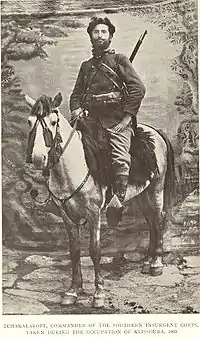

Vasil Chekalarov

Vasil Hristov Chekalarov (Bulgarian: Васил Христов Чекаларов) or Vasil Tcakalarov (22.02.1874 in Smardesh, Ottoman Empire, today Krystallopigi, Florina regional unit, Greece – July 9, 1913 in Belkamen, today Drosopigi, Florina regional unit) was a Bulgarian[1] revolutionary and one of the leaders of Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organisation in Macedonia. H. N. Brailsford described Chekalarov as the "cruel but competent general" of the Bulgarian insurgents in Macedonia.[2] Despite his Bulgarian self-identification,[3] per post-WWII Macedonian historiography he was an ethnic Macedonian.[4][5][6]

He was a leading komitaji in the bands of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees and took part in the battles against the Ottoman authorities as well before the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising as after it. In 1901-1902 he created a channel for illegal purchase and transfer of firearms from Greece to Southern Macedonia. In 1904 he migrated into Bulgaria and became one of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) organizers of the military campaign against the Greek Struggle for Macedonia.

As a commander of a Bulgarian guerilla band, Chekalarov supported the Greek army in the First Balkan War 1912-1913.[7] Later he fought on the side of the Bulgarian Army on the front in Eastern Thrace in the composition of the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps. He was killed by Greek troops during the Second Balkan War and his head was publicly displayed in Florina.

In 1934 a Bulgarian village was renamed Chakalarovo in honor of Vasil Chekalarov.[8]

External links

- Chekalarov, Vasil. Diary 1901-1903, Sofia 2001 (in Bulgarian)

- A folk song about Vasil Chakalarov at YouTube

- Лазар Поптрайков - "Въстанието в Костурско; от 20 юлий до 30 август вкл.", публикувано в "Бюлетин на в. Автономия; Задграничен лист на Вътрешната македоно-одринска организация", брой 44-47, София, 1903 година Report about the Ilinden uprising written by Lazar Poptrajkov, Vasil Chakalarov, Manol Rozov, Pando Klyashev and Mihail Nikolov

References

- Vacalopoulos, Apostolos. Modern history of Macedonia (1830-1912), Thessaloniki 1988, p. 192

- Brailsford, H. N. Macedonia: Its Races and Their Future, London 1906, p. 145

- Чекаларов, Васил. Дневник 1901-1903, София 2001, с. 91, 122, 140, 188, 197 (Chekalarov, Vasil. Diary 1901-1903, Sofia 2001, p. 91, 122, 140, 188, 197)

- The origins of the official Macedonian national narrative are to be sought in the establishment in 1944 of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. This open acknowledgment of the Macedonian national identity led to the creation of a revisionist historiography whose goal has been to affirm the existence of the Macedonian nation through the history. Macedonian historiography is revising a considerable part of ancient, medieval, and modern histories of the Balkans. Its goal is to claim for the Macedonian peoples a considerable part of what the Greeks consider Greek history and the Bulgarians Bulgarian history. The claim is that most of the Slavic population of Macedonia in the 19th and first half of the 20th century was ethnic Macedonian. For more see: Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0275976483, p. 58; Victor Roudometof, Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question in Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 (1996) 253-301.

- Yugoslav Communists recognized the existence of a Macedonian nationality during WWII to quiet fears of the Macedonian population that a communist Yugoslavia would continue to follow the former Yugoslav policy of forced Serbianization. Hence, for them to recognize the inhabitants of Macedonia as Bulgarians would be tantamount to admitting that they should be part of the Bulgarian state. For that the Yugoslav Communists were most anxious to mold Macedonian history to fit their conception of Macedonian consciousness. The treatment of Macedonian history in Communist Yugoslavia had the same primary goal as the creation of the Macedonian language: to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate national consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia. For more see: Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- The past was systematically falsified to conceal the fact that many prominent ‘Macedonians’ had supposed themselves to be Bulgarians, and generations of students were taught the pseudo-history of the Macedonian nation. The mass media and education were the key to this process of national acculturation, speaking to people in a language that they came to regard as their Macedonian mothertongue, even if it was perfectly understood in Sofia. For more see: Michael L. Benson, Yugoslavia: A Concise History, Edition 2, Springer, 2003, ISBN 1403997209, p. 89.

- Силянов, Христо. От Витоша до Грамос. Пътят на една чета през Освободителната война 1912, София 1920, Македоно-Одринско опълчение 1912-1913. Личен състав по документите на Дирекция "Централен военен архив", София 2006, с. 794, 892.

- Мичев, Николай, Петър Коледаров. Речник на селищата и селищните имена в България 1878-1987, София, 1989, стр. 68.