Y'all

Y'all (pronounced /jɔːl/ yawl[2]) is a contraction of you and all, sometimes combined as you-all. Y'all is the main second-person plural pronoun in Southern American English, with which it is most frequently associated,[3] though it also appears in some other English varieties, including African-American English and South African Indian English. It is usually used as a plural second-person pronoun, but whether it is exclusively plural is a perennial subject of discussion.

Etymology

Y'all arose as a contraction of you all. The term first appeared in the Southern United States in the early nineteenth century,[4] though it was probably uncommon at that time, its usage not accelerating as a whole Southern regional phenomenon until the twentieth century.[5] The earliest attestation, with the spelling you all and in the specific second-person plural pronoun usage, is 1824.[6][7] Earliest attestations with the actual spelling y'all are from 1856,[8] however it was likely pronounced y'all much earlier. Another notable early attestation is in the Southern Literary Messenger (published in Richmond, Virginia) in April 1858.[9] It is not certain whether its use began specifically with black or white residents of the South;[4] one possibility is that the term was brought by Scots-Irish immigrants to the South, evolving from the earlier Ulster Scots term ye aw.[10][11][12] An alternative theory is that y'all is a calque of Gullah and Caribbean creole via earlier dialects of African-American English.[7] Most linguists agree that y'all is an original form, deriving from indigenous processes of grammar and morphological change, rather than being directly transferred from any other English dialects.[7]

Y'all appeared at different times in different dialects of English, including Southern American English and South African Indian English, indicating it is likely a parallel but independent (unrelated) development in those two dialects.[13] However, its emergence in both Southern and African-American Vernacular English indeed correlates in terms of the same basic time and place.

The spelling y'all is the most prevalent in print, being ten times as common as ya'll;[14] much less common spelling variants also exist, like yall, yawl, and yo-all.[4]

Linguistic characteristics

Functionally, the emergence of y'all can be traced to the merging of singular ("thou") and plural ("ye") second-person pronouns in Early Modern English.[7] Y'all thus fills in the gap created by the absence of a separate second-person plural pronoun in standard modern English. Y'all is unique in that the stressed form that it contracts (you-all) is converted to an unstressed form.[14]

The usage of y'all can satisfy several grammatical functions, including an associative plural, a collective pronoun, an institutional pronoun, and an indefinite pronoun.[10][15]

Y'all can in some instances serve as a "tone-setting device to express familiarity and solidarity."[16] When used in the singular, y'all can be used to convey a feeling of warmth towards the addressee.[17] In this way, singular usage of y'all differs from French, Russian or German, where plural forms can be used for formal singular instances.[17]

Singular usage

There is long-standing disagreement among both laymen and grammarians about whether y'all has primarily or exclusively plural reference.[7] The debate itself extends to the late nineteenth century, and has often been repeated since.[15] While many Southerners hold that y'all is only properly used as a plural pronoun, strong counter evidence suggests that the word is also used with a singular reference,[4][14][17][18] particularly amongst non-Southerners.[19]

H. L. Mencken recognized that y'all or you-all will usually have a plural reference, but acknowledged singular reference use has been observed. He stated that plural use

is a cardinal article of faith in the South. ... Nevertheless, it has been questioned very often, and with a considerable showing of evidence. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, to be sure, you-all indicates a plural, implicit if not explicit, and thus means, when addressed to a single person, 'you and your folks' or the like, but the hundredth time it is impossible to discover any such extension of meaning.

— H. L. Mencken, The American Language Supplement 2: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States, 1948, p.337[20]

Possessive forms

The existence of the genitive (or possessive) form y'all's indicates that y'all functions as a pronoun as opposed to a phrasal element.[16] The possessive form of y'all has not been standardized; numerous forms can be found, including y'alls, y'all's, y'alls's, you all's, your all's, and all of y'all's.[15]

All y'all

All y'all, all of y'all, and alls y'all are used by some speakers to indicate a larger group than is necessarily implied by simply y'all.[21] All y'all can also be used for emphasis; the existence of this etymologically pleonastic form is further evidence that speakers now perceive y'all as a grammatically indivisible unit.[15]

Regional usage

United States

Y'all has been called "perhaps the most distinctive of all grammatical characteristics" of Southern American English, as well as its most prominent characteristic.[7] People who move to the South from other regions often adopt the usage, even when other regional usages are not adopted.[23] Outside the southern United States, y'all is most closely associated with African-American Vernacular English.[24] African Americans took Southern usages with them during the twentieth-century exodus from the South to cities in the northeastern United States and other places within the nation. In urban African-American communities outside of the South, the usage of y'all is prominent.[25]

