Viktor Dankl von Krasnik

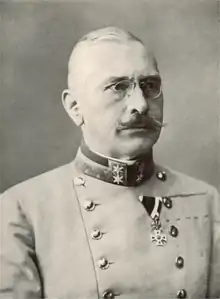

Viktor Julius Ignaz Ferdinand Graf[1] Dankl von Krásnik (Born as Viktor Dankl; 18 September 1854 – 8 January 1941) was a highly decorated Austro-Hungarian officer who reached the pinnacle of his service during World War I with promotion to the rare rank of Colonel General (Generaloberst). His successful career met an abrupt end in 1916 due to both his performance on the Italian front and health issues. After the war, he would be a vocal apologist for both his country's war record and the dethroned Habsburg monarchy.

Viktor Dankl von Krásnik | |

|---|---|

Count Viktor Dankl von Krásnik | |

| Born | 18 September 1854 Weiden in Friaul, Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, Austrian Empire (present-day Udine, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Italy) |

| Died | 8 January 1941 (aged 86) Innsbruck, Reichsgau Tirol-Vorarlberg, Nazi Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1874–1918 |

| Rank | Generaloberst |

| Battles/wars | First World War |

| Awards | Military Order of Maria Theresa |

Early life & career

Viktor Krasnik was born in the then Imperial Austrian Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia (dissolved in 1866 and since 1919 in Italy). His father was a Captain in the army from nearby Venice. His secondary education would first take place in Görz (now Gorizia), where his family relocated after his father's retirement, and then in Triest (now Trieste). Both schools were German language Gymnasiums. In 1869, at the age of fourteen, he moved on to the Cadet Institute at St. Pölten, Lower Austria. From 1870 until 1874 he attended the Theresian Military Academy at Wiener-Neustadt, also in Lower Austria.

Upon completion of the academy, Krasnik was assigned to the Third Dragoon Regiment as a Second Lieutenant. After completion of the War School in Vienna, he became a general staff officer in 1880. For the next two decades, he rose through the officer ranks, becoming the head of the central office of the Austro-Hungarian general staff in 1899. In 1903 he was promoted to the rank of major general and given command of the Sixty-sixth Infantry Brigade in Trieste. From 1905 until 1907 he would head up the Sixteenth Infantry Brigade, also in Trieste. After being promoted to a lieutenant Field Marshal (Feldmarschalleutnant), Krasnik would receive command of the Thirty-sixth Division in Zagreb until 1912, at which point he was moved to Innsbruck to command the Fourteenth Corps. Later that same year, on October 29, Krasnik was elevated to the rank of General of Cavalry.

Service during World War I

At the beginning of war in summer 1914, Krasnik was put in command of the Austro-Hungarian First Army. That August the First Army, along with the Fourth Army, would compose the northwestern flank of Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf’s, push towards Russian forces in Russian Poland and the Galicia region. On August 22, after crossing the San River, Krasnik's army would engage the Russian Fourth Army at the Austro-Hungarian town of Kraśnik. The ensuing battle of Kraśnik ended three days later with Dankl victorious and the Russian Fourth Army retreating back towards the city of Lublin in Russian territory. Krasnik pursued his opponents after the battle but was ultimately forced to withdraw after a series of defeats further southeast along the Austro-Hungarian lines in the largescale battle of Galicia. For his victory at Kraśnik, the first for Austria-Hungary in the war, Krasnik would later be decorated with the Commander's Cross of the Military Maria Theresa Order on August 17, 1917 (see below). Krasnik experienced a good deal of fame and popularity after the battle, becoming something of a national hero until his once rising star would be tarnished by setbacks later on in the war.

After being driven back by Russian forces Krasnik and his First Army were part of a renewed offensive in October 1914 that was undertaken with the German forces to the north and west. Gains made during this drive proved to be only temporary as more or less of a stalemate developed in Dankl's area. The First Army did not see much action during the winter of 1914-15 and were held as reserves for more active Carpathian part of the front further east. During the following spring Krasnik would lead his third and final offensive with the First Army. The Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive in May 1915 enjoyed early success and Dankl's First Army had once again achieved an advance. However, his renewed success would be cut short by a loss at the battle of Opatów which stalled any further push.

On May 23, 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary and Dankl was soon reassigned to the resulting new front in Austria-Hungary's southwest. He would be made commander-in-chief of the defense of Tyrol, his headquarters in Bolzano. Like much of the Austro-Hungarian Army during the war, the forces under his command were poorly supplied and had inferior equipment. Furthermore, they were outnumbered. Throughout the remainder of 1915 and into early 1916, Dankl was able to hold the line, halting numerous Italian attempts to break through into Austria-Hungary. This bought important time for the front to be reinforced. His forces were able to overcome their disadvantages due to their often superior leadership and experience.

In March 1916 Krasnik was given command of the Eleventh Army and on May 1 he was promoted to colonel general. Later that month he would be part of the Asiago offensive, a plan masterminded by Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, the architect of the 1914 Austro-Hungarian advance in Galicia. Krasnik and the Eleventh Army were assigned the critical task of making an initial breakthrough that could be exploited by additional reinforcements (the Third Army). The attack commenced on May 15 and initially, Krasnik was quite successful. He managed to cut through the first and second Italian lines and move south of Rovereto to the Posino Valley. On May 20 this surge stalled due to the inability of artillery to negotiate the treacherous snowy mountain roads. It was not until June that the Austro-Hungarians were able to try a largescale advance. By this time the Italians had regrouped and some Austro-Hungarian forces were siphoned off to the Eastern Front. As a result, a stalemate set in. Once again Krasnik had produced an impressive advance that would prove to be short-lived. His role in the offensive would prove to be his undoing as a combat commander and he would be sidelined for the remainder of the war.

Resignation, later career, and retirement

Dankl was criticized both by Army Group Command (Archduke Eugen) and by the Austro-Hungarian Supreme Command (Conrad). He had ignored an order given by Archduke Eugen to advance at a faster pace, disregarding the lack of artillery. How much Dankl's slow and steady style contributed to the stalling of the Asiago offensive is debatable. These charges and complaints, coupled with his very real health problems, caused the general to send a letter of resignation. On June 17, 1916 he was dismissed from command. His Eleventh Army chief of staff, Major General Pichler, was also relieved of his position.

After undergoing an operation on his throat, specifically a goitre, he was assigned command of the First Arcièren-Leibgarde, part of the Imperial Guards, on January 21, 1917. Dankl rose to commander-in-chief of the Imperial Guards in February 1918 until he was replaced at that post by Conrad, his former superior officer during his time at the front, the following summer. He returned to the First Arcieren-Leibgarde, where he remained until the end of the Habsburg rule over Austria-Hungary. He was retired from the army on December 1, 1918 and moved to Innsbruck.

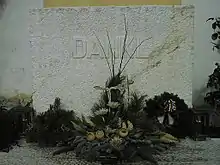

In 1925 Dankl would assume the chancellorship of the Maria Theresa Order. This time he would be replacing a position held by Conrad, who left the vacancy upon his death that year. For the next six years he would be in charge of decorating Austro-Hungarian soldiers from World War I. He undertook this task with much enthusiasm, becoming an outspoken apologist of not only his fellow veterans but of Austria-Hungary in general. He even went so far as to advocate the return of the monarchy, putting himself at odds with the growing support of Austrian Nazi groups for Hitler and Germany. He was a firm opponent of the Anschluss, favoring an Imperial Austria under Habsburg to a Nazi German Reich under Hitler until the end. He refused totalitarianism, fascism, antisemitism and the Second World War. By the time of his death he was seen as a stark anachronism, out of step with the new era of the Greater German Reich. On January 8, 1941, Viktor Dankl died at the age of eighty-six. His wife had died a mere three days earlier. He was buried in the churchyard of Wilten Basilica in Innsbruck and his grave can still be visited. Due to his well-known anti-Nazi stance, the Wehrmacht was ordered not to honor Dankl with any sort of military ceremony.

Honors and decorations

_%E2%80%93_Gerd_Hru%C5%A1ka.png.webp)

Throughout his mostly distinguished career, Dankl was the recipient of a large amount of military and non-military awards. Despite his reputation as being somewhat short tempered, he was noted as one of Austria-Hungary's finer generals of World War I by Conrad.

On August 17, 1917 Dankl was decorated with the Commander's Cross of the Military Maria Theresa Order in recognition of his services during the battle of Kraśnik. In accordance with the statutes of this order, Dankl became a baron in his country's nobility and was since styled "Freiherr von Dankl". In 1918, Emperor Charles I further advanced him to the degree of count and granted him the territorial title of "Kraśnik", after which he was styled "Graf Dankl von Krasnik". This makes Dankl a rare example of a person in Austria who was born a commoner but rose to the title of count. In 1925, he was appointed as Chancellor of the Military Order of Maria Theresa as a successor to Conrad.

His military awards include: the Commander's Cross of the Military Maria Theresa Order, the Grand Cross of the Order of Leopold with War Decoration, the Military Merit Cross First Class with War Decoration, the German Iron Cross of 1914, First and Second Class, the Marianer Cross of the Teutonic Order, and the Star of the Decoration for Services to the Red Cross with war decoration.

Civilian honors include an honorary PhD from an Innsbruck University in philosophy, the naming of a "Dankl" street in Innsbruck and honorary membership in the German Student Corps Danubia Graz.

Notes

Regarding personal names: Until 1919, Graf was a title, translated as Count, not a first or middle name. The female form is Gräfin. In Germany since 1919, it forms part of family names.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- Spencer Tucker (2 September 2003). Who's Who in Twentieth Century Warfare. Routledge. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-134-56515-3.

- Spencer C. Tucker (28 October 2014). World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. pp. 442–. ISBN 978-1-85109-965-8.

- Spencer C. Tucker; Priscilla Mary Roberts (September 2005). Encyclopedia Of World War I: A Political, Social, And Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 334–. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Viktor Dankl von Krasnik. |