Xiaoze Xie

Xiaoze Xie (Chinese: 谢晓泽; born 1966 in Guangdong, China) is a Chinese-American visual artist and professor based in Stanford, California.[1][2] His work includes painting, drawing, photography, installation and video, the best-known of which are his monumental paintings of library books and newspapers, which explore the ephemeral nature of time, history and cultural memory.[3][4][5] San Francisco Chronicle critic Kenneth Baker described Xie's approach as pairing "relaxed photorealism" with "conceptual tautness;"[6] others describe it as a "hybrid-like, postmodern blend" of traditional painting, Social Realism and contemporary documentary photography "laced with a decisively political undertone."[7] Xie has had solo exhibitions at galleries throughout the world,[8][9] and at institutions including the Asia Society Museum (New York),[10] Denver Art Museum,[11] Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art,[12] Knoxville Museum of Art (survey, 2011),[13] and Modern Chinese Art Foundation (Ghent, Belgium).[14] He has received awards from the Joan Mitchell Foundation and Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and his work belongs to the public art collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston,[15] Denver Art Museum,[16] Oakland Museum of California, and San Jose Museum of Art,[17] among others.[18][2] Xie is currently the Paul L. & Phyllis Wattis Professor of Art at Stanford University.[2]

Xiaoze Xie 谢晓泽 | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1966 |

| Education | Tsinghua University, Central Academy of Arts and Design, University of North Texas |

| Known for | Painting and drawing, Installation art, Video art, Photography |

| Awards | Joan Mitchell Foundation, Pollock-Krasner Foundation |

| Website | Xiaoze Xie |

Life and career

Xie was born in Guangdong Province, China in 1966.[19] After developing an interest in art as child, and in science and technology in high school, he chose to study architecture as a compromise, earning a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Tsinghua University in Beijing (1988).[19][20] A desire for a freer, less compromising career, however, compelled him to change to art.[20][21][13] He enrolled at Central Academy of Arts and Design in Beijing, where he received a master's degree (1991) and honed a realistic style inflected by modernism.[1][20]

Like many Chinese students in the 1980s, Xie became interested in Western ideas.[1] In 1991, his wife, Daxue Xu, received a scholarship to study physics at the University of North Texas, prompting a move to Denton, Texas.[20][21] Xie enrolled in the art department there the next year (MFA, 1996), where he encountered postmodernism, inspiring him to combine his realist skills with contemporary ideas and issues.[20] While in graduate school, he responded to his new American surroundings, painting scenes of junkyards, abandoned cars, and colorful, grocery-store abundance; he also initiated his soon-to-be signature "Library" works.[20][21]

In 1999, Xie began teaching at Bucknell University, while also pursuing exhibitions throughout the United States and in China; solo shows at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (2000) and Charles Cowles Gallery (New York, 2002, 2004) soon followed, bringing him his first major critical attention.[22][12][1][3][23] He has since had solo exhibitions at Chambers Fine Art (New York/Beijing), Anglim Gilbert Gallery (San Francisco), Nicholas Metivier Gallery (Toronto), Zolla/Lieberman (Chicago), Moatti Masters/Contemporary (London) and Gaain Gallery, (Seoul, Korea), among other venues.[24][25][21][26] Xie taught at Bucknell until 2009, serving as Chair of the Department of Art & Art History from 2007–9. In 2009, he accepted a position at Stanford University, where he continues to teach.[2]

Work and reception

Xie's art spans diverse media, but is unified by career-long themes of the library, books and newspapers, through which he explores time, historical memory, and the role of media in perceptions of the world.[20][27][28] Critics note in his work a balance between formal concerns, beauty and expressiveness on one hand, and on the other, conceptual rigor that addresses contemporary issues such as war, violence, power, human tragedy, and the construction of cultural knowledge.[29][6][30]

"Library" paintings

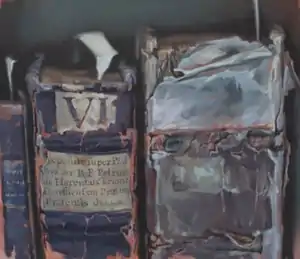

In 1993, Xie began painting library books, intrigued by the architectural quality of rows and stacks and by their conceptual potential as material carriers of ideology, cultural memory and history.[31][32] He has explored this theme in many forms (decaying Chinese manuscripts, venerable reference books, crisp art archives, musical scores) found in libraries and museums from around the world.[31][20][26][8][33] The "Library" paintings take up concepts including order and control (through systems of classification), the potential for disorder, decay, and the vulnerability and fragmentary nature of historical memory; Xie has suggested that his horror at the historical destruction of books by China's Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution, in part, played a role in his chosen themes.[20][21][33]

