William Claiborne

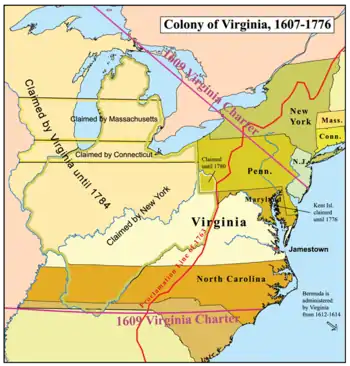

William Claiborne also, spelled Cleyburne (c. 1600 – c. 1677)[1] was an English pioneer, surveyor, and an early settler in the colonies/provinces of Virginia and Maryland and around the Chesapeake Bay. Claiborne became a wealthy planter, a trader, and a major figure in the politics of the colonies. He was a central figure in the disputes between the colonists of Virginia and the later settling of Maryland, partly because of his earlier trading post on Kent Island in the mid-way of the Chesapeake Bay, which provoked the first naval military battles in North American waters. Claiborne repeatedly attempted and failed to regain Kent Island from the Maryland Calverts, sometimes by force of arms, after its inclusion in the lands that were granted by a 1632 Royal Charter to the Calvert family. Kent Island had become Maryland territory after the surrounding lands were granted to Sir George Calvert, first Baron and Lord Baltimore (1579-1632) by the reigning King of England, Charles I (1600–1649; reigned from 1625 until his execution in 1649).

William Claiborne | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Secretary of State for the Virginia Colony | |

| In office 1626–1634 | |

| Parliamentary Commissioner and Secretary of the Virginia Colony | |

| In office 1648–1660 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1600 Crayford, Kent, Kingdom of England |

| Died | c. 1677 West Point, Virginia Colony, Kingdom of England |

| Occupation | surveyor, colonial government official, trader, planter |

Claiborne was an Anglican, a Puritan sympathizer, and deeply resentful of the Calverts' Catholicism. He was one of the signers, along with Virginia Governor John Pott, Samuel Matthews, and Roger Smyth, of a letter to the King's Privy Council, dated 30 November 1629, complaining that Lord Baltimore refused to take the Oath of Allegiance and Supremacy to the Church of England.[2] He sided with Parliament during the English Civil War of 1642–1651 and was appointed to a commission charged with subduing and managing the Province of Virginia and Province of Maryland, both British colonies at the time. He played a role in the submission of Virginia to parliamentary rule in this period. Following the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, he retired from involvement in the politics of the Virginia colony. He died around 1677 at his plantation, Romancoke, on Virginia's Pamunkey River. According to historian Robert Brenner, "William Claiborne may have been the most consistently influential politician in Virginia throughout the whole of the pre-Restoration period".[3]

Early life and emigration to America

Claiborne was born the county of Kent in England in 1600 to Thomas Clayborn, an alderman and lord mayor from King's Lynn, Norfolk, who made his living as a small-scale businessman involved in a variety of industries, including the salt and fish trades, and Sarah Smith, the daughter of a London brewer.[4] The family name was spelled alternately as Cleburn, Cleyborne, or Claiborne. William Claiborne, who was baptized in 1600, was the younger of two sons.[5] The family's business was not profitable enough to make it rich, and so Claiborne's older brother was apprenticed in London, becoming a merchant involved in hosiery and, eventually, the tobacco trade.[4]

However, Claiborne was offered a position as a land surveyor in the new colony of Virginia, and arrived at Jamestown, on the north shore of the James River in 1621. The position carried a 200-acre (80 hectare) land grant, a salary of £30 per year, and the promise of fees paid by settlers who needed to have their land grants surveyed. His political acumen quickly made him one of the most successful Virginia colonists, and within four years of his arrival he had secured grants for 1,100 acres (445 hectares) of land and a retroactive salary of £60 a year from the Virginia Colony's council. He also managed to survive the March 1622 attacks by native/Indian Powhatans on the Virginia settlers that killed more than 300 colonists. His financial success was followed by political success, and he gained appointment as Councilor in 1624 and Secretary of State for the Colony in 1626. Around 1627, he began to trade for furs with the native Susquehannock Indians from further north on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay and two of its largest tributaries, the Potomac and Susquehanna Rivers. To facilitate this trade, Claiborne wanted to establish a trading post on Kent Island in the mid-way of the Chesapeake Bay, which he intended to make the center of a vast mercantile empire along the Atlantic Coast.[4] Claiborne found both financial and political support for the Kent Island venture from London merchants Maurice Thomson, William Cloberry, John de la Barre, and Simon Turgis.[6]

