyalties as mutually exclusive. Regional Macedonian nationalism had become ethnic Macedonian nationalism... This transformation shows that the content of collective loyalties can shift.Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Ethnologia Balkanica Series, Klaus Roth, Ulf Brunnbauer, LIT Verlag Münster, 2010, p. 127., ISBN 3825813878

- Up until the early 20th century and beyond, the international community viewed Macedonians as regional variety of Bulgarians, i.e. Western Bulgarians.Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe, Geographical perspectives on the human past : Europe: Current Events, George W. White, Rowman & Littlefield, 2000, ISBN 0847698092, p. 236.

- "However, contrary to the impression of researchers who believe that the Internal organization espoused a "Macedonian national consciousness," the local revolutionaries declared their conviction that the "majority" of the Christian population of Macedonia is "Bulgarian." They clearly rejected possible allegations of what they call "national separatism" vis-a-vis the Bulgarians, and even consider it "immoral." Though they declared an equal attitude towards all the "Macedonian populations." Tschavdar Marinov, We the Macedonians, The Paths of Macedonian Supra-Nationalism (1878–1912), in "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe" with Mishkova Diana as ed., Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, pp. 107-137.

- "The IMARO activists saw the future autonomous Macedonia as a multinational polity, and did not pursue the self-determination of Macedonian Slavs as a separate ethnicity. Therefore, Macedonian was an umbrella term covering Greeks, Bulgarians, Turks, Vlachs, Albanians, Serbs, Jews, and so on." Bechev, Dimitar. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, Introduction.

- The political and military leaders of the Slavs of Macedonia at the turn of the century seem not to have heard the call for a separate Macedonian national identity; they continued to identify themselves in a national sense as Bulgarians rather than Macedonians.[...] (They) never seem to have doubted "the predominantly Bulgarian character of the population of Macedonia". "The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world", Princeton University Press, Danforth, Loring M. 1997, ISBN 0691043566, p. 64.

- The modern Macedonian historiographic equation of IMRO demands for autonomy with a separate and distinct national identity does not necessarily jibe with the historical record. A rather obvious problem is the very title of the organization, which included Thrace in addition to Macedonia. Thrace whose population was never claimed by modern Macedonian nationalism...There is, moreover, the not less complicated issue of what autonomy meant to the people who espoused it in their writings. According to Hristo Tatarchev, their demand for autonomy was motivated not by an attachment to Macedonian national identity but out of concern that an explicit agenda of unification with Bulgaria would provoke other small Balkan nations and the Great Powers to action. Macedonian autonomy, in other words, can be seen as a tactical diversion, or as “Plan B” of Bulgarian unification. İpek Yosmaoğlu, Blood Ties: Religion, Violence and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908, Cornell University Press, 2013, ISBN 0801469791, pp. 15-16.

- Снегаров, Иван. Васил Аджарларски, Родина (Скопие), г. ІІІ, бр. 660, 8 юли 1918, с. 2-3.

- Енциклопедия България, том 1, Издателство на БАН, София, 1978.