Xie's labor-intensive "Library" paintings[34] depict shelved books in large-scale close-up, revealing wear, human touch, and how objects are left.[31][26][20] He paints in what critics describe as a soft, brushy, almost impressionistic manner that captures the play of ethereal light, texture (crinkled parchment, frayed leather edges, pockmarks) and shadow;[26][4][35][36] his technique achieves precision but at times dissolves into near-abstraction or blurring that suggests a camera lens or the haze of memory.[37][21][35] Xie is sometimes linked to the realist and still-life traditions, but critics note several key differences: rather than stage tableaux, he photographs reference scenes as he finds them, composing in the viewfinder; he uses color subjectively, working in analytical near-black-and-white, warm red-brown-yellow, or almost-toxic greenish tones depending on his conceptual goals; he paints at a larger-than-life scale in which architectural presence de-familiarizes his subjects.[20][21][31][32] Kenneth Baker notes an interpretive openness in the work that can be read as elegiac, memorializing, cautionary, or critical, which is also foreign to traditional still life.[25][38]

"Newspaper" paintings

In the late 1990s, Xie expanded his oeuvre, painting library stacks of consecutive, folded newspapers that critic Roberta Smith described as a "conceptually based way of measuring time and history."[30][31][6] In the aftermath of 9/11, the work took on greater urgency as Xie chose eventful periods—the U.S. during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, China during the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and the Beijing Olympics—to more sharply comment on world events.[39][1][3][4] Writers suggest that the "Newspaper" paintings capture the chaotic, fleeting nature of the periodical—the immediacy and urgency of events upon publication and their quiet aftermath as yesterday's news,[27] as well as their relentless (often numbing) accumulation of information in an age of media saturation.[1][3][38][18]

_2008.jpg.webp)

Painted in the manner of the "Library" works, the "Newspaper" works range from monochromatic images of nearly-abstract horizontal patterning (e.g., "The Silent Flow of Daily Life" series)[40] to colorful, collage-like bands of images and text that collapse slivers of distinct events into surreal, ad hoc narratives about war, tragedy, power and national identity ("Fragmentary Views"[41] series).[1][3][23][42] The New York Times wrote of works such as March–April 2003, P.P-G. or March–April 2003, L.T.: "shards of war are laid on top of one another: guns, soldiers, a fireball and a plume of black smoke rolling over a row of palm trees. The staccato burst of images gives the painting a kind of jazzy rhythm."[1]

Xie has created several offshoots of the "Newspaper" works. His largely black-and-white "Theater of Power" (2006–8) series[43] draws on news photographs to depict Chinese leaders and moments during the Bush administration in brushy ink-on-rice-paper and oil works that reflect on causes and effects and the staging of news events (e.g., November 5, 2004. N.Y.T. (Bush Cabinet 2nd term)).[30][7] The "Both Sides Now" series (2007–15)[44] conveys the complexity and confusion of media overload through opened-up newspapers with overlapping, layered text and images that seem to have bled through from the back onto the front.[20][5][18] Xie's "Weibo" series (2013) extends his interest in ephemeral media with paintings of images downloaded from the popular Chinese social platform, many of them censored shortly after being posted.[5][32][45]

Installation, photographic and video works

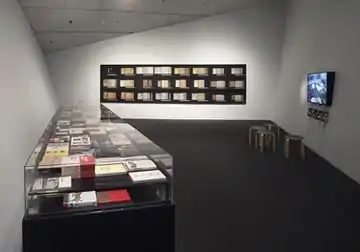

Xie's work in other media share the conceptual preoccupations of his paintings.[20][46] Several early installations (1994–9) addressed historical events involving censorship—the 20th-century student movements in China, the burning of books by the Nazis, the destruction of books by China's Red Guards.[20][47] He returned to that theme in the installation Rhythm of Time, Corridor of Memory (2010) and in the Denver Art Museum (DAM) and Asia Society shows, "Eyes On: Xiaoze Xie" (2017) and "Objects of Evidence" (2019).[11][48] The two shows investigated the history of book banning in China, revealing its ideological shifts by highlighting what different regimes made invisible.[36][48] They featured paintings, an installation of glass cases holding nearly three hundred banned books that Xie collected (Objects of Evidence, which compared first and second editions for censorship), life-size, mug-shot-like photographs of yellowing premodern books, and a documentary of Xie's research, Tracing Forbidden Memories.[36][11][10] Critic Barbara Pollack described the latter show's effect as "a mournful combination of awe and sadness."[48]

In several works, Xie used newspapers as a metaphor for temporality and the transitory nature of life, events and cultural memory. The video October–December 2001 (2002) shows a New York subway train of riders reading papers saturated with post-9/11 headlines (e.g., "Bloodbath," "Death Rattle"), set to a soundtrack of screeching trains and rapid-fire bongo music; it eventually empties leaving only the discarded dailies, in silence.[27][49] In the collaborative photographic/public intervention Last Days (2009, with Chen Zhong), he mounted newspaper on outside walls to create temporary monument/ruins throughout the Chinese city of Kaixian, which was razed, flooded and rebuilt on a different site as part of the Three Gorges Dam project.[20] Transience (2011) is a slow-motion color video showing ancient Chinese tomes and books by modernist thinkers in several languages floating against a depthless black ground as if tossed into the air; a warm glow from beneath suggests fire, the history of book burning, and the perishability of knowledge.[50][49]

Collections and recognition

Xie's work belongs to the public art collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston,[15] Denver Art Museum,[16] Oakland Museum of California, Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, Boise Art Museum, JPMorgan Chase Art Collection, Microsoft Art Collection,[51] San Jose Museum of Art,[17] and Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, among others.[18] He has received awards and grants from the Joan Mitchell Foundation (2013), Brooklyn Historical Society (2008), Pollock-Krasner Foundation (2003), Phoenix Art Museum (1999) and Dallas Museum of Art (1996), and a commission from the U.S. General Services Administration's Art-in-Architecture Program (2002).[2][31][52] Xie has also been recognized with an artist-in-residencies at the Dunhuang Academy (2017, the inaugural residency) and Arcadia in Mount Desert Island (2012), which inspired a new body of work focusing on the history and content of the ancient Mogao Caves.[46]

References

- Loos, Ted. "Fish Wrap, Bird Cage Liner, Still Life," The New York Times, March 21, 2004, p. 32. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Stanford University Department of Art & Art History. "Xiaoze Xie," People. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Nichols, Matthew Guy. "Xiaoze Xie at Charles Cowles," Art in America, June/July 2004, p. 181.

- Morse, Trent. "Xiaoze Xie at Chambers Fine Art," ARTnews, June 2011, p. 109.

- Wei, Lilly. "Xie Xiaoze at Chambers Fine Art," ARTnews, December 2013, p. 107.

- Baker, Kenneth. "Xie at Anglim," San Francisco Chronicle, June 23, 2012. p. E2. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Brumer, Andy. "Previews of Exhibitions: Xie Xiaoze," ArtScene, November 2008, p. 15–16. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Moatti Masters/Contemporary. Xiaoze Xie – Libraries (catalogue), London: Moatti Masters/Contemporary, 2015,

- Gaain Gallery. Xiaoze Xie: Legacy (catalogue), Seoul, Korea: Gaain Gallery, 2007,

- Holmes, Jessica. "Challenging Censorship, One Meticulous Artwork at a Time," Hyperallergic, November 21, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- Denver Art Museum. "Eyes On: Xiaoze Xie," Exhibitions. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Hopkins, Debra L. "Order: An Installation and Paintings by Xiaoze Xie," curator’s essay, Scottsdale, AZ: Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, 2000.

- Knoxville Museum of Art. "Knoxville Museum of Art Presents Xiaoze Xie – Amplified Moments," Exhibition materials, 2011.

- Doom, R. "Wanneer de dappere winterpruimen in de sneeuw bloesemen...," Xiaoze Xie: Werken op papier (catalogue), Ghent, Belgium: Modern Chinese Art Foundation, 2006.