Kent Island and the first dispute with Maryland

In 1629, George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore, arrived in Virginia, having traveled south from Avalon, his failed colony on Newfoundland. Calvert was not welcomed by the Virginians, both because his Catholicism offended them as Protestants, and because it was no secret that Calvert desired a charter for a portion of the land that the Virginians considered their own.[7] After a brief stay, Calvert returned to England to press for just such a charter, and Claiborne, in his capacity as Secretary of State of Virginia colony, was sent to England to argue the Virginians' case.[8] This happened to be to Claiborne's private advantage, as he was also trying to complete the arrangements for the trading post on Kent Island.

Calvert, a former high official in the government of King James I, asked the Privy Council for permission to build a colony, to be called Carolina, on land south of the Virginia settlements in area of the modern-day North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Claiborne arrived soon afterwards and expressed the concerns of Virginia that its territorial integrity was being threatened. He was joined in his protests by a group of London merchants who planned to build a sugar colony in the same area.[9] Claiborne, still intent on his own project, received a royal trading commission through one of his London supporters in 1631, one which granted him the right to trade with the natives on all lands in the mid-Atlantic where there was not already a patent in effect.[10]

Claiborne sailed for Kent Island on 28 May 1631 with indentured servants recruited in London and money for his trading post, likely believing Calvert's hopes defeated.[11] He was able to gain the support of the Virginia Council for his project and, as a reward for London merchant Maurice Thomson's financial support, helped Thomson and two associates get a contract from Virginia guaranteeing a monopoly on tobacco.[12] Claiborne's Kent Island settlers established a small plantation on the island and appointed a clergyman.[13] While the settlement on Kent Island was progressing, the Privy Council had proposed to Sir George Calvert, former Secretary of State for the King that he be granted a charter for lands north of the Virginia colony, in replacement for the unsuccessful settlements of his earlier colony of Avalon in Newfoundland (eastern modern Canada), in order to create pressure on the Dutch settlements further north along the Delaware and Hudson Rivers (modern states of Delaware, New Jersey and New York). Calvert accepted, though he died in 1632 before the charter could be formally signed by King Charles I, and the Royal Grant and Charter for the new colony of Maryland was instead granted to his son, Cecilius Calvert, on 20 June 1632.[14] This turn of events was unfortunate for Claiborne, since the Maryland charter included all lands on either side of the Chesapeake Bay north of the mouth of the Potomac River, a region which included Claiborne's proposed trading post on Kent Island, mid-way on the Bay. The Virginia Assembly, still in support of Claiborne and now including representatives of the Kent Island settlers, issued a series of proclamations and protests both before and after when the news of the granting of the Maryland charter reached across the ocean, claiming the lands for Virginia and protesting the charter's legality.[15]

Claiborne's first appeal to royal authority in the dispute, which complained both that the lands in the Maryland charter were not really unsettled, as the charter claimed, and that the charter gave so much power to Calvert that it undermined the rights of the settlers, was rejected by the Lords of Foreign Plantations in July 1633.[16] The following year, the main body of Calvert's settlers arrived in the Chesapeake and established a permanent settlement on Yaocomico lands at St. Mary's City.[17] With the support of the Virginia establishment, Claiborne made clear to Calvert that his allegiance was to Virginia and royal authority, and not to the proprietary authority in Maryland.[18] Some historical reports claim that Claiborne tried to incite the natives against the Maryland colonists by telling them that the settlers at St. Mary's were actually Spanish and enemies of the English, although this claim has never been proven.[19] In 1635, a Maryland commissioner named Thomas Cornwallis swept the Chesapeake for illegal traders and captured one of Claiborne's pinnaces in the Pocomoke Sound. Claiborne tried to recover it by force, but was defeated; although he retained his settlement on Kent Island. These were the first naval battles in North American waters, on 23 April and 10 May 1635; three Virginians were killed.[20]

