William FitzWilliam, 1st Earl of Southampton

William FitzWilliam, 1st Earl of Southampton, KG (c.1490, Aldwark, North Riding of Yorkshire – 15 October 1542, Newcastle upon Tyne), English courtier and soldier, was the third son of Sir Thomas FitzWilliam of Aldwark and Lady Lucy Neville, daughter of John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu.

The Earl of Southampton | |

|---|---|

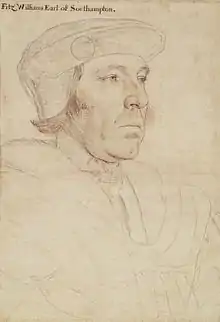

Portrait of William Fitzwilliam, Earl of Southampton, by Hans Holbein the Younger | |

| Treasurer of the Household | |

| In office 1525–1537 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Thomas Boleyn |

| Succeeded by | Sir William Paulet |

| Personal details | |

| Spouse(s) | Mabel Clifford |

| Mother | Lady Lucy Neville |

| Father | Sir Thomas FitzWilliam |

FitzWilliam's father died when he was in his infancy, and his mother remarried Sir Anthony Browne Sr. so that FitzWilliam was half-brother to Sir Anthony Browne Jr.. Probably as a result of this connection, he was chosen as a companion for Henry Tudor, Prince of Wales (later King Henry VIII of England) and brought up alongside him. After King Henry's coronation in 1509, he was made a Gentleman Usher and King's Cupbearer, and gradually rose at Court. He began his military career at sea, serving under the Marquess of Dorset in 1512, and Sir Edward Howard in the disastrous second attack on Brest. Unlike his commander, he escaped the debacle, but was badly injured by a crossbow bolt. He recovered sufficiently in time to accompany King Henry VIII into France as an Esquire of the Body, and was knighted on 25 September 1513, the day after the capture of Tournai. In November, he married Mabel Clifford, daughter of Henry Clifford, 10th Baron de Clifford, but the marriage would prove childless.

William FitzWilliam achieved distinction as naval commander, as diplomat, and as government minister. Much of his time as Vice-Admiral (1513–1525) and Admiral were spent keeping the English Channel free from pirates, and he gained praise from Cardinal Wolsey for his initiative in actions against the French. In May 1522, England declared war on France. The Earl of Surrey planned to attack Havre de Grace in June and Morlaix on 1 July, which largely failed due to practical difficulties. Fitzwilliam was appointed as Vice-Admiral, so when the Earl of Surrey abandoned the siege of Brest, he was left on station to blockade the port. The English navy patrolled the coast of Brittany for the next three months, but was unable to score a decisive victory with their Spanish allies. During the autumn, the sea patrol campaign was abandoned with little achieved.[1]

As ambassador at the French court around 1521, FitzWilliam attracted favorable notice from Cardinal Wolsey, showing suitability for higher office. Nonetheless, later missions failed: King Henry's obsession with his divorce from his wife, Queen Catherine of Aragon, gave his ambassadors little scope for any other initiative.

William Fitzwilliam was appointed Treasurer of the Household in 1525, a post which gave him an ex officio seat on the evolving Privy council. He was appointed Captain of Guines in 1524 and maintained a connection with Calais for the rest of his life, being largely responsible for the Calais Act of 1536; he also played a significant part in defusing religious unrest in Calais in the later 1530s. He served as a member of parliament for Surrey from 1529 until his elevation to the peerage as Earl of Southampton in 1537.[2]

FitzWilliam acted as "enforcer" for King Henry VIII in the fall of the King's wives, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, the Pilgrimage of Grace, and the Exeter Conspiracy. In 1539, as Admiral, he conveyed King Henry's future fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, from Calais, and on first meeting her, wrote letters in her praise to the King, 'considering it was then no time to dispraise her, ... the matter being so far passed.'[3]

In Autumn 1538 William and the Bishop of Ely went to question Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury. William then went onto hold Margaret Pole as his prisoner until May 1539.

From 1540, William FitzWilliam was a capable Lord Privy Seal until his death in 1542, but he failed to address serious structural faults at the Duchy of Lancaster and the Admiralty administration, probably because with several offices he was overworked – a serious fault in the Tudor system. As regional magnate, he eliminated factional strife in Surrey. The Earl of Southampton was appointed Lieutenant and Captain-General in the North in 1542, to command an expedition to Scotland, but he was a sick man who had to be conveyed to Newcastle upon Tyne in a litter. Nevertheless, he died in October only three days after his arrival there. FitzWilliam was apparently buried in Newcastle, for although under his will, a chapel was to be built for his tomb at the parish church in Midhurst, Sussex, no tomb was erected there. Having no legitimate issue, his peerage became extinct.[2] Upon his death, Cowdray House, originally purchased by FitzWilliam from Sir Henry Owen in 1529, was inherited by his younger half-brother, Sir Anthony Browne.

Notes

References

- Dollinger, German Hansa, pp.303–4; Lloyd, England and the German Hanse, pp.180–2; Rodger, Safeguard, p.174

- Johnson, S.R., History of Parliament online articleCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strype, John, Ecclesiastical Memorials, vol. 1 part 2, Oxford (1822), 454, deposition of Southampton.

Bibliography

- Castelli, Jorge H., Tudorplace biographyCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rodger, N.A.M. (1997). The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain. vol.1 660–1649. London: HarperCollins.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Thomas Boleyn |

Treasurer of the Household 1525–1537 |

Succeeded by Sir William Paulet |

| Preceded by Sir Thomas More |

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster 1529–1533 |

Succeeded by Sir John Gage |

| Preceded by The Duke of Richmond and Somerset |

Lord Admiral 1536–1540 |

Succeeded by The Lord Russell |

| Preceded by Thomas Cromwell |

Lord Privy Seal 1540–1542 | |

| Peerage of England | ||

| New creation | Earl of Southampton 1537–1542 |

Extinct |