- The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. "Xiaoze Xie, Gold No. 8," Collections. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Denver Art Museum. Through Fire (Books that Survived the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance at Tsinghua University, No.1), 2017, Collections. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- San Jose Museum of Art. "Immigrant Heritage Month: Initial Public Offering: New Works from SJMA’s Collection," Events. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Li, Na. "Exhibit shows transient nature of news and life," China Daily (Canada), June 5, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Smithsonian Archives of American Art. "Oral history interview with Xiaoze Xie, 2010 May 10–11." Collections. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Claypool, Lisa. "China Urban: An Interview with Xie Xiaoze," Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, July/August 2009, p. 41-50.

- Dault, Gary Michael. "To Paint Book Is to Save Them," The Globe and Mail, September 12, 2009.

- Updike, Robin. "Show Wrestles with Reality, Books Dominate Xie’s Haunting, Ambiguous Work," Seattle Times, February 25, 1999.

- The New Yorker. Review and reproduction, The New Yorker, April 5, 2004. p.14, 18.

- Chambers Fine Art. "Xie Xiaoze," Artists. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Baker, Kenneth. "Library Still Lifes Exude Elegiac Air," San Francisco Chronicle, January 9, 2010. p. E3. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Artner, Alan G. Review, Chicago Tribune, May 7, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Schnoor, Christopher. "The News in Art at Boise Art Museum," Boise Weekly, February 22–28, 2006, p. 11–13.

- New American Painting. New American Painting (Pacific Coast), December/January 2013, p. 150-153. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Heartney, Eleanor. "A War and Its Images," Art in America, October 2004, p. 55.

- Smith, Roberta. "When Newspaper Photographs Are Worth a Thousand Paintings," The New York Times, November 6, 2008. p. C1, C5. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Vaughn, Katie. "Speaking Volumes," Quad-City Times, February 11, 2007, Section H, p. 1, 7. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Memarian, Omid. "Confrontation and Disruption in a New Exhibition by Chinese-American Artist Xiaoze Xie," Global Voices, April 11, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Amer, Aïda. "Xiaoze Xie," Endurance: New Works by Xiaoze Xie, Beijing/New York: Chambers Fine Art, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Xiaoze Xie. "Library,". Works. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Epstein, Edward M. "Close Reading: Xie Xiaoze paints blown-up books," artcritical, May 29, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Boyd, Kealey. "How Books Get Banned," Hyperallergic, February 15, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Muchnic, Suzanne. "Old Meets Bold," Los Angeles Times, March 20, 2005. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Boyle, Kathleen. "Xiaoze Xie: Read All About It, Enduring Ephemera," Hyperallergic, February 15, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Heartney, Eleanor. "The Certainty of Uncertainty: History and Memory in the Work of Xiaoze Xie" (Catalogue essay), Xiaoze Xie: 2001-2003 Fragmentary Views, New York: Charles Cowles Gallery, 2004.

- Xiaoze Xie. "The Silent Flow of Daily Life,". Works. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Xiaoze Xie. "Fragmentary Views,". Works. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Hawkins, Margaret. "Clever pieces show that by the word, it's still art," Chicago Sun-Times, April 26, 2006, p. 45. Retrieved August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Xiaoze Xie. "Theater of Power,". Works. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Xiaoze Xie. "Both Sides Now,". Works. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Xiaoze Xie, "Weibo,". Works. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Zhang, Jessica. "Xiaoze Xie presents his Dunhuang artwork," The Stanford Daily, July 5, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Xiaoze Xie. "Installations,". Works. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Pollack, Barbara. "Xiaoze Xie: Objects of Evidence at Asia Society New York," CoBo Social, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- Xiaoze Xie. "Videos,". Works. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Baker, Kenneth. "Wilson-Ryckman and Xie," San Francisco Chronicle, September 7, 2013, p. E-2. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Nelson, Lisbet. "Emphasis Is on Innovative Art For Growing Microsoft Collection," ARTnews, April 25, 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Caine, William. "The Spirit of Law/Iowa Reports," GSA Art in Architecture Selected Artworks, 1997-2008, ("Introduction," Eleanor Heartney), U.S. General Services Administration, 2008, p.100–103.

External links

- Xiaoze Xie official website.

- Oral history interview with Xiaoze Xie, May 2010.

- Xiaoze Xie on The Modern Art Notes Podcast, No. 414

- Xiaoze Xie faculty page, Stanford university.

- "China Urban: An Interview with Xie Xiaoze," Lisa Claypool.

- Xie Xiaoze artist page, Chambers Fine Art.