War Plan Red

War Plan Red, also known as the Atlantic Strategic War Plan, was one of the color-coded war plans created by the United States Department of War during the interwar period of 1919–1939 to estimate the requirements for a hypothetical war with the British Empire (the "Red" forces). Many different war plans were routinely prepared by mid-level officers primarily as training exercises in how to calculate the logistical and manpower requirements of fighting a war,[1] and War Plan Red outlined those steps necessary to defend against any attempted invasion of the United States from British forces. It further discussed fighting a two-front war with both Japan and Great Britain simultaneously (as envisioned in War Plan Red-Orange).

| War Plan Red | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

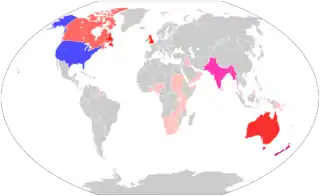

War Plan Red was a plan for the United States to make war with the British Empire. "Blue" indicated the United States while "Red" indicated the British Empire, whose territories were given their own different shades of red: Britain (Red), Newfoundland (Red), Canada (Crimson), India (Ruby), Australia (Scarlet), New Zealand (Garnet), and other areas shaded in pink which were not part of the plan. Ireland, at the time a free state within the British Empire, was named "Emerald" in green. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

War Plan Red was developed by the War Department after the 1927 Geneva Naval Conference and approved in May 1930 by Secretary of War Patrick J. Hurley and Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams III and updated in 1934–35. It was a routine hypothetical exercise and did not require presidential or congressional approval. Only the Congress has the power to declare war.[2]

In 1939, on the outbreak of World War II, a decision was taken that no further planning was required but for the plan to be retained.[3] War Plan Red was not declassified until 1974.

The war plan outlined actions that would be necessary if, for any reason, the US and Britain went to war with each other. The plan assumed that the British would initially have the upper hand by virtue of the strength of the Royal Navy. The plan further assumed that Britain would probably use its base in Canada as a springboard from which to initiate an invasion of the United States. The assumption was taken that at first, the US would fight a defensive battle against invading British forces, but the US would eventually defeat the British by blockading Canada’s ports and cutting off its food supplies. It is debated whether this would have been successful however and if the plan would have ultimately resulted in a stalemate.[4] That was the strategy employed by Britain against the US in the War of 1812.

Outline

War Plan Red first set out a description of Canada's geography, military resources, and transportation and went on to evaluate a series of possible pre-emptive American campaigns to invade Canada in several areas and occupy key ports and railways before British troops could provide reinforcement to the Canadians—the assumption being that Britain would use Canada as a staging point. The idea was that US attacks on Canada would prevent Britain from using Canadian resources, ports, or airbases.[2]

A key move was a joint US Army-Navy attack to capture the port city of Halifax, cutting off the Canadians from their British allies. Their next objective was to "seize Canadian Power Plants near Niagara Falls."[5] This was to be followed by a full-scale invasion on three fronts: from Vermont to take Montreal and Quebec, from North Dakota to take over the railhead at Winnipeg, and from the Midwest to capture the strategic nickel mines of Ontario. In parallel, the US Navy was to seize the Great Lakes and blockade Canada's Atlantic and Pacific ports.[2]

Zones of operation

The main zones of operation discussed in the plan are:

- Nova Scotia and New Brunswick:

- Occupying Halifax would deny the Royal Navy a major base and cut links between Britain and Canada.

- The plan considers several land and sea options for the attack and concludes that a landing at St. Margarets Bay, then an undeveloped bay near Halifax, would be superior to a direct assault via the longer overland route.

- Failing to take Halifax, the US could occupy New Brunswick by land to cut Nova Scotia off from the rest of Canada at the key railway junction in Moncton.

- Quebec and the valley of the Saint Lawrence River:

- Occupying Montreal and Quebec City would cut the remainder of Canada off from the Eastern seaboard, preventing the movement of troops and resources in both directions.

- The routes from northern New York to Montreal and from Vermont to Quebec are both found satisfactory for an offensive, with Quebec being the more critical target.

- Ontario and the Great Lakes area:

- Occupying this region gains control of Toronto and most of Canada's industry and prevent Britain and Canada from using it for air or land attacks against the US industrial heartland in the Midwest.

- The plan proposes simultaneous offensives from Buffalo across the Niagara River, from Detroit across the Detroit River into Windsor, and from Sault Ste. Marie across the St. Mary's River into Sudbury. Controlling the Great Lakes for US transport is considered logistically necessary for a continued invasion.

- Winnipeg

- Winnipeg is a central nexus of the Canadian rail system for connecting the country.

- The plan saw no major obstacles to an offensive from Grand Forks, North Dakota, to Winnipeg.

- Vancouver and Victoria:

- Although Vancouver's distance from Europe reduces its importance, occupying it would deny Britain a naval base and cut Canada off from the Pacific Ocean.

- Vancouver could be easily attacked overland from Bellingham, Washington, and Vancouver Island could be attacked by sea from Port Angeles, Washington.

- The British Columbia port Prince Rupert has a rail connection to the rest of Canada, but a naval blockade is viewed as easy if Vancouver was taken.