The use of y'all as the dominant second person-plural pronoun is not necessarily universal in the Southern United States. In the dialects of the Ozarks and Great Smoky Mountains, for example, it is more typical to hear you'uns (a contraction of "you ones") used instead.[15] Other forms have also been used increasingly in the South, including the use of you guys.[15]

Overall, the use of y'all has been increasing in the United States, both within and outside the southern United States. In 1996, 49% of non-Southerners reported using y'all or you-all in conversation, while 84% of Southerners reported usage, both percentages showing a 5% increase over the previous study, conducted in 1994.[15]

South Africa

In South Africa, y'all appears across all varieties of South African Indian English.[26] Its lexical similarity to the y'all of the United States is attributed to coincidence.[26]

Rest of world

Y'all is found, to greater or lesser degrees, in other dialects of English, including the dialects of St. Helena and Tristan da Cunha,[27] and Newfoundland and Labrador.[28] It is also found in Alberta, Cornwall, the Philippines, and extensively in New Zealand among Polynesians.

See also

| Look up y'all in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up all y'all in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

References

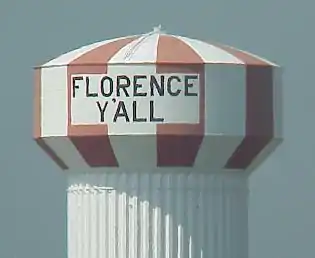

- "Water towers loom large". The Cincinnati Enquirer. April 7, 2001. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- you-all and y'all. Dictionary.com. Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary. 2019.

- Bernstein, Cynthia: "Grammatical Features of Southern speech: Yall, Might could, and fixin to". English in the Southern United States, 2003, pp. 106 Cambridge University Press

- Crystal, David. The Story of English in 100 Words. 2011. p. 190.

- Devlin, Thomas Moore (2019). "The Rise Of Y’all And The Quest For A Second-Person Plural Pronoun". Babbel. Lesson Nine GmbH.

- Harper, Douglas. "y'all". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Schneider, Edgar W. "The English dialect heritage of the southern United States", from Legacies of Colonial English, Raymond Hickey, ed. 2005. p.284.

- Parker, David B. (2015). "Y’all: It’s Older Than We Knew". History News Network.

- Parker, David B. "Y'All: Two Early Examples." American Speech 81.1 (2006): 110-112. .

- Montgomery, Michael. "British and Irish antecedents", from The Cambridge History of the English Language, Vol. 6, John Algeo, ed. 1992. p.149.

- Bernstein, Cynthia: "Grammatical Features of Southern Speech: Yall, Might could, and fixin to". English in the Southern United States, 2003, pp. 108-109 Cambridge University Press

- Lipski, John. 1993. "Y'all in American English," English World-Wide 14:23-56.

- Hickey, Raymond. A Dictionary of Varieties of English. 2013. p.231.

- Garner, Bryan. Garner's Modern American Usage. 2009. p.873.

- Bernstein, Cynthia. "Grammatical features of southern speech", from English in the Southern United States, Stephen J. Nagle, et al. eds. 2003. pp.107-109.

- Hickey, Raymond. "Rectifying a standard deficiency", from Diachronic Perspectives on Address Term Systems. Irma Taavitsainen, Andreas Juncker, eds. 2003. p.352.

- Lerner, Laurence. You Can't Say That! English Usage Today. 2010. p. 218.

- Hyman, Eric (2006). "The All of You-All". American Speech. 81 (3): 325–331. doi:10.1215/00031283-2006-022.

- Okrent, Anrika (2014-09-14). "Can Y'all Be Used to Refer to a Single Person?". The Week. The Week Publications. Retrieved 2014-09-15.

- Mencken, H.L. (4 April 2012). The American Language Supplement 2: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States. A. Knopf ebook. ISBN 9780307813442. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- Simpson, Teresa R. "How to Use "Y'all" Correctly".

- Dialect Survey Results

- Montgomery, Michael. "Y'all", from The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, Vol. 5: Language. Michael Montgomery et al. eds. 2007.

- Baugh, John. Beyond Ebonics. 2000. p.106

- Wright, Susan. "'Ah'm going for to give youse a story today': remarks on second person plural pronouns in Englishes", from Taming the Vernacular, Jenny Cheshire and Dieter Stein, Eds. Routledge, 2014. p.177.

- Mesthrie, Rajend. "South African Indian English", from Focus on South Africa. Vivian de Klerk, ed. 1996. pp.88-89.

- Schreier, Daniel. "St Helenian English", from The Lesser Known Varieties of English: An Introduction. Daniel Schreier, et al. eds. 2010. pp.235-237, 254.

- Clarke, Sandra. "Newfoundland and Labrador English", from The Lesser Known Varieties of English: An Introduction. Daniel Schreier, et al. eds. 2010. p.85.