Vector clock

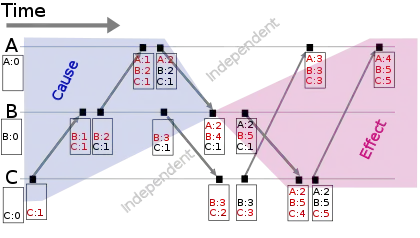

A vector clock is a data structure used for determining the partial ordering of events in a distributed system and detecting causality violations. Just as in Lamport timestamps, interprocess messages contain the state of the sending process's logical clock. A vector clock of a system of N processes is an array/vector of N logical clocks, one clock per process; a local "smallest possible values" copy of the global clock-array is kept in each process, with the following rules for clock updates:

- Initially all clocks are zero.

- Each time a process experiences an internal event, it increments its own logical clock in the vector by one.

- Each time a process sends a message, it increments its own logical clock in the vector by one (as in the bullet above, but not twice for the same event) and then sends a copy of its own vector.

- Each time a process receives a message, it increments its own logical clock in the vector by one and updates each element in its vector by taking the maximum of the value in its own vector clock and the value in the vector in the received message (for every element).

History

Without using the specific name "vector clock", the concept of a vector clock was first mentioned[1] in a 1986 paper by Rivka Ladin and Barbara Liskov where they use the term "multipart timestamp".[2] To quote from page 31 of the Liskov/Ladin paper:

We solve this problem by using multipart timestamps, where there is one part for each replica. Thus, if there are n replicas, a timestamp t is

t = <t1, …, tn>where each part is a positive integer. Since there will typically be a small number of replicas (e.g., 3 to 7), using such a timestamp is practical.

The term "vector clock" was first used independently by Colin Fidge and Friedemann Mattern in 1988.[3][4]

Partial ordering property

Vector clocks allow for the partial causal ordering of events. Defining the following:

- denotes the vector clock of event , and denotes the component of that clock for process .

-

- In English: is less than , if and only if is less than or equal to for all process indices , and at least one of those relationships is strictly smaller (that is, ).

- denotes that event happened before event . It is defined as: if , then

Properties:

- Antisymmetry: if , then ¬

- Transitivity: if and , then or if and , then

Relation with other orders:

- Let be the real time when event occurs. If , then

- Let be the Lamport timestamp of event . If , then

Other mechanisms

- In 1999, Torres-Rojas and Ahamad developed Plausible Clocks,[5] a mechanism that takes less space than vector clocks but that, in some cases, will totally order events that are causally concurrent.

- In 2008, Almeida et al. introduced Interval Tree Clocks.[6][7][8] This mechanism generalizes Vector Clocks and allows operation in dynamic environments when the identities and number of processes in the computation is not known in advance.

- In 2019, Lum Ramabaja developed Bloom Clocks, [9] a probabilistic data structure whose space complexity does not depend on the number of nodes in a system. If two clocks are not comparable, the bloom clock can always deduce it, i.e. false negatives are not possible. If two clocks are comparable, the bloom clock can calculate the confidence of that statement, i.e. it can compute the false positive rate between comparable pairs of clocks.

References

- The reference to this paper was discovered by Prof Lindsey Kuper and described in lecture 23 of her YouTube video lecture series on Distributed Systems

- Barbara Liskov, Rivka Ladin (1986). "Highly-Available Distributed Services and Fault-Tolerant Distributed Garbage Collection". ACM. pp. 29–39. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- Colin J. Fidge (February 1988). "Timestamps in Message-Passing Systems That Preserve the Partial Ordering" (PDF). In K. Raymond (ed.). Proc. of the 11th Australian Computer Science Conference (ACSC'88). pp. 56–66. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- Mattern, F. (October 1988), "Virtual Time and Global States of Distributed Systems", in Cosnard, M. (ed.), Proc. Workshop on Parallel and Distributed Algorithms, Chateau de Bonas, France: Elsevier, pp. 215–226

- Francisco Torres-Rojas; Mustaque Ahamad (1999), "Plausible clocks: constant size logical clocks for distributed systems", Distributed Computing, 12 (4): 179–195, doi:10.1007/s004460050065

- Almeida, Paulo; Baquero, Carlos; Fonte, Victor (2008), "Interval Tree Clocks: A Logical Clock for Dynamic Systems", in Baker, Theodore P.; Bui, Alain; Tixeuil, Sébastien (eds.), Principles of Distributed Systems (PDF), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 5401, Springer-Verlag, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 259–274, Bibcode:2008LNCS.5401.....B, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-92221-6, ISBN 978-3-540-92220-9

- Almeida, Paulo; Baquero, Carlos; Fonte, Victor (2008), "Interval Tree Clocks: A Logical Clock for Dynamic Systems", Interval Tree Clocks: A Logical Clock for Dynamic Systems, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 5401, p. 259, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-92221-6_18, hdl:1822/37748, ISBN 978-3-540-92220-9

- Zhang, Yi (2014), "Background Preliminaries: Interval Tree Clock Results", Background Preliminaries: Interval Tree Clock Results (PDF)

- Lum Ramabaja (2019), The Bloom Clock, arXiv:1905.13064, Bibcode:2019arXiv190513064R

External links

- Why Logical Clocks are Easy (Compares Causal Histories, Vector Clocks and Version Vectors)

- Explanation of Vector clocks

- Timestamp-based vector clock implementation in Erlang

- Vector clock implementation in Objective-C

- Vector clock implementation in Erlang

- Why Vector Clocks are Hard

- Why Cassandra doesn’t need vector clocks