During these events, Governor John Harvey of Virginia, who had never been well liked by the Virginian colonists, had followed royal orders to support the Maryland settlement and, just before the naval battles in the Chesapeake, removed Claiborne from office as Secretary of State.[21] In response, Claiborne's supporters in the Virginia Assembly expelled Harvey from the colony.[22] Two years later, an attorney for Cloberry and Company, who were concerned that the revenues they were receiving from fur trading had not recouped their original investment, arrived on Kent Island. The attorney took possession of the island and bade Claiborne return to England, where Cloberry and Company filed suit against him. The attorney then invited Maryland to take over the island by force, which it did in December 1637. By March 1638 the Maryland Assembly had declared that all of Claiborne's property within the colony now belonged to the proprietor.[23] Maryland temporarily won the legal battle for Kent Island and won again when Claiborne's final appeal was rejected by the Privy Council in April 1638.[24]

Parliamentary Commissioner and the second dispute with Maryland

In May 1638, fresh from his defeat over Kent Island, Claiborne received a commission from the Providence Land Company, who were advised by his old friend Maurice Thomson, to create a new colony on Ruatan Island off the coast of Honduras in the Caribbean Sea. At the time, Honduras itself was a part of Spain's Kingdom of Guatemala, and Spanish settlements dominated the mainland of Central America. Claiborne optimistically called his new colony Rich Island, but Spanish power in the area was too strong and the colony was destroyed in 1642.[25]

Soon after, the chaos of the English Civil War gave Claiborne another opportunity to reclaim Kent Island. The Calverts, who had received such constant support from the King, in turn supported the monarchy during the early stages of the parliamentary crisis. Claiborne found a new ally in Richard Ingle, a pro-Parliament Puritan merchant whose ships had been seized by the Catholic authorities in Maryland in response to a royal decree against Parliament. Claiborne and Ingle saw an opportunity for revenge using the Parliamentary dispute as political cover, and in 1644 Claiborne seized Kent Island while Ingle took over St. Mary's.[26] Both used religion as a tool to gain popular support, arguing that the Catholic Calverts could not be trusted. By 1646, however, Governor Leonard Calvert had retaken both St. Mary's and Kent Island with support from Governor Berkeley of Virginia, and, after Leonard Calvert died in 1648, Cecil Calvert appointed a pro-Parliament Protestant to take over as governor.[27] The rebellion and its religious overtones was one of the factors that led to passage of the landmark Maryland Toleration Act of 1649, which declared religious tolerance for Catholics and Protestants in Maryland.[28]

In 1648 a group of merchants in London applied to Parliament for revocation of the Maryland charter from the Calverts.[29] This was rejected, but Claiborne received a final opportunity to reclaim Kent Island when he was appointed by the Puritan-controlled Parliament to a commission which was charged with suppressing Anglican disquiet in Virginia; Virginia in this case defined as "all the plantations in the Bay of the Chesapeake."[30] Claiborne and fellow commissioner Richard Bennett secured the peaceful submission of Virginia to Parliamentary rule, and the new Virginia Assembly appointed Claiborne as Secretary of the colony.[31] It also proposed to Parliament new acts which would give Virginia more autonomy from England, which would benefit Claiborne as he pressed his claims on Kent Island. He and Bennett then turned their attention to Maryland and, arguing again that the Catholic Calverts could not be trusted and that the charter gave the Calverts too much power, demanded that the colony submit to the Commonwealth.[31] Governor Stone briefly refused but gave in to Claiborne and the Commission, and submitted Maryland to Parliamentary rule.[32]

Claiborne made no overt legal attempts to re-assert control over Kent Island during the commission's rule of Maryland, although a treaty concluded during that time with the Susquehannocks claimed that Claiborne owned both Kent and Palmer Islands.[33] Claiborne's legal designs on Maryland were once again defeated when Oliver Cromwell returned Calvert to power in 1653, after the Rump Parliament ended.[34] In 1654, Governor Stone of Maryland tried to reclaim authority for the proprietor and declared that Claiborne's property and his life could be taken at the Governor's pleasure.[35] Stone's declaration was ignored and Claiborne and Bennett again overthrew him, creating a new assembly in which Catholics were not allowed to serve.[36] Calvert, now angry at Stone for what he perceived as weakness, demanded that Stone do something, and in 1655 Stone reclaimed control in St. Mary's and led a group of soldiers to Providence (modern Annapolis). Stone was captured and his force defeated by local Puritan settlers, who took control of the colony.[37] Given the new situation, Claiborne and Bennett went to England in hopes of convincing Cromwell to change his mind but, to their dismay, no decision was made and, lacking royal authority, the Puritans gave power over to a new governor appointed by Calvert.[38] Going behind Claiborne's back, Bennett and another commissioner reached an agreement with Calvert that virtually guaranteed his continued control over Maryland through the remainder of the Protectorate.[39]