No attacks outside Western Hemisphere first

Unlike the Rainbow Five plan, War Plan Red did not envision striking outside the Western Hemisphere first. Its authors saw conquering Canada as the best way to attack Britain and believed that doing so would cause London to negotiate for peace. A problem with the plan was that it did not discuss how to attack Britain if Canada declared its neutrality, which the authors believed was likely (the plan advised against accepting such a declaration without permission to occupy Canadian ports and some land until the war ended).[6] The U.S. decided it should focus on the North American and Atlantic theater of operations first while leaving its Pacific outposts of the Philippines, Guam, and American Samoa alone to fend off any British, Australian, and New Zealand attacks during the early stages of the conflict.[6]

Based on extensive war games conducted at the Naval War College, the plan rejected attacking British shipping or attempting to destroy the British fleet. The main American fleet would instead stay in the western North Atlantic to block British–Canadian traffic. The Navy would wait for a good opportunity to engage the British fleet and, if successful, would then attack British trade and colonies in the Western Hemisphere.[6]

In 1935, War Plan Red was updated and specified which roads to use in the invasion. "The best practicable route to Vancouver is via Route 99."[5]

American war planners had no thoughts of returning captured British territory: "The policy will be to prepare the provinces and territories of CRIMSON and RED to become U.S. state and territories of the BLUE union upon the declaration of peace." The planners feared that should they lose the war with Britain, America would be forced to relinquish its territories to the victors, such as losing Alaska to Canada as part of the peace treaty: "It is probable that, in case RED should be successful in the war, CRIMSON will demand that Alaska be awarded to her."[7][5]

British strategy for war against the United States

The British military never prepared a formal plan for war with the United States during the first half of the 20th century. For instance, the government of David Lloyd George in 1919 restricted the Royal Navy from building more ships to compete with American naval growth and thereby preventing the plan's development. Like their American counterparts, most British military officers viewed cooperation with the United States as the best way to maintain world peace due to the shared culture, language, and goals, although they feared that attempts to regulate trade during a war with another nation might force a war with America.[6]

The British military generally believed that if war did occur, they could transport troops to Canada if asked, but nonetheless saw it as impossible to defend Canada against the much larger United States, so did not plan to render aid, as Canada's loss would not be fatal to Britain. A full invasion of the United States was unrealistic and a naval blockade would be too slow. The Royal Navy could not use a defensive strategy of waiting for the American fleet to cross the Atlantic because Imperial trade would be left too vulnerable. Royal Navy officers believed that Britain was vulnerable to a supply blockade and that if a larger American fleet appeared near the British Isles, the Isles may quickly surrender. The officers planned to, instead, attack the American fleet from a Western Hemisphere base, likely Bermuda, while other ships based in Canada and the West Indies would attack American shipping and protect Imperial trade. The British would also bombard coastal bases and make small amphibious assaults. India and Australia would help capture Manila to prevent American attacks on British trade in Asia and perhaps a conquest of Hong Kong. The officers hoped that such acts would result in a stalemate making continued war unpopular in the United States, followed by a negotiated peace.[6]

Canadian military officer Lieutenant Colonel James "Buster" Sutherland Brown developed an earlier counterpart to War Plan Red, Defence Scheme No. 1, on April 12, 1921. Maintaining that the best defense was a good offense, "Buster" Brown planned for rapid deployment of flying columns to occupy Seattle, Great Falls, Minneapolis, and Albany. With little hope of holding the objectives, the actual idea was to divert American troops to the flanks and away from Canada, hopefully long enough for British and Commonwealth allies to arrive with reinforcements. Defense Scheme No. 1 was terminated by Chief of the General Staff Andrew McNaughton in 1928, two years before the approval of War Plan Red.

See also

- Trent Affair (1861)

- Pig War (1859)

- Aroostook War (1838–1839)

- War of 1812

References

- Roberts, Ken. Command Decisions. Center of Military History, Department of the Army. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- John Major, "War Plan Red: The American Plan for War with Britain," Historian (1998) 58#1 pp 12–15.

- June 15, 1939: Declassified Letter "Joint board to Secretary of Navy"

- Joint Estimate of the Situation – Red and Tentative Plan – Red (PDF). Security Classified Correspondence of the Joint Army-Navy Board, compiled 1918 – 03/1942, documenting the period 1910 – 3/1942. Joint Board, 325. Serial 274. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- Carlson, Peter (December 30, 2005). "Raiding the Icebox". Washington Post. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- Bell, Christopher M. (November 1997). "Thinking the Unthinkable: British and American Naval Strategies for an Anglo-American War, 1918-1931". The International History Review. 19 (4): 789–808. doi:10.1080/07075332.1997.9640804. JSTOR 40108144.

- Steven T. Ross, American War Plans, 1890-1939, 78, 145-152, 178, 180-181.

Further reading

- Bell, Christopher M., “Thinking the Unthinkable: British and American Naval Strategies for an Anglo-American War, 1918-1931”, International History Review, (November 1997) 19#4, 789–808.

- Holt, Thaddeus, "Joint Plan Red", in MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol. 1 no. 1.

- Major, John. "War Plan Red: The American Plan for War with Britain," Historian (1998) 58#1 pp 12–15.

- Preston, Richard A. The Defence of the Undefended Border: Planning for War in North America 1867–1939. Montreal and London: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1977.

- Rudmin, Floyd W. Bordering on Aggression: Evidence of U.S. Military Preparations Against Canada. (1993). Voyageur Publishing. ISBN 0-921842-09-0

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Rudmin, F. A 1935 US Plan for Invasion of Canada February 1995

- A Western Front Films Production in association with Brightside Films for Channel 5 America's Planned War On Britain: Revealed

- The Straight Dope Did the U.S. plan an invasion of Canada in the 1920s? February 2003