With no authority left in Maryland, Claiborne turned to his political offices in Virginia. However, as a consequence of his continuous conflict and disruption, over several years, of authority and government in both Maryland and Virginia in pursuit of his commercial interests, as well as his alliance with the Parliament faction during these activities, upon the restoration of the British monarchy in 1660 he had few friends left in government. Claiborne therefore retired from political affairs in 1660 and spent the remainder of his life managing his 5,000 acre (2,023 hectare) estate, "Romancoke", near West Point on the Pamunkey River, dying there in about 1677.[40]

Family life and descendants

In the midst of the political turmoil of the conflict over Kent Island, Claiborne married Elizabeth Butler of Essex, who would remain his wife at least through 1668.[5] Claiborne was also the forebear of a number of lines of American Claibornes, and among his descendants are William C. C. Claiborne, first governor of Louisiana, fashion designer Liz Claiborne,[41] the late minister Jerry Falwell, Folk musician/science and linguistics writer Robert Claiborne, and a number of political figures from Tennessee and Virginia.[42] Descendants of the Claiborne family have formed a society to advance the genealogical study of Claiborne's lineage.[43]

References

- A number of different sources dispute Claiborne's date of birth and which family he descended from in England, though Brenner, which is the most recent authoritative historical text, cites 1587 as the date of birth and the Norfolk/Kent Clayborns of England as his ancestors. Dates and other biographical information in this article are drawn from "Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography" 1887–89.

- Neill, Edward D. (1876). The founders of Maryland as portrayed in manuscripts, provincial records and early documents. Albany, NY: J. Munsell, 1876. p. 45.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brenner, p. 120

- Brenner, p. 121

- Richardson, p. 95

- Brenner, pp. 122–124

- Browne, p. 27 and Fiske, pp. 263–264

- Browne, p. 28 and Krugler, p. 107

- Fiske, p. 265

- Brenner, p. 124

- Brenner, p. 124 and Hatfield, p. 186

- Brenner, p. 131

- Fiske, p. 271

- Brenner, p. 141

- Brenner, pp. 141–142

- Browne, pp. 43–44

- Fiske, pp. 272–274

- Fiske, p. 274

- Osgood, p. 94 and Fiske, p. 275

- Hatfield, p. 186

- Fiske, p. 277

- Hatfield, p. 186 and Brenner, p. 143

- Osgood, p. 95 and Fiske, pp. 280–282

- Brenner, p. 157 and Fiske, pp. 281–282

- Brenner, p. 157

- Brenner, p. 167

- Osgood, pp. 113–114

- Fiske, pp. 288–290

- Brenner, pp. 167–168

- Osgood, pp. 120–121

- Osgood, p. 124

- Fiske, pp. 294–295

- Osgood, p. 127 and Fiske, p. 294

- Osgood, p. 121

- Osgood, p. 129

- Osgood, p. 130

- Osgood, p. 131

- Osgood, pp. 132–133

- Osgood, p. 133

- Fiske, p. 297

- Bernstein, Adam (2007-06-27). "Liz Claiborne, 78, Fashion Industry Icon". The Washington Post. pp. B07. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- . A number of genealogies reference his descendants, including Boddie's 1999 Virginia Historical Genealogies.

- "The National Society of the Claiborne Family Descendants". Retrieved 2008-01-22.

References

- Brenner, Robert (2003). Merchants and Revolution: Commercial Change, Political Conflict, and London's Overseas Traders. London:Verso. ISBN 1-85984-333-6.

- Browne, William Hand (1890). George Calvert and Cecilius Calvert: Barons Baltimore of Baltimore. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company.

- Fiske, John (1897). Old Virginia and Her Neighbors. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Krugler, John D. (2004). English and Catholic: the Lords Baltimore in the Seventeenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7963-9.

- Hatfield, April Lee (2004). Atlantic Virginia: Intercolonial Relations in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3757-9.

- Osgood, Herbert Levi (1907). The American Colonies in the Seventeenth Century. London: MacMilland and Company.

- Richardson, Douglas (2005). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8063-1